Despite a growing body of literature, organizational discourse remains, at best, a nascent field in organization studies. While there has been much work done, there is still little agreement on the theoretical and methodological foundations of the field. At the same time, it is an area that has great potential for exploring power in organizations. A discourse analytic approach combines an explanation for the mechanisms through which reality is constituted with an explicit sensitivity to power (at least if we adopt a more critical perspective). The developing discourse analytic in organization studies therefore remains one of the most interesting developments in terms of understanding power in organizations, although much work remains to be done both in terms of developing the methodology and in terms of extending the empirical topics on which it has been applied.

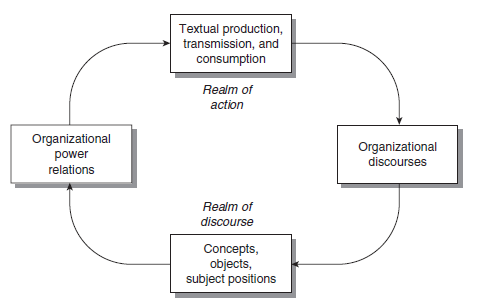

Figure 10.2 The mutually constitutive relation between discourse and power (adapted from Hardy and Phillips 2004)

Our view of the relation between discourse and power in organizations is shown in Figure 10.2. In the figure, the complex interaction between discourses and sys- tems of power is shown in the mutually constitutive links between power relations and discourse. But these relations are not direct. The distribution of power funda- mentally shapes the way texts are produced and disseminated; who can produce what texts in what way is conditioned by patterns of resources, legitimacy and the like. The nature of the texts produced both maintains and changes the discourse, leading to either stability or change. The collection of texts determines the system of concepts, objects, and subject positions that are constituted by discourse at a particular moment. The system of concepts, objects, and subject positions consti- tutes the relations of power that characterize the organization – and we have come full circle. This complex mutually constitutive relationship lies at the heart of the discourse analytic of power we have been exploring in this chapter.

The critical power of discourse analysis lies in the tensions between discourse and the linguistic and textual elements of which it is composed, and between discourse and the social world it constitutes. It is this combination that allows the connection to be made between micro-practices in organizations and the intra- and inter-organizational discourses that constitute the building blocks of organizations. While this is the real strength of discourse analysis it is also the source of the great- est challenge. Discourse analytic studies in the main focus either on the nature of the texts that make up the discourse, with only a limited discussion of the relation between the discourse and the social world it helps to constitute, or on the relation between the discourse and the social world while only dealing with the texts that make up the discourse in a cursory way. There is, therefore, a tremendous opportu- nity to expand and develop discourse analysis as a method by moving towards a more balanced approach to connecting social context to micro-practices through discourse analysis. Creating more balance between the three elements of discourse analysis will provide much more analytic power but also demands significant inno- vation in methods of data collection, analysis and theoretical discussion.

Organizational discourse analysis faces an additional challenge. It has, as we mentioned above, been increasingly criticized for its tendency to adopt ‘extreme forms of social constructivism’ that limit ‘the value of one prominent tendency within current research on organizational discourse for organizational studies’ (Fairclough 2005: 915). Reed (2004: 413) has described this tendency as the ‘anti- realist, subjectivist, relativist, and ideationalist’ tendency in discourse analysis. The postmodern tendency in discourse analysis grows largely out of the Foucauldian roots of many of the ideas that make it up. Fairclough (2005), in his recent critique, suggests that discourse analysis is losing theoretical traction due to its loss of a dualistic epistemology focusing on the relations between agency and structure. In other words, by seeing organizations as only discourse, it is missing the opportu- nity to deal with agency due to an overemphasis on structure. Discourse theory’s brief history offers an opportunity for it to turn to sociological formulations that predate the current enthusiasm for discourse analysis and which do display a more sophisticated grasp of the relation of agency and structure.

Reed (2004) and Fairclough (2005) recommend the continued development of a critical realist approach to discourse analysis (see also Chouliaraki and Fairclough (1999)). A critical realist approach to discourse analysis begins with the premise that there is a difference between the world as it exists and our knowledge of it, which it maintains as a critical distinction. From this perspective the social world comes prestructured. Furthermore:

This prestructuring process, and the material conditions and social structures that it reproduces, cannot be collapsed into language or discourse. If they are so collapsed or conflated, then the ‘generative power’ inherent in social structures cannot be accessed or explained because it remains imprisoned within its ‘discursive moment’ – within the linguistic and textual forms through which it is communicated and represented. (Reed 2004: 415)

In other words, critics are calling for recognition of how transcendent elements of structure act in and through agency to structure political performance, as we shall investigate in the next chapter. The result of neglecting structural factors is a loss of analytic power. Discourse analysis, from this perspective, needs to resist the tempta- tion to conflate ontology and epistemology in order to retain its explanatory power.

How this particular discussion will work itself out remains to be seen. What is clear is that discourse analysis provides an important methodology for investigat- ing the dynamics of power and politics that are intrinsic to organizations. As we said in Chapter 1, power is to organizations as oxygen is to breathing, and the study of power needs to become just as intrinsic to the study of organizations. Discourse analysis, and particularly critical discourse analysis, provides one important oppor- tunity for further thinking and research on power in organizations.

Whereas organization theory may have been said to begin with the virtually mute body – think of Taylor’s Schmidt, the dumb Pennsylvanian Dutchman – it rapidly moved to the soul and the mind. In discourse analysis it takes the mind out of the body and into discourse. The mind materializes in language. Organizations teem with texts, discourses, and language. The everyday discourse and rhetoric of organizational life comes to the fore as the real stuff of analysis. It is in these that power will be found, in the ways of categorizing, constituting and conducting everyday sense. With discourse analysis, organization theory finally catches up with the fact that organizational management – and resistance – are largely done dis- cursively. There is no need to construct elaborate research instruments because there is all the complexity that one could desire in the mundane things of everyday organizational life.

Source: Clegg Stewart, Courpasson David, Phillips Nelson X. (2006), Power and Organizations, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1st edition.