It is somewhat arbitrary to distinguish the processes involved in creat- ing institutions from those employed to change them. Institutions do not emerge in a vacuum; they always challenge, borrow from, and, to varying degrees, displace prior institutions. The difference lies largely in the investigator’s focus. If attention is directed primarily to the pro- cesses and conditions giving rise to new rules, understandings, and associated practices, then we have a study of institutional creation. As Greif (2006: 17) points out: “Beliefs, norms, and organizations inherited from the past will constitute part of the initial conditions in the pro- cesses leading to new institutions.” However, if the analyst examines how an existing set of beliefs, norms, and practices comes under attack, undergoes delegitimation, or falls into disuse, to be replaced by new rules, forms, and scripts, we have a study of institutional change. Processes of creation are discussed here; other types of change processes are reviewed in later chapters.

1. Naturalistic Versus Agent-Based Accounts

As noted in Chapter 1, writing at the beginning of the 20th century, William Graham Sumner (1906) observed that although many institu- tions are “cressive,” evolving as a result of unintended, interdependent actions over long periods of time, others are “enacted,” intendedly designed by purposive actors. This distinction has recently been revived and renewed by Strang and Sine (2002), who distinguish between “naturalistic” and “agent-based” accounts of institutional construction. Naturalistic accounts treat institutionalization as a “natu- ral and undirected process” (Strang and Sine 2002: 502). Such views are embodied in the work of Schutz (1932/1967) and Berger and Luckmann (1967), who stress the unconscious ways in which activities evolve as multiple actors first engage with and attempt to make sense of their common situation and then develop responses that over time become habitualized, reciprocally reinforced and passed on to others as “the way we handle this type of issue.” Another type of naturalistic process is described by ecologists, such as Carroll and Hannan (1989), who interpret the increasing pervasiveness of an organization form—its higher “organizational density”—as evidence of its “taken-for- grantedness”: its institutionalization (see Chapter 6). In these accounts, institutions are not created by the purposeful actions of interest-based agents, but rather emerge from the collective sense-making and problem-solving behavior of actors confronting similar situations.

By contrast, analysts embracing an agent-based view stress the importance of identifying particular actors as causal agents, empha- sizing the extent to which intentionality and self-interest are at work. Following Stinchcombe’s early formulation giving heightened atten- tion to power (see Chapter 2), DiMaggio (1988) also emphasized the importance of “bringing agency back in” to accounts of institutional processes. He noted that studies of highly institutionalized organi- zations or organization fields can easily overlook the role of self- interest and power processes because opposing interests have been suppressed and dissenters silenced. The play of power is more visible during times of institutional change and, especially, institutional construction (DiMaggio 1991).

Put simply . . . institutionalization is a product of the political efforts of actors to accomplish their ends… [T]he success of an institutionalization project and the form that the resulting institu- tion takes depends on the relative power of the actors who sup- port, oppose, or otherwise strive to influence it… Central to this line of argument is an apparent paradox rooted in the two senses in which the term institutionalization is used. Institutionalization as an outcome places organizational structures and practices beyond the reach of interest and politics. By contrast, institutional-ization as a process is profoundly political and reflects the relative power of organized interests and the actors who mobilize around them. (DiMaggio 1988: 13)

Limits of Institutional Design

It is certainly the case that actors frequently work to create institu- tions that will reflect, protect, and advance their interests, that “parties often need institutions to help capture gains from cooperation” (Weingast 2002: 670). However, numerous considerations undermine the ability of actors to achieve their intended ends. Paul Pierson (2004) provides a useful synthesis and summary of the kinds of limitations that beset attempts to design institutions:

- “Specific institutional arrangements invariably have multiple effects” (p. 109), many of which are unexpected, unintended, and may be unwelcome.

- “Institutional designers may not act instrumentally” (p. 110), but be guided by norms of “appropriateness,” by fads, or by misguided attempts to apply ready-made solutions that do not fit current circumstances.

- “Institutional designers may have short time horizons” (p. 112), whereas the institutions they develop have long-term effects that frequently differ from those originally sought.

- The plans of institutional designers may lead to unexpected effects because the situations to which they apply have under- gone change.

- Institutional designs presume that actors and their interests will remain unchanged, whereas over time actors come and go and interests change.

Another general argument long made by organization theorists points to the erosion of the founders’ mission over time by an “organi- zational imperative” to protect and grow the organization, even at the sacrifice of its original objective. Beginning with the influential work of Michels (1915/1949) and extending through the work of Merton and Selznick up to the studies by Brint and Karabel (1991) and Kraatz, Ventreca, and Deng (2010), analysts point to ways in which environ- ment pressures can result in the transformation of organizational goals. (These and related studies are described below and in subsequent chapters dealing with organization and institutional change.)

Such concerns should make us mindful of the assumptions we make when assessing the role of agency, interest, and rationality in the design of institutions.

Institutional Entrepreneurs1

An important facet of the discourse surrounding institutional con- struction was initiated by Eisenstadt (1980) and Paul DiMaggio (1988) with their introduction of the concept of “institutional entrepre- neur.” Because it links such construction to the seminal early work of Schumpeter and also reenergizes the “structure-agency” debate, this concept has received extensive attention and elicited much debate and inquiry (Battilana and D’Aunno 2009; Ruef and Lounsbury 2007a).

Schumpeter (1926/1961) defined the “entrepreneurial function” as the creation of “new combinations” of existing resources, whether material, social, or symbolic. Usefully, Schumpeter emphasized func- tions and activities rather than personal characteristics, allowing for the possibility that the functions may be distributed across actors and recognizing that the entrepreneurial process does not “create” new resources, but combines existing resources in novel ways (Aldrich 2005; Becker and Knudsen 2009). Such a stance resonates with institu- tional views that stress that actors are embedded in existing contexts and operate with available materials.

A neglected aspect of the entrepreneurial function in building insti- tutions has been identified and elaborated by Fligstein (2001b), who examines the kinds of “social skills” required to induce cooperation among others with varying agendas and interests. Such individuals are able to focus attention on “evolving collective ends,” constructing shared meanings as common agendas are configured, and broker agreements among diverse individuals and interests (p. 113). These types of social skills may be as or more important than the technical skills commonly emphasized.

In order to clarify the conceptual terrain, I have proposed the fol- lowing distinctions (Scott 2010: 32–33):

- Organizational entrepreneurs are actors who pursue their objec- tives by founding a new enterprise—a new organization, but within an existing institutional mold. Such efforts entail the mobilization of resources and the assumption of risk for the value of the resources The efforts produce what Aldrich and Ruef (2006: 67) term a “reproducer organization.”

- Following Maguire, Hardy, and Lawrence (2004: 657), institutional entrepreneurship refers to “the activities of actors who have an inter- est in particular institutional arrangements and leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ”

I find it useful to differentiate between two subtypes of institu- tional entrepreneurs:

- Technical and organizational population–level institutional entrepre- neurs combine human and technical resources in novel ways to create new types of products, processes, or forms of organizing, giving rise to “innovative organizations” (Aldrich and Ruef 2006). To be successful, such entrepreneurs must devote much attention to gaining acceptance from wider audiences for their creations.

- Field-level institutional entrepreneurs create or significantly trans- form institutional frameworks of rules, norms, and/or belief systems either working within an existing organization field or creating frameworks for the construction of a new field.

The population and field levels are not the only ones at which insti- tutional construction occurs, as noted below, but they are among the more important for scholars examining institutional processes and organizations.

2. Accounts and Pillars

Whether a naturalistic or an agent-based approach is employed appears to vary, on first examination, by what types of elements— whether regulative, normative, or cultural-cognitive pillars—are invoked. Those examining regulative elements are more likely to be methodological individualists and assume that individuals function as agents, constructing rules and requirements by some kind of delibera- tive, strategic, or calculative process. Pros and cons are weighed, causes and effects evaluated and argued, and considered choices are made. Majorities or authorities rule. Such analysts would appear to lean toward an agent-based view. Analysts examining institutions made up of normative elements are more likely to posit a more naturalistic pro- cess, as moral imperatives evolve and obligatory expectations develop in the course of repeated interactions. Cultural-cognitive institutions seem to emerge from the operation of even more ephemeral, naturalis- tic processes. Particularly in early accounts, shared understandings, common meanings, and taken-for-granted truths seem to have no par- ents, no obvious sources, no obvious winners or losers.

Although there are differences in the processes associated with each pillar, these characterizations, on reflection, appear to be oversim- plified and can be misleading. Consider regulative rules. If they appear rational and transparent, this reflects the extent to which certain types of social settings and procedures have been constructed to be—are institutionalized to serve as—seats of collective authority or as forums variously constituted for decision making. A more comprehensive analysis of regulatory rule-making would examine the constitutive roots of the specific governance apparatus—how the forums developed, the rules evolved for decision making and for selecting participants— as well as all the backstage activities (the fodder of historical institu- tionalists) that enter into the creation of laws and legal rulings. Conversely, although norms often evolve through nonpurposeful interaction, they can also be rationally crafted. Professional bodies and trade associations act to create and amend their normative frameworks and standards via more conscious and deliberative processes, as docu- mented below. As with regulatory authorities, some social groups are endowed with special prerogatives allowing them to exercise moral leadership in selected arenas, whether they are environmental scien- tists dealing with global warming or medical scientists dealing with the control of contagious diseases. Cognitive elements also result from both more and less rational choice processes; they may evolve from inchoate collective interactions but they can also be consciously designed and disseminated by highly institutionalized cultural author- ities (Scott 2008b). Folkways are produced by the former; scientific truths and laws, by the latter.

In sum, it appears that the two accounts of institutional construc- tion should best be regarded as the endpoints of a continuum along which institutional work takes place. Most “rational agents” do not fully understand their situation or the consequences that follow from the alternatives they select, and most “naturalistic” actors are moti- vated to advance their own interests whether or not they can articulate the reasons for their choices (Emirbayer and Mische 1998). Institutions have many fathers and mothers, only some of which recognize and acknowledge their parental role.

3. Types of Agents

DiMaggio and Powell (1983: 147) astutely observe that the nation- state and the professions “have become the great rationalizers of the second half of the twentieth century,” but other types of actors also play important roles. As defined above, institutional entrepreneurs are individuals or organizations who participate in the creation of new types of organizations or new industries, tasks that require marshalling new technologies, designing new organizational forms and routines, creating new supply chains and markets, and gaining cognitive, norma- tive, and regulative legitimacy. Clearly, we are not talking about a sin- gle actor, but a variety of roles and functions distributed across diverse players.

I briefly describe some of the major categories of institutional agents currently at work.

The Nation-State

From some perspectives, the state is simply another organizational actor: a bureaucratically organized administrative structure empow- ered to govern a geographically delimited territory. However, such a view is limited and misleading. In our own time, and since the dawn of the modern era, the nation-state has been allocated—is constituted in such a way as to exercise—special powers and prerogatives (Krasner 1993). As Streeck and Schmitter (1985: 20) pointed out, the state is not simply another actor in the environment of an organization: Its “abil- ity to rely on legitimate coercion” make it a quite distinctive type of actor. All organizations are correctly viewed as “governance structures,” but the state is set apart. Lindblom (1977: 21) succinctly concludes:

“The special character of government as an organization is simply . . . that governments exercise authority over other organizations.”

In terms of institutional construction, states (in collaboration with legal professionals) possess extraordinary constitutive powers to define the nature, capacity, and rights enjoyed by political and eco- nomic actors, including collective actors. For example, during the past three centuries, states have worked to shape the powers and rights of the joint stock, limited liability corporate actor that has long since become the preferred form for organizing economic activity (see Coleman 1974; 1990; Micklethwait and Wooldridge 2003; Seavoy 1982). Such activity is ongoing. Only recently, the U.S. Supreme Court extended the free speech rights of corporations and unions by prohib- iting any restrictions on their independent expenditures in support of issues or candidates.

More generally, Campbell and Lindberg (1990) detail the ways in which, by defining and enforcing property rights, the state influences the economic behavior of organizations. Property rights are “the rules that determine the conditions of ownership and control of the means of production” (p. 635), including labor laws defining the power of work- ers to organize, antitrust laws that limit ties between competitors, and patent laws that limit access to new technologies.

The state provides the legal framework within which contracts are written and enforced. . . . The state’s influence, quite apart from sporadic interventions, is always present in the economy insofar as it provides an institutional and legal framework that influences the selection of different governance regimes and thereby perma- nently shapes the economy. (Campbell and Lindberg 1990: 637)

Even the regulatory powers of the state can lead to the creation of new institutional forms. Fligstein (1990) underlined the role of antitrust legislation, including the Sherman Act of 1890, which prevented the development of the cartel-like forms that emerged in Europe at this time—unlike the United States, the German (as well as other European) states emphasized “the benefits of industrial cooperation” (Chandler 1990: 395)—and the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950, which encouraged diversification (supported by the multidivisional corporate form) as a growth strategy for U.S. corporations after World War II (see Chapters 7 and 8).

States also exert highly significant effects not only on individual firm structures and behaviors, but also on the structuration of organiza- tion fields. Baron, Dobbin, and Jennings (1986) provide a historical account of the powers of the state to shape industry (field) and firm structure in their study of the evolution of modern personnel systems in the United States. The high water mark of state influence occurred in connection with the mobilization for World War II, when the federal government intervened to stabilize employment. Agencies such as the War Production Board, the War Labor Board, and the War Manpower Commission “engaged in unprecedented government manipulation of labor markets, union activities, and personnel practices. These interven- tions . . . fueled the development of bureaucratic controls by creating models of employment and incentives to formalize and expand person- nel functions” (Baron et al. 1986: 369). In short, the pressures created were cultural-cognitive and normative, inducing conformity among professional managers as well as regulative controls involving coercion. Later chapters detail other ways in which states influence the struc-ture and behavior of firms and fields.

Corporations and Other Business Organizations

In capitalist economies, in particular, business firms exert enor- mous power over the organization and mobilization of economic resources. They create hierarchical frameworks to exert direct coercive and regulatory authority over their paid personnel, but also form alli- ances, enter into networks, negotiate contracts, and design and rede- sign a variety of governance frameworks to oversee their enterprise (Child 2005; Scott and Davis 2007). At the firm level, they exercise control over the allocation of assets at their disposal; collectively, at the industry level, they work both competitively and cooperatively to influence policies and programs that affect their welfare.

Fligstein (1990, 1991) stressed the role of corporate elites who are in a position to negotiate—with their competitors and within constraints imposed by the state—an institutional framework working to curb cut- throat competition and allow multiple firms to operate in a given field or arena, albeit with differing advantages. The ability of elites to man- age these negotiations depends “on the resources that organizations command and the types of network and dependency relations the organization has to other organizations” (Fligstein 1991: 314).

Elite organizations can also mobilize politically to advance their collective interests (Cawson 1985). Vogus and Davis (2005) described the efforts of corporate elites to defend themselves against state legisla- tion favorable to takeover attempts. The better organized the local corporate elite—assessed in terms of number of board interlocks—the more likely was the state to adopt management-friendly legislation regulating hostile takeovers.

During the second half of the 20th century, many firms reorganized to operate as multinational corporations to produce goods and services for a global market through facilities located around the world. This development, as Gereffi (2005:163) points out, has moved the global economy from a “shallow integration” manifested largely through international exchanges of money and materials to a “deep integra- tion” involving “the production of goods and services in cross-border value-adding activities that redefine the kinds of production processes contained within national boundaries.” Supply and value chains are devised linking raw materials and final products in ever-changing combinations of firms as supply sources fail or demand changes. These flexible networks represent important new types of institutional arrangements.

The Professions

In modern societies, professional occupations have come to play a unique and distinctive role. They have displaced the seers and wise men and women of earlier times to serve in a variety of capacities as institutional agents. We emphasize here their role as creators of new institutional frameworks. Employing the pillars framework, we observe that different types of professionals make use of differing combinations of elements (see Scott 2008b). Some professionals operate primarily within the cultural-cognitive sphere by creating new conceptual systems: “Their primary weapons are ideas. They exercise control by defining reality—by devising ontological frameworks, proposing distinctions, creating typifications, and fabricating principles or guidelines for action” (Scott and Backman 1990: 29).

The knowledge systems constructed vary greatly in their content and in the extent of their empirical grounding, with physical and bio- logical scientists working at the more empirically constrained end and philosophers and literary critics operating in less confined arenas. Strang and Meyer (1993: 492) stress the importance of the role of theo- rization: “the development and specification of abstract categories, and the formulation of patterned relationships such as chains of cause and effect” in the construction and diffusion of new institutions.

The types of professionals who emphasize the construction of nor- mative frameworks include theologians and ethicists, many legal schol- ars, and accountants. However, in addition to these specialists, a great many other professional groups work within their associations to create and promulgate “standards” in their areas of expertise, which range from the threading of screws to the education of children and the control of AIDS (Brunsson and Jacobsson 2000).

Other professionals, including many legal experts, military offi- cers, and managers, exercise substantial influence on the construction of regulatory frameworks. Lawyers in many countries (especially the United States) have a near monopoly on positions within policy- setting and state regulatory bodies: authorities empowered to create and enforce new kinds of institutional regimes. Managerial profes- sionals increasingly are in a position to craft new governance struc- tures for overseeing their enterprises. Institutional economists are ready to supply design criteria to executives seeking to craft more effective and efficient governance systems to reduce production and transaction costs.

Students of occupations have long claimed that, although their compositional boundaries are somewhat unclear and shifting over time, the professions, as a category, have been guided by normative codes that emphasize disinterested service, embracing a “social trust- eeship” model (Brint 1994; Freidson 2001). Similarly, Meyer (1996) argues that the professions often act as disinterested “others” rather than self-interested actors, attempting to speak, for example, for the protection of the environment or for social justice. However, there are disturbing signs that these codes and logics are weakening in part because of a shift in generalized beliefs about the relative value and morality of public service and private gain, and as more professionals place emphasis on their “technical expertise” as validated by the market (Brint 1994; Scott 2008b).

Associations

Joining nation-states and professions as important classes of insti- tutional actors exercising authority in cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative domains are an increasingly diverse array of associations operating at national and international levels. In general, associa- tions are organizations established to more effectively pursue the interests of their members. Many associations take the form of “meta- organizations”: organizations whose members are themselves organi- zations (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008). Many associations operate by promulgating standards—sometimes regarding the behavior of their own members (e.g., business associations) but often attempting to affect the behavior of wider publics (e.g., professional associations). Associations vary significantly across countries and over time in their ability to establish and enforce standards of practice (Tate 2001). Their efforts are historically situated and follow distinctive trajectories influ- enced in particular by the closeness of their connection to the state. Those in liberal regimes are more likely to pursue voluntary and cooperative approaches, whereas those working within more coordinated econ- omies are more likely to seek and receive the backing of the coercive power of the state (Hall and Soskice, 2001b).

As globalization proceeds apace, associations of all sorts now oper- ate at the transnational level, organized as international nongovern- mental organizations (INGOs). Such organizations existed throughout the 20th century, but have grown rapidly in numbers and influence since World War II (Boli and Thomas 1997; Smith 2005). How do INGOs obtain and exercise their influence? Boli and Thomas (1997; 1999) point out that, at the present time, they do not presume to displace or replace nation-states, and, unlike states, they cannot make or enforce law. Unlike global corporations, they are not able to exercise coercive power and lack economic resources to employ as sanctions. Rather, “INGOs are more or less authoritative transnational bodies employing limited resources to make rules, set standards, propagate principles, and broadly represent ‘humanity’ vis-à-vis states and other actors” (Boli and Thomas 1997: 172; see also Brunsson and Jacobsson 2000).

While they lack coercive power or regulative authority, in an era where neo-liberal ideologies limit the sphere within which nation- states may exercise control, systems of “private regulation,” relying on mutual surveillance and voluntary compliance provide valuable alter- native regulatory regimes. Bartley (2003) details efforts between 1990 and 2000 involving two contrasting industry associations, forest products and apparel manufacturing, which have worked with the assistance of INGOs to develop and enforce environmental and labor standards within their respective industries. Numerous nation-states, acting both directly and indirectly, have supported such arrangements, recognizing their own inability to take action under current political- economic conditions.

Social Movements

Whereas earlier theory and research emphasized the actions of established and authoritative actors, such as professionals or state offi- cials, engaged in institutional design or redesign projects, a wave of scholars drawing from social movement ideas and arguments have recently significantly reshaped the narrative to include new kinds of players employing different techniques and tools (Davis, McAdam, Scott, and Zald 2005). Whereas established authorities rely on coercive, normative, and memetic processes to diffuse their models and frame- works creating isomorphic structures, movement actors employ issue- framing, mobilization, and contestation to champion new ways of organizing. Social movement theory came into its own during the 1960s, a time of extraordinary social upheaval in the Western democra- cies, bringing together ideas and arguments from political science and sociology to examine the sources and mechanisms of bottom-up social and institutional change. Also, as Schneiberg and Lounsbury (2008) point out, although movement scholars adopt some of the premises of those who study institutional entrepreneurs—for example, their emphasis on agency and deliberate, strategic action—a social move- ment approach is likely to be more structural, stressing constraints and openings (“opportunity structures”) in existing political structures and the importance of collective mobilization around a common concern.

Two types of approaches have evolved: (1) studies that treat move- ments as “forces against institutions, that is, forces operating outside established channels to assert new visions and disrupt or directly contest existing arrangements,” and (2) studies that examine movements oper- ating within established institutional systems, working to exploit exist- ing differences and contradictions and introduce reforms (Schneiberg and Lounsbury 2008: 652). A good example of a study of the first type is provided by Clemens (1993; 1997). Clemens points out that sup- pressed interests are often denied conventional modes of exercising voice or influence and, as a consequence, are forced to employ uncon- ventional approaches. She examines the emergence of the women’s movement in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. Prohibited from the ballot box and from mainstream electoral politics, activist women borrowed from the tactics employed by disreputable lobbyists, only to perfect them into a repertoire of actions now used by all interest groups. They embraced conventional organizing forms (e.g., women’s clubs), but used them to advance the political education of their members, mobilize public opinion, gain procedural mastery of the legislative process, and devise ways to intervene in shaping policy and hold political officers accountable for their votes and decisions.

The second type, movements developing within institutionalized systems, is well illustrated by the research of Scully and Creed (2005), who examined the ways in which a subset of existing employees were able to secure the adoption of gay-friendly policies by organizations. In their work, they emphasize the central role played by the construc- tion of social identities—the processes by which workers began to recognize/construct a set of shared identities allowing them to work within and across organizations to, first, legitimate their identity and, then, create and diffuse repertories of action to instigate and gain support for new policies. Researchers noted that “agents talked of innovation but were startlingly alike in their approaches and out- comes” (p. 311), having informally shared ideas and tactics. “The social construction of a collective identity involves defining the field of action that the actors inhabit, as well as their interests, ends, and means” (p. 312).

Marginal Players

Network theorists stress the importance of marginality to fostering innovation and learning processes. Those who locate gaps or missing connections in social networks—“structural holes” (Burt 1992)—or who are associated with persons or organizations unlike themselves— forming “weak ties” (Granovetter 1973)—are likely to garner influence and be exposed to ideas different from their own. Just as the locations where sea water meets fresh water are particularly supportive of var- ied forms of marine life, so the areas of overlap and confluence between institutional spheres generate rich possibilities for new forms. Morrill (forthcoming) depicted the emergence of a new organization field staffed by new types of actors at the boundary where conventional legal structures overlap with social welfare forms. The field of alterna- tive dispute resolution emerged between 1965 and 1995 in response to a growing number of minor disputes that were clogging the law courts. A community mediation model, championed by the social work com- munity, and a multidoor-courthouse model, supported by lawyers, competed for the jurisdiction of this interstitial arena. Morrill detailed the processes by which new roles and practices were created (innova- tion), legitimation and resources were acquired from players in the existing fields (mobilization), and a stable uncontested institutional settlement achieved (structuration). Morrill concluded:

In the interstices created by overlapping resource networks across organizational fields, rules, identities, and conventional practices are loosened from their taken-for-granted moorings and alterna- tive practices can emerge, particularly in the face of perceived institutional failure.

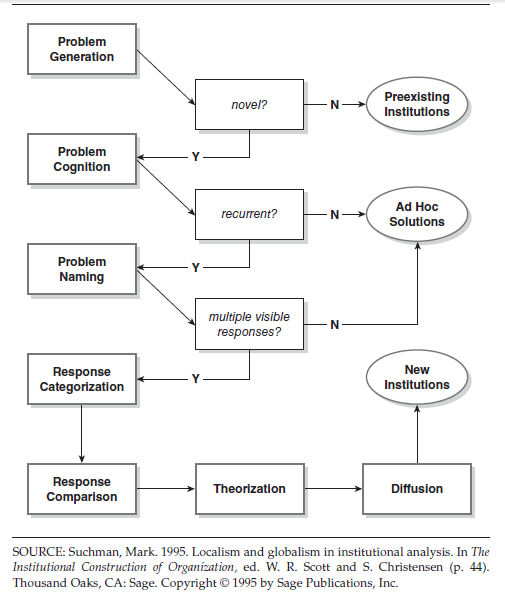

4. Demand- and Supply-Side Explanations

Mark Suchman (1995a) provides an illuminating general discus- sion of conditions giving rise to new institutional arrangements. He suggests that the impetus for institutional creation is the development, recognition, and naming of a recurrent problem to which no preexist- ing institution provides a satisfactory repertoire of responses (see Figure 5.1). These cognitive processes can be viewed as giving rise to collective sense-making activities, as elucidated by Weick (1995), as actors attempt to interpret and diagnosis the problem and, subsequently, propose what are, at the outset, various ad hoc solutions. Once these responses have been “generalized into solutions,” it may be possible for the participants to engage in “a more thoroughgoing ‘theorization’ of the situation—in other words, to formulate general accounts of how the system works and, in particular, of which solutions are appropriate in which contexts” (Suchman 1995a: 43). Solutions generated in one context may then diffuse to other situations regarded as similar. Note the extent to which Suchman’s discussion maps onto and builds from Berger and Luckmann’s (1967) general formulation of institutionaliza- tion, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3.

Figure 5.1 A Multistage Model of Institutionalization

The foregoing description is meant to be sufficiently abstract to be applicable to any level of analysis—from the organizational subsystem to the world system. Suchman (1995a: 41) proposed that the question of where institutions arise—at what level—is determined by “where in the social structure particular shared understandings arise.” That is, this question is to be settled empirically by observing the locus of the social processes at work. At a broader level, Suchman’s general model embodies a “demand-side” argument: Institutions are crafted by actors in response to recurrent problems for which no existing “off-the-shelf” solutions are available.

A contrasting view of institutional construction offered by John Meyer (1994) is that institutional creation can also be driven by “supply- side” processes. His arguments are developed primarily at the world system level, but are applicable to other levels. He suggests, as noted earlier, that certain types of actors—particularly those in the sciences and professions—occupy institutionalized roles that enable and encourage them to devise and promote new schemas, rules, models, routines, and artifacts. They see themselves as engaged in the great project of rationalization, whereby more and more arenas of social life are brought under the “rubric of ideologies that claim universal applicability” (p. 42). The adoption of these generalized principles and procedures is promoted as evidence of “modernization,” irrespec- tive of whether local circumstances warrant or local actors “need” or want these developments. At the international and societal levels, general rules and principles are promulgated by professional associa- tions and a wide range of NGOs. At the level of the organization field, organizational population, and individual organization, the carriers and promoters include foundations, management schools, account- ing and auditing firms, and consulting companies (see DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Sahlin and Wedlin 2008). These purveyors of solutions must often begin their work by convincing potential adopters that they have a problem.

Source: Scott Richard (2013), Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, SAGE Publications, Inc; Fourth edition.