We begin this chapter with the most primitive of all economic situations—the case where two companies make the same product ( with the same quality) and thus are forced to compete on price. We see how this simple situation escalates into price wars, then differentiated markets, then full-line producers, and then niche strategies, as competitors try to avoid the brutality of price wars. A sophisticated movement toward offering progressively higher customer value evolves. Like the force of gravity, the overall process of moves and countermoves tends to draw the industry back toward a price-competitive market after all the firms focus on imitating or outmaneuvering earlier moves. At some point everyone must move toward high quality and low cost to survive, and many firms offer the same range of product variety. Thus, the dynamics of competitive interaction cause product price and quality to cease to be opportunities for gaining advantage over competitors.

The individual players might be better off if they didn’t escalate the competition toward this situation. But the dynamics of their interaction force them along this path. If one of them were to drop out of the competition, the other would gain a temporary advantage. Each one cannot trust the other to de-escalate the conflict. This course is set in motion the minute the two players step into the arena of competing on price and quality.

We have observed during our research that firms interact competitively at each step of the way so as to escalate the conflict. This series of dynamic strategic interactions defines each step or level of competition within the cost (and price)-quality arena. We will observe each dynamic strategic interaction between players, looking at how it was caused by the previous dynamic strategic interaction and at how it leads to the next level of interaction. Overall, each step moves the industry up the “escalation ladder” toward a situation in which cost and quality are no longer a source of competitive advantage.

1. What Is Quality?

When we discuss quality here, we are referring to “perceived quality” of consumers. This can sometimes be very close to more concrete measures of quality (all of which are defined by consumers), but for some products consumers just don’t take the time to carefully assess quality, particularly for products that are low investment. Some consumers may be relatively unconcerned about costs for a product for which quality is the fundamental concern or a product such as a tube of toothpaste for which the cost is small enough not to matter much. Differences in customer perceptions can distort the broader view of price and quality presented here. Perceived quality also changes over time as customer preferences shift. A concern with automobile luxury shifts to a concern with gas mileage during the oil-strapped 1970s and then becomes an obsession with safety in the 1980s and 1990s.

From a marketing standpoint such broad approximations leave much to be desired. From an economic viewpoint the approximation of referring to “quality” as a clearly defined characteristic is one that is taken as a given in most models. We assume that there is a general standard of quality in an industry and that consumers are concerned about both price and quality. At the level of analyzing an individual company or industry, on the other hand, differences in perception of quality can be key and should be given careful consideration.

What is even more important is that these differences in the perception of quality and changes in the view of quality can be put to good use by companies searching for advantages. These quality perceptions change, and differences can provide key points of leverage in influencing the dynamic process of competition. As we will discuss in considering stakeholder satisfaction and strategic soothsaying in Part III, keeping in touch with emerging needs of customers and identifying new ways to meet those needs or emerging needs are essential strategies in hypercompetitive markets.

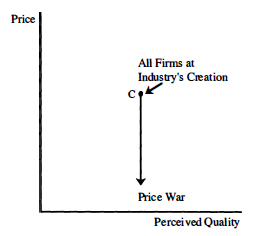

2. The First Dynamic Strategic Interaction: Price Wars

Unlike some other longer-lasting competitive moves, price changes can be very rapidly imitated, leading to all-out price wars. These conflicts can be particularly intense if the two firms have different costs, making it easier for one of them to cut prices. This encourages firms to compete by seeking cost reductions. Thus, price wars result when quality is not a factor. In Figure 1-1, if all firms are at point C, price moves downward. Price wars are not so simple, however. There are, for example, some interesting strategies for fighting price wars, which we consider below.

ALL-OUT WAR: TYLENOL’S HEADACHE

Typically a price war looks like the situation that occurred when Datril took on Tylenol in the pain reliever market. Datril offered the same- formula medicine for a lower price, capturing half of Tylenol’s sales in test markets in 1975. But Tylenol responded aggressively by lowering its price and launching its first ad campaign. Tylenol, which had as much as 37 percent of the analgesic market at one time, could fight with lower prices because of its economies of scale. As a result, Datril ended up with less than 1 percent of the market.5 But the battle was not without damage. In the process Tylenol gave up millions in profits.

FIGURE 1-1

WHEN QUALITY ISN’T A FACTOR

However, less aggressive alternatives are available. Competitors can use restraint, hidden price wars, and phantom price wars to avoid a head-to- head confrontation on prices.

RESTRAINT

In purely competitive markets price should fall to the marginal cost of the lowest-cost producer, who would normally be expected to expand to capture market share from higher-cost producers until it fills all of its capacity. Ultimately the lowest-cost producer should capture 100 percent of the market if he expands capacity to meet demand.

There are several reasons why industries don’t always evolve this way. Antitrust regulations discourage single-player dominance in most industries. Often the low-cost producer has inadequate resources to build the capacity to cover the entire industry. Even if the firm has the resources, it might not want to take on the risk of putting all its eggs in one basket. To avoid problems of demand fluctuations such as those created by seasonality or business cycles, the company might restrict its capacity and raise its prices above its own costs, thereby leaving some market share for a second or third player. This forces some of the risk of demand fluctuations onto the higher-cost players and concedes the unattractive niches to competitors. This strategy satisfies the pressure on the low-cost producer for shortterm profits and allows the company to share the market with a smaller, higher-cost player for antitrust reasons.

If the low-cost producer does not capture the entire market, the second- or third-lowest-cost producers move into this opening with goods at their higher costs. This depends on the capacity of the next two or three players compared to the demand for the product beyond what is fulfilled by the lowest-cost player in the industry. In such cases, the small number of competitors makes it easy for firms to tacitly collude to keep prices up. The low-cost producer may raise his price to the cost of the second- or third- low-cost producer. This keeps everyone happy, except the customer. Of course, this collusion has to be implicit, because an explicit agreement would violate antitrust laws.

HIDDEN PRICE WARS

If, as suggested by our discussion of restraint, prices in the industry have equalized at a point above the costs of the lowest-cost producer, this allows room for more subtle price wars: disguised price wars and phantom price wars.

In disguised price wars, financing, installation and repair services, or replacement parts can be used to adjust the final price of the product up or down without changing its initial offering price. The initial price is kept high, but the company offers incentives that reduce the actual price. This might be an airline that provides frequent-flier points, an automaker offering zero-percent financing, or a manufacturer who provides lower-cost replacement parts or a better delivery schedule to cut the buyer’s inventory costs.

In phantom price wars, the initial price is kept low, but it is made up for by higher prices for using the product. For example, a car may have a low sticker price but high costs for replacement parts and maintenance, or Polaroid may offer lower instant camera prices but higher film costs than Kodak, or vice versa.

These strategies often create switching costs for the customer. Customers with frequent-flier points, trade-in allowances, or a design based on nonstandard replacement parts will be less price sensitive on their second purchases. The features that link the customers to the original supplier raise the perceived value of the product. This begins to shift the focus of competition from price to quality and service.

THE PERILS OF PRICE WARS

There is a strong incentive to move away from price wars. As we saw in Tylenol’s battle with Datril, price wars are brutal. They are the economic equivalent of the game of holding one’s breath to see who turns blue first. The individual with the greatest lung capacity wins, but both end up weakened and exhausted. (See Chapter 4 on deep pockets for more about this aspect of dynamic strategic interaction.)

Price wars produce profits only if costs are kept well below the price during the war. The war can generate big losses because, once the weak firms are driven out of the market by a price war, the survivors often can’t recapture losses created by the war by raising prices after the war is over. If customers have no brand loyalty and no switching costs (sunk capital or personal investments related to the product that are lost if ‘the customer changes products), any subsequent increase in price will lead to defections.

In addition, it is often hard to contain the losses from a price war once one has begun. Seizing and holding market share is crucial for gaining economies of scale and to spread out fixed costs over a large volume. So all firms will try to keep their prices at the lowest possible levels to gain economies of scale to further lower their costs. However, this squeezes profit margins in the short run. The squeeze isn’t too bad when the demand is greater than industry capacity, but it can be severe, leading to huge losses, when the demand drops below industry capacity.

This puts the company involved in price-competitive markets at the mercy of fluctuations in demand. When demand declines, the price war will worsen and a shakeout often occurs. This is not a favorable situation for the long-term success of most firms. It drives many firms to seek a higher level of competition—on both price and quality—thereby escalating the conflict one more notch on the escalation ladder.

3. The Second Dynamic Strategic Interaction:

Quality and Price Positioning

GENERIC STRATEGIES EVOLVE

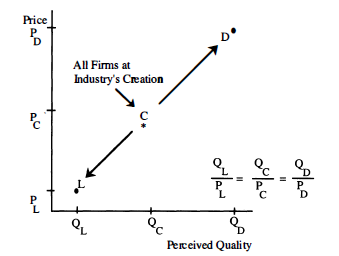

To escape the price war, companies differentiate themselves by quality as well as by price. Some firms move from point C in Figure 1-2 to what Porter calls the low-cost producer position (L), offering a lower price and a lower-quality product. Others become what Porter calls differentiators (position D), offering a product with a premium price and higher perceived quality.

FIGURE 1-2

GENERIC STRATEGIES

As shown in Figure 1-2, the value (quality-price ratio) remains constant across the high and low ends of the line in the graph. The low-cost producer and differentiator firms serve fundamentally different groups of customers, but they offer similar value in the sense that customers get the level of quality they are willing to pay for.

For commodity products, the movement to D and L may seem impossible. It would appear that these industries should stay locked in perpetual price wars. But in most commodity industries, such as steel and paper, resourceful organizations have found ways to differentiate their products based on quality or service. While traditional U.S. and Japanese steelmakers wrestled to cut the costs of their products, the U.S. minimills quietly changed the rules of the game. The minis can produce specialty steels from scrap metal much more quickly and cheaply than the large steel mills. Advances in technology that improved the output of these small mills have made them a more serious threat to the large U.S. mills than the Japanese. From 1980 to 1990, their share of the domestic market has risen from 28 percent to 37 percent.6

Through downstream vertical integration Kimberly-Clark transformed itself from a lumber and paper company into a consumer-products company. It differentiated specific brands of bathroom tissues, sanitary napkins, and disposable diapers. The company moved out of the price wars in the commodity paper and pulp industry into more stable markets where it could compete on both quality and price.

The desirability of each position (L vs. D) depends on the number of firms that move into each position, the size of the customer base desiring products at that price-quality level, the ability of others to enter the market segment later, and changes in the economy or demographics that might shift customer preferences from high- to low-priced goods or vice versa.

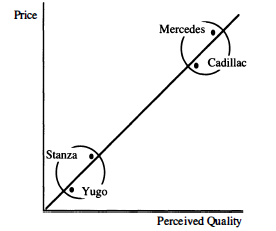

WITHIN-SEGMENT POSITIONING

Once these positions are staked out clearly, a new form of competition results. If there is more than one firm at each position, there can be smaller price and/or quality skirmishes at each position. The value (ratio of quality to price) offered by groups of firms within each position could vary, so some customers may start moving toward the firm that offers the higher value at that position. For example, within the luxury car segment of the auto market, the differentiator position, there are many competing manufacturers offering various combinations of price and quality. As indicated in Figure 1-3, within the differentiator position of the larger industry, some customers might perceive Mercedes as the differentiator compared to Cadillac’s position. Within the low-cost producers, some customers might perceive Nissan’s Stanza as a differentiator compared with Yugo.

FIGURE 1-3

WITHIN-SEGMENT COMPETITION

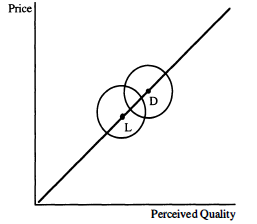

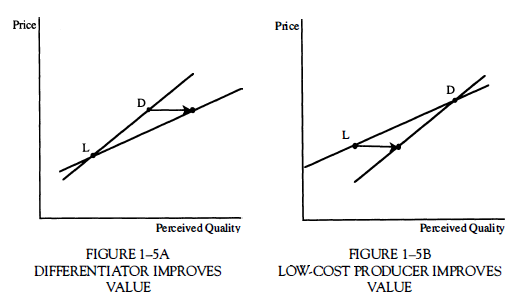

BETWEEN-SEGMENT POSITIONING

Thus, the battle shifts to price and quality differentiation within each segment. However, this type of competition can escalate to even higher levels—competition between segments. This occurs in two ways. Either the distance between L and D can be reduced so that the two segments overlap (as shown in Figure 1-4) or the value offered by L or D can be improved (as shown in Figures 1-5a and 1-5b). The first method allows L to siphon off the low end of D’s market or D to siphon off the high end of L’s market. The second method forces (1) low-end consumers to decide whether they want to pay the lowest total price or get the highest value (quality per dollar) for their money (Figure 1-5a) and (2) high-end consumers to decide whether they want to buy the highest-overall-quality product or get the highest value (quality per dollar) for their money (Figure 1-5b). Thus, the next rung in the escalation ladder is reached by gradual extension of the methods used in the war on price and quality within each segment.

FIGURE 1-4

SEGMENT OVERLAP

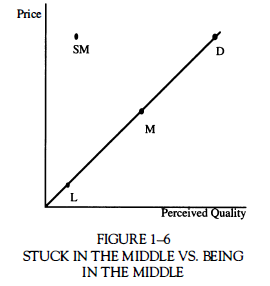

4. The Third Dynamic Strategic Interaction: The Middle Path

BEING IN THE MIDDLE

The simplest way to outmaneuver firms at Dor L is to try to move into the middle position (position Min Figure 1-6). This is not such a bad spot to be in, as long as the company can offer the same value as D and L. It can then draw away some of their customers, both low-end customers seeking slightly higher quality and high-end customers seeking slightly lower prices. As long as the overall value remains the same, customers are often willing to make some movement down or up along the constant value line shown in Figure 1-6. This suggests that being in the middle can be perilous if it overlaps too much with the firms staking out the L and D positions. If provoked, firms in positions L and D may launch a two-front attack on firms in position M and squeeze it from both sides.

BEING STUCK IN THE MIDDLE

In contrast to being in the middle, a firm can be in even more trouble if it is positioned at SM in Figure 1–6. If the company is at point SM, at a lower value ratio, it will have a harder time competing, since it will be what Porter calls “stuck in the middle.” The company may be able to carve out a niche for itself as a high-cost, low-quality player if it serves a niche that no one else is currently selling to or if it can offer something unique—like service or convenience—that compensates for the lower perceived quality of the product itself. But it is unlikely that it will survive at this point over the long haul unless it finds a way to make up for the high price of its low-quality goods with some unique service or attribute for a specialized niche of customers. Most customers will ask themselves why they should buy from SM when they can get higher quality at the same price from D or get the same quality for a lower price from L. In most cases only a few customers want the unique service or convenience of SM enough to trade off cost or quality. If SM can move to point M, with the same value ratio as the two extreme players, it • has a better chance of staking out a viable segment of the market.

As noted above, the M position could provoke a response from D (who might reduce price) or from L (who might raise quality) to squeeze M out of the market. Thus, the M position can be unstable unless D and L are so far away in price and quality that they are in segments of the market that are not threatened by M. (For example, if L is a VW Beetle and D is a Rolls Royce, there is plenty of room for a Buick to stake out position M.) Even if M is not a defensible position, it might be a good offensive move. It disrupts the original positions of D and L and costs them money, perhaps even forcing D and L to move out of their original positions to make room for a determined, aggressive firm staking out position M. This strategy is also expensive for M and probably requires either deep pockets or a weak adversary to make it work.

If the distance between D and L is large, then there will be a hole in the middle where a new entrant can make inroads or a current player can move. If the distance between D and L is small, on the other hand, en, trants can attack by outflanking at the high end or low end of the market. So whichever position competitors D and L take can be outmaneuvered, as we will see in the next two dynamic strategic interactions.

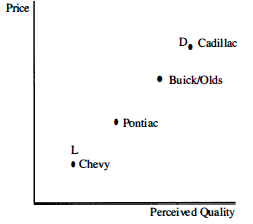

5. The Fourth Dynamic Strategic Interaction: Cover All Niches

A GIANT MAKER: THE FULL-LINE PRODUCER STRATEGY

Because of this threat of entry at the middle of the market, which would require costly defensive moves, companies such as D and L often try to protect themselves against this type of attack. This escalates the level of competition from battling over the positions of individual products to competing as fulhline producers. Food companies, for example, have at, tempted to fill up the breakfast cereals market with numerous brands to fill all the niches, making it hard for anyone to enter the market with suffi, dent economies of scale by squeezing into the small remaining niches be, tween existing brands. Again, the last dynamic strategic interaction (mov, ing into the middle) causes an escalation by forcing firms to gain access to more of the market to make it harder for new entrants to find a niche in the middle.

General Motors was one of the originators of the fulhline strategy. Customers can start with a Chevy and, as their income increases, move up through Pontiacs, Buicks, and Oldsmobiles to Cadillacs (see Figure 1-7). IBM also took this approach with its System/360 series in 1964, the first family of compatible computers that spanned the market from the high end to the low end. Six compatible processors were in the family, the big, gest of which was fifty times faster than the smallest. And the company continued to add more models to the line over the years. The 360 series set the standard for the industry for decades after its launch. Both GM and IBM serviced customers over their lifetime by encouraging trade-up to higher-and-higher-priced products. This full-line producer strategy has been so successful that it has built some of the largest firms (like GM and IBM) in the world.

FIGURE 1-7

GM’S FULL LINE

DIFFICULTIES WITH FULL-LINE PRODUCER STRATEGIES

While there are obvious advantages to this approach, this strategy, like all others, is open to being outmaneuvered. In most industries firms cannot span the entire price-quality continuum, and customers don’t trade up. There are, instead, distinct market segments with completely different critical success factors. In breakfast cereals, for example, the all-natural healthy breakfast segment opened up, allowing entry to segments that very few of the existing brands covered. In addition, in some industries, applying the same company name to a wide range of products can cause a confused image among consumers, as some lines of hotels are finding. For example, the use of a hotel’s name on low-end inns has tainted the high end of the hotel chain, while the low-end inns aren’t perceived as low-priced because of the high-end hotel name. Often this problem can be solved by applying different brand names to different segments of the market, as Honda did for its highest-end product, Acura. However, it is often difficult to be both a low-cost producer and a differentiator at the same time. It may be impossible, for example, to be both a low-cost producer of mass- merchandised chain saws for casual users while still providing the high-overhead services demanded by the professional end of the market. The casual market requires simple saws with a short useful life (approximately one hundred to two hundred hours of use over a lifetime). The professional market requires complex, powerful saws to cut down a wide variety of trees and useful lives of several thousand hours. Manufacturing methods and distribution outlets are so entirely different for the two markets that they would have to be done by entirely different subunits of the company, each recognizing the completely different critical success factors relevant to the segments.

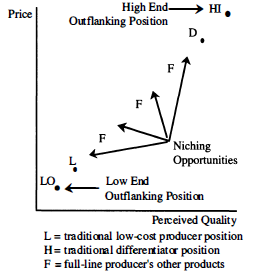

5. The Fifth Dynamic Strategic Interaction: Outflanking and Niching

FILLING IN THE HOLES

Even when it is possible to pursue a full-line strategy, covering the market does not always prevent entry by competitors. While the full-line producer is forced to look at the big picture, smaller players can enter by focusing on small segments of the market. If there is sufficient room for growth within a single market segment, some companies may decide to stake out that point on the price-quality continuum and concede other positions to fullline competitors. Others will go to the extremes of the market, targeting the high end or low end not covered by the full-line producer.

Apple moved into the low end of the computer market with its personal computer, ultimately threatening IBM’s position as a full-line mainframe producer. Big Blue also faced competition from smaller companies that carved out niches in mainframe markets. Finally, it was taken on in price on its own personal computer by a host oflow-cost clone makers. IBM saw its hold on the world computer market drop from around 30 percent in 1985 to 21 percent in 1990, according to Management Today.7 Similarly, Japanese automakers moved in on the low end of the U.S. auto market, starting below the low end of GM’s line. They then moved up. More recently, Japanese automakers have seized the high end of the U.S. auto market (staking out ground just above GM’s Cadillac but below the cost of foreign imports).

CREEPING UP AND DOWN

While niching and outflanking competitors are not a tremendous threat to the full-line producers at the outset, in the long run they can spread across the market like a forest fire, as was the case in the U.S. auto market. By establishing themselves in a small segment, they can move out to take over progressively larger portions of the market.

FIGURE 1–8

TYPICAL ENTRY BY OUTRANKING AND/OR NICHING

Competitors can either enter high and move down or enter low and move up (see Figure 1-8). They can also grab up any unoccupied space in the middle of the market. Large companies lose interest in these niche segments when they become too small to be profitable. Even then, smaller companies can still move in and make a profit in these niches. Eventually they can also become full-line producers as they fill in all the holes.

Some companies cannot or do not move out of their niche. For example, when Mercedes entered the U.S. auto market, it remained at the high end. BMW, Volvo, and Saab, on the other hand, entered at the high end and crept down, some more so than others.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Volkswagen created and dominated the subcompact market with its Beetle but had trouble creeping up. The Rabbit took a nosedive, and VW’s market share fell from 7.2 percent in 1970 to 2.6 percent in 1983.8 Amidst rising costs and concerns about quality, VW was initially swept away by a wave of competitors who had entered the low-end niche with newer and less-expensive, high-mileage cars. These manufacturers, many of them Japanese, then proceeded to move up to higher ends of the market. Thus, VW’s upward move was hindered more by implementation errors than by a weakness in the essential strategy.

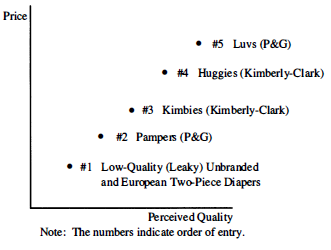

Another example of high-end outflanking can be seen in the disposable diaper wars, as shown in Figure 1-9. (Perceived quality is noted in this figure for illustrative purposes rather than as a reflection of a formal evalu, ation of consumer perceptions.) Procter & Gamble defined the market in 1961 with the introduction of Pampers, defeating several European,style two,piece diapers and unbranded low quality (leaky) diapers being tested in the U.S. market. Seven years later, Kimberly,Clark entered the market with Kimbies and quickly snatched 20 percent of the market share with its innovative designs, according to The Wall Street Joumal.9 But Kimberly, Clark rested on its laurels and shifted its focus away from innovation, allowing P&G’s quality to catch up with Kimbies. Its sales plummeted, and the company debated whether to stay in the disposable market. 10 Kimberly,Clark staged a comeback in 1978, moving up in both price and quality with the introduction of Huggies. Two years later, Procter & Gamble followed suit with the introduction of Luvs. Luvs and Huggies fought for the same piece of the market. They continue to jockey for posi, tion in the market, constantly raising the upper end of the market by add, ing new features. In 1989, when Luvs introduced separate diapers for boys and girls, it surged past Huggies Supertrim to become the number one brand in food store sales. When Huggies got Muppet Babies, Luvs found Sesame Street baby characters.11 The latest innovation has been diapers designed for specific stages in the child’s development. There has also been recent competition on reducing environmental impact, resulting in competition to reduce waste.

FIGURE 1-9

CREEPING UP THE LINE IN DIAPERS

At the same time, these diaper makers have increased the quality of the low end of the market by selling their excess capacity to generic brands distributed through supermarket chains. In addition, product features are often imitated and leakage is no longer a problem for the unbranded, low, end diapers. This has allowed these low-cost producers to move toward higher quality (i.e., the lower right-hand comer of Figure 1-9), making the whole market more price competitive. In response P&G and Kimberly-Clark are using heavy marketing of their diapers and the ceaseless introduction of new features. This has slowed, but not eliminated, this movement toward a commodity market.

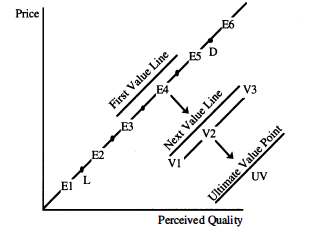

6. The Sixth Dynamic Strategic Interaction: The Move toward Ultimate Value

Some of the new products designed to niche or outflank existing products carve out niches that overlap with those of existing competitors. Some firms creep up or down to consume more of the market from the full-line producer. This forces the existing competitors to respond by offering better values to the customers by lowering price, raising quality, or both. In addition, the aggressive firms find that it can be difficult to simply move up or down into the markets of the full-line producers unless they can offer either better quality or lower price than the full-line producers. This leads to the next dynamic strategic interaction: the move toward ultimate value.

Ultimate value is what economists refer to as “perfect competition,” the point at which all players are driven down to similar levels of price and quality and no one has any competitive advantage. Competitors in some industries never reach this point, even though they are continually moving in the direction of lower costs and higher quality. Other industries arrive there briefly and then move off by restarting the cycle of competition or jumping to another one of the four arenas. Others freeze there for years if the firms hit the theoretical envelope for quality and cost improvement and if the firms are not very clever about how to move that envelope.

While the average competitor fights for niches along a common ratio of price and value (“You get what you pay for”), innovative firms can enter the market by providing better value to the customer (“You get more than what you pay for”). These companies offer lower cost and higher quality than their competitors (see Figure 1-10). This shift in value is like lowering the stick while dancing the limbo. All the competitors have to do the same dance with tighter constraints on both costs and quality.

For example, when Honda and other Japanese automakers brought a quality revolution to the auto industry, they redefined the levels of cost and quality in the field. American car companies were forced to redirect their efforts to generating higher quality and slashing prices, either directly or through rebates. It brought them to a new and more intense level of competition.

HGURE 1-10

THE MOVE TOWARD OFFERING

ULTIMATE VALUE

The disposable diaper market is also moving in the same direction. As the market gets more price competitive, it is also moving toward higher levels of quality (less leakage, greater absorbency, greater thinness, etc.). The products are offering higher and higher value to customers as the competition between firms gets heated. As incremental product improvements are becoming more marginal, quality differences are disappearing between brands (because everyone offers high quality). But the competitors continue to make these incremental improvements as a means of gaining a temporary advantage.

This move toward higher value (lower-price, high-quality products) continues to approach the point UV on Figure 1-10, ultimate value. This UV position makes all other positions unviable. UV offers better quality for the same low price to customers seeking low prices, and it offers a lower price for the same high quality for those seeking quality. To survive, other firms are forced to move toward the UV point by lowering their prices and raising quality. This movement has been speeded up by practices such as the benchmarking of best-in-class competitors. Over time, the market becomes commodity-like when all firms evolve to the same low price and high quality position.

Of course, as we have noted, not all industries can be reduced to a single point of ultimate value. It seems very unlikely, no matter what technological advances are made in car production, that the auto industry would become a commodity-like industry. But a growing emphasis on quality in that industry has caused the line of competition to shift toward a position of ultimate value within each segment of the market. The segments may still fall along a line with a high end and a low end, but all producers along the way will offer a much better ratio of price and quality. Moreover, the line will continue to move toward the ultimate value corner of the graph (Figure 1-10), and many manufacturers will offer similar lines. At each step of the process, competitors seek a temporary advantage with new price and quality initiatives. Thus, the process of competition forces firms to offer a line of high-quality, low-priced goods that eventually make high quality and lower prices a necessity for survival. Competitive advantage is not created by price-quality positioning when this occurs.

Sometimes companies stop at what appears to be a point of ultimate value when they hit a technological barrier that prevents them from lowering cost or increasing quality. This allows other firms to catch up and creates an environment similar to perfect competition. But this situation is sometimes eroded after a period of time either by a technological breakthrough or through the application of new approaches to the product or service that restarts the movement toward UV. Whether the process of movement stops or continues, at some point in time everyone loses the ability to win by competing along the price and quality dimensions because differences between competitors become smaller and smaller. They also become harder and harder to achieve.

REVOLUTIONARY JUMPS TO THE ULTIMATE-VALUE POSITION

Sometimes the movement toward ultimate value occurs in a brief flash because of a single technological innovation, such as Pilkington’s development of a new process for producing plate glass.

Before Pilkington’s introduction of this technology, which floated a ribbon of glass on a bath of molten tin, glass purchasers had a choice between low- cost, low-quality sheet glass and high-cost, high-quality plate glass. The sheet glass was too crude to be used for such applications as shop windows, cars, and mirrors. Plate glass was made by grinding down sheet glass to make it smoother, but this was a very expensive and time-consuming process.

The development of Pilkington’s new float process in the late 1950s transformed the industry. And Pilkington moved from being a participant in the sleepy world glass industry to being the largest glass manufacturer in the world, selling its products in more than thirty-three countries around the globe. It also exported its technology. Because of the high cost of developing the new process, Pilkington licensed the process to its competitors, and it soon became the standard for the industry, making the flat glass industry more of a one-segment commodity market offering only low-cost, high- quality flat glass.

This controversial strategy of giving away its advantage to its competitors generated substantial income for Pilkington, helping to assure its continued technological leadership in the industry for decades. Thus, one method for moving toward the ultimate value position is to look for revolutionary process innovations that simultaneously raise quality and lower price. As we will examine in Chapter 2, even technological innovations that increase quality and lower cost provide only a temporary advantage. Even if the innovator does not license the new process as Pilkington did, other competitors will eventually catch up or surpass this level of quality and cost, restarting the competition at a higher level.

TWO-STAGE MARCHES TOWARD ULTIMATE VALUE

Not all moves toward ultimate value occur with the rapidity of Pilking- ton’s transformation of the flat glass market. It is hard to transform both price and quality at the same time ( unless the company can use a process innovation such as Pilkington’s). Improvements in quality very often strain costs, and reductions in price very often strain quality. Usually companies move from M to D or L, concentrating on cost or quality first, and then proceed toward ultimate value.

Whereas Pilkington’s process innovation transformed both quality and price simultaneously in the industry, slower strategies call for a two-step process in changing these two factors. These two-step processes can work in two directions. The first approach is for the company to enter with a low quality and low price and then raise its quality, raising value while keeping price constant. The second approach is to enter with a high quality and high price and then lower costs and prices, raising value while holding quality constant.

When Toyota and Nissan entered the U.S. auto market, they were first low-cost producers. As they continued to lower their costs, they could then reinvest their profits to raise quality without raising price. This way they moved to a higher value point. Similarly, Gallo entered the wine industry with low-cost wines, then made incremental improvements to move to more upscale wines at popular prices, offering better and better value.

Another approach is to enter as a differentiator at the high end of the spectrum. Keeping quality high, the firm then reinvests profits to lower its costs and price. This also moves the industry toward a position of higher value.

DRIFTING TOWARD ULTIMATE VALUE

Some industries take neither a dramatic nor a steady, strategic route to ultimate value. They simply move toward it by a gradual drift. This even happens in industries that have reached an equilibrium, with low-cost producers staking out the low end, differentiators staking out the high end, and fringe players focusing on small segments in between.

Even in this apparent steady state, dynamic strategic interactions continue to work beneath the surface to move the segment toward higher value. The interactions within each segment create pressures for higher value. The low-cost producers try to outposition other low-cost producers. The winner is the one that can offer the highest quality for the lowest price. At the high end the differentiators continue to jockey for position, lowering price or raising quality, moving toward higher value. The pressures from these two small sets of interactions tend to move the entire industry toward the ultimate value point.

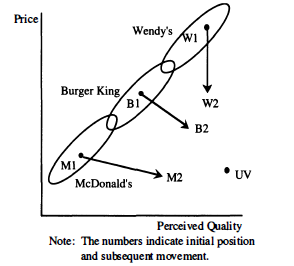

We can see this drift toward ultimate value in the competition among fast-food hamburger restaurants, as shown in Figure 1-11. As the industry emerged, McDonald’s was at the lower end of the cost-quality spectrum, offering low-priced, moderate-quality food. Burger King raised the quality a notch by offering custom-made burgers (“have it your way”) that were flame-broiled. Wendy’s, and others, later entered with larger portions, salad bars, and higher quality at higher prices. (Of course, there are high- and low-end nichers in the fast-food hamburger industry, but we consider three to simplify this discussion.)

If McDonald’s, Burger King, and Wendy’s had originally positioned themselves at points far enough apart (points Ml, Bl and Wl on Figure 1-11) so that they had their own separate niches, there might have been no “burger wars.” But each firm’s niche overlapped, so they competed for customers “on the margin,” i.e., those who might switch between the competitors. So McDonald’s, in response to the “have it your way” campaign, took on Burger King by offering more customization and variety without long waits, moving to M2. This variety was heightened with the entry of Wendy’s and others who offered salads, chili, baked potatoes, and other goodies. By improving customization and product variety, McDonald’s increased its overall quality. Burger King, competing directly with McDonald’s on price, dropped price and increased variety to offer higher quality, moving to B2. Wendy’s, after establishing its quality leadership, moved to offering ninety-nine-cent value items and other strategies for reducing price, moving to W2. This process of dynamic strategic interaction has pushed the three restaurants toward the point of ultimate value. Although there are value distinctions among the three competitors, they act more and more like direct competitors in one niche.

FIGURE 1-11

THE DRIFT TOWARD ULTIMATE VALUE IN FAST-FOOD HAMBURGER INDUSTRY

In industries such as fast food, the point of ultimate value is not really a point. It is a direction that all firms constantly strive for because, in some circumstances, human ingenuity can constantly create new ways to move to higher levels of value. This is the concept behind Kaizen, the Japanese ideal of continuous quality improvement. Perfect competition still results in this situation, especially when all the competition is moving uniformly toward that point at the same rate. As long as no one has a substantial lead, high quality and low cost positioning provides no advantage. They become, however, necessities for survival.

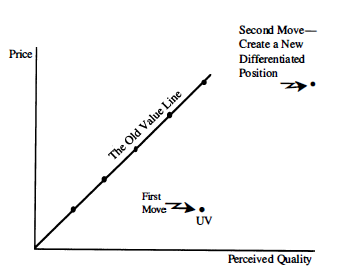

7. The Seventh Dynamic Strategic Interaction: Escaping from the Ultimate Value Marketplace by Restarting the Cycle

As industries move toward ultimate value, profits are squeezed and compe-tition intensifies. Competitors who are far from the UV point are doomed.

They can provide neither higher quality nor lower prices. As soon as customers discover this, these firms are history. The players that remain are battling for a single position, a small island of success. Price-quality positioning has led the industry back to a perfectly competitive, commodity-like market, where quality is a necessity, not a source of advantage.

Competitors begin to look for ways to escape from their profitless efforts. There are a variety of options for breaking free, but most of these options throw competitors into a new, more competitive cycle. Among the options are the following:

- Shifting the graph: A company can shift the entire graph so that the UV position is either the low-cost producer or differentiator. By moving the benchmark for good quality or reasonable price, they make the UV point the middle or low or high end of the price-quality continuum. Then the cycle of cost-quality maneuvering begins again because a new value line is created. See Figure 1-12 for an example of creating a new differentiator position.

- Redefining perceived quality: By changing the definition of perceived quality, a company can redefine the graph and create a new point of ultimate value. For example, quality in the auto industry shifted during the gas crisis to fuel economy but has now been redefined as safety and comfort. Again, this restarts the cycle of cost-quality maneuvering, using the new dimensions of quality.

FIGURE 1-12

SHIFTING THE GRAPH TO OUTMANEUVER FIRMS OFFERING THE VALUE PRODUCT

- Shift from product to service: One way to redefine product quality is to make service a key component of overall quality. The product-service bundle increases the value to the customer. In the early 1980s IBM made this shift in focus from making machines to providing software and high levels of service to customers. Intel used the better service offered by designing customized microchips to add value to its products. Again, this restarts the cycle of cost-quality maneuvering, using the new service dimensions to define quality.

- Micromarketing and masscustomization: With advances in computing technology such as CAD/CAM and flexible manufacturing, companies can quickly tailor their product to many different customer needs. This provides virtually unlimited product differentiation. Again, product variety enhances the quality of the firm’s overall offerings. This also restarts the cost-quality cycle from scratch.

The problem with all these approaches is that they are imitable and restart the cycle of the first six dynamic strategic interactions. And once all competitors have implemented them, they no longer provide any advantage. Moreover, the competitors are forced to escalate from lower levels to higher levels of competitiveness to keep from being left behind.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.