Although initial structure, structural potential, and particular firms’ investment decisions will be industry-specific, we can general-ize about what are the important evolutionary processes. There are some predictable (and interacting) dynamic processes that occur in every industry in one form or another, though their speed and direc-tion will differ from industry to industry:

- long-run changes in growth;

- changes in buyer segments served;

- buyers’ learning;

- reduction of uncertainty;

- diffusion of proprietary knowledge;

- accumulation of experience;

- expansion (or contraction) in scale;

- changes in input and currency costs;

- product innovation;

- marketing innovation;

- process innovation;

- structural change in adjacent industries;

- government policy change;

- entries and exits.

Each evolutionary process will be described, with attention to its determinants, its relationship to other processes, and its strategic implications.

1. LONG-RUN CHANGES IN GROWTH

Perhaps the most ubiquitous force leading to structural change is a change in the long-run industry growth rate. Industry growth is a key variable in determining the intensity of rivalry in the industry, and it sets the pace of expansion required to maintain share, thereby influencing the supply and demand balance and the inducement the industry offers to new entrants.

There are five important external reasons why long-run industry growth changes:

DEMOGRAPHICS

In consumer goods, demographic changes are one key determi-nant of the size of the buyer pool for a product and thereby the rate of growth in demand. The potential customer group for a product may be as broad as all households, but it usually consists of buyers characterized by particular age groups, income levels, educational levels, or geographic locations. As the total growth rate of the popu-lation, its distribution by age group and income level, and demo-graphic factors change, these translate directly into alterations in de-mand. A particularly vivid current example of this situation is the adverse effect of the reduced U.S. birthrate on demand for baby products of all types, whereas products catering to the 25-to-35-year- old age group are currently enjoying the effects of the post–World War II baby boom. Demographics also represent a potential prob-lem for the recording and candy industries, which have traditionally sold most heavily to the pre-20-year-old age group, which is current–ly shrinking.

Part of the effect of demographic changes is caused by income elasticity, which refers to the change in a buyer’s demand for a prod-uct as his/her income rises. For some products (mink golf club covers), demand tends to rise disproportionately with buyers’ in-come. For other products, demand rises less than proportionally as incomes rise, or even falls. It is important from a strategic point of view to identify where an industry’s product lies in this spectrum, because it is critical to forecasting long-run growth as general in-come levels of buyers change both in a firm‘s home country and in potential international markets. Sometimes industries can shift their products up or down the scale of income elasticity through product innovation, however, so the effects of income elasticity are not nec-essarily a foregone conclusion.

For industrial products, the effect of demographic changes on demand is based on the life cycle of customer industries. Demo-graphics affect consumers’ demand for end products, which filters back to affect the industries supplying inputs toward those end prod-ucts.

Firms can attempt to cope with adverse demographics by widen-ing the buyer group for their product through product innovations, new marketing approaches, additional service offerings, and so on. These approaches’ can in turn affect industry structure by raising economies of scale, exposing the industry to fundamentally different buyer groups with different bargaining power, and so forth.

TRENDS IN NEEDS

Demand for an industry’s product is affected by changes in the lifestyle, tastes, philosophies, and social conditions of the buyer population which any society tends to experience over time. For ex-ample, in the late 1960s and early 1970s there were such shifts in the United States as a return to “nature,” increased leisure time, more casual dress, and nostalgia. These trends boosted demand for back-packs, blue jeans, and other products. The recent “back to basics” movement in education is creating new demand for standardized reading and writing tests, to give another example. There have also been social trends such as an increase in the crime rate, the changing role of women, and increased health consciousness that have in-creased demand for some products (bicycles, day care) and reduced demand for others.

Trends in needs like these not only directly affect demand but also affect the demand for industrial products indirectly through in-tervening industries. Trends in needs affect the demand in particular industry segments as well as total industry demand. Needs may be newly created or just made more intense by social trends. For exam-ple, property theft has increased quite dramatically in the last twenty years, greatly increasing the demand for security guards, locks, safes, and alarm systems. The rising expected losses due to theft have justified greater spending to prevent it.

Finally, changes in government regulation can increase or de-crease needs for products. For example, demand for pinball and slot machines is growing as a result of impending and already passed leg-islation that legalizes gambling.4

CHANGE IN THE RELATIVE POSITION OF SUBSTITUTES

Demand for a product is affected by the cost and quality, broadly defined, of substitute products. If the cost of a substitute falls in relative terms, or if its ability improves to satisfy the buyer’s needs, industry growth will be adversely affected (and vice versa). Examples are the inroads that television and radio have made on the demand for live concerts by symphony orchestras and other perform-ing groups; the growth in demand for magazine advertising space as television advertising rates climb sharply and prime advertising tele-vision time becomes increasingly scarce; and the depressing effect of rising prices on the demand of such products as chocolate candy and soft drinks relative to their substitutes.

In predicting long-run change in growth, a firm must identify all the substitute products that can meet the needs its product satis-fies. Then technological and other trends that will affect the cost or quality of each of these substitutes should be charted. Comparing these with the analogous trends for the industry will yield predictions about future industry growth rates and identify critical ways in which substitutes are gaining, thereby providing leads for strategic action.5

CHANGES IN THE POSITION OF COMPLEMENTARY PRODUCTS

The effective cost and quality of many products to the buyer de-pends on the cost, quality, and availability of complementary prod-ucts, or products used jointly with them. For example, in many areas of the United States mobile homes are primarily sited in mobile home parks. In the last decade there has been a chronic shortage of these parks, which has limited demand for mobile homes. Similarly, demand for stereophonic records was strongly affected by the avail-ability of stereophonic audio equipment, which in turn was affected by the cost and reliability of this equipment.

Just as it is important to identify substitutes for an industry’s product it is important to identify complements comprehensively. Complementary products should be viewed broadly. For example, credit at prevailing interest rates is a complementary product to pur-chases of durable goods. Specialized personnel are a complemeritary product to many technically oriented goods (e.g., computer pro-grammers to computers and mining engineers to coal mining). Charting trends in cost, availability, and quality of complementary products will yield predictions about long-run growth for an indus-try’s product.

PENETRATION OF THE CUSTOMER GROUP

Most very high industry growth rates are the result of increasing penetration, or sales to new customers rather than to repeat custom-ers. Eventually, however, it is a fact of life that an industry must reach essentially complete penetration. Its growth rate is then deter-mined by replacement demand. Renewed periods of adding new cus-tomers can sometimes be stimulated by product or marketing changes, which broaden the scope of the customer base or stimulate rapid replacement. However, all very high growth rates eventually come to an end.

Once penetration is reached the industry is selling primarily to repeat buyers. There may well be major differences betweeen selling to repeat and first-time buyers that have important consequences for industry structure. The key to achieving industry growth when sell-ing to repeat buyers is either stimulating rapid replacement of the product or increasing per capita consumption. Since replacement is determined by physical, technological, or design obsolescence as per-ceived by the buyer, strategies to maintain growth after penetration will hinge on affecting these factors. For example, replacement de-mand for clothing is stimulated by annual and even seasonal style changes. And the classic story of General Motors’ ascendency over Ford is an example of how model changes stimulated demand after market saturation for the basic (one color: black) automobile oc-curred.

Whereas penetration most often means that industry demand will level off, for durable goods, achieving penetration can lead to an abrupt drop in industry demand. After most potential customers have purchased the product, its durability implies that few will buy replacements for a number of years. If industry penetration has been rapid, this situation may translate into several very lean years for in-dustry demand. For example, industry sales of snowmobiles, which underwent very rapid penetration, fell from 425,000 units per year in the peak year (1970-1971) to 125,000 to 200,000 units per year in 1976-1977.6 Recreational vehicles underwent a similar though not quite so dramatic decline. The relation between the growth rate after penetration and growth before penetration will be a function of how fast penetration has been reached and the average time before re-placement, and this figure can be calculated.

The decline in industry sales for durables means that manufac-turing and distributing capacity will inherently overshoot demand. As a result, a serious decline in profit margins usually occurs, and some producers may exit. Another characteristic of the demand for durable goods is that growth fueled by penetration can overshadow cyclically despite the fact that the product is inherently sensitive to the business cycle. An industry approaching penetration will thus have its first deep cycle, exacerbating the problem of overshooting.

PRODUCT CHANGE

The five external causes of industry growth have presupposed no change in the products offered by the industry. Product innova-tion by the industry, however, can allow it to serve new needs, can improve the industry’s position vis-à-vis substitutes, and can elimi-nate or reduce the necessity of scarce or costly complementary prod-ucts. Thus product innovation can improve an industry’s circum-stances relative to the five external causes of growth, and thereby increase the industry’s growth rate. Product innovations have played a major part in fueling the rapid growth of motorcycles, bicycles, and chain saws, for example.

2. CHANGES IN BUYER SEGMENTS SERVED

The second important evolutionary process is change in the buyer segments served by the industry. For example, early electronic calculators were sold to scientists and engineers, only later to stu-dents and bill payers. Light aircraft were initially sold to the military and later to private and commercial users. Related to this is the pos-sibility that additional segmentation of existing buyer segments can take place by creating different products (broadly defined) and mar-keting techniques for them. A final possibility is that certain buyer segments are no longer served <

The significance of new buyer segments for industry evolution is that the requirements for serving these new buyers (or eliminating requirements for serving obsolete segments) can have a fundamental impact on industry structure. For example, although early buyers of the product may not have required credit and field servicing, later buyers might. If the provision of credit and in-house service creates potential economies of scale and raises capital requirements, then entry barriers will rise significantly.

A good example is provided by changes occurring in the optical character reader business in the late 1970s. This industry and its leader, Recognition Equipment, have been producing large, expen-sive optical scanning machines to sort checks, credit cards, and mail. Each machine has been custom-made, requiring special engineering and produced on a job-shop basis. In recent years, however, small wands for use with retail point–of-sale terminals have been devel-oped. In addition to opening up a vast potential market, the wands are amenable to high-volume, standardized manufacturing and will be purchased in large quantities by individual buyers. This develop-ment promises to change economies of scale, capital requirements, marketing methods, and many other aspects of industry structure.

Analysis of industry evolution, then, should include an identifi-cation of all potential new buyer segments and their characteristics.

3. LEARNING BY BUYERS

Through repeat purchasing, buyers accumulate knowledge about a product, its use, and the characteristics of competing brands. Products have a tendency to become more like commodities over time as buyers become more sophisticated and purchasing tends to be based on better information. Thus there is a natural force re-ducing product differentiation over time in an industry. Learning about the product may lead to increasing demands by buyers for warranty protection, service, improved performance characteristics, and so forth.

An example is the aerosol packaging industry. Aerosol packag-ing first came into use in consumer goods in the 1950s. The package, an extremely important part of marketing many consumer goods, often represents an important cost item to the marketing company. In the early years of aerosol packaging, consumer marketers were unfamiliar with how to design aerosol applications, how aerosol containers were filled, and how best to market aerosol products. A contract aerosol filling industry sprang up to assemble and fill aero-sol packages, and this industry also played a major role in assisting consumer marketing companies find new aerosol applications, solve production problems, and so on. Over time, however, consumer marketers learned a great deal about aerosols and began developing their own applications and marketing programs, in some cases actu-ally initiating integration backward. Contract fillers found it in-creasingly difficult to differentiate their services, and their role be-came increasingly one of supplying commodity aerosol containers. As a result, contract fillers’ profit margins were severely squeezed, and many left the industry.

A buyer’s learning tends to progress at different rates for differ-ent products, depending on how important the purchase is and the buyer’s technical expertise. Smart or interested (because it is an im-portant product) buyers tend to learn faster.

Offsetting buyer’s experience is change in the product or in the way it is sold or used, such as new features, new additives (hexa- chlorophine), style changes, new advertising appeals, and the like. This development nullifies some of the buyer’s accumulated knowN Analysis of industry evolution, then, should include an identifi-cation of all potential new buyer segments and their characteristics.

4. LEARNING BY BUYERS

Through repeat purchasing, buyers accumulate knowledge about a product, its use, and the characteristics of competing brands. Products have a tendency to become more like commodities over time as buyers become more sophisticated and purchasing tends to be based on better information. Thus there is a natural force re-ducing product differentiation over time in an industry. Learning about the product may lead to increasing demands by buyers for warranty protection, service, improved performance characteristics, and so forth.

An example is the aerosol packaging industry. Aerosol packag-ing first came into use in consumer goods in the 1950s. The package, an extremely important part of marketing many consumer goods, often represents an important cost item to the marketing company. In the early years of aerosol packaging, consumer marketers were unfamiliar with how to design aerosol applications, how aerosol containers were filled, and how best to market aerosol products. A contract aerosol filling industry sprang up to assemble and fill aero-sol packages, and this industry also played a major role in assisting consumer marketing companies find new aerosol applications, solve production problems, and so on. Over time, however, consumer marketers learned a great deal about aerosols and began developing their own applications and marketing programs, in some cases actu-ally initiating integration backward. Contract fillers found it in-creasingly difficult to differentiate their services, and their role be-came increasingly one of supplying commodity aerosol containers. As a result, contract fillers’ profit margins were severely squeezed, and many left the industry.

A buyer’s learning tends to progress at different rates for differ-ent products, depending on how important the purchase is and the buyer’s technical expertise. Smart or interested (because it is an im-portant product) buyers tend to learn faster.

Offsetting buyer’s experience is change in the product or in the way it is sold or used, such as new features, new additives (hexa- chlorophine), style changes, new advertising appeals, and the like. This development nullifies some of the buyer’s accumulated knowl-approach if its early bets about the appropriate strategy prove wrong.

5. DIFFUSION OF PROPRIETARY KNOWLEDGE

Product and process technologies developed by particular firms (or suppliers or other parties) tend to become less proprietary. Over time, a technology becomes more established and knowledge about it more widespread. Diffusion occurs through a variety of mechanisms. First, firms can learn from physical inspection of com-petitors’ proprietary products and from information gleaned from a variety of sources about the size, location, organization, and other characteristics of competitors’ operations. Suppliers, distributors, and customers are all conduits for such information and often have strong interest in promoting diffusion for their own purposes (e.g., creating another strong supplier). Second, proprietary information is also diffused as it becomes embodied in capital goods produced by outside suppliers. Unless firms in the industry make their own capi–tal goods or protect the information they give to suppliers, the tech–nology may become purchasable by competitors. Third, personnel turnover increases the number of people who have the proprietary information and may provide a direct conduit for the information to other firms. Spin-off firms founded by technical personnel who have left pioneering companies are common, as is the practice of hiring away personnel. Finally, specialized personnel who are expert in the technology invariably become more numerous from sources such as consulting firms, suppliers, customers, response of university techni-cal schools, and so on.

In the absence of patent protection, therefore, proprietary ad-vantages will tend to erode, as hard as it is for some firms to accept this fact. Thus any mobility barriers built on proprietary knowledge or specialized technology tend to erode over time, as do those caused by shortages of qualified, specialized personnel. These changes make it easier not only for new competitors to spring up but also for suppliers or customers to vertically integrate into the industry.

Returning to the previously discussed aerosol example, over time the new aerosol technology became better and better known. Since the production volume needed to achieve efficient scale in aerosol packaging was relatively small, many large consumer mar-keting companies could support their own captive filling operations.

As knowledge about the technology and specialized personnel be-came more common, many of these companies vertically integrated into aerosol filling or could threaten to do so. This development left the contract filler in the role of meeting emergency demand and in a very adverse bargaining situation. The response of many contract fillers was to invest in improving filling technology and to invent new aerosol applications to restore their technological advantage. This strategy proved to be increasingly difficult, and the contract fillers’ position weakened substantially over time.

The rate of diffusion of proprietary technology will depend on the particular industry. The more complex the technology, the more specialized the required technical personnel, the greater the critical mass of research personnel required, or the greater the economies of scale in the research function, the slower proprietary technology will tend to diffuse. When heavy capital requirements and economies of scale in R&D confront imitators, proprietary technology can provide a lasting mobility barrier.

One key offsetting force to diffusion of proprietary technology is patent protection, which legally inhibits diffusion. However, this protection is unreliable in preventing diffusion since patents can be sidestepped by similar inventions. The other offsetting force to dif-fusion is the continual creation of new proprietary technology through research and development. New knowledge will provide companies with additional periods of proprietary advantages. How-ever, continual innovation may not pay if the diffusion period is short and buyers’ loyalties to pioneering firms are not very strong.

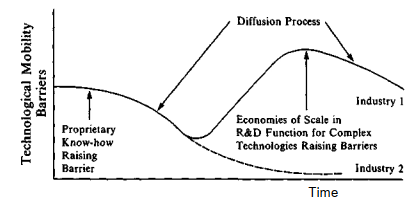

Two of many possible patterns of mobility barriers arising from proprietary technology are illustrated in Figure 8-3. Economies of scale in research were initially low in both industries since the initial, crude, breakthrough innovations that created the product could be made by small groups of research personnel. This situation is rela-tively common, having occurred in such industries as minicomput-ers, semiconductors, and others. Proprietary technology provided a modest initial mobility barrier in such an industry, but one that was soon eroded by diffusion. In one industry, the complex technology led to increasing economies of scale in the research function. In the other, there was little opportunity for continued technological inno-vation and hence little need for further research on a significant scale. In the first industry, then, mobility barriers from proprietary technology quickly rose again to a level higher than the initial one. Eventually they tailed off as opportunities for further innovation waned and diffusion took over. In the other industry, mobility bar-riers from proprietary technology quickly sunk to a low level. Thus one industry would probably have a profitable maturity phase, whereas the other would be dependent on other sources of barriers to prevent profit erosion to the competitive level. In the aerosol exam-ple, the nature of the technology did not allow the secondary in-crease in entry barriers.

FIGURE 8-3.Illustrative Pattern of Technological Barriers and Industry Evolution

From a strategic point of view, the diffusion of knowledge about technology means that to maintain position (1) existing know- how and specialized personnel must be protected, which is very diffi-cult to do in practice;7 (2) technological development must occur to maintain the lead; or (3) strategic position must be shored up in other areas. Planning for the defense of strategic position against technological diffusion takes on high priority if a firm’s existing po-sition is heavily dependent on technological barriers.

ACCUMULATION OF EXPERIENCE

In some industries, whose characteristics were identified in Chapter 1, unit costs decline with experience in manufacturing, dis-tributing, and marketing the product. The significance of the learn-ing curve for industry competition is dependent upon whether firms with more experience can establish significant and sustainable leads over others. For these leads to persist, firms that are behind must be unable to catch up by copying the methods of leaders, buying new and more efficient machinery the leaders may have pioneered, and so on. If firms that are behind can leapfrog, the leaders may be at a disadvantage from bearing the expense of research, experimenta-tion, and introduction of new methods and equipment in the first place. The tendency for proprietary technology to diffuse works against the learning curve to some extent.

When experience can be kept proprietary, it can be a potent force in industry change. If the firm is not gaining experience the fastest, it must prepare strategically to either practice rapid imitation or build strategic advantages in other areas besides cost. Doing the latter requires the firm to adopt generic strategies of differentiation or focus.

6. EXPANSION (OR CONTRACTION) IN SCALE

A growing industry is, by definition, increasing its total scale. This growth is usually accompanied by increases in the absolute size of the leading firms in the industry, and firms gaining market share must be increasing in size even more rapidly. Increasing scale in in-dustry and firm has a number of implications for industry structure. First, it tends to widen the set of available strategies in ways that of-ten lead to increased economies of scale and capital requirements in the industry. For example, it may allow larger firms to substitute capital for labor, adopt production methods subject to greater econ-omies of scale, establish captive distribution channels or a captive service organization and utilize national advertising. Increasing scale also can make it feasible for an outsider to enter the industry with substantial competitive advantages by being the first to adopt such changes.8

The way in which increasing scale operates on industry structure is illustrated by light aircraft in the 1960s and early 1970s. In this in-dustry, growth allowed Cessna (the industry leader) to shift its pro-duction process from job shop to quasi–mass production. This change resulted in a cost advantage for Cessna because it reaped economies of scale in mass production as yet unavailable to its major competitors. If Cessna’s two leading competitors also reach the scale to begin more capital–intensive mass production, barriers to entry into the industry by outsiders will increase markedly.

Another consequence of industry growth is that strategies of vertical integration tend to become more feasible, and increased ver-tical integration tends to elevate barriers. Increasing industry scale also means that suppliers to the industry are selling it larger volumes of goods, and the industry’s customers as a group are purchasing larger quantities. To the extent that individual suppliers or buyers are increasing their sales or purchases as well, there may be tempta-tions for them to begin forward or backward integration into the in-dustry. Whether or not integration actually occurs, the bargaining power of suppliers or buyers will go up.

There may also be a tendency for large industry scale to attract new entrants, who can make it tougher for existing leaders, particu-larly if the entrants are large, established firms. Many large firms will enter a market only after it has reached a significant absolute size (to justify the fixed costs of entry and make a material contribu-tion to their overall sales), even though they have been probable po-tential entrants right from the industry’s birth as a result of skills or assets they bring from their existing businesses. For example, in the recreational vehicle industry the initial entrants were new firms started from scratch and relatively small diversifying mobile home producers whose production process was similar to that of making recreational vehicles. As the industry got large enough, big farm equipment and automotive companies began to enter. These firms had ample resources for competing in recreational vehicles drawn from their existing operations, but they left it to the smaller firms to develop the market and prove that a significant market existed be-fore they entered.

7. CHANGES IN INPUT COSTS AND EXCHANGE RATES

Every industry uses a variety of inputs to its manufacturing, dis-tribution, and marketing process. Changes in the cost or quality of these inputs can affect industry structure. The important classes of input costs subject to change are the following:

- wage rates (encompassing the full costs of labor);

- material costs;

- cost of capital;

- communication costs (including media);

- transportation costs.

The most straightforward effect is in increasing or decreasing the cost (and price) of the product, thereby affecting demand. For example, the cost of producing movies has risen quite markedly in recent years. This rise is squeezing independent producers relative to well-financed movie companies, particularly since movie tax shelters have been circumscribed by 1976 tax legislation. This development has cut a major avenue of financing for independent producers.

Changes in wage rates or capital costs may change the shape of the industry’s cost curve, altering economies of scale or promoting substitution of capital for labor. Escalating labor costs in service calls and deliveries are fundamentally affecting strategy in many in-dustries. Changes in the cost of communication or transportation can promote reorganization of production, which affects entry bar-riers. Changes in communication costs may lead to use of different cost-effective selling media (and thereby changes in the level of prod-uct differentiation), changed distribution arrangements, and so on. In addition, changes in transportation costs can shift geographic market boundaries, which either increases or decreases the effective number of competitors in the industry.

Exchange rate fluctuations can also have a profound effect on industry competition. The devaluation of the dollar against the yen and many European currencies, for example, has triggered signifi-cant shifts in position in many industries since 1971.

8. PRODUCT INNOVATION

A major source of industry structural change is technological innovations of various types and origins. Innovation in product is one important type. Product innovation can widen the market and hence promote industry growth and/or it can enhance product dif–ferentiation. Product innovation also can have indirect effects. The process of rapid product introduction, and associated needs for high marketing costs, may itself create mobility barriers. Innovations may require new marketing, distribution, or manufacturing methods that change economies of scale or other mobility barriers. Signifi-cant product change can also nullify buyer experience and hence im-pact purchasing behavior.

Product innovations can come from outside or inside the indus-try. Color television was pioneered by RCA, a leader in black and white television. However, electronic calculators were introduced by electronics companies and not mechanical calculator or slide rule producers. Thus forecasting product innovations involves examining possible external sources. Many innovations flow vertically, origi-nated by customers and suppliers, where the industry is an important customer or source of inputs.

An example of the influence of product innovation on structure is the introduction of the digital watch. Economies of scale in pro-ducing digital watches are greater than those in producing most con-ventional watch varieties. Competing in digital watches also requires large capital investments and an entirely new technological base compared to conventional watches. Thus mobility barriers and other aspects of the structure of the watch industry are changing rapidly.

10. MARKETING INNOVATION

Like innovations in product, those in marketing can influence industry structure directly through increasing demand. Break-throughs in the use of advertising media, new marketing themes or channels, and so forth can allow reaching new consumers or reduc-ing price sensitivity (raising product differentiation). For example, movie companies have boosted demand by advertising movies on tele-vision. The discovery of new channels of distribution can similarly widen demand or raise product differentiation; innovations in mar-keting that make it more efficient can lower the cost of the product.

Innovations in marketing and distribution also have effects on other elements of industry structure. New forms of marketing can be subject to increased or decreased economies of scale and hence affect mobility barriers. For example, the shift in marketing wine from low-key magazine advertising to network television has raised the mobility barriers in the wine industry. Marketing innovations can also shift power relative to buyers, and affect the balance of fixed and variable costs and hence the volatility of rivalry.

11. PROCESS INNOVATION

The final class of innovation that can change industry structure is that in the manufacturing process or methods. Innovations can make the process more or less capital intensive, increase or decrease economies of scale, change the proportion of fixed costs, increase or decrease vertical integration, affect the process of accumulating ex-perience, and so on—all of which affect industry structure. Innova-tions that increase scale economies or extend the experience curve beyond the size of national markets can lead to industry globaliza-tion (see Chapter 13).

An example of the way in which interacting evolutionary proc-esses can trigger manufacturing changes is found in changes occur-ring in the computer service bureau business in 1977. Computer serv-ice bureaus provide computer power and a library of programs to a wide variety of users, including those in business, education, and fi-nancial institutions. Traditionally service bureaus have been local or regional organizations serving primarily smaller businesses with sim-ple computer packages in areas like accounting and payroll. How-ever, a substitute product, the minicomputer, has made cheap com-puter power easily accessible to even small organizations. As a result, forces have been set in motion which are promoting the devel-opment of large regional and national service bureaus. First, more sophisticated programs are being developed to differentiate the serv-ice bureau from the minicomputer, which require substantial invest–ments. The economies of spreading such investments over a large number of users are promoting concentration. Second, pressure to offer computer power at low cost is putting a premium on efficient use of facilities. This development is adding to the impetus toward national companies to take advantage of time zone changes to make use of off-hours capacity. Third, computer technology continues to increase in complexity, raising technological barriers to establish a service bureau at least in the short run. So all these forces built up in the evolutionary process have led to a change in the manufacturing process of the leading service bureaus.

Manufacturing innovations that change structure can come from outside the industry as well as from within. Developments in computerized machine tools and other manufacturing equipment by equipment suppliers, for example, may lead to increased scale econ-omies in production in an industry. The 1950s innovations by fiber-glass producers that led to the use of fiberglass in boats greatly re-duced the difficulty of designing and building pleasure boats. This reduction in entry barriers triggered the entry of a large number of new companies into the industry with disastrous consequences for profits, many failing between 1960 and 1962 as the industry under-went a shake-out. In the metal container industry, suppliers of steel expended substantial resources to help defend steel cans against the inroads of the aluminum can through innovations reducing the gauge of steel and techniques for lower-cost can manufacture. All these examples suggest that the firm must broaden its view of tech-nological change beyond industry boundaries.

12. STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN ADJACENT INDUSTRIES

Since the structure of suppliers’ and customers’ industries af-fects their bargaining power with an industry, changes in their struc-ture have potentially important consequences for industry evolution. For example, there has been substantial chain-store development in the retailing of clothing and hardware in the 1960s and 1970s. As the structure of retailing has become concentrated, the retailers’ bar-gaining power with their supplying industries has increased. Apparel makers are getting squeezed by retailers, who are ordering closer and closer to the selling season and demanding other concessions. Manu-facturers’ marketing and promotional strategies have had to adjust, and concentration in apparel manufacturing is forecast to increase. The mass merchandising revolution in retailing generally has had similar effects on many other industries (watches, small appliances, toiletries).

Whereas changes in the concentration or vertical integration of adjacent industries attract the most attention, more subtle changes in the methods of competition in the adjacent industries can often be just as important in affecting evolution. For example, in the 1950s and early 1960s record retailers dropped the policy of allowing con-sumers to play records in the store. The effects of this change in the adjacent recording industry proved to be profound. Since the con-sumer could no longer sample records in the store, what radio sta-tions played became critical to record sales. However, because ad-vertising rates were becoming increasingly tied to sustained audience size, radio stations were shifting to the “Top 40″ format, that is, re-peatedly playing only the leading songs. It became extremely diffi-cult to get a new, unproven record aired on the radio. The change in retailing created a powerful new element for the recording indus-try—radio stations—which changed the strategic requirements for success. It also forced the recording industry to purchase advertising time for new record releases on radio stations, the only sure way to assure that new recordings were played, and generally increased bar-riers into the recording industry.

The importance of changes in the structure of adjacent indus-tries points to the need to diagnose and prepare for structural evolu–tion in supplying and buying industries, just as in the industry itself.

13. GOVERNMENT POLICY CHANGE

Government influences can have a significant and tangible im-pact on industry structural change, the most direct through full-blown regulation of such key variables as entry into the industry, competitive practices, or profitability. For example, pending na-tional health insurance legislation with cost-plus reimbursement will fundamentally affect profit potential in the proprietary hospital and clinical laboratory industries. Requirements for licensing, an inter-mediate form of government regulation, tend to restrict entry and thereby provide an entry barrier protecting existing firms. Changes in government pricing regulation also can have a fundamental im-pact on industry structure. A current example is the profound conse-quences that have accompanied the shift from legally fixed commis-sions to negotiated commissions in securities transactions. Fixed commissions created a price umbrella for securities firms and shifted competition from price to service and research. Ending fixed com-missions has shifted competition to price and resulted in mass exit from the industry, either through outright failure or mergers. Mobil-ity barriers in the new environment are dramatically increased. Gov-ernment actions can also dramatically increase or decrease the likeli-hood of international competition (see Chapter 13).

Less direct forms of government influence on industry structure occur through the regulation of product quality and safety, environ-mental quality, and tariffs or foreign investments. The effect of many new product quality and environmental regulations, though they surely achieve some desirable social objectives, is to raise capi-tal requirements, elevate economies of scale through the imposition of research and testing requirements, and otherwise worsen the posi-tion of smaller firms in an industry and raise barriers facing new firms.

An example of the impact of quality regulation is in the security guard industry. Criticism has mounted over the lack of training that companies give their guards in the use of weapons, arrest techniques, and so on, and legislation to require mandatory training of a speci-fied duration is on the horizon. Although such a requirement will be easily met by the larger companies, many smaller companies may be severely hurt by the increased overhead and the need to compete for higher skilled employees.

14. ENTRY AND EXIT

Entry clearly affects industry structure, particularly entry by es-tablished firms from other industries. Firms enter an industry be-cause they perceive opportunities for growth and profits that exceed the costs of entry (or of surmounting mobility barriers).9 Based on case studies of many industries, industry growth seems to be the most important signal to outsiders that there are future profits to be made, even though this can often be a poor assumption. Entry also follows particularly visible indications of future growth, such as reg-ulatory changes, product innovations, and so on. For example, the energy crisis and recent proposed legislation to provide federal sub-sidy have evoked rapid entry into solar heating even though demand for solar heating is still quite low.

The entry into an industry (by either acquisition or internal de-velopment) of an established firm is often a major driving force for industry structural change.10 Established firms from other markets generally have skills or resources that can be applied to change com-petition in the new industry; in fact this often provides a major moti-vation for their entry decision. Such skills and resources are very often different from those of existing firms, and their application in many cases changes the industry’s structure. Also, firms in other markets may be able to perceive opportunities to change industry structure better than existing firms because they have no ties to his–torical strategies and may be in a position to be more aware of tech-nological changes occurring outside the industry that can be applied to competing in it.

An example will serve to illustrate. In 1960, the U.S. wine in-dustry was composed primarily of small family firms producing pre-mium wines and selling them in regional markets. There was little advertising or promotion, few firms had national distribution, and the competitive focus of most firms in the industry was clearly on the production of fine wines.” Profits in the industry were modest. In the mid-1960s, however, a number of large consumer marketing companies (e.g., Heublein, United Brands) either entered the indus-try through internal development or purchased existing wine produc-ers. They began investing heavily in consumer advertising and pro-motion for both low-cost and premium brands. Since several of these firms had national distribution through liquor stores because they produced other alcoholic beverages, they rapidly expanded dis-tribution for their brands nationally. Frequent introduction of new brand names became the rule in the industry, and many new prod-ucts were introduced at the low end of the quality spectrum, which old-line companies had generally downplayed while they developed a name for U.S. wines. The profitability of the industry leaders was excellent. Thus the entry of a different type of firm into the U.S. wine industry has caused or at least speeded up a significant structur-al change in the industry, and one which the early family-controlled participants in the industry had neither the skills, the resources, nor the inclination to cause themselves.

Exit changes industry structure by reducing the number of firms and possibly increasing the dominance of the leading ones. Firms ex-it because they no longer perceive the possibility of earning returns on their investment that exceed the opportunity cost of capital. The exit process is impeded by exit barriers (Chapter 1), which worsen the position of remaining, healthier firms and may lead to price war-fare and other competitive outbreaks. Increases in concentration and the ability of an industry’s profitability to climb in response to in-dustry structural shifts also will be impeded by the presence of exit barriers.

The evolutionary processes are a tool for predicting industry changes. Each evolutionary process is the basis of a key strategic question. For example, the potential impact of government regula-tory change on an industry’s structure means that a company must ask itself, “Are there any government actions on the horizon that may influence some element of the structure of my industry? If so, what does the change do for my relative strategic position, and how can I prepare to deal with it effectively now?” A similar question can be formulated for each of the other evolutionary processes dis-cussed above. The set of questions that result should be asked on a repeated basis, perhaps even formally through the strategic planning process.

Furthermore, each evolutionary process identifies a number of key strategic signals, or pieces of key strategic information, for which the firm must constantly scan its environment. The entry of an established firm from another industry, a key development affecting a substitute product, and so on should cause a red light to go in the minds of executives charged with maintaining the strategic health of a business. This red light should trigger a chain of analysis to predict the significance of the change for the industry and the appropriate response.

Finally, it is important to note that learning, experience, in-creasing market size, and several other of the processes discussed above will be operating even if there are no important distinct events to signal this. The implication is that regular attention should be given to structural changes that may be resulting from these hidden processes.

Source: Porter Michael E. (1998), Competitive Strategy_ Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press; Illustrated edition.