Movement originating with Soren Kierkegaard(1813-1855) and continuing later with Karl Jaspers(1883-1969), Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973), Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), and various others, though it has had little influence in English-speaking philosophy. Fyodor Dostoevsky (1812-1881) and Friedrich Nietzsche(1844-1900) are sometimes included.

The main idea is to distinguish the kind of being possessed by humans – called Dasein (Heidegger) or être-pour-soi (Sartre) – from that possessed by ordinary objects (Stre-en-soi for Sartre).

The former, which is partly an actual condition of humans and partly something to be pursued, is essentially open-ended and free from determination by any already existing essence: ‘existence precedes essence’. Hence the emphasis on freedom, choice and responsibility, evasion of which by relapsing into a ‘thing-like’ state (or trying to do so) is Sartrian ‘bad faith’.

Consciousness of this total open-endedness leads to dread (despair, anguish, angst, angoisse). In studying being, existentialists have been influenced by phenomenology.

Source:

N Langiulli, ed., The Existentialist Tradition (1971); selections, those from Abbagnano, Buber, Marcel, and Sartre being perhaps the most accessible

Etymology

The term existentialism (French: L’existentialisme) was coined by the French Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel in the mid-1940s.[17][18][19] When Marcel first applied the term to Jean-Paul Sartre, at a colloquium in 1945, Sartre rejected it.[20] Sartre subsequently changed his mind and, on October 29, 1945, publicly adopted the existentialist label in a lecture to the Club Maintenant in Paris, published as L’existentialisme est un humanisme (Existentialism is a Humanism), a short book that helped popularize existentialist thought.[21] Marcel later came to reject the label himself in favour of Neo-Socratic, in honor of Kierkegaard’s essay “On The Concept of Irony”.

Some scholars argue that the term should be used only to refer to the cultural movement in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s associated with the works of the philosophers Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Albert Camus.[6] Others extend the term to Kierkegaard, and yet others extend it as far back as Socrates.[22] However, it is often identified with the philosophical views of Sartre.[6]

Definitional issues and background

The labels existentialism and existentialist are often seen as historical conveniences in as much as they were first applied to many philosophers long after they had died. While existentialism is generally considered to have originated with Kierkegaard, the first prominent existentialist philosopher to adopt the term as a self-description was Sartre. Sartre posits the idea that “what all existentialists have in common is the fundamental doctrine that existence precedes essence,” as the philosopher Frederick Copleston explains.[23] According to philosopher Steven Crowell, defining existentialism has been relatively difficult, and he argues that it is better understood as a general approach used to reject certain systematic philosophies rather than as a systematic philosophy itself.[6] In a lecture delivered in 1945, Sartre described existentialism as “the attempt to draw all the consequences from a position of consistent atheism.”[24] For others, existentialism need not involve the rejection of God, but rather “examines mortal wo/man’s search for meaning in a meaningless universe,” considering less “What is the good life?” (to feel, be, or do, good), instead asking “What is life good for?”[25]

Although many outside Scandinavia consider the term existentialism to have originated from Kierkegaard,[who?] it is more likely that Kierkegaard adopted this term (or at least the term “existential” as a description of his philosophy) from the Norwegian poet and literary critic Johan Sebastian Cammermeyer Welhaven.[26] This assertion comes from two sources. The Norwegian philosopher Erik Lundestad refers to the Danish philosopher Fredrik Christian Sibbern. Sibbern is supposed to have had two conversations in 1841, the first with Welhaven and the second with Kierkegaard. It is in the first conversation that it is believed that Welhaven came up with “a word that he said covered a certain thinking, which had a close and positive attitude to life, a relationship he described as existential”.[27] This was then brought to Kierkegaard by Sibbern.

The second claim comes from the Norwegian historian Rune Slagstad, who claims to prove that Kierkegaard himself said the term “existential” was borrowed from the poet. He strongly believes that it was Kierkegaard himself who said that “Hegelians do not study philosophy “existentially;” to use a phrase by Welhaven from one time when I spoke with him about philosophy.”[28]

Concepts

Existence precedes essence

Sartre argued that a central proposition of existentialism is that existence precedes essence, which means that the most important consideration for individuals is that they are individuals—independently acting and responsible, conscious beings (“existence”)—rather than what labels, roles, stereotypes, definitions, or other preconceived categories the individuals fit (“essence”). The actual life of the individuals is what constitutes what could be called their “true essence” instead of an arbitrarily attributed essence others use to define them. Human beings, through their own consciousness, create their own values and determine a meaning to their life.[29] This view is in contradiction to Aristotle and Aquinas who taught that essence precedes individual existence.[citation needed] Although it was Sartre who explicitly coined the phrase, similar notions can be found in the thought of existentialist philosophers such as Heidegger, and Kierkegaard:

The subjective thinker’s form, the form of his communication, is his style. His form must be just as manifold as are the opposites that he holds together. The systematic eins, zwei, drei is an abstract form that also must inevitably run into trouble whenever it is to be applied to the concrete. To the same degree as the subjective thinker is concrete, to that same degree his form must also be concretely dialectical. But just as he himself is not a poet, not an ethicist, not a dialectician, so also his form is none of these directly. His form must first and last be related to existence, and in this regard he must have at his disposal the poetic, the ethical, the dialectical, the religious. Subordinate character, setting, etc., which belong to the well-balanced character of the esthetic production, are in themselves breadth; the subjective thinker has only one setting—existence—and has nothing to do with localities and such things. The setting is not the fairyland of the imagination, where poetry produces consummation, nor is the setting laid in England, and historical accuracy is not a concern. The setting is inwardness in existing as a human being; the concretion is the relation of the existence-categories to one another. Historical accuracy and historical actuality are breadth. Søren Kierkegaard (Concluding Postscript, Hong pp. 357–358)

Some interpret the imperative to define oneself as meaning that anyone can wish to be anything. However, an existentialist philosopher would say such a wish constitutes an inauthentic existence – what Sartre would call “bad faith”. Instead, the phrase should be taken to say that people are defined only insofar as they act and that they are responsible for their actions. Someone who acts cruelly towards other people is, by that act, defined as a cruel person. Such persons are themselves responsible for their new identity (cruel persons). This is opposed to their genes, or human nature, bearing the blame.

As Sartre said in his lecture Existentialism is a Humanism: “man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards”. The more positive, therapeutic aspect of this is also implied: a person can choose to act in a different way, and to be a good person instead of a cruel person.[30]

Jonathan Webber interprets Sartre’s usage of the term essence not in a modal fashion, i.e. as necessary features, but in a teleological fashion: “an essence is the relational property of having a set of parts ordered in such a way as to collectively perform some activity”.[31]:3[6] For example, it belongs to the essence of a house to keep the bad weather out, which is why it has walls and a roof. Humans are different from houses because – unlike houses – they don’t have an inbuilt purpose: they are free to choose their own purpose and thereby shape their essence; thus, their existence precedes their essence.[31]:1–4

Sartre is committed to a radical conception of freedom: nothing fixes our purpose but we ourselves, our projects have no weight or inertia except for our endorsement of them.[32][33] Simone de Beauvoir, on the other hand, holds that there are various factors, grouped together under the term sedimentation, that offer resistance to attempts to change our direction in life. Sedimentations are themselves products of past choices and can be changed by choosing differently in the present, but such changes happen slowly. They are a force of inertia that shapes the agent’s evaluative outlook on the world until the transition is complete.[31]:5,9,66

Sartre’s definition of existentialism was based on Heidegger’s magnum opus Being and Time (1927). In the correspondence with Jean Beaufret later published as the Letter on Humanism, Heidegger implied that Sartre misunderstood him for his own purposes of subjectivism, and that he did not mean that actions take precedence over being so long as those actions were not reflected upon.[34] Heidegger commented that “the reversal of a metaphysical statement remains a metaphysical statement”, meaning that he thought Sartre had simply switched the roles traditionally attributed to essence and existence without interrogating these concepts and their history.[35]

The absurd

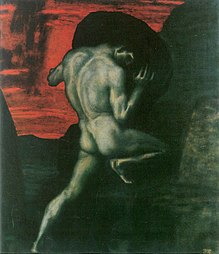

Sisyphus, the symbol of the absurdity of existence, painting by Franz Stuck (1920)

The notion of the absurd contains the idea that there is no meaning in the world beyond what meaning we give it. This meaninglessness also encompasses the amorality or “unfairness” of the world. This can be highlighted in the way it opposes the traditional Abrahamic religious perspective, which establishes that life’s purpose is the fulfillment of God’s commandments.[36] This is what gives meaning to people’s lives. To live the life of the absurd means rejecting a life that finds or pursues specific meaning for man’s existence since there is nothing to be discovered. According to Albert Camus, the world or the human being is not in itself absurd. The concept only emerges through the juxtaposition of the two; life becomes absurd due to the incompatibility between human beings and the world they inhabit.[36] This view constitutes one of the two interpretations of the absurd in existentialist literature. The second view, first elaborated by Søren Kierkegaard, holds that absurdity is limited to actions and choices of human beings. These are considered absurd since they issue from human freedom, undermining their foundation outside of themselves.[37]

The absurd contrasts with the claim that “bad things don’t happen to good people”; to the world, metaphorically speaking, there is no such thing as a good person or a bad person; what happens happens, and it may just as well happen to a “good” person as to a “bad” person.[38] Because of the world’s absurdity, anything can happen to anyone at any time and a tragic event could plummet someone into direct confrontation with the absurd. The notion of the absurd has been prominent in literature throughout history. Many of the literary works of Kierkegaard, Samuel Beckett, Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Eugène Ionesco, Miguel de Unamuno, Luigi Pirandello,[39][40][41][42] Sartre, Joseph Heller, and Camus contain descriptions of people who encounter the absurdity of the world.

It is because of the devastating awareness of meaninglessness that Camus claimed in The Myth of Sisyphus that “there is only one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide”. Although “prescriptions” against the possible deleterious consequences of these kinds of encounters vary, from Kierkegaard’s religious “stage” to Camus’ insistence on persevering in spite of absurdity, the concern with helping people avoid living their lives in ways that put them in the perpetual danger of having everything meaningful break down is common to most existentialist philosophers. The possibility of having everything meaningful break down poses a threat of quietism, which is inherently against the existentialist philosophy.[43] It has been said that the possibility of suicide makes all humans existentialists. The ultimate hero of absurdism lives without meaning and faces suicide without succumbing to it.

Everything is very open with a very clear clarification of the issues. It was definitely informative.

Hey! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and tell you I really enjoy reading your articles. Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that go over the same subjects? Thanks!

Adding a Forumer?„? community to your website is a great way to get return visitors. Create a forum and see how a loyal community of users will propel your

Yo, simply changed into alert to your post via Yahoo, and found that its truly informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate when you continue this in future. Lots of other people might be benefited out of your writing. Thankx

My sis informed me about your website and the way great it is. She’s proper, I am actually impressed with the writing and slick design. It appears to me you’re just scratching the floor by way of what you may accomplish, but you’re off to an excellent begin!