Competitor interrelationships are present when a firm actually or potentially competes with diversified rivals in more than one business unit. Any action taken against multipoint competitors must consider the entire range of jointly contested businesses. In addition, a firm’s competitive advantage vis-à- vis a multipoint competitor depends in part on the interrelationships that both have achieved. The competitive position of a multipoint competitor is often more a function of its overall position in a group of related industries than its market share in any one industry because of interrelationships. While multipoint competitors and interrelationships do not necessarily occur together, they often do because both tangible and intangible interrelationships lead firms to follow parallel diversification paths.

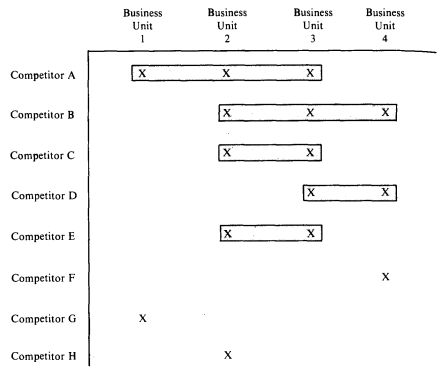

Figure 9-4. Corporate Competitor Matrix

Identifying existing multipoint competitors is relatively easy with a diagram such as that shown in Figure 9-4. For the firm shown in Figure 9-4, competitors A, B, C, D, and E are multipoint competitors. The other competitors are single point, but represent potential multipoints. Analysis of the figure suggests that business units 2 and 3 are in strongly related industries, because four competitors compete in both industries. The presence of many competitors in two industries is a relatively strong, though not perfect, indication that they are related. The relatedness of industries is also a clue to predicting which firms are the most likely potential multipoint competitors. Given the apparent relationship of the industries in which business units 2 and 3 compete, competitor H may be the most likely potential multipoint competitor.

Table 9-6 shows the multipoint competitor matrix for the consumer paper products sector in 1983, along with each firm’s year of entry. It is clear that competitor interrelationships are numerous and that they have increased significantly over time, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s. We would observe a similar pattern in many other groups of industries. The pattern of competitor interrelationships in the table will be discussed further below.

Closely analagous to the analysis of multipoint competitors is the analysis of single-point competitors with different patterns of interrelationships from the firm’s. For example, Xerox, Canon, and Matsushita all compete in convenience copiers. However, Xerox draws on interrelationships with its high-volume copiers and office automation equipment. Canon’s interrelationships have historically been strongest with its calculator and camera businesses, while Matsushita draws on interrelationships involving its broad range of consumer electronic and other electronic products. Interestingly, both Canon and Matsu- shita are diversifying into office automation to match Xerox’s interrelationships there.

Single-point competitors with different patterns of interrelationships are important because they bring differing sources of competitive advantage to an industry. These may be difficult for a firm to match and may shift the basis of competition. Moreover, as the copier example illustrates, single-point competitors with different patterns of interrelationships are sometimes prime candidates to become multipoint competitors.

1. Multipoint Competitors in Unrelated Industries

Where a firm faces a multipoint competitor in industries that are not related, the strategic issues revolve around how actions in one business unit can lead to reactions in another and how equilibrium with the competitor can be reached in several contested industries. Because a firm and a multipoint competitor meet each other in a number of industries rather than one, a greater number of variables enter into determining their relative position. This implies that firms need more information about each other to avoid mistaken interpreta- tions of moves. It also often means that destabilizing events in one industry can spread to others. This added complexity of the game makes peaceful coexistence potentially difficult.

TABLE 9-6 Competitor Interrelationships in Consumer Paper Products, 1983

On the other hand, competing in a number of industries also opens up greater possibilities for signaling, making threats, establishing blocking positions, and taking reciprocal actions. For example, a firm threatened in one industry might retaliate in a different industry, sending a signal of displeasure but creating less risk of escalation than if the response were direct. The threat that a firm can retaliate in several industries (and inflict a higher cost on the competitor) may also tend to deter a competitor from making a threatening move in the first place.

Another stabilizing factor in multipoint competition is the fact that focal points, or natural equilibrium points for competition, may be more prevalent.78 Where only one industry is contested, the number of focal points consistent with each competitor’s perception of its relative strength is likely to be small. With equally balanced competitors, for example, an equal division of market shares may be the only focal point. It may well be an unstable one because any temporary shift in market shares is likely to trigger a strong response to preserve the balance. With two jointly contested industries, there may be a number of additional focal points that are more stable, and one of them will tend to be found sooner.

Table 9-7 illustrates this. Here focal points 2 and 3 will tend to be more stable than focal point 1. In each industry, the high-share competitor will tend to have a clear competitive advantage, and hence a small disturbance will be less likely to cause either firm to precipitate a war. Similarly, the asymmetry of positions reduces the chances that the high-share competitor in one industry will seek an even greater share, since it remains vulnerable to retaliation in the industry in which it is weak.

Multipoint competitors must be viewed in their totality for purposes of offensive and defensive strategy. Most competitor analysis is done at the business unit level, however, and looks exclusively at competitors’ positions in a single industry. Some corporate or group- level analysis of multipoint competitors is essential. Minimally, a broader perspective on multipoint competitors needs to be applied to test that business unit actions against them will not have adverse consequences in other business units. Ideally a more comprehensive analysis of existing and potential multipoint competitors should be done to uncover opportunities for a coordinated offensive or defensive strategy across business units.

Some additional considerations in developing strategy vis-a-vis multipoint competitors in unrelated businesses are as follows:

Forecast possible retaliation in all jointly contested industries. A multipoint competitor may retaliate against a move in any or all jointly contested industries. It may well choose to respond in the industry where its response will be the most cost-effective (see Chapter 14). For example, it may respond in an industry in which it has a small share because it can inflict a large penalty on the firm at low cost. Each industry is not a separate battlefield.

Beware of a small position by a multipoint in a key industry. A small position held by a multipoint in an industry in which the firm has a large share (or high cash flow) can give the multipoint a lever against the firm. Such a position may be an effective blocking position (see Chapter 14).

Look for opportunities to exploit overall corporate position vis-à- vis a multipoint. The overall corporate position vis-à-vis a multipoint may provide less costly and less risky means of responding to threats. Similarly, coordinated actions in a number of industries may make it difficult and very costly for a competitor to respond.

Establish blocking positions for defensive purposes. A small presence in one of a multipoint competitor’s key industries can provide a way to inflict serious penalties on it at relatively low cost.

Strategy toward a multipoint competitor is affected by whether or not the competitor perceives the connections among industries. Perceiving the connection among jointly contested industries cannot be assumed where a multipoint competitor is managed via highly autonomous business units. In some cases, a competitor’s ignorance of multiindustry linkages may allow the firm to gain in relative position. For example, an attack on one business unit may divert competitor attention and resources from defending its position in a more important business unit.

2. Multipoint Competition in Related Industries

When a firm faces multipoint competitors in related industries, the strategic problem increases in complexity. The issues discussed in the previous section still apply and are often even more important because relatedness increases the likelihood that a competitor will perceive the linkages among businesses. The presence of tangible interrelationships among industries, however, complicates the assessment of relative position.

A firm’s competitive advantage or disadvantage in any business unit that faces a multipoint competitor is a function of overall position in value activities involving interrelationships. If a firm and the competitor employ a shared sales force or logistical system, for example, the relative cost or differentiation of the sales force or logistical system as a whole is what matters. The extent to which interrelationships are actually achieved is what determines their effect on competitive advantage, not the potential to share. In addition, the net competitive advantage from an interrelationship for both a firm and a competitor will be influenced by their respective strategies. A competitor may potentially face higher or lower costs of coordination or compromise than the firm does, making an interrelationship more or less valuable to it.

A competitor’s group of interrelated business units may not exactly overlap with the firm’s. For example, Procter & Gamble competes in disposable diapers, paper towels, feminine hygiene products, and bathroom tissue, but not in paper napkins and towel wipes. Kimberly Clark, on the other hand, is in all these businesses. When the related industries that are jointly contested do not overlap exactly, the comparison between a firm and a competitor must center on the firm’s whole array of interrelationships relative to the competitor’s. Each shared activity must be analyzed for the competitor as a whole, and compared to the firm’s cost or differentiation in that activity. The volume provided by all five of Procter & Gamble’s paper-related business units compared to that of Kimberly’s eight business units will affect their relative position in shared value activities such as the logistical system, for example. Relative position in any business unit is built up by comparing all shared activities as well as value activities that are not shared.

A weak relative position in one related business unit can be partially or completely offset by superior positions in other related business units. Procter & Gamble is in fewer paper products industries than Kimberly-Clark, for example, but it is the market leader in diapers, toilet tissue, and paper towels. Diapers, particularly, is a very large industry relative to the others. Procter & Gamble’s total consumer paper products volume is undoubtedly higher than Kimberly’s. Analyzing a firm’s relative position vis- à-vis multipoint competitors thus requires an examination of the complete portfolios of the two firms.

The most basic strategic implication of multipoint competition in related industries is the same as in unrelated industries—competitor analysis must encompass the competitor’s entire portfolio of business units instead of examining each business unit in isolation. Competitive advantage in one business unit can be strongly affected by the extent of potential interrelationships with other business units in the competitor’s portfolio and by whether they are achieved.

Balance or superiority in shared value activities relative to a multipoint competitor can potentially be achieved in many ways. Investing to gain a stronger position in industries where a firm is already strong can offset the advantages a competitor has from being in a broader array of related industries. If the competitive advantage from shared activities is significant and no compensating advantages can be found, a firm may be forced to match a competitor’s portfolio of related business units. Matching can be important for defensive reasons as well as offensive ones. It may be necessary to match a competitor’s diversification even if the firm has a competitive advantage in its existing business units, to prevent the competitor from gaining the advantages of interrelationships without opposition. Conversely, if a firm can discover new related industries that competitors are not in, it may be able to strengthen position in important shared value activities.

In consumer paper products, for example, there has been a great deal of offensive and defensive diversification. Table 9-6 shows the dates of entry of each competitor into the respective industries. Competitors’ portfolios of businesses have broadened since the late 1950s. Procter & Gamble’s actions triggered this sequence of moves. P&G began in toilet tissue and then moved into facial tissue, disposable diapers, and paper towels defensively.

3. Competitors with Different Patterns of Interrelationships

Single-point and multipoint competitors may well pursue different types of interrelationships, involving different shared activities or activities shared in a different way. A good example of this situation is again the consumer paper products field (Table 9-6). Competitors have pursued interrelationships in paper products in different ways, reflecting their overall portfolios of business units and the strategies employed in them. In disposable diapers, for example, Procter & Gamble enjoys joint procurement of common raw materials, shared technology development, a shared sales force, and a shared logistical system among its paper product lines. However, Procter & Gamble has separate brand names for each paper product line. In contrast, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) competes in disposable diapers as well as a wide line of other baby care products, all sold under the Johnson & Johnson brand name. Its interrelationships include that shared brand name, plus a shared sales force and shared market research in the baby care field. J&J enjoys little sharing in production, logistics, and product or process technology development. Each competitor in Table 9-6 has a somewhat different pattern of interrelationships.

A competitor with a different pattern of interrelationships represents both an opportunity and a threat. It is a threat because the competitive advantage gained through interrelationships cannot be readily replicated, since a firm may not be in the appropriate group of industries, or have the right strategy to allow matching the interrelationships. To match J&J’s shared brand name, for example, Procter & Gamble would have to change its strategy of using a different brand for each product. This would probably fail, however, because of the inappropriateness of using the diaper brand name on other paper products unrelated to babies. Thus to match this particular advantage of J&J’s, Procter & Gamble would probably have to diversify further into baby care, where J&J is dominant.

A smart competitor with different interrelationships will attempt to shift the nature of competition in each industry in the direction that makes its interrelationships more strategically valuable than the firm’s. An escalation in advertising spending in diapers would work to the advantage of J&J because of its shared brand, for example, holding other things constant. A competitor with different interrelationships might also attempt to reduce the ability of a firm to achieve its interrelationships. For example, a move by J&J to make diapers from textile-based materials would, if feasible, reduce P&G’s ability to share value activities because of its broad presence in paper products. Similarly, a competitor might shift its strategy in a way that raised the cost of compromise for the firm to achieve its type of interrelationships, thereby forcing the firm to damage one business unit in responding to a threat to another.

Thus the essence of the competitive game between firms pursuing different forms of interrelatedness is a tug of war to see which firm can shift the basis of competition to compromise the other’s interrelationships, or to enhance the value of its own. The disposable diaper industry offers a good illustration of how this game can play itself out. Procter & Gamble has retained leadership in the diaper industry, while J&J was forced to exit from the U.S. market after costly losses. Though J&J’s market interrelationships were strong, advertising is a relatively small proportion of total costs in disposable diapers. Sales force and logistical costs, where Procter & Gamble enjoyed comparable if not superior interrelationships to J&J, are each as high or higher than advertising. J&J could not match Procter & Gamble’s production, procurement, and technological interrelationships, and this proved fatal since total manufacturing costs for diapers are a very large percentage of total cost and the pace of technological change in both product and process is rapid. Without a markedly superior product, therefore, J&J was unable to match the combination of Procter & Gamble’s large market share and its interrelationships.

4. Forecasting Potential Competitors

Tangible interrelationships, intangible interrelationships, and competitor interrelationships can be used to forecast likely potential competitors. Likely potential entrants into an industry will be firms for which that industry is:

- a logical way to create or extend an important interrelationship

- a necessary extension to match the interrelationships of competitors

To forecast potential competitors, all possible interrelationships involving an industry are identified, including competitor interrelationships. Each potential interrelationship will typically lead to a number of other industries. The industries in which existing competitors compete besides the industry may suggest possible interrelationships of other types. By identifying related industries, a firm can locate potential competitors for whom entry into the firm’s industries would be logical. Analysis must assess the probability that these potential competitors will actually choose to enter the industry rather than pursue their other investment opportunities.

Source: Porter Michael E. (1998), Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press; Illustrated edition.