Philosophy of the movement started by Diogenes of Sinope (4th century BC) and possibly influenced by Antisthenes, a contemporary and disciple of Socrates (469-399 BC).

The movement lasted intermittently for some 800 years or more, flourishing mainly in its first two centuries and again under the early Roman Empire (first two centuries AD).

The Cynics were akin to and in some ways forerunners of the Stoics, but they confined themselves to ethics and never gained the respectability of the Stoics.

Like the Stoics they advocated self-sufficiency, and the avoidance of emotional entanglements and slavery to desire, but unlike stoicism they rejected social conventions and constraints as unnatural. The name ‘Cynics’ means ‘doggy ones’, perhaps because of their uninhibited habits (though other etymologies have been suggested).

Source:

D R Dudley, A History of Cynicism (1937)

Origin of the Cynic name

The name Cynic derives from Ancient Greek κυνικός (kynikos) ‘dog-like’, and κύων (kyôn) ‘dog’ (genitive: kynos).[4] One explanation offered in ancient times for why the Cynics were called “dogs” was because the first Cynic, Antisthenes, taught in the Cynosarges gymnasium at Athens.[5] The word cynosarges means the “place of the white dog”. It seems certain, however, that the word dog was also thrown at the first Cynics as an insult for their shameless rejection of conventional manners, and their decision to live on the streets. Diogenes, in particular, was referred to as the “Dog”,[6] a distinction he seems to have revelled in, stating that “other dogs bite their enemies, I bite my friends to save them.”[7] Later Cynics also sought to turn the word to their advantage, as a later commentator explained:

There are four reasons why the Cynics are so named. First because of the indifference of their way of life, for they make a cult of indifference and, like dogs, eat and make love in public, go barefoot, and sleep in tubs and at crossroads. The second reason is that the dog is a shameless animal, and they make a cult of shamelessness, not as being beneath modesty, but as superior to it. The third reason is that the dog is a good guard, and they guard the tenets of their philosophy. The fourth reason is that the dog is a discriminating animal which can distinguish between its friends and enemies. So do they recognize as friends those who are suited to philosophy, and receive them kindly, while those unfitted they drive away, like dogs, by barking at them.[8]

Philosophy

Cynicism is one of the most striking of all the Hellenistic philosophies.[9] It claimed to offer people the possibility of happiness and freedom from suffering in an age of uncertainty. Although there was never an official Cynic doctrine, the fundamental principles of Cynicism can be summarized as follows:[10][11][12]

- The goal of life is eudaimonia and mental clarity or lucidity (ἁτυφια) – literally “freedom from smoke (τύφος)” which signified false belief, mindlessness, folly, and conceit.

- Eudaimonia is achieved by living in accord with Nature as understood by human reason.

- Arrogance (τύφος) is caused by false judgments of value, which cause negative emotions, unnatural desires, and a vicious character.

- Eudaimonia, or human flourishing, depends on self-sufficiency (αὐτάρκεια), equanimity, arete, love of humanity, parrhesia, and indifference to the vicissitudes of life (adiaphora ἁδιαφορία).[12]

- One progresses towards flourishing and clarity through ascetic practices (ἄσκησις) which help one become free from influences – such as wealth, fame, and power – that have no value in Nature. Instead they promoted living a life of ponos. For the Cynics, this did not seem to mean actual physical work. Diogenes of Sinope, for example, lived by begging, not by doing manual labor. Rather, it means deliberately choosing a hard life — for instance, wearing only that thin cloak and going barefoot in winter.[13]

- A Cynic practices shamelessness or impudence (Αναιδεια) and defaces the nomos of society; the laws, customs, and social conventions which people take for granted.

The Cynics adopted Heracles, shown here in this gilded bronze statue from the second century AD, as their patron hero.[14][15]

Thus a Cynic has no property and rejects all conventional values of money, fame, power and reputation.[10] A life lived according to nature requires only the bare necessities required for existence, and one can become free by unshackling oneself from any needs which are the result of convention.[16] The Cynics adopted Heracles as their hero, as epitomizing the ideal Cynic.[14] Heracles “was he who brought Cerberus, the hound of Hades, from the underworld, a point of special appeal to the dog-man, Diogenes.”[15] According to Lucian, “Cerberus and Cynic are surely related through the dog.”[17]

The Cynic way of life required continuous training, not just in exercising judgments and mental impressions, but a physical training as well:

[Diogenes] used to say, that there were two kinds of exercise: that, namely, of the mind and that of the body; and that the latter of these created in the mind such quick and agile impressions at the time of its performance, as very much facilitated the practice of virtue; but that one was imperfect without the other, since the health and vigour necessary for the practice of what is good, depend equally on both mind and body.[18]

None of this meant that a Cynic would retreat from society. Cynics were in fact to live in the full glare of the public’s gaze and be quite indifferent in the face of any insults which might result from their unconventional behaviour.[10] The Cynics are said to have invented the idea of cosmopolitanism: when he was asked where he came from, Diogenes replied that he was “a citizen of the world, (kosmopolitês).”[19]

The ideal Cynic would evangelise; as the watchdog of humanity, they thought it their duty to hound people about the error of their ways.[10] The example of the Cynic’s life (and the use of the Cynic’s biting satire) would dig up and expose the pretensions which lay at the root of everyday conventions.[10]

Although Cynicism concentrated primarily on ethics, some Cynics, such as Monimus, addressed epistemology with regard to tuphos (τῦφος) expressing skeptical views.

Cynic philosophy had a major impact on the Hellenistic world, ultimately becoming an important influence for Stoicism. The Stoic Apollodorus, writing in the 2nd century BC, stated that “Cynicism is the short path to virtue.”[20]

History of Cynicism

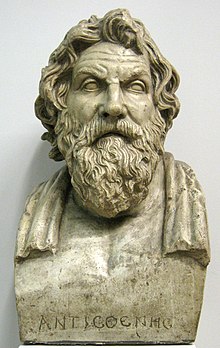

Bust of Antisthenes

The classical Greek and Roman Cynics regarded virtue as the only necessity for happiness, and saw virtue as entirely sufficient for attaining it. Classical Cynics followed this philosophy to the extent of neglecting everything not furthering their perfection of virtue and attainment of happiness, thus, the title of Cynic, derived from the Greek word κύων (meaning “dog”) because they allegedly neglected society, hygiene, family, money, etc., in a manner reminiscent of dogs. They sought to free themselves from conventions; become self-sufficient; and live only in accordance with nature. They rejected any conventional notions of happiness involving money, power, and fame, to lead entirely virtuous, and thus happy, lives.[21]

The ancient Cynics rejected conventional social values, and would criticise the types of behaviours, such as greed, which they viewed as causing suffering. Emphasis on this aspect of their teachings led, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries,[22] to the modern understanding of cynicism as “an attitude of scornful or jaded negativity, especially a general distrust of the integrity or professed motives of others.”[23] This modern definition of cynicism is in marked contrast to the ancient philosophy, which emphasized “virtue and moral freedom in liberation from desire.”[24]

Influences

Various philosophers, such as the Pythagoreans, had advocated simple living in the centuries preceding the Cynics. In the early 6th century BC, Anacharsis, a Scythian sage, had combined plain living together with criticisms of Greek customs in a manner which would become standard among the Cynics.[25] Perhaps of importance were tales of Indian philosophers, known as gymnosophists, who had adopted a strict asceticism. By the 5th century BC, the sophists had begun a process of questioning many aspects of Greek society such as religion, law and ethics. However, the most immediate influence for the Cynic school was Socrates. Although he was not an ascetic, he did profess a love of virtue and an indifference to wealth,[26] together with a disdain for general opinion.[27] These aspects of Socrates’ thought, which formed only a minor part of Plato’s philosophy, became the central inspiration for another of Socrates’ pupils, Antisthenes.

Symbolisms

Cynics were often recognized in the ancient world by their apparel—an old cloak and a staff. The cloak came as an allusion to Socrates and his manner of dress, while the staff was to the club of Heracles. These items became so symbolic of the Cynic vocation that ancient writers accosted those who thought that donning the Cynic garb would make them suited to the philosophy.[28]

In the social evolution from the archaic age to the classical, the public ceased carrying weapons into the poleis. Originally it was expected that one carried a sword while in the city; However, a transition to spears, and then to staffs occurred until wearing any weapon in the city became a foolish old custom.[29] Thus, the very act of carrying a staff was slightly taboo itself. According to modern theorists, the symbol of the staff was one which both functions as a tool to signal the user’s dissociation from physical labour, that is, as a display of conspicuous leisure, and at the same time it also has an association with sport and typically plays a part in hunting and sports clothing. Thus, it displays active and warlike qualities, rather than being a symbol of a weak man’s need to support himself.[30][31] The staff itself became a message of how the Cynic was free through its possible interpretation as an item of leisure, but, just as equivalent, was its message of strength – a virtue held in abundance by the Cynic philosopher.

Antisthenes

The story of Cynicism traditionally begins with Antisthenes (c. 445–365 BC),[32][33] who was an older contemporary of Plato and a pupil of Socrates. About 25 years his junior, Antisthenes was one of the most important of Socrates’ disciples.[34] Although later classical authors had little doubt about labelling him as the founder of Cynicism,[35] his philosophical views seem to be more complex than the later simplicities of pure Cynicism. In the list of works ascribed to Antisthenes by Diogenes Laërtius,[36] writings on language, dialogue and literature far outnumber those on ethics or politics,[37] although they may reflect how his philosophical interests changed with time.[38] It is certainly true that Antisthenes preached a life of poverty:

I have enough to eat till my hunger is stayed, to drink till my thirst is sated; to clothe myself as well; and out of doors not [even] Callias there, with all his riches, is more safe than I from shivering; and when I find myself indoors, what warmer shirting do I need than my bare walls?

Everything is very open and very clear explanation of issues. was truly information. Your website is very useful. Thanks for sharing.

Spot on with this write-up, I actually think this website requirements considerably more consideration. I’ll oftimes be once again to learn additional, thank you for that information.

I really like and appreciate your blog post.Really thank you! Awesome.