Buddhism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of the Buddha, Siddhārtha Gautama, who lived between approximately 563 and 483 BCE. Originating in India, Buddhism gradually spread throughout Asia to Central Asia, Tibet, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, as well as the East Asian countries of China, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan.

Buddhism teaches followers to perform good and wholesome actions, to avoid bad and harmful actions, and to purify and train the mind. The aim of these practices is to awaken the practitioner to the realization of true reality and the achievement of Nirvana.

Buddhist morality is underpinned by the principles of harmlessness and moderation. Mental training focuses on moral discipline (sila), meditative concentration (samadhi), and wisdom (prajñā).

While Buddhism does not deny the existence of supernatural beings (indeed, many are discussed in Buddhist scripture), it does not ascribe power for creation, salvation or judgement to them. Like humans, they are regarded as having the power to affect worldly events, and so some Buddhist schools associate with them via ritual.

Buddhism (/ˈbʊdɪzəm/, US: /ˈbuːd-/)[1][2] is an Indian religion based on a series of original teachings attributed to Gautama Buddha. It originated in ancient India as a Sramana tradition sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, spreading through much of Asia. It is the world’s fourth-largest religion[3][4] with over 520 million followers, or over 7% of the global population, known as Buddhists.[5][6] Buddhism encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs and spiritual practices largely based on the Buddha’s teachings (born Siddhārtha Gautama in the 5th or 4th century BCE) and resulting interpreted philosophies.

As expressed in the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths, the goal of Buddhism is to overcome suffering (duḥkha) caused by desire and ignorance of reality’s true nature, including impermanence (anicca) and the non-existence of the self (anattā).[7] Most Buddhist traditions emphasize transcending the individual self through the attainment of Nirvana or by following the path of Buddhahood, ending the cycle of death and rebirth.[8][9][10] Buddhist schools vary in their interpretation of the path to liberation, the relative importance and canonicity assigned to the various Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices.[11][12] Widely observed practices include meditation, observance of moral precepts, monasticism, taking refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha, and the cultivation of the Paramitas (perfections, or virtues).

Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: Theravāda (Pali: “The School of the Elders”) and Mahāyāna (Sanskrit: “The Great Vehicle”). Theravada has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia such as Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand. Mahayana, which includes the traditions of Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren Buddhism, Tiantai Buddhism (Tendai), and Shingon, is practiced prominently in Nepal, Malaysia, Bhutan, China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan. Vajrayana, a body of teachings attributed to Indian adepts, may be viewed as a separate branch or as an aspect of Mahayana Buddhism.[13] Tibetan Buddhism, which preserves the Vajrayana teachings of eighth-century India, is practised in the countries of the Himalayan region, Mongolia,[14] and Kalmykia.[15] Historically, until the early 2nd millennium, Buddhism was also widely practised in Afghanistan and it also had a foothold to some extent in other places including the Philippines, the Maldives, and Uzbekistan.

Life of the Buddha

Ancient kingdoms and cities of India during the time of the Buddha (circa 500 BCE) – modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan

The gilded “Emaciated Buddha statue” in an Ubosoth in Bangkok representing the stage of his asceticism

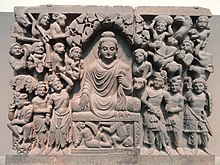

Enlightenment of Buddha, Kushan dynasty, late 2nd to early 3rd century CE, Gandhara.

Buddhism is an Indian religion[16] founded on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, a Śramaṇa also called Shakyamuni (sage of the Shakya’s), or “the Buddha” (“the Awakened One”), who lived c. 5th to 4th century BCE.[17][18] Early texts have the Buddha’s family name as “Gautama” (Pali: Gotama). The details of Buddha’s life are mentioned in many Early Buddhist Texts but are inconsistent. His social background and life details are difficult to prove, and the precise dates are uncertain.[19][note 1]

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhartha Gautama was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal and grew up in Kapilavastu,[note 2] a town in the Ganges Plain, near the modern Nepal–India border, and that he spent his life in what is now modern Bihar[note 3] and Uttar Pradesh.[27][19] Some hagiographic legends state that his father was a king named Suddhodana, his mother was Queen Maya.[28] Scholars such as Richard Gombrich consider this a dubious claim because a combination of evidence suggests he was born in the Shakya community, which was governed by a small oligarchy or republic-like council where there were no ranks but where seniority mattered instead.[29][note 4] Some of the stories about Buddha, his life, his teachings, and claims about the society he grew up in may have been invented and interpolated at a later time into the Buddhist texts.[32][33]

According to early texts such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (“The discourse on the noble quest,” MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204, Gautama was moved by the suffering (dukkha) of life and death, and its endless repetition due to rebirth.[34] He thus set out on a quest to find liberation from suffering (also known as “nirvana”).[35] Early texts and biographies state that Gautama first studied under two teachers of meditation, namely Alara Kalama (Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) and Uddaka Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learning meditation and philosophy, particularly the meditative attainment of “the sphere of nothingness” from the former, and “the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception” from the latter.[36][37][note 5]

Finding these teachings to be insufficient to attain his goal, he turned to the practice of severe asceticism, which included a strict fasting regime and various forms of breath control.[40] This too fell short of attaining his goal, and then he turned to the meditative practice of dhyana. He famously sat in meditation under a Ficus religiosa tree now called the Bodhi Tree in the town of Bodh Gaya and attained “Awakening” (Bodhi).[citation needed]

According to various early texts like the Mahāsaccaka-sutta, and the Samaññaphala Sutta, on awakening, the Buddha gained insight into the workings of karma and his former lives, as well as achieving the ending of the mental defilements (asavas), the ending of suffering, and the end of rebirth in saṃsāra.[40] This event also brought certainty about the Middle Way as the right path of spiritual practice to end suffering.[41][42] As a fully enlightened Buddha, he attracted followers and founded a Sangha (monastic order).[43] He spent the rest of his life teaching the Dharma he had discovered, and then died, achieving “final nirvana,” at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, India.[44][22]

Buddha’s teachings were propagated by his followers, which in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE became various Buddhist schools of thought, each with its own basket of texts containing different interpretations and authentic teachings of the Buddha;[45][46][47] these over time evolved into many traditions of which the more well known and widespread in the modern era are Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.[48][49][note 6]

Classifications

- Theravāda (“Teaching of the Elders”), also called “Southern Buddhism“, mainly dominant in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. This tradition generally focuses on the study of its main textual collection, the Pali Canon as well other forms of Pali literature. The Pali language is thus its lingua franca and sacred language. This tradition is sometimes denominated as a part of Nikaya Buddhism, referring to the conservative Buddhist traditions in India who did not accept the Mahayana sutras into their Tripitaka collection of scriptures. It is also sometimes seen as the only surviving school out of the Early Buddhist schools, being derived from the Sthavira Nikāya via the Sri Lankan Mahavihara tradition.

- East Asian Mahāyāna (“Great Vehicle”), East Asian Buddhism or “Eastern Buddhism“, prominent in East Asia and derived from the Chinese Buddhist traditions which began to develop during the Han Dynasty. This tradition focuses on the teachings found in Mahāyāna sutras (which are not considered canonical or authoritative in Theravāda), preserved in the Chinese Buddhist Canon, in the classical Chinese language. There are many schools and traditions, with different texts and focuses, such as Zen (Chan) and Pure Land (see below).

- Vajrayāna (“Vajra Vehicle”), also known as Mantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism and Esoteric Buddhism. This category is mostly represented in “Northern Buddhism”, also called “Indo-Tibetan Buddhism” (or just “Tibetan Buddhism”), but also overlaps with certain forms of East Asian Buddhism (see: Shingon). It is prominent in Tibet, Bhutan and the Himalayan region as well as in Mongolia and the Russian republic of Kalmykia. It is sometimes considered to be a part of the broader category of Mahāyāna Buddhism instead of a separate tradition. The main texts of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism are contained in the Kanjur and the Tenjur. Besides the study of major Mahāyāna texts, this branch emphasizes the study of Buddhist tantric materials, mainly those related to the Buddhist tantras.

- A fourth branch, Navayāna, is sometimes included as well. It is a re-interpretation of Buddhism by B. R. Ambedkar.[5][6] Ambedkar was born in a Dalit (untouchable) family during the colonial era of India, studied abroad, became a Dalit leader, and announced in 1935 his intent to convert from Hinduism to Buddhism.[7] Thereafter Ambedkar studied texts of Buddhism, found several of its core beliefs and doctrines such as Four Noble Truths and “non-self” as flawed and pessimistic, re-interpreted these into what he called “new vehicle” of Buddhism.[8] Ambedkar held a press conference on October 13, 1956, announcing his rejection of many traditional interpretations of practices and precepts of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism, as well as of Hinduism.[9][10] Thereafter, he left Hinduism and adopted Navayana, about six weeks before his death.[5][8][9] In the Dalit Buddhist movement of India, Navayana is considered a new branch of Buddhism, different from the traditionally recognized branches of Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana. Marathi Buddhists follow Navayana.

Another way of classifying the different forms of Buddhism is through the different monastic ordination traditions. There are three main traditions of monastic law (Vinaya) each corresponding to the first three categories outlined above:

- Theravāda Vinaya

- Dharmaguptaka Vinaya (East Asian Mahayana)

- Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya (Tibetan Buddhism)

Worldview

The term “Buddhism” is an occidental neologism, commonly (and “rather roughly” according to Donald S. Lopez Jr.) used as a translation for the Dharma of the Buddha, fójiào in Chinese, bukkyō in Japanese, nang pa sangs rgyas pa’i chos in Tibetan, buddhadharma in Sanskrit, buddhaśāsana in Pali.[52]

Four Noble Truths – dukkha and its ending

The Buddha teaching the Four Noble Truths. Sanskrit manuscript. Nalanda, Bihar, India.

The Four Truths express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is dukkha, “incapable of satisfying” and painful.[53][54] This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth, dukkha and dying again.[note 7] But there is a way to liberation from this endless cycle[60] to the state of nirvana, namely following the Noble Eightfold Path.[note 8]

The truth of dukkha is the basic insight that life in this mundane world, with its clinging and craving to impermanent states and things[53] is dukkha, and unsatisfactory.[55][66][web 1] Dukkha can be translated as “incapable of satisfying,”[web 5] “the unsatisfactory nature and the general insecurity of all conditioned phenomena”; or “painful.”[53][54] Dukkha is most commonly translated as “suffering,” but this is inaccurate, since it refers not to episodic suffering, but to the intrinsically unsatisfactory nature of temporary states and things, including pleasant but temporary experiences.[note 9] We expect happiness from states and things which are impermanent, and therefore cannot attain real happiness.

In Buddhism, dukkha is one of the three marks of existence, along with impermanence and anattā (non-self).[72] Buddhism, like other major Indian religions, asserts that everything is impermanent (anicca), but, unlike them, also asserts that there is no permanent self or soul in living beings (anattā).[73][74][75] The ignorance or misperception (avijjā) that anything is permanent or that there is self in any being is considered a wrong understanding, and the primary source of clinging and dukkha.[76][77][78]

Dukkha arises when we crave (Pali: taṇhā) and cling to these changing phenomena. The clinging and craving produces karma, which ties us to samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth.[79][web 6][note 10] Craving includes kama-tanha, craving for sense-pleasures; bhava-tanha, craving to continue the cycle of life and death, including rebirth; and vibhava-tanha, craving to not experience the world and painful feelings.[79][80][81]

Dukkha ceases, or can be confined,[82] when craving and clinging cease or are confined. This also means that no more karma is being produced, and rebirth ends.[note 11] Cessation is nirvana, “blowing out,” and peace of mind.[84][85]

By following the Buddhist path to moksha, liberation,[62] one starts to disengage from craving and clinging to impermanent states and things. The term “path” is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of “the path” can also be found in the Nikayas.[86] The Theravada tradition regards insight into the four truths as liberating in itself.[68]

The cycle of rebirth

Traditional Tibetan Buddhist Thangka depicting the Wheel of Life with its six realms

Saṃsāra

Saṃsāra means “wandering” or “world”, with the connotation of cyclic, circuitous change.[87][88] It refers to the theory of rebirth and “cyclicality of all life, matter, existence”, a fundamental assumption of Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions.[88][89] Samsara in Buddhism is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful,[90] perpetuated by desire and avidya (ignorance), and the resulting karma.[88][91][92] Liberation from this cycle of existence, nirvana, has been the foundation and the most important historical justification of Buddhism.[93][94]

Buddhist texts assert that rebirth can occur in six realms of existence, namely three good realms (heavenly, demi-god, human) and three evil realms (animal, hungry ghosts, hellish).[note 12] Samsara ends if a person attains nirvana, the “blowing out” of the afflictions through insight into impermanence and non-self.[96][97][98]

Rebirth

Ramabhar Stupa in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh, India is regionally believed to be Buddha’s cremation site.

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death.[99] In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve a soul or any fixed substance. This is because the Buddhist doctrine of anattā (Sanskrit: anātman, no-self doctrine) rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul found in other religions.[100][101]

The Buddhist traditions have traditionally disagreed on what it is in a person that is reborn, as well as how quickly the rebirth occurs after death.[102][103] Some Buddhist traditions assert that “no self” doctrine means that there is no enduring self, but there is avacya (inexpressible) personality (pudgala) which migrates from one life to another.[102]

The majority of Buddhist traditions, in contrast, assert that vijñāna (a person’s consciousness) though evolving, exists as a continuum and is the mechanistic basis of what undergoes the rebirth process.[55][102] The quality of one’s rebirth depends on the merit or demerit gained by one’s karma (i.e. actions), as well as that accrued on one’s behalf by a family member.[note 13] Buddhism also developed a complex cosmology to explain the various realms or planes of rebirth.[90]

Each individual rebirth takes place within one of five realms according to theravadins, or six according to other schools – heavenly, demi-gods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hellish.[105][106][note 14]

In East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism, rebirth is not instantaneous, and there is an intermediate state (Tibetan “bardo”) between one life and the next.[116][117] The orthodox Theravada position rejects the intermediate state, and asserts that rebirth of a being is immediate.[116] However there are passages in the Samyutta Nikaya of the Pali Canon that seem to lend support to the idea that the Buddha taught about an intermediate stage between one life and the next.[118][119]

Karma

In Buddhism, karma (from Sanskrit: “action, work”) drives saṃsāra – the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being. Good, skilful deeds (Pāli: kusala) and bad, unskilful deeds (Pāli: akusala) produce “seeds” in the unconscious receptacle (ālaya) that mature later either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth.[120][121] The existence of karma is a core belief in Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions, and it implies neither fatalism nor that everything that happens to a person is caused by karma.[122][note 15]

A central aspect of Buddhist theory of karma is that intent (cetanā) matters and is essential to bring about a consequence or phala “fruit” or vipāka “result”.[123][note 16] However, good or bad karma accumulates even if there is no physical action, and just having ill or good thoughts creates karmic seeds; thus, actions of body, speech or mind all lead to karmic seeds.[122] In the Buddhist traditions, life aspects affected by the law of karma in past and current births of a being include the form of rebirth, realm of rebirth, social class, character and major circumstances of a lifetime.[122][127][128] It operates like the laws of physics, without external intervention, on every being in all six realms of existence including human beings and gods.[122][129]

A notable aspect of the karma theory in Buddhism is merit transfer.[130][131] A person accumulates merit not only through intentions and ethical living, but also is able to gain merit from others by exchanging goods and services, such as through dāna (charity to monks or nuns).[132] Further, a person can transfer one’s own good karma to living family members and ancestors.[131][note 17]

Liberation

An aniconic depiction of the Buddha’s spiritual liberation (moksha) or awakening (bodhi), at Sanchi. The Buddha is not depicted, only symbolized by the Bodhi tree and the empty seat.

The cessation of the kleshas and the attainment of nirvana (nibbāna), with which the cycle of rebirth ends, has been the primary and the soteriological goal of the Buddhist path for monastic life since the time of the Buddha.[62][135][136] The term “path” is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of “the path” can also be found in the Nikayas.[note 18] In some passages in the Pali Canon, a distinction is being made between right knowledge or insight (sammā-ñāṇa), and right liberation or release (sammā-vimutti), as the means to attain cessation and liberation.[137][138]

Nirvana literally means “blowing out, quenching, becoming extinguished”.[139][140] In early Buddhist texts, it is the state of restraint and self-control that leads to the “blowing out” and the ending of the cycles of sufferings associated with rebirths and redeaths.[141][142][143] Many later Buddhist texts describe nirvana as identical with anatta with complete “emptiness, nothingness”.[144][145][146][note 19] In some texts, the state is described with greater detail, such as passing through the gate of emptiness (sunyata) – realising that there is no soul or self in any living being, then passing through the gate of signlessness (animitta) – realising that nirvana cannot be perceived, and finally passing through the gate of wishlessness (apranihita) – realising that nirvana is the state of not even wishing for nirvana.[135][148][note 20]

The nirvana state has been described in Buddhist texts partly in a manner similar to other Indian religions, as the state of complete liberation, enlightenment, highest happiness, bliss, fearlessness, freedom, permanence, non-dependent origination, unfathomable, and indescribable.[150][151] It has also been described in part differently, as a state of spiritual release marked by “emptiness” and realisation of non-self.[152][153][154][note 21]

While Buddhism considers the liberation from saṃsāra as the ultimate spiritual goal, in traditional practice, the primary focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists has been to seek and accumulate merit through good deeds, donations to monks and various Buddhist rituals in order to gain better rebirths rather than nirvana.[157][111][note 22]

Dependent arising

Pratityasamutpada, also called “dependent arising, or dependent origination”, is the Buddhist theory to explain the nature and relations of being, becoming, existence and ultimate reality. Buddhism asserts that there is nothing independent, except the state of nirvana.[158] All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other pre-existing states, and in turn from them arise other dependent states while they cease.[159]

The ‘dependent arisings’ have a causal conditioning, and thus Pratityasamutpada is the Buddhist belief that causality is the basis of ontology, not a creator God nor the ontological Vedic concept called universal Self (Brahman) nor any other ‘transcendent creative principle’.[160][161] However, Buddhist thought does not understand causality in terms of Newtonian mechanics, rather it understands it as conditioned arising.[162][163] In Buddhism, dependent arising refers to conditions created by a plurality of causes that necessarily co-originate a phenomenon within and across lifetimes, such as karma in one life creating conditions that lead to rebirth in one of the realms of existence for another lifetime.[164][165][166]

Buddhism applies the theory of dependent arising to explain origination of endless cycles of dukkha and rebirth, through Twelve Nidānas or “twelve links”. It states that because Avidyā (ignorance) exists Saṃskāras (karmic formations) exists, because Saṃskāras exists therefore Vijñāna (consciousness) exists, and in a similar manner it links Nāmarūpa (sentient body), Ṣaḍāyatana (six senses), Sparśa (sensory stimulation), Vedanā (feeling), Taṇhā (craving), Upādāna (grasping), Bhava (becoming), Jāti (birth), and Jarāmaraṇa (old age, death, sorrow, pain).[167][168] By breaking the circuitous links of the Twelve Nidanas, Buddhism asserts that liberation from these endless cycles of rebirth and dukkha can be attained.[169]

Not-Self and Emptiness

A related doctrine in Buddhism is that of anattā (Pali) or anātman (Sanskrit). It is the view that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in phenomena.[170] The Buddha and Buddhist philosophers who follow him such as Vasubandhu and Buddhaghosa, generally argue for this view by analyzing the person through the schema of the five aggregates, and then attempting to show that none of these five components of personality can be permanent or absolute.[171] This can be seen in Buddhist discourses such as the Anattalakkhana Sutta.

“Emptiness” or “voidness” (Skt: Śūnyatā, Pali: Suññatā), is a related concept with many different interpretations throughout the various Buddhisms. In early Buddhism, it was commonly stated that all five aggregates are void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), coreless (asāraka), for example as in the Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (SN 22:95).[172] Similarly, in Theravada Buddhism, it often simply means that the five aggregates are empty of a Self.[173]

Emptiness is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism, especially in Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka school, and in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. In Madhyamaka philosophy, emptiness is the view which holds that all phenomena (dharmas) are without any svabhava (literally “own-nature” or “self-nature”), and are thus without any underlying essence, and so are “empty” of being independent. This doctrine sought to refute the heterodox theories of svabhava circulating at the time.[174]

The Three Jewels

Dharma Wheel and triratna symbols from Sanchi Stupa number 2.

All forms of Buddhism revere and take spiritual refuge in the “three jewels” (triratna): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.[175]

Buddha

While all varieties of Buddhism revere “Buddha” and “buddhahood”, they have different views on what these are. Whatever that may be, “Buddha” is still central to all forms of Buddhism.

In Theravada Buddhism, a Buddha is someone who has become awake through their own efforts and insight. They have put an end to their cycle of rebirths and have ended all unwholesome mental states which lead to bad action and thus are morally perfected.[176] While subject to the limitations of the human body in certain ways (for example, in the early texts, the Buddha suffers from backaches), a Buddha is said to be “deep, immeasurable, hard-to-fathom as is the great ocean,” and also has immense psychic powers (abhijñā).[177]

Theravada generally sees Gautama Buddha (the historical Buddha Sakyamuni) as the only Buddha of the current era. While he is no longer in this world, he has left us the Dharma (Teaching), the Vinaya (Discipline) and the Sangha (Community).[178] There are also said to be two types of Buddhas, a sammasambuddha is also said to teach the Dharma to others, while a paccekabuddha (solitary buddha) does not teach.[176]

Mahāyāna Buddhism meanwhile, has a vastly expanded cosmology, with various Buddhas and other holy beings (aryas) residing in different realms. Mahāyāna texts not only revere numerous Buddhas besides Sakyamuni, such as Amitabha and Vairocana, but also see them as transcendental or supramundane (lokuttara) beings.[179] Mahāyāna Buddhism holds that these other Buddhas in other realms can be contacted and are able to benefit beings in this world.[180] In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is a kind of “spiritual king”, a “protector of all creatures” with a lifetime that is countless of eons long, rather than just a human teacher who has transcended the world after death.[181] Buddha Sakyamuni’s life and death on earth is then usually understood as a “mere appearance” or “a manifestation skilfully projected into earthly life by a long-enlightened transcendent being, who is still available to teach the faithful through visionary experiences.”[181][182]

Dharma

“Dharma” (Pali: Dhamma) in Buddhism refers to the Buddha’s teaching, which includes all of the main ideas outlined above. While this teaching reflects the true nature of reality, it is not a belief to be clung to, but a pragmatic teaching to be put into practice. It is likened to a raft which is “for crossing over” (to nirvana) not for holding on to.[183]

It also refers to the universal law and cosmic order which that teaching both reveals and relies upon.[184] It is an everlasting principle which applies to all beings and worlds. In that sense it is also the ultimate truth and reality about the universe, it is thus “the way that things really are.”

The Dharma is the second of the three jewels which all Buddhists take refuge in. All Buddhas in all worlds, in the past, present and in the future, are believed by Buddhists to understand and teach the Dharma. Indeed, it is part of what makes them a Buddha that they do so.

Sangha

Buddhist monks and nuns praying in the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple of Singapore

The third “jewel” which Buddhists take refuge in is the “Sangha”, which refers to the monastic community of monks and nuns who follow Gautama Buddha’s monastic discipline which was “designed to shape the Sangha as an ideal community, with the optimum conditions for spiritual growth.”[185] The Sangha consists of those who have chosen to follow the Buddha’s ideal way of life, which is one of celibate monastic renunciation with minimal material possessions (such as an alms bowl and robes).[186]

The Sangha is seen as important because they preserve and pass down Buddha Dharma. As Gethin states “the Sangha lives the teaching, preserves the teaching as Scriptures and teaches the wider community. Without the Sangha there is no Buddhism.”[187]

The Sangha also acts as a “field of merit” for laypersons, allowing them to make spiritual merit or goodness by donating to the Sangha and supporting them. In return, they keep their duty to preserve and spread the Dharma everywhere for the good of the world.[188]

The Sangha is also supposed to follow the Vinaya (monastic rule) of the Buddha, thereby serving as an spiritual example for the world and future generations. The Vinaya rules also force the Sangha to live in dependence on the rest of the lay community (they must beg for food etc) and thus draw the Sangha into a relationship with the lay community.[189]

A depiction of Siddhartha Gautama in a previous life prostrating before the past Buddha Dipankara. After making a resolve to be a Buddha, and receiving a prediction of future Buddhahood, he becomes a “bodhisatta”.

There is also a separate definition of Sangha, referring to those who have attained any stage of awakening, whether or not they are monastics. This sangha is called the āryasaṅgha “noble Sangha”.[190] All forms of Buddhism generally reveres these āryas (Pali: ariya, “noble ones” or “holy ones”) who are spiritually attained beings. Aryas have attained the fruits of the Buddhist path.[191] Becoming an arya is a goal in most forms of Buddhism. The āryasaṅgha includes holy beings such as bodhisattvas, arhats and stream-enterers.

Bodhisattva Maitreya, Pakistan (3rd century), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In early Buddhism and in Theravada Buddhism, an arhat (literally meaning “worthy”) is someone who reached the same awakening (bodhi) of a Buddha by following the teaching of a Buddha.[192] They are seen as having ended rebirth and all the mental defilements. A bodhisattva (“a being bound for awakening”) meanwhile, is simply a name for someone who is working towards awakening (bodhi) as a Buddha. According to all the early buddhist schools as well as Theravada, to be considered a bodhisattva one has to have made a vow in front of a living Buddha and also has to have received a confirmation of one’s future Buddhahood.[193] In Theravada, the future Buddha is called Metteyya (Maitreya) and he is revered as a bodhisatta currently working for future Buddhahood.[193]

Mahāyāna Buddhism generally sees the attainment of the arhat as an inferior one, since it is seen as being done only for the sake of individual liberation. It thus promotes the bodhisattva path as the highest and most worthwhile.[194] While in Mahāyāna, anyone who has given rise to bodhicitta (the wish to become a Buddha that arises from a sense of compassion for all beings) is considered a bodhisattva,[195] some of these holy beings (such as Maitreya and Avalokiteshvara) have reached very high levels of spiritual attainment and are seen as being very powerful supramundane beings who provide aid to countless beings through their advanced powers.[196]

Other key Mahāyāna views

Mahāyāna Buddhism also differs from Theravada and the other schools of early Buddhism in promoting several unique doctrines which are contained in Mahāyāna sutras and philosophical treatises.

One of these is the unique interpretation of emptiness and dependent origination found in the Madhyamaka school. Another very influential doctrine for Mahāyāna is the main philosophical view of the Yogācāra school variously, termed Vijñaptimātratā-vāda (“the doctrine that there are only ideas” or “mental impressions”) or Vijñānavāda (“the doctrine of consciousness”). According to Mark Siderits, what classical Yogācāra thinkers like Vasubandhu had in mind is that we are only ever aware of mental images or impressions, which may appear as external objects, but “there is actually no such thing outside the mind.”[197] There are several interpretations of this main theory, many scholars see it as a type of Idealism, others as a kind of phenomenology.[198]

Another very influential concept unique to Mahāyāna is that of “Buddha-nature” (buddhadhātu) or “Tathagata-womb” (tathāgatagarbha). Buddha-nature is a concept found in some 1st-millennium CE Buddhist texts, such as the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras. According to Paul Williams these Sutras suggest that ‘all sentient beings contain a Tathagata’ as their ‘essence, core inner nature, Self’.[199][note 23] According to Karl Brunnholzl “the earliest mahayana sutras that are based on and discuss the notion of tathāgatagarbha as the buddha potential that is innate in all sentient beings began to appear in written form in the late second and early third century.”[201] For some, the doctrine seems to conflict with the Buddhist anatta doctrine (non-Self), leading scholars to posit that the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists.[202][203] This can be seen in texts like the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which state that Buddha-nature is taught to help those who have fear when they listen to the teaching of anatta.[204] Buddhist texts like the Ratnagotravibhāga clarify that the “Self” implied in Tathagatagarbha doctrine is actually “not-self”.[205][206] Various interpretations of the concept have been advanced by Buddhist thinkers throughout the history of Buddhist thought and most attempt to avoid anything like the Hindu Atman doctrine.

These Indian Buddhist ideas, in various synthetic ways, form the basis of subsequent Mahāyāna philosophy in Tibetan Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.

Paths to liberation

While the Noble Eightfold Path is best-known in the West, a wide variety of paths and models of progress have been used and described in the different Buddhist traditions. However, they generally share basic practices such as sila (ethics), samadhi (meditation, dhyana) and prajña (wisdom), which are known as the three trainings. An important additional practice is a kind and compassionate attitude toward every living being and the world. Devotion is also important in some Buddhist traditions, and in the Tibetan traditions visualisations of deities and mandalas are important. The value of textual study is regarded differently in the various Buddhist traditions. It is central to Theravada and highly important to Tibetan Buddhism, while the Zen tradition takes an ambiguous stance.

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (madhyamapratipad). It was a part of Buddha’s first sermon, where he presented the Noble Eightfold Path that was a ‘middle way’ between the extremes of asceticism and hedonistic sense pleasures.[207][208] In Buddhism, states Harvey, the doctrine of “dependent arising” (conditioned arising, pratītyasamutpāda) to explain rebirth is viewed as the ‘middle way’ between the doctrines that a being has a “permanent soul” involved in rebirth (eternalism) and “death is final and there is no rebirth” (annihilationism).[209][210]

Paths to liberation in the early texts

A common presentation style of the path (mārga) to liberation in the Early Buddhist Texts is the “graduated talk”, in which the Buddha lays out a step by step training.[211]

In the early texts, numerous different sequences of the gradual path can be found.[212] One of the most important and widely used presentations among the various Buddhist schools is The Noble Eightfold Path, or “Eightfold Path of the Noble Ones” (Skt. ‘āryāṣṭāṅgamārga’). This can be found in various discourses, most famously in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (The discourse on the turning of the Dharma wheel).

Other suttas such as the Tevijja Sutta, and the Cula-Hatthipadopama-sutta give a different outline of the path, though with many similar elements such as ethics and meditation.[212]

According to Rupert Gethin, the path to awakening is also frequently summarized by another a short formula: “abandoning the hindrances, practice of the four establishings of mindfulness, and development of the awakening factors.”[213]

Noble Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path consists of a set of eight interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead to the cessation of dukkha.[214] These eight factors are: Right View (or Right Understanding), Right Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths, and asserts the path to the cessation of dukkha (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness).[215][216] The path teaches that the way of the enlightened ones stopped their craving, clinging and karmic accumulations, and thus ended their endless cycles of rebirth and suffering.[217][218][219]

The Noble Eightfold Path is grouped into three basic divisions, as follows:[220][221][222]

Theravada presentations of the path

Theravada Buddhism is a diverse tradition and thus includes different explanations of the path to awakening. However, the teachings of the Buddha are often encapsulated by Theravadins in the basic framework of the Four Noble Truths and the Eighthfold Path.[232][233]

Some Theravada Buddhists also follow the presentation of the path laid out in Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga. This presentation is known as the “Seven Purifications” (satta-visuddhi).[234] This schema and its accompanying outline of “insight knowledges” (vipassanā-ñāṇa) is used by modern influential Theravadin scholars, such Mahasi Sayadaw (in his “The Progress of Insight”) and Nyanatiloka Thera (in “The Buddha’s Path to Deliverance”).[235][236]

Mahayana presentations of the path

Mahāyāna Buddhism is based principally upon the path of a Bodhisattva.[237] A Bodhisattva refers to one who is on the path to buddhahood.[238] The term Mahāyāna was originally a synonym for Bodhisattvayāna or “Bodhisattva Vehicle.”[239][240][241]

In the earliest texts of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the path of a bodhisattva was to awaken the bodhicitta.[242] Between the 1st and 3rd century CE, this tradition introduced the Ten Bhumi doctrine, which means ten levels or stages of awakening.[242] This development was followed by the acceptance that it is impossible to achieve Buddhahood in one (current) lifetime, and the best goal is not nirvana for oneself, but Buddhahood after climbing through the ten levels during multiple rebirths.[243] Mahāyāna scholars then outlined an elaborate path, for monks and laypeople, and the path includes the vow to help teach Buddhist knowledge to other beings, so as to help them cross samsara and liberate themselves, once one reaches the Buddhahood in a future rebirth.[237] One part of this path are the pāramitā (perfections, to cross over), derived from the Jatakas tales of Buddha’s numerous rebirths.[244][245]

The doctrine of the bodhisattva bhūmis was also eventually merged with the Sarvāstivāda Vaibhāṣika schema of the “five paths” by the Yogacara school.[246] This Mahāyāna “five paths” presentation can be seen in Asanga’s Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[246]

The Mahāyāna texts are inconsistent in their discussion of the pāramitās, and some texts include lists of two, others four, six, ten and fifty-two.[247][248][249] The six paramitas have been most studied, and these are:[244][249][250]

- Dāna pāramitā: perfection of giving; primarily to monks, nuns and the Buddhist monastic establishment dependent on the alms and gifts of the lay householders, in return for generating religious merit;[251] some texts recommend ritually transferring the merit so accumulated for better rebirth to someone else

- Śīla pāramitā: perfection of morality; it outlines ethical behaviour for both the laity and the Mahayana monastic community; this list is similar to Śīla in the Eightfold Path (i.e. Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood)[252]

- Kṣānti pāramitā: perfection of patience, willingness to endure hardship

- Vīrya pāramitā: perfection of vigour; this is similar to Right Effort in the Eightfold Path[252]

- Dhyāna pāramitā: perfection of meditation; this is similar to Right Concentration in the Eightfold Path

- Prajñā pāramitā: perfection of insight (wisdom), awakening to the characteristics of existence such as karma, rebirths, impermanence, no-self, dependent origination and emptiness;[249][253] this is complete acceptance of the Buddha teaching, then conviction, followed by ultimate realisation that “dharmas are non-arising”.[244]

In Mahāyāna Sutras that include ten pāramitā, the additional four perfections are “skillful means, vow, power and knowledge”.[248] The most discussed pāramitā and the highest rated perfection in Mahayana texts is the “Prajna-paramita”, or the “perfection of insight”.[248] This insight in the Mahāyāna tradition, states Shōhei Ichimura, has been the “insight of non-duality or the absence of reality in all things”.[254][255]

East Asian Buddhism

East Asian Buddhism in influenced by both the classic Indian Buddhist presentations of the path such as the eighth-fold path as well as classic Indian Mahāyāna presentations such as that found in the Da zhidu lun.[256]

There many different presentations of soteriology, including numerous paths and vehicles (yanas) in the different traditions of East Asian Buddhism.[257] There is no single dominant presentation. In Zen Buddhism for example, one can find outlines of the path such as the Two Entrances and Four Practices, The Five ranks, The Ten Ox-Herding Pictures and The Three mysterious Gates of Linji.

Indo-Tibetan Buddhism

In Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, the path to liberation is outlined in the genre known as Lamrim (“Stages of the Path”). All the various Tibetan schools have their own Lamrim presentations. This genre can be traced to Atiśa’s 11th-century A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment (Bodhipathapradīpa).[258]

Common Buddhist practices

Hearing and learning the Dharma

Sermon in the Deer Park depicted at Wat Chedi Liem-Kay

In various suttas which present the graduated path taught by the Buddha, such as the Samaññaphala Sutta and the Cula-Hatthipadopama Sutta, the first step on the path is hearing the Buddha teach the Dharma.[212] This then said to lead to the acquiring of confidence or faith in the Buddha’s teachings.[212]

Mahayana Buddhist teachers such as Yin Shun also state that hearing the Dharma and study of the Buddhist discourses is necessary “if one wants to learn and practice the Buddha Dharma.”[259] Likewise, in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, the “Stages of the Path” (Lamrim) texts generally place the activity of listening to the Buddhist teachings as an important early practice.[260]

Refuge

Traditionally, the first step in most Buddhist schools requires taking of the “Three Refuges”, also called the Three Jewels (Sanskrit: triratna, Pali: tiratana) as the foundation of one’s religious practice.[261] This practice may have been influenced by the Brahmanical motif of the triple refuge, found in the Rigveda 9.97.47, Rigveda 6.46.9 and Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3–4.[262] Tibetan Buddhism sometimes adds a fourth refuge, in the lama. The three refuges are believed by Buddhists to be protective and a form of reverence.[261]

The ancient formula which is repeated for taking refuge affirms that “I go to the Buddha as refuge, I go to the Dhamma as refuge, I go to the Sangha as refuge.”[263] Reciting the three refuges, according to Harvey, is considered not as a place to hide, rather a thought that “purifies, uplifts and strengthens the heart”.[175]

Śīla – Buddhist ethics

Buddhist monks collect alms in Si Phan Don, Laos. Giving is a key virtue in Buddhism.

Śīla (Sanskrit) or sīla (Pāli) is the concept of “moral virtues”, that is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path.[223] It generally consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.[223]

One of the most basic forms of ethics in Buddhism is the taking of “precepts”. This includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (Vinaya or Patimokkha) adopted by a monastery.[264][265]

Other important elements of Buddhist ethics include giving or charity (dāna), Mettā (Good-Will), Heedfulness (Appamada), ‘self-respect’ (Hri) and ‘regard for consequences’ (Apatrapya).

Precepts

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts (Pali: pañcasīla; Sanskrit: pañcaśīla) as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality.[224] It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the monastic rules.[266]

The five precepts are seen as a basic training applicable to all Buddhists. They are:[264][267][268]

- “I undertake the training-precept (sikkha-padam) to abstain from onslaught on breathing beings.” This includes ordering or causing someone else to kill. The Pali suttas also say one should not “approve of others killing” and that one should be “scrupulous, compassionate, trembling for the welfare of all living beings.”[269]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from taking what is not given.” According to Harvey, this also covers fraud, cheating, forgery as well as “falsely denying that one is in debt to someone.”[270]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from misconduct concerning sense-pleasures.” This generally refers to adultery, as well as rape and incest. It also applies to sex with those who are legally under the protection of a guardian. It is also interpreted in different ways in the varying Buddhist cultures.[271]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from false speech.” According to Harvey this includes “any form of lying, deception or exaggeration…even non-verbal deception by gesture or other indication…or misleading statements.”[272] The precept is often also seen as including other forms of wrong speech such as “divisive speech, harsh, abusive, angry words, and even idle chatter.”[273]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from alcoholic drink or drugs that are an opportunity for heedlessness.” According to Harvey, intoxication is seen as a way to mask rather than face the sufferings of life. It is seen as damaging to one’s mental clarity, mindfulness and ability to keep the other four precepts.[274]

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pāli and Sanskrit: ahiṃsa).[275] The Pali Canon recommends one to compare oneself with others, and on the basis of that, not to hurt others.[276] Compassion and a belief in karmic retribution form the foundation of the precepts.[277][278] Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple.[279][280] However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time.[281][280] They are sometimes referred to as the śrāvakayāna precepts in the Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the bodhisattva precepts.[282]

The five precepts are not commandments and transgressions do not invite religious sanctions, but their power has been based on the Buddhist belief in karmic consequences and their impact in the afterlife. Killing in Buddhist belief leads to rebirth in the hell realms, and for a longer time in more severe conditions if the murder victim was a monk. Adultery, similarly, invites a rebirth as prostitute or in hell, depending on whether the partner was unmarried or married.[283] These moral precepts have been voluntarily self-enforced in lay Buddhist culture through the associated belief in karma and rebirth.[284] Within the Buddhist doctrine, the precepts are meant to develop mind and character to make progress on the path to enlightenment.[285]

The monastic life in Buddhism has additional precepts as part of patimokkha, and unlike lay people, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions. Full expulsion from sangha follows any instance of killing, engaging in sexual intercourse, theft or false claims about one’s knowledge. Temporary expulsion follows a lesser offence.[286] The sanctions vary per monastic fraternity (nikaya).[287]

Lay people and novices in many Buddhist fraternities also uphold eight (asta shila) or ten (das shila) from time to time. Four of these are same as for the lay devotee: no killing, no stealing, no lying, and no intoxicants.[288] The other four precepts are:[289][288]

- No sexual activity;

- Abstain from eating at the wrong time (e.g. only eat solid food before noon);

- Abstain from jewellery, perfume, adornment, entertainment;

- Abstain from sleeping on high bed i.e. to sleep on a mat on the ground.

All eight precepts are sometimes observed by lay people on uposatha days: full moon, new moon, the first and last quarter following the lunar calendar.[288] The ten precepts also include to abstain from accepting money.[288]

In addition to these precepts, Buddhist monasteries have hundreds of rules of conduct, which are a part of its patimokkha.[290][note 24]

Vinaya

An ordination ceremony at Wat Yannawa in Bangkok. The Vinaya codes regulate the various sangha acts, including ordination.

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a sangha of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha, a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition.[292] The precise content of the Vinaya Pitaka (scriptures on the Vinaya) differs in different schools and tradition, and different monasteries set their own standards on its implementation. The list of pattimokkha is recited every fortnight in a ritual gathering of all monks.[292] Buddhist text with vinaya rules for monasteries have been traced in all Buddhist traditions, with the oldest surviving being the ancient Chinese translations.[293]

Monastic communities in the Buddhist tradition cut normal social ties to family and community, and live as “islands unto themselves”.[294] Within a monastic fraternity, a sangha has its own rules.[294] A monk abides by these institutionalised rules, and living life as the vinaya prescribes it is not merely a means, but very nearly the end in itself.[294] Transgressions by a monk on Sangha vinaya rules invites enforcement, which can include temporary or permanent expulsion.[295]

Restraint and renunciation

Living at the root of a tree (trukkhamulik’anga) is one of the dhutaṅgas, a series of optional ascetic practices for Buddhist monastics.

Another important practice taught by the Buddha is the restraint of the senses (indriyasamvara). In the various graduated paths, this is usually presented as a practice which is taught prior to formal sitting meditation, and which supports meditation by weakening sense desires that are a hindrance to meditation.[296] According to Anālayo, sense restraint is when one “guards the sense doors in order to prevent sense impressions from leading to desires and discontent.”[296] This is not an avoidance of sense impression, but a kind of mindful attention towards the sense impressions which does not dwell on their main features or signs (nimitta). This is said to prevent harmful influences from entering the mind.[297] This practice is said to give rise to an inner peace and happiness which forms a basis for concentration and insight.[297]

A related Buddhist virtue and practice is renunciation, or the intent for desirelessness (nekkhamma).[298] Generally, renunciation is the giving up of actions and desires that are seen as unwholesome on the path, such as lust for sensuality and worldly things.[299] Renunciation can be cultivated in different ways. The practice of giving for example, is one form of cultivating renunciation. Another one is the giving up of lay life and becoming a monastic (bhiksu o bhiksuni).[300] Practicing celibacy (whether for life as a monk, or temporarily) is also a form of renunciation.[301] Many Jataka stories such as the focus on how the Buddha practiced renunciation in past lives.[302]

One way of cultivating renunciation taught by the Buddha is the contemplation (anupassana) of the “dangers” (or “negative consequences”) of sensual pleasure (kāmānaṃ ādīnava). As part of the graduated discourse, this contemplation is taught after the practice of giving and morality.[303]

Another related practice to renunciation and sense restraint taught by the Buddha is “restraint in eating” or moderation with food, which for monks generally means not eating after noon. Devout laypersons also follow this rule during special days of religious observance (uposatha).[304] Observing the Uposatha also includes other practices dealing with renunciation, mainly the eight precepts.

For Buddhist monastics, renunciation can also be trained through several optional ascetic practices called dhutaṅga.

In different Buddhist traditions, other related practices which focus on fasting are followed.

Mindfulness and clear comprehension

The training of the faculty called “mindfulness” (Pali: sati, Sanskrit: smṛti, literally meaning “recollection, remembering”) is central in Buddhism. According to Analayo, mindfulness is a full awareness of the present moment which enhances and strengthens memory.[305] The Indian Buddhist philosopher Asanga defined mindfulness thus: “It is non-forgetting by the mind with regard to the object experienced. Its function is non-distraction.”[306] According to Rupert Gethin, sati is also “an awareness of things in relation to things, and hence an awareness of their relative value.”[307]

There are different practices and exercises for training mindfulness in the early discourses, such as the four Satipaṭṭhānas (Sanskrit: smṛtyupasthāna, “establishments of mindfulness”) and Ānāpānasati (Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti, “mindfulness of breathing”).

A closely related mental faculty, which is often mentioned side by side with mindfulness, is sampajañña (“clear comprehension”). This faculty is the ability to comprehend what one is doing and is happening in the mind, and whether it is being influenced by unwholesome states or wholesome ones.[308]

Meditation – Samādhi and Dhyāna

Kōdō Sawaki practicing Zazen (“sitting dhyana”)

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but “meditation” primarily refers to the attainment of samādhi and the practice of dhyāna (Pali: jhāna). Samādhi is a calm, undistracted, unified and concentrated state of consciousness. It is defined by Asanga as “one-pointedness of mind on the object to be investigated. Its function consists of giving a basis to knowledge (jñāna).”[306] Dhyāna is “state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi),” reached through focused mental training.[309]

The practice of dhyāna aids in maintaining a calm mind, and avoiding disturbance of this calm mind by mindfulness of disturbing thoughts and feelings.[310][note 25]

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda.[311] While evidence suggests meditation was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha,[312] the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era.[313][314] These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.[315][note 26]

There is no scholarly agreement on the origin and source of the practice of dhyāna. Some scholars, like Bronkhorst, see the four dhyānas as a Buddhist invention.[319] Alexander Wynne argues that the Buddha learned dhyāna from brahmanical teachers.[320]

Whatever the case, the Buddha taught meditation with a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the four dhyānas methodology,[321] in which mindfulness is maintained.[322][323] Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism.[312][324][325] For example, states Bronkhorst, the verse 4.4.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad with its “become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring, concentrated, one sees soul in oneself” is most probably a meditative state.[326] The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of soul and the discussion criticises both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and the “real self, soul” meditation of Hinduism.[327]

Four rupa-jhāna

Seated Buddha, Gal Viharaya, Polonnawura, Sri Lanka.

Buddhist texts teach various meditation schemas. One of the most prominent is that of the four rupa-jhānas (four meditations in the realm of form), which are “stages of progressively deepening concentration”.[328] According to Gethin, they are states of “perfect mindfulness, stillness and lucidity.”[329] They are described in the Pali Canon as trance-like states without desire.[330] In the early texts, the Buddha is depicted as entering jhāna both before his awakening under the bodhi tree and also before his final nirvana (see: the Mahāsaccaka-sutta and the Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta).[331][332]

The four rupa-jhānas are:[328][333]

- First jhāna: the first dhyana can be entered when one is secluded from sensuality and unskillful qualities, due to withdrawal and right effort. There is pīti (“rapture”) and non-sensual sukha (“pleasure”) as the result of seclusion, while vitarka-vicara (thought and examination) continues.

- Second jhāna: there is pīti (“rapture”) and non-sensual sukha (“pleasure”) as the result of concentration (samadhi-ji, “born of samadhi”); ekaggata (unification of awareness) free from vitarka-vicara (“discursive thought”); sampasadana (“inner tranquility”).

- Third jhāna: pīti drops away, there is upekkhā (equanimous; “affective detachment”), and one is mindful, alert, and senses pleasure (sukha) with the body;

- Fourth jhāna: a stage of “pure equanimity and mindfulness” (upekkhāsatipārisuddhi), without any pleasure or pain, happiness or sadness.

There is a wide variety of scholarly opinions (both from modern scholars and from traditional Buddhists) on the interpretation of these meditative states as well as varying opinions on how to practice them.[328][334]

The formless attaiments

Often grouped into the jhāna-scheme are four other meditative states, referred to in the early texts as arupa samāpattis (formless attainments). These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless jhānas (arūpajhānas). The first formless attainment is a place or realm of infinite space (ākāsānañcāyatana) without form or colour or shape. The second is termed the realm of infinite consciousness (viññāṇañcāyatana); the third is the realm of nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana), while the fourth is the realm of “neither perception nor non-perception”.[335] The four rupa-jhānas in Buddhist practice lead to rebirth in successfully better rupa Brahma heavenly realms, while arupa-jhānas lead into arupa heavens.[336][337]

Meditation and insight

Kamakura Daibutsu, Kōtoku-in, Kamakura, Japan.

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; “calm”) and vipassanā (Sanskrit: vipaśyanā, insight).[338] The Buddha compares these mental qualities to a “swift pair of messengers” who together help deliver the message of nibbana (SN 35.245).[339]

The various Buddhist traditions generally see Buddhist meditation as being divided into those two main types.[340][341] Samatha is also called “calming meditation”, and focuses on stilling and concentrating the mind i.e. developing samadhi and the four dhyānas. According to Damien Keown, vipassanā meanwhile, focuses on “the generation of penetrating and critical insight (paññā)”.[342]

There are numerous doctrinal positions and disagreements within the different Buddhist traditions regarding these qualities or forms of meditation. For example, in the Pali Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta (AN 4.170), it is said that one can develop calm and then insight, or insight and then calm, or both at the same time.[343] Meanwhile, in Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośakārikā, vipaśyanā is said to be practiced once one has reached samadhi by cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas).[344]

Beginning with comments by La Vallee Poussin, a series of scholars have argued that these two meditation types reflect a tension between two different ancient Buddhist traditions regarding the use of dhyāna, one which focused on insight based practice and the other which focused purely on dhyāna.[345][346] However, other scholars such as Analayo and Rupert Gethin have disagreed with this “two paths” thesis, instead seeing both of these practices as complementary.[346][347]

The Brahma-vihara

Statue of Buddha in Wat Phra Si Rattana Mahathat, Phitsanulok, Thailand

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called Brahma-viharas, are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm.[348][349][350] These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.[351]

The four Brahma-vihara are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;[349][352]

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta; it is identifying the suffering of others as one’s own;[349][352]

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy;[352]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.[349][352]

According to Peter Harvey, the Buddhist scriptures acknowledge that the four Brahmavihara meditation practices “did not originate within the Buddhist tradition”.[353][note 27] The Brahmavihara (sometimes as Brahmaloka), along with the tradition of meditation and the above four immeasurables are found in pre-Buddha and post-Buddha Vedic and Sramanic literature.[355][356] Aspects of the Brahmavihara practice for rebirths into the heavenly realm have been an important part of Buddhist meditation tradition.[357][358]

According to Gombrich, the Buddhist usage of the brahma-vihāra originally referred to an awakened state of mind, and a concrete attitude toward other beings which was equal to “living with Brahman” here and now. The later tradition took those descriptions too literally, linking them to cosmology and understanding them as “living with Brahman” by rebirth in the Brahma-world.[359] According to Gombrich, “the Buddha taught that kindness – what Christians tend to call love – was a way to salvation.”[360]

Tantra, visualization and the subtle body

An 18th century Mongolian miniature which depicts the generation of the Vairocana Mandala

A section of the Northern wall mural at the Lukhang Temple depicting tummo, the three channels (nadis) and phowa

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity.[361][362] While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.[363]

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also mantra recitation, mandalas, and other elements) are considered to be much more effective than non-tantric meditations and they are one of the most popular meditation methods.[364] The methods of Unsurpassable Yoga Tantra, (anuttarayogatantra) are in turn seen as the highest and most advanced. Anuttarayoga practice is divided into two stages, the Generation Stage and the Completion Stage. In the Generation Stage, one meditates on emptiness and visualizes oneself as a deity as well as visualizing its mandala. The focus is on developing clear appearance and divine pride (the understanding that oneself and the deity are one).[365] This method is also known as deity yoga (devata yoga). There are numerous meditation deities (yidam) used, each with a mandala, a circular symbolic map used in meditation.[366]

In the Completion Stage, one meditates on ultimate reality based on the image that has been generated. Completion Stage practices also include techniques such as tummo and phowa. These are said to work with subtle body elements, like the energy channels (nadi), vital essences (bindu), “vital winds” (vayu), and chakras.[367] The subtle body energies are seen as influencing consciousness in powerful ways, and are thus used in order to generate the ‘great bliss’ (maha-sukha) which is used to attain the luminous nature of the mind and realization of the empty and illusory nature of all phenomena (“the illusory body”), which leads to enlightenment.[368][369]

Completion practices are often grouped into different systems, such as the six dharmas of Naropa, and the six yogas of Kalachakra. In Tibetan Buddhism, there are also practices and methods which are sometimes seen as being outside of the two tantric stages, mainly Mahamudra and Dzogchen (Atiyoga).

Practice: monks, laity

According to Peter Harvey, whenever Buddhism has been healthy, not only ordained but also more committed lay people have practised formal meditation.[370] Loud devotional chanting however, adds Harvey, has been the most prevalent Buddhist practice and considered a form of meditation that produces “energy, joy, lovingkindness and calm”, purifies mind and benefits the chanter.[371]

Throughout most of Buddhist history, meditation has been primarily practised in Buddhist monastic tradition, and historical evidence suggests that serious meditation by lay people has been an exception.[372][373][374] In recent history, sustained meditation has been pursued by a minority of monks in Buddhist monasteries.[375] Western interest in meditation has led to a revival where ancient Buddhist ideas and precepts are adapted to Western mores and interpreted liberally, presenting Buddhism as a meditation-based form of spirituality.[375]

Insight and knowledge

Monks debating at Sera Monastery, Tibet

Prajñā (Sanskrit) or paññā (Pāli) is wisdom, or knowledge of the true nature of existence. Another term which is associated with prajñā and sometimes is equivalent to it is vipassanā (Pāli) or vipaśyanā (Sanskrit), which is often translated as “insight”. In Buddhist texts, the faculty of insight is often said to be cultivated through the four establishments of mindfulness.[376]

In the early texts, Paññā is included as one of the “five faculties” (indriya) which are commonly listed as important spiritual elements to be cultivated (see for example: AN I 16). Paññā along with samadhi, is also listed as one of the “trainings in the higher states of mind” (adhicittasikkha).[376]

The Buddhist tradition regards ignorance (avidyā), a fundamental ignorance, misunderstanding or mis-perception of the nature of reality, as one of the basic causes of dukkha and samsara. Overcoming this ignorance is part of the path to awakening. This overcoming includes the contemplation of impermanence and the non-self nature of reality,[377][378] and this develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and liberates a being from dukkha and saṃsāra.[379][380][381]

Prajñā is important in all Buddhist traditions. It is variously described as wisdom regarding the impermanent and not-self nature of dharmas (phenomena), the functioning of karma and rebirth, and knowledge of dependent origination.[382] Likewise, vipaśyanā is described in a similar way, such as in the Paṭisambhidāmagga, where it is said to be the contemplation of things as impermanent, unsatisfactory and not-self.[383]

Some scholars such as Bronkhorst and Vetter have argued that the idea that insight leads to liberation was a later development in Buddhism and that there are inconsistencies with the early Buddhist presentation of samadhi and insight.[384][385][note 28] However, others such as Collett Cox and Damien Keown have argued that insight is a key aspect of the early Buddhist process of liberation, which cooperates with samadhi to remove the obstacles to enlightenment (i.e., the āsavas).[387][388]

In Theravāda Buddhism, the focus of vipassanā meditation is to continuously and thoroughly know how phenomena (dhammas) are impermanent (annica), not-self (anatta) and dukkha.[389][390] The most widely used method in modern Theravāda for the practice of vipassanā is that found in the Satipatthana Sutta.[391] There is some disagreement in contemporary Theravāda regarding samatha and vipassanā. Some in the Vipassana Movement strongly emphasize the practice of insight over samatha, and other Theravadins disagree with this.[391]

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the development of insight (vipaśyanā) and tranquility (śamatha) are also taught and practiced. The many different schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism have a large repertoire of meditation techniques to cultivate these qualities. These include visualization of various Buddhas, recitation of a Buddha’s name, the use of tantric Buddhist mantras and dharanis.[392][393] Insight in Mahāyāna Buddhism also includes gaining a direct understanding of certain Mahāyāna philosophical views, such as the emptiness view and the consciousness-only view. This can be seen in meditation texts such as Kamalaśīla’s Bhāvanākrama ( “Stages of Meditation”, 9th century), which teaches insight (vipaśyanā) from the Yogācāra-Madhyamaka perspective.[394]

Devotion

Tibetan Buddhist prostration practice at Jokhang, Tibet.

According to Harvey, most forms of Buddhism “consider saddhā (Skt śraddhā), ‘trustful confidence’ or ‘faith’, as a quality which must be balanced by wisdom, and as a preparation for, or accompaniment of, meditation.”[395] Because of this devotion (Skt. bhakti; Pali: bhatti) is an important part of the practice of most Buddhists.[396] Devotional practices include ritual prayer, prostration, offerings, pilgrimage, and chanting.[397] Buddhist devotion is usually focused on some object, image or location that is seen as holy or spiritually influential. Examples of objects of devotion include paintings or statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, stupas, and bodhi trees.[398] Public group chanting for devotional and ceremonial is common to all Buddhist traditions and goes back to ancient India where chanting aided in the memorization of the orally transmitted teachings.[399] Rosaries called malas are used in all Buddhist traditions to count repeated chanting of common formulas or mantras. Chanting is thus a type of devotional group meditation which leads to tranquility and communicates the Buddhist teachings.[400]

In East Asian Pure Land Buddhism, devotion to the Buddha Amitabha is the main practice. In Nichiren Buddhism, devotion to the Lotus Sutra is the main practice. Devotional practices such as pujas have been a common practice in Theravada Buddhism, where offerings and group prayers are made to deities and particularly images of Buddha.[401] According to Karel Werner and other scholars, devotional worship has been a significant practice in Theravada Buddhism, and deep devotion is part of Buddhist traditions starting from the earliest days.[402][403]

Guru devotion is a central practice of Tibetan Buddhism.[404][405] The guru is considered essential and to the Buddhist devotee, the guru is the “enlightened teacher and ritual master” in Vajrayana spiritual pursuits.[404][406] For someone seeking Buddhahood, the guru is the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha, wrote the 12th-century Buddhist scholar Sadhanamala.[406]

The veneration of and obedience to teachers is also important in Theravada and Zen Buddhism.[407]

Vegetarianism and animal ethics

Vegetarian meal at Buddhist temple. East Asian Buddhism tends to promote vegetarianism.

Based on the Indian principle of ahimsa (non-harming), the Buddha’s ethics strongly condemn the harming of all sentient beings, including all animals. He thus condemned the animal sacrifice of the brahmins as well hunting, and killing animals for food.[408] This led to various policies by Buddhist kings such as Asoka meant to protect animals, such as the establishing of ‘no slaughter days’ and the banning of hunting on certain circumstances.[409]

However, early Buddhist texts depict the Buddha as allowing monastics to eat meat. This seems to be because monastics begged for their food and thus were supposed to accept whatever food was offered to them.[410] This was tempered by the rule that meat had to be “three times clean” which meant that “they had not seen, had not heard, and had no reason to suspect that the animal had been killed so that the meat could be given to them”.[411] Also, while the Buddha did not explicitly promote vegetarianism in his discourses, he did state that gaining one’s livelihood from the meat trade was unethical.[412] However, this rule was not a promotion of a specific diet, but a rule against the actual killing of animals for food.[413] There was also a famed schism which occurred in the Buddhist community when Devadatta attempted to make vegetarianism compulsory and the Buddha disagreed.[411]

In contrast to this, various Mahayana sutras and texts like the Mahaparinirvana sutra, Surangama sutra and the Lankavatara sutra state that the Buddha promoted vegetarianism out of compassion.[414] Indian Mahayana thinkers like Shantideva promoted the avoidance of meat.[415] Throughout history, the issue of whether Buddhists should be vegetarian has remained a much debated topic and there is a variety of opinions on this issue among modern Buddhists.

In the East Asian Buddhism, most monastics are expected to be vegetarian, and the practice is seen as very virtuous and it is taken up by some devout laypersons. Most Theravadins in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia do not practice vegetarianism and eat whatever is offered by the lay community, who are mostly also not vegetarians. But there are exceptions, some monks choose to be vegetarian and some abbots like Ajahn Sumedho have encouraged the lay community to donate vegetarian food to the monks.[416] Mahasi Sayadaw meanwhile, has recommended vegetarianism as the best way to make sure one’s meal is pure in three ways.[417] Also, the new religious movement Santi Asoke, promotes vegetarianism. According to Peter Harvey, in the Theravada world, vegetarianism is “universally admired, but little practiced.”[417] Because of the rule against killing, in many Buddhist countries, most butchers and others who work in the meat trade are non-Buddhists.[418]

Likewise, most Tibetan Buddhists have historically tended not to be vegetarian, however, there have been some strong debates and pro-vegetarian arguments by some pro-vegetarian Tibetans.[419] Some influential figures have spoken and written in favor of vegetarianism throughout history, including well known figures like Shabkar and the 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje, who has mandated vegetarianism in all his monasteries.[420]

Buddhist texts

A depiction of the supposed First Buddhist council at Rajgir. Communal recitation was one of the original ways of transmitting and preserving Early Buddhist texts.

Buddhism, like all Indian religions, was initially an oral tradition in ancient times.[421] The Buddha’s words, the early doctrines, concepts, and their traditional interpretations were orally transmitted from one generation to the next. The earliest oral texts were transmitted in Middle Indo-Aryan languages called Prakrits, such as Pali, through the use of communal recitation and other mnemonic techniques.[422]

The first Buddhist canonical texts were likely written down in Sri Lanka, about 400 years after the Buddha died.[421] The texts were part of the Tripitakas, and many versions appeared thereafter claiming to be the words of the Buddha. Scholarly Buddhist commentary texts, with named authors, appeared in India, around the 2nd century CE.[421] These texts were written in Pali or Sanskrit, sometimes regional languages, as palm-leaf manuscripts, birch bark, painted scrolls, carved into temple walls, and later on paper.[421]

Unlike what the Bible is to Christianity and the Quran is to Islam, but like all major ancient Indian religions, there is no consensus among the different Buddhist traditions as to what constitutes the scriptures or a common canon in Buddhism.[421] The general belief among Buddhists is that the canonical corpus is vast.[423][424][425] This corpus includes the ancient Sutras organised into Nikayas or Agamas, itself the part of three basket of texts called the Tripitakas.[426] Each Buddhist tradition has its own collection of texts, much of which is translation of ancient Pali and Sanskrit Buddhist texts of India. The Chinese Buddhist canon, for example, includes 2184 texts in 55 volumes, while the Tibetan canon comprises 1108 texts – all claimed to have been spoken by the Buddha – and another 3461 texts composed by Indian scholars revered in the Tibetan tradition.[427] The Buddhist textual history is vast; over 40,000 manuscripts – mostly Buddhist, some non-Buddhist – were discovered in 1900 in the Dunhuang Chinese cave alone.[427]

Early Buddhist texts

Gandhara birchbark scroll fragments (c. 1st century) from British Library Collection