The theories of strategy and competitive advantage described above have been helpful in focusing the attention of managers and researchers on strategic decisions. But have they enabled managers to improve their strategic viability? As Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad note, strategy, as it is currently practiced, may be a distraction from real strategic action.

As “strategy” has blossomed, the competitiveness of Western companies has withered. This may be coincidence, but we think not. We believe that the application of concepts such as “strategic fit” (between resources and opportunities), “generic strategies” (low cost vs.differentiation vs. focus), and the “strategy hierarchy” (goals, strategy, and tactics) have often abetted the process of competitive decline.29

Static models of strategy describe competition at one point in time. This is effective in an environment in which changes are slow and sustaining advantage is the goal. But in hypercompetition, where change is rapid and the goal is disruption, effective strategy has to have a more dynamic focus. Strategy requires a theory that pays attention to the sequential moves and countermoves of competitors over long periods of time. As competition has heated up, this dynamic interaction among competitors has become the key to competitive success. Success depends not on how the firm positions itself at a certain point in time, but on how it .acts over long periods of time. So the shift from static thinking to dynamic focus is crucial to understanding strategy in the long run.

Michael Porter recognized this need in a 1991 speech in which he noted, “The frontiers of the strategy field lie in integrative frameworks that address the dynamics of strategy choice over time, and which help us better understand the strategy/organization interface.”30

A dynamic view is based on three major principles. The first is that all actions are really interactions. This is examined below in the discussion of dynamic strategic interactions. The second principle is that all actions are relative. The value, risks, and effectiveness of every move must be seen in relation to the actions of competitors. The third is that competitors need to project out the long-term trends and trajectories of competitive maneuvers to see how they evolve and to understand where these actions lead. Simply looking at one or two interactions is not enough. These trajectories are examined later in this introduction.

1. Dynamic Strategic Interactions

In a basketball game a team’s performance is much more than a composite of the stats of individual players. It is how the players understand the game and react to the opposing team that determines their scoring ability. It is a rapid series of moves and countermoves that propel the game forward.

In the discussion of strategy in the following chapters, these moves and countermoves are labeled “dynamic strategic interactions.” In each dynamic strategic interaction one firm acts to gain a temporary advantage over its competitor. The competitor then responds to neutralize that advantage or to build a new advantage. The first company is forced to respond to this new action. Each interaction modifies the nature of competition between firms, often moving the industry to more intense levels of competition. Through these moves and countermoves companies attempt to disrupt the status quo in the industry to gain advantage.

The term interactions, as opposed to actions, is key to the understanding of strategy presented here. Economists have long recognized the interdependence of firms in oligopolies, industries with a small number of large players. Under such conditions the success of a strategy depends on how competitors interact. Economists, however, have overlooked the interdependency of firms in fragmented industries, those with a large number of small players. These firms are just as engaged in interactions in struggling over markets, niches, or even specific customers.

These are dynamic strategic interactions because, as mentioned above, these interactions evolve over long time frames. The organizations that survive and thrive over decades don’t remain static. They change their position in the marketplace and undertake new initiatives or change their strategic focus to outmaneuver the competition. They maintain a flexible posture that allows them to be dynamic.

No single play will work in all situations. Instead the team with resources that allow for flexible responses and a variety of moves over the course of the whole season will most likely win. Even the specific resources needed to achieve flexibility will change over time as firms compete to become more flexible than others. Thus, dynamic competitive advantage is not due to a single item. Winning results from many nonsustainable plays. Once used, each play loses its effectiveness because it becomes known to competitors, so winning depends on having a deep bench, the imagination to invent new plays, and the flexibility to be able to carry out those plays in an unpredictable way.

2. Strategy Is Relative

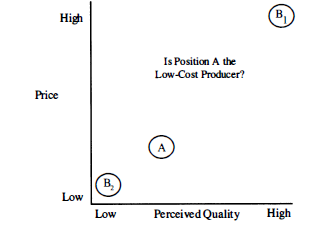

There are no absolutes in strategy. A company’s competitive position and the sustainability of its advantage are related to the moves of its competitors. For example, consider Figure 1-3. Is position A the low-cost producer? The answer depends on where competitors are positioned. If competitor B is positioned in the upper right (B1), the answer is yes. A offers the low-price-low-quality product, while B offers the premium product. If, on the other hand, the competitor is in position B2, the answer would be no. Here, A offers the premium-priced-high-quality product.

FIGUREI-3

STRATEGIC RELATIVISM

Moreover, A can become the low-cost producer without changing its strategy at all. Look what happens when B switches from position B2 to position B,. Without doing anything, firm A has now suffered a change in its strategic position. When Frank Perdue brought heavily advertised, premium-priced chickens into the poultry market, he transformed other branded chickens into low-cost producers. Without moving an inch, their relative position had been transformed.

This movement by competitors also affects the sustainability of a given strategy. Competitors’ moves determine whether a given high- or low-cost position will produce profits for a long or short period of time. If competitors do not act aggressively to respond to a company’s actions, then it can enjoy the competitive advantage it has gained. But if competitors act quickly to neutralize the company’s advantages, then it will also have to adjust its strategy to meet these new assaults. Suppose a firm is at B1 in Figure 1-3. It looks like a premium-priced-high-quality differentiator. However, if several firms move into that position, the initial firm is no longer differentiated, and its old differentiation advantage is lost because of the relative position of its competitors.

Relativity is important because a given price-quality strategy cannot be labeled as “low cost” or “differentiated” without knowing the positions of competitors. Once labeled, the strategy still may change because of changes in the actions of competitors or in the environment. A specific advantage cannot be labeled “sustainable” without considering whether competitors will allow the advantage to be sustained.

3. Trajectories in Four Arenas of Competition

The strategic position of a firm is not only relative to the position of competitors, it must also be taken in the context of the historical sequence of interactions undertaken by competitors. Each action is embedded in a series of actions that can affect counterresponses in ways that are unforeseen. So it is possible to win the battle and lose the war. For example, JFK may have won the Cuban missile crisis, but the long-run effect was to motivate the Soviets to undertake the most massive buildup of nuclear arms in their history, leading to nuclear parity with the United States by the early 1970s.

The same is true in business. The traditional doctrine for business strategy is that a firm should use its competitive advantage (its strength) to attack where the competitor lacks an advantage (its weakness). Hardly anyone would disagree with this piece of common sense. Using strength against weakness is the clearest way to gain superiority in a marketplace. Only a fool would attack the strength of a competitor. Only an even bigger fool would attack with his weakness.

This doctrine is, however, faulty if one considers the dynamics of strategic interaction. Consider a tennis match between two players with strong forehands and weak backhands. Player No. 1, following traditional strategy, uses his strength (forehand) to attack his opponent’s weakness (his backhand). This strategy appears to work brilliantly over the short term.

But consider what happens after two hundred volleys. Thanks to all the practice from player no. 1, player no. 2 has now improved his backhand. Player no. 1 suddenly is facing an opponent with a strong forehand and a strong backhand. At the same time player no. 1 has become very predictable; he will always play to his opponent’s backhand. The winning strategy for the short term ultimately results in disadvantage and loss in the long run.

Now consider what happens when an American consumer electronics company uses traditional doctrine against an opponent. Each has several hundred or even a thousand products, the equivalent of numerous volleys in a tennis match. The American company learns to apply its strength against weakness and is rewarded for it in the short run. But the opponent wins the war because he builds new competitive advantages as his weaknesses are tested and rectified. Thus, it is crucially important to track the volleys between firms. Otherwise, a firm will win the battle and lose the war.

As outlined above, traditional theories of strategy define four dimen-sions of competitive advantage for which firms compete. These dimen, sions provide a useful framework for tracking the dynamic strategic inter, actions among competitors over long periods of time and for understand, ing the evolution of industries. As mentioned above, these arenas are based on competition with respect to

- cost and quality

- timing and know,how

- strongholds

- deep pockets

Part I of this book will examine in detail how each of these sources of traditional competitive advantage play out over decades, based on two years of research on hundreds of industries and considerable anecdotal ev, idence from extensive case studies. This section describes common pat, terns of moves and countermoves as competitors struggle to gain control in each of these arenas. Below is a brief outline of the trends of these moves and countermoves in each arena.

THE TREND IN THE COST AND QUALITY ARENA

The first arena is competition based on cost and quality. Product position, ing can be a source of strategic advantage. Usually firms compete by offer, ing differing levels of quality at different prices because if they all offer the same,price and ,quality product, they will have created a commodity mar, ket. When quality is not a factor, firms are forced to engage in price wars because this is the only dimension in which they can compete. As hypercompetition escalates, firms use new dimensions of quality and ser, vice to differentiate themselves. Some firms try to cover all the ground between being a high,priced-high,quality differentiator and low,priced- low,quality cost leader by becoming fulUine producers. For example, General Motors offers products that range from Chevys to Cadillacs, and Microsoft makes DOS, Windows, and NT software.

But competitors still have room to join the industry at the high end or low end with niche or outflanking strategies. The competition often moves to these areas. Moves into the upper and lower segments of the market then raise the top of the market or lower the bottom of it. Firms also attempt to carve out specialty markets to fill holes in the middle. The fulUine competitor must respond by raising quality or lowering price. This tends to drive the costs down and quality up until the industry approaches the point of “ultimate value.” This is the optimal ratio of cost and quality that can be delivered by firms seeking to offer high-quality-low-priced goods. As all firms in the industry converge on this point, advantages become increasingly difficult to develop, because all firms have the same ratio of price and quality and the same product offerings. Thus, price war ironically reemerges after a series of hypercompetitive maneuvers are played out to avoid a price war among firms that initially offered very similar products.

When American restructured its fares for “value pricing” in April 1992, lowering coach fares by as much as 38 percent, it touched off a violent price war. A month later Northwest announced a two-for-one promotion, and American responded with a 50 percent cut in fares. On the quality side companies have offered new seating arrangements and improved amenities to set themselves apart from the competition. These advantages are, of course, quickly copied by competitors. Once the cost-quality advantage is eroded, the company must move on to the next one.

THE TREND IN THE TIMING AND KNOW-HOW ARENA

One way to escape this cycle of competition on price and quality is to enter a new market or launch a new product. Timing of market entry and the know-how that allows entry form the second arena for competitive interaction. A first mover can seize control of the market but often invests heavily in establishing a product or service that can be imitated and improved upon by competitors. To foil the imitators, the first mover may create impediments to imitation. But the followers then attempt to overcome these impediments. The followers become faster at imitation, forcing the first mover to change tactics. The first mover may then use a strategy of leapfrogging innovations, building on large technological advances that require entirely new resources and know-how. This makes it harder for an imitator to develop the same resources, but eventually the imitators do catch up. This forces the first mover to seek new leapfrog moves, which become more expensive and risky with each leap.

These cycles of innovation and imitation eventually lead to a market in which the last available leapfrog move is exploited and imitated and continuing the leapfrogging strategy becomes unsustainable because the cost of the next-generation leapfrog is too high. At this point, even if a new technological leapfrog jump can be made, it takes so long that competitors have time to catch up. In addition, when imitators become very fast at imitating, the first mover doesn’t have time to recapture its investment in R&D. Thus, as can be seen in the personal computer industry, technology-based first mover advantage still ends up converting what was once a market of many differentiated products into a market that is largely a price-competitive market.

Microsoft has introduced a series of new products, building on its knowhow. But the costs of development continue to rise. Windows cost one hundred million dollars, and analysts expected that Microsoft’s new database, Cirrus, could lose money for years because of its high costs of development.31 American Airlines’ innovations, even its computerized reservation system, have been copied by competitors. Some entrepreneurial travel agents have even reverse-engineered the data output by computer reservation systems to produce analyses of fare changes that benefit their corporate clients. This has eliminated American’s listing advantage and helps customers to defeat American’s efforts to manage its “yield,” forcing it to come up with new innovations to stay ahead of competitors.

THE TREND IN THE STRONGHOLDS ARENA

As the move toward ultimate value and rapid imitation tends to level the playing field, competitors seek to gain advantage by creating strongholds that exclude competitors from their turf. By creating entry barriers around a stronghold in a certain geographic region, industry, or product market segment, the firms try to insulate themselves from competitive attacks based on price and quality or innovation and imitation.

While firms build entry barriers that keep others out of their markets, this tactic is rarely sustainable over the long run. Entrants eventually find ways to circumvent entry barriers. After building a war chest in their own strongholds, competitors can fund forays into the protected strongholds of others. These expeditions usually provoke a response from the attacked companies. Such responses often go beyond defensive actions in the attacked market by leading to a counterattack against the initiating firm’s stronghold. These attacks and counterattacks often erode the strongholds of both players. This process can be seen on a large scale in globalized markets where huge businesses based on one continent attack the strongholds of large companies based on other continents until it becomes hard to tell whether competitors are American or Japanese (or any other nationality) anymore. As entry barriers have come down and markets integrate, the playing fields again begin to level out and the old competitive advantages provided by having a protected stronghold are no longer viable.

In launching its NT software, Microsoft is using the momentum of its stronghold in DOS operating systems to invade Novell’s stronghold of networking software. Competitors are countering with their own software. Each change in systems shakes up the market boundaries. For example, the launch of Windows allowed Microsoft to gain ground in spreadsheets from market leader Lotus. The battle to invade Microsoft’s core market has yet to begin, but the world has not yet seen how IBM and Apple will seek to regain the initiative from Microsoft ..

American Airlines has used its stronghold in the United States to move into European markets. From 1988 to 1992, it increased its overseas revenues from 12 percent to 26 percent.32 Although European governments have responded by trying to protect their national airlines, the European Community has begun long-haul deregulation. This promises to increase opportunities for American Airlines and other U.S. competitors. In re, sponse British Airways is seeking entry opportunities into the United States via acquisition. If this process continues, one global airline market will eventually emerge with only a few very large players dominating the trunk lines between continents.

THE TREND IN THE DEEP-POCKETS ARENA

After firms exhaust their advantages based on cost and quality, timing and know-how, and after their strongholds have fallen, they often rely upon their deep pockets. The fourth arena in which firms try to develop strategic advantage is based on financial resources. Well-endowed firms can use their brute force to bully a small competitor. These large firms have greater endurance, using their resources to wear down or undercut their opponents. But the small competitors are not completely defenseless. They can call upon government regulations, develop formal or informal alliances, or step aside to avoid competition with the deep-pocket firm. With these moves and countermoves, or even with the erosion of resources over time, the large firm eventually loses its deep,pocket advantage. When small firms build their access to resources through joint ventures or alliances, power tends to equalize and balance out, and large-scale global alliances of megacompetitors create the business equivalent of King Kong versus Godzilla. Eventually the deep-pocket advantage is neutralized.

American Airlines’ deep pockets have given it an advantage in price wars with competitors, but American’s size has also made it vulnerable because of the high operating costs associated with managing an older, more complex, and geographically dispersed fleet. Although much smaller than American, Southwest has a 43 percent cost advantage over its larger competitor, allowing it to continue to expand its services. Similarly, Microsoft’s deep pockets, built on the profits from DOS and Windows, have been used for research to build the next generation of software, but the alliance between IBM and Apple creates a very formidable deep pocket for funding the design of the next generation of software.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.