1. Buyer Purchase Criteria

Applying these fundamentals of buyer value to a particular industry results in the identification of buyer purchase criteria—specific attributes of a firm that create actual or perceived value for the buyer. Buyer purchase criteria can be divided into two types:

- Use criteria. Purchase criteria that stem from the way in which a supplier affects actual buyer value through lowering buyer cost or raising buyer performance. Use criteria might include such factors as product quality, product features, delivery time, and applications engineering support.

- Signaling criteria. Purchase criteria that stem from signals of value, or means used by the buyer to infer or judge what a supplier’s actual value Signaling criteria might include factors such as advertising, the attractiveness of facilities, and reputation.

Use criteria are specific measures of what creates buyer value. Signaling criteria are measures of how buyers perceive the presence of value. While use criteria tend to be more oriented to a supplier’s product, outbound logistics and service activities, signaling criteria often stem from marketing activities. Nonetheless, every functional department of a firm (and most every value activity) can affect both.

The price premium a firm can command will be a function of its uniqueness in meeting both use and signaling criteria. Addressing use criteria without also meeting signaling criteria, a common error, will undermine a buyer’s perception of a firm’s value. Addressing signaling criteria without meeting use criteria will also usually not succeed because buyers will eventually realize that their substantive needs have gone unmet.

The distinctions among use and signaling criteria are often complex, since many of a firm’s activities contribute to meeting use criteria as well as serve as signals of value. A polished sales force, for example, may both signal value and be a valuable source of applications knowledge that will lower the buyer’s cost. Similarly, brand reputation may be valuable to a buyer because it removes any blame if a supplier does not perform (“How can you blame me for selecting IBM?”). Despite such situations, however, it is vital to separate use and signaling criteria and the firm’s activities that contribute to both, since only use criteria represent true sources of buyer value. Buyers do not pay for signals of value per se. A firm must understand how well it meets use criteria and the value created in order to determine an appropriate price premium. The value of meeting signaling criteria is measured differently. The value of a signaling criterion is how much it contributes to the buyer perceiving the value created in meeting use criteria.

USE CRITERIA

Use criteria grow out of links between a firm’s value chain and its buyer’s value chain, as described earlier. Because these links are numerous, there are often many use criteria that go well beyond characteristics of the physical product. Use criteria can encompass the actual product (e.g., Dr Pepper’s taste difference from Coca-Cola and Pepsi), or the system by which a firm delivers and supports its product, even if the physical product is undifferentiated. While the distinction between a product and other value activities may only be a matter of degree, it remains an important one since other value activities often provide more dimensions on which to differentiate than the physical product. Other value activities besides those associated with the product can represent an important source of differentiation because many firms tend to be preoccupied with the physical product. Use criteria can also include both the specifications achieved by a firm’s product (or other value activities) as well as the consistency with which it meets those specifications (conformance). Conformance may be as important as or more important than specifications, although it too is often overlooked as a differentiating factor.

Use criteria can also include intangibles such as style, prestige, perceived status, and brand connotation (e.g., designer jeans), particularly in consumer goods. Intangible use criteria often stem from purchase motivations that are not economic in the narrow sense. Smirnoff Vodka’s ability to achieve a premium price for a product that is essentially a commodity stems largely from the social context in which much drinking takes place. Buyers want to be seen consuming sophisticated vodka or to serve vodka perceived as such by their guests. While intangible use criteria are usually associated with consumers, they can be equally important with other buyers. Owning a Gulfstream III business jet can lead to considerable prestige for executives with their peers, for example. Intangible use criteria are most important in industrial, commercial, or institutional products where the real buyer is an individual with considerable discretion in purchasing.

Finally, use criteria also may encompass the characteristics of distribution channels, or downstream value. Since channels can contribute to differentiation, use criteria must reflect these in areas such as channel-provided service, and credit provided by channels. In addi-tion, channels will have their own use criteria that measure sources of value in a firm’s dealings with them. For example, channels will often want credit, responsiveness to inquiries, or technical support that the end buyer may not notice at all.

Since the performance of a firm in meeting use criteria may also be affected by how the buyer actually uses a product, part of a firm’s challenge is to ensure that its product is actually used in a way that allows it to perform to its capabilities. This can be influenced by product design, packaging, and training. Flow control valves, for example, are often designed so they cannot be overtorqued. Factors that improve the chances that a product is used as intended often become use criteria in their own right. They may be potential bases for differentiation since firms often assume that their products are used as intended.

SIGNALING CRITERIA

Signaling criteria reflect the signals of value that influence the buyer’s perception of the firm’s ability to meet its use criteria. Activities a firm performs, as well as other attributes, can be signaling criteria. Signaling criteria may help a particular supplier to be considered and/or may play an important role in the buyer’s final purchase decision. Typical signaling criteria include:

- reputation or image

- cumulative advertising

- weight or outward appearance of the product

- packaging and labels

- appearance and size of facilities

- time in business

- installed base

- customer list

- market share

- price (where price connotes quality)

- parent company identity (size, financial stability, )

- visibility to top management of the buying firm

Often signaling criteria can be quite subtle. For example, the paint job on a medical instrument may have an important impact on the buyer’s perception of its quality even though the paint job has little or no impact on the instrument’s performance. Similarly, Arm & Hammer’s brand extension into detergents has been perceived as differentiated in part because a box of it is heavier than competitors’ products even though it yields the same number of washes.

Signaling criteria are the most important when buyers have a difficult time measuring a firm’s performance, they purchase the product infrequently, or the product is produced to buyer specifications and hence past history with other buyers is an incomplete indication of the future. In professional services, for example, signaling criteria are extremely important. Services are typically customized and actually performed only after the buyer has purchased them. As a result, successful professional service firms pay very close attention to such things as office decor and the appearance of employees. Another industry where signaling criteria are important is pianos, where many buyers are not sophisticated or secure enough to judge quality very accurately. Steinway, the differentiated producer, has recognized the use of pianos by concert pianists as a powerful signaling criterion. Steinway maintains a “piano bank” of grand pianos all over the United States that approved artists can use for concerts at a nominal cost.39 As a result, Steinway has developed excellent artist relationships, and a large percentage of concerts are performed on Steinway pianos.

Signaling criteria also grow out of the need to reinforce the buyer’s perception of a firm even after the purchase of the product. Buyers often need continued reassurance that they made a good decision in choosing the firm and the product. They may also need education to help them evaluate the extent to which a product is meeting their use criteria. This is because buyers often remain unable to discern how well a product has met their use criteria even after purchase, and may have insufficient data or may not pay enough attention to notice product performance. Regular communication that describes a firm’s contribution for its buyers can often have a major impact on differentiation.

Some signaling criteria are associated with particular use criteria, while others are more generalized signals that a supplier will provide value to the buyer. Advertising may emphasize product characteristics, for example, while a firm’s reputation may imply to some buyers that many of their criteria will be satisfied. It is important to attempt to draw the connections between signals of value and the particular use criteria they are signaling. This will both help in identifying additional signals of value, and help the firm understand exactly those attributes its signaling should convey. If a firm recognizes that its customer list is a signal of service reliability, for example, it can present the list in a form that emphasizes this.

2. Identifying Purchase Criteria

Identification of purchase criteria begins by identifying the decision maker for a firm’s product and the other individuals that influence the decision maker. The channels may be an intermediate buyer that must be analyzed as well. Use criteria should be identified first, because they measure the sources of buyer value and also often determine signaling criteria. A number of parallel approaches should be employed to identify use criteria. Internal knowledge of the buyer’s needs constitutes an initial source of use criteria. However, conventional wisdom may color internal perception of use criteria; an internal analysis alone is insufficient. No analysis of buyer purchase criteria should ever be accepted unless it includes some direct contact with the buyer. However, even talking to buyers, as essential as it is, is insufficient because buyers often do not fully understand all the ways in which a firm can affect their cost or performance and they may also not tell the truth. In any serious effort to understand buyer purchase criteria, then, a firm must identify the buyer’s value chain and perform a systematic analysis of all existing and potential linkages between a firm’s value chain and its buyer’s chain. This sort of analysis can not only uncover unrecognized use criteria, but also show how to assess the relative weight of well-known use criteria.

Use criteria must be identified precisely in order to be meaningful for developing differentiation strategy. Many firms speak of their buyers’ use criteria in vague terms such as “high quality” or “delivery.” At this level of generality, a firm cannot begin to calculate the value of meeting a use criterion to the buyer, nor can the firm know how to change its behavior to increase buyer value. Quality could mean higher specifications or better conformance, for example. For McDonald’s, consistency of hamburger and french fry quality over time and across locations is important as is taste and portion size. Improving these two things involves very different actions by a firm. Service can also mean many things, including backing of claims, repair capability, response time to service requests, and delivery time.

Good performance in meeting each use criteria should be quanti-fied if possible. For example, the quality of a food ingredient might be measured in terms of the particle count of extraneous material or the percentage of fat content.11 Quantification not only forces careful thinking to determine what precisely the buyer values, but also allows the measurement and tracking of firm performance against a use criterion—this often yields major improvements in performance in and of itself. Quantification also allows a firm to assess its position against competitors in meeting important criteria. The firm can then study the practices that underlie competitors’ performance.

A firm can calculate the value of meeting each use criterion by estimating how it affects the buyer’s cost or performance. Such calculations inevitably involve judgments, but are an indispensable tool in choosing a sustainable differentiation strategy.12 Determining the buyer value in meeting each use criterion will allow them to be ranked in order of importance. For some use criteria a firm must only meet a threshold value to satisfy the buyer’s need, while for others more performance against them is always better. If a TV set warms up in two seconds, for example, there is little additional benefit if the time is reduced to one second. Nearly all use criteria will reach a point of diminishing returns, however, after which further improvement is not valuable or will actually reduce buyer value. Meeting some use criteria may also involve tradeoffs with others. Calculating the buyer value from meeting each use criterion will illuminate the relevant thresholds, tradeoffs, and buyer value that accrues to additional improvement in meeting it. A firm can only make its own assessments of the balance between the value of differentiation and its cost if it understands these things. The ranking of use criteria in terms of the buyer value of meeting them will often contradict conventional wisdom.

Signaling criteria can be identified by understanding the process the buyer uses to form judgments about a firm’s potential ability to meet use criteria, as well as how well it is actually meeting them. Examining each use criteria to determine possible signals is a good place to start. If a key use criterion is reliability of delivery, for example, past delivery record and customer testimonials might be signals of value. Two other analytical steps can also provide insight into signals of value. By carefully analyzing the process by which the buyer pur-chases, including the information sources consulted, the testing or inspection procedures carried out, and the steps in reaching the decision, signals of value may become apparent. This sort of analysis will yield indications about what a buyer consults or notices, including channels. A related way of identifying signaling criteria is to identify significant points of contact between a firm and the buyer both before and after purchase, including the channels, trade shows, accounting department, and others. Every point of contact represents an opportunity to influence the buyer’s perception of a firm and thus is a possible signaling criterion.

Like use criteria, signaling criteria should be defined as precisely and operationally as possible in order to guide differentiation strategy. In a bank, for example, the appearance of facilities can signal value through its order, permanence, and security. For a designer clothing store, other dimensions of appearance would be more appropriate. Signaling criteria vary in importance, and a firm must rank them in terms of their impact on buyer perception in order to make choices about how much to spend on them. Calculating the contribution of signaling criteria to realized price is often difficult, but focus groups and interviews may be helpful. As with use criteria, meeting signaling criteria can reach the point of diminishing returns. Opulent offices, for example, may disillusion a buyer by making a firm appear wasteful or unprofessional.

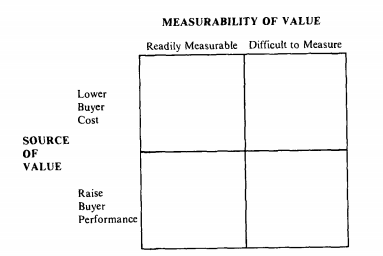

The process of identifying buyer purchase criteria should result in a ranking and sorting of purchase criteria such as that in Figure 4-4, which illustrates purchase criteria for a chocolate confection product. Price should be included in the list corresponding to the ranking the buyer places on it. Use and the end user and the channel should be separated, to highlight the different entities involved and to clarify the actions required to meet each criterion. Use criteria for both end users and channels can be usefully divided into those factors that lower buyer cost and those that raise buyer performance. While meeting a use criterion can sometimes both lower cost and raise performance, often one or the other modes of value creation is predominant—in the chocolate confection example taste relates to buyer performance while availability is predominantly a measure of buyer shopping cost. Then use criteria can be further divided into those that are easy to measure and those that are difficult for the buyer to perceive and/or quantify (see Figure 4-5).

Figure 4 -4 . Ranked Buyer Purchase Criteria for a Chocolate Confection

Figure 4-5. The Relationship Between Use Criteria and Buyer Value

Recognizing the differences in use criteria represented in Figure 4-5 can be important for a number of reasons. Differentiation that lowers buyer cost provides a more persuasive justification for paying a sustained price premium with some buyers than differentiation that raises performance. Financial pressures on buyers (such as in a downturn) often mean that buyers are willing to pay a premium only to firms that can demonstrate persuasively that they lower buyers’ cost. Differentiation with a readily measurable connection to buyer value is also frequently more translatable into a price premium than differentiation that creates value in ways that are hard to perceive or measure.

Differentiation that is difficult to measure tends to translate into a price premium primarily in situations where the buyer perceives a great deal to be at stake, such as in top level consulting or where the buyer is seeking to meet status needs. Differentiation on the right- hand side of Figure 4-5 tends to be expensive to explain, requiring high levels of investment in signaling. Increasing buyer sophistication tends to threaten difficult-to-measure forms of differentiation that may have been accepted at face value in the past.

Each individual buyer to which an industry sells may have a different set of use and signaling criteria or may rank among them differently. Clustering of buyers into groups based on similarities in their purchase criteria is one basis of buyer segments, to which I will return in Chapter 7.

Source: Porter Michael E. (1998), Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press; Illustrated edition.