The title of a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), general theory of employment, interest and money represents a major contribution to modern economic thought.

It attacked classical economics and put forward important theories on the consumption function, aggregate demand, the multiplier, marginal efficiency of capital, liquidity preference and expectations.

Also see: absolute income hypothesis, aggregate demand theory, demand for money theory, disequilibrium theory, theory of income determination, marginal efficiency of capital, natural and warranted rates of growth, own rate of interest, paradox of thrift

Source:

J M Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York, 1936)

Keynes’s aims in the General Theory

The central argument of The General Theory is that the level of employment is determined not by the price of labour, as in classical economics, but by the level of aggregate demand. If the total demand for goods at full employment is less than the total output, then the economy has to contract until equality is achieved. Keynes thus denied that full employment was the natural result of competitive markets in equilibrium.

In this he challenged the conventional (‘classical’) economic wisdom of his day. In a letter to his friend George Bernard Shaw on New Year’s Day, 1935, he wrote:

I believe myself to be writing a book on economic theory which will largely revolutionize — not I suppose, at once but in the course of the next ten years — the way the world thinks about its economic problems. I can’t expect you, or anyone else, to believe this at the present stage. But for myself I don’t merely hope what I say,— in my own mind, I’m quite sure.[2]

The first chapter of the General theory (only half a page long) has a similarly radical tone:

I have called this book the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, placing the emphasis on the prefix general. The object of such a title is to contrast the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory of the subject, upon which I was brought up and which dominates the economic thought, both practical and theoretical, of the governing and academic classes of this generation, as it has for a hundred years past. I shall argue that the postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case, the situation which it assumes being a limiting point of the possible positions of equilibrium. Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience.

Summary of the General Theory

Keynes’s main theory (including its dynamic elements) is presented in Chapters 2-15, 18, and 22, which are summarised here. A shorter account will be found in the article on Keynesian economics. The remaining chapters of Keynes’s book contain amplifications of various sorts and are described later in this article.

Book I: Introduction

The first book of the The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is a repudiation of Say’s Law. The classical view for which Keynes made Say a mouthpiece held that the value of wages was equal to the value of the goods produced, and that the wages were inevitably put back into the economy sustaining demand at the level of current production. Hence, starting from full employment, there cannot be a glut of industrial output leading to a loss of jobs. As Keynes put it on p. 18, “supply creates its own demand”.

Stickiness of wages in money terms

Say’s Law depends on the operation of a market economy. If there is unemployment (and if there are no distortions preventing the employment market from adjusting to it) then there will be workers willing to offer their labour at less than the current wage levels, leading to downward pressure on wages and increased offers of jobs.

The classics held that full employment was the equilibrium condition of an undistorted labour market, but they and Keynes agreed in the existence of distortions impeding transition to equilibrium. The classical position had generally been to view the distortions as the culprit[3] and to argue that their removal was the main tool for eliminating unemployment. Keynes on the other hand viewed the market distortions as part of the economic fabric and advocated different policy measures which (as a separate consideration) had social consequences which he personally found congenial and which he expected his readers to see in the same light.

The distortions which have prevented wage levels from adapting downwards have lain in employment contracts being expressed in monetary terms; in various forms of legislation such as the minimum wage and in state-supplied benefits; in the unwillingness of workers to accept reductions in their income; and in their ability through unionisation to resist the market forces exerting downward pressure on them.

Keynes accepted the classical relation between wages and the marginal productivity of labour, referring to it on page 5[4] as the “first postulate of classical economics” and summarising it as saying that “The wage is equal to the marginal product of labour”.

The first postulate can be expressed in the equation y'(N) = W/p, where y(N) is the real output when employment is N, and W and p are the wage rate and price rate in money terms (and hence W/p is the wage rate in real terms). A system can be analysed on the assumption that W is fixed (i.e. that wages are fixed in money terms) or that W/p is fixed (i.e. that they are fixed in real terms) or that N is fixed (e.g. if wages adapt to ensure full employment). All three assumptions had at times been made by classical economists, but under the assumption of wages fixed in money terms the ‘first postulate’ becomes an equation in two variables (N and p), and the consequences of this had not been taken into account by the classical school.

Keynes proposed a ‘second postulate of classical economics’ asserting that the wage is equal to the marginal disutility of labour. This is an instance of wages being fixed in real terms. He attributes the second postulate to the classics subject to the qualification that unemployment may result from wages being fixed by legislation, collective bargaining, or ‘mere human obstinacy’ (p6), all of which are likely to fix wages in money terms.

Outline of Keynes’s theory

Keynes’s economic theory is based on the interaction between demands for saving, investment, and liquidity (i.e. money). Saving and investment are necessarily equal, but different factors influence decisions concerning them. The desire to save, in Keynes’s analysis, is mostly a function of income: the wealthier people are, the more wealth they will seek to put aside. The profitability of investment, on the other hand, is determined by the relation between the return available to capital and the interest rate. The economy needs to find its way to an equilibrium in which no more money is being saved than will be invested, and this can be accomplished by contraction of income and a consequent reduction in the level of employment.

In the classical scheme it is the interest rate rather than income which adjusts to maintain equilibrium between saving and investment; but Keynes asserts that the rate of interest already performs another function in the economy, that of equating demand and supply of money, and that it cannot adjust to maintain two separate equilibria. In his view it is the monetary role which wins out. This is why Keynes’s theory is a theory of money as much as of employment: the monetary economy of interest and liquidity interacts with the real economy of production, investment and consumption.

Book II: Definitions and ideas

The choice of units[edit]

Keynes sought to allow for the lack of downwards flexibility of wages by constructing an economic model in which the money supply and wage rates were externally determined (the latter in money terms), and in which the main variables were fixed by the equilibrium conditions of various markets in the presence of these facts.

Many of the quantities of interest, such as income and consumption, are monetary. Keynes often expresses such quantities in wage units (Chapter 4): to be precise, a value in wage units is equal to its price in money terms divided by W, the wage (in money units) per man-hour of labour. Keynes generally writes a subscript w on quantities expressed in wage units, but in this account we omit the w. When, occasionally, we use real terms for a value which Keynes expresses in wage units we write it in lower case (e.g. y rather than Y).

As a result of Keynes’s choice of units, the assumption of sticky wages, though important to the argument, is largely invisible in the reasoning. If we want to know how a change in the wage rate would influence the economy, Keynes tells us on p. 266 that the effect is the same as that of an opposite change in the money supply.

The identity of saving and investment[edit]

The relationship between saving and investment, and the factors influencing their demands, play an important role in Keynes’s model. Saving and investment are considered to be necessarily equal for reasons set out in Chapter 6 which looks at economic aggregates from the viewpoint of manufacturers. The discussion is intricate, considering matters such as the depreciation of machinery, but is summarised on p. 63:

Provided it is agreed that income is equal to the value of current output, that current investment is equal to the value of that part of current output which is not consumed, and that saving is equal to the excess of income over consumption… the equality of saving and investment necessarily follows.

This statement incorporates Keynes’s definition of saving, which is the normal one.

Book III: The propensity to consume

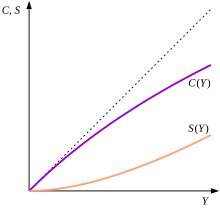

Keynes’s propensities to consume and to save as functions of income Y.

Book III of the General Theory is given over to the propensity to consume, which is introduced in Chapter 8 as the desired level of expenditure on consumption (for an individual or aggregated over an economy). The demand for consumer goods depends chiefly on the income Y and may be written functionally as C(Y). Saving is that part of income which is not consumed, so the propensity to save S(Y) is equal to Y–C(Y). Keynes discusses the possible influence of the interest rate r on the relative attractiveness of saving and consumption, but regards it as ‘complex and uncertain’ and leaves it out as a parameter.

His seemingly innocent definitions embody an assumption whose consequences will be considered later. Since Y is measured in wage units, the proportion of income saved is considered to be unaffected by the change in real income resulting from a change in the price level while wages stay fixed. Keynes acknowledges that this is undesirable in Point (1) of Section II.

In Chapter 9 he provides a homiletic enumeration of the motives to consume or not to do so, finding them to lie in social and psychological considerations which can be expected to be relatively stable, but which may be influenced by objective factors such as ‘changes in expectations of the relation between the present and the future level of income’ (p95).

The marginal propensity to consume and the multiplier[edit]

The marginal propensity to consume, C'(Y), is the gradient of the purple curve, and the marginal propensity to save S'(Y) is equal to 1–C'(Y). Keynes states as a ‘fundamental psychological law’ (p96) that the marginal propensity to consume will be positive and less than unity.

Chapter 10 introduces the famous ‘multiplier’ through an example: if the marginal propensity to consume is 90%, then ‘the multiplier k is 10; and the total employment caused by (e.g.) increased public works will be ten times the employment caused by the public works themselves’ (pp116f). Formally Keynes writes the multiplier as k=1/S'(Y). It follows from his ‘fundamental psychological law’ that k will be greater than 1.

Keynes’s account is not clear until his economic system has been fully set out (see below). In Chapter 10 he describes his multiplier as being related to the one introduced by R. F. Kahn in 1931.[5] The mechanism of Kahn’s multiplier lies in an infinite series of transactions, each conceived of as creating employment: if you spend a certain amount of money, then the recipient will spend a proportion of what he or she receives, the second recipient will spend a further proportion again, and so forth. Keynes’s account of his own mechanism (in the second para of p. 117) makes no reference to infinite series. By the end of the chapter on the multiplier, he uses his much quoted “digging holes” metaphor, against laissez-faire. In his provocation Keynes argues that “If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the banknotes up again” (…), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing”.

Oh my goodness! a tremendous article dude. Thanks Nonetheless I am experiencing subject with ur rss . Don’t know why Unable to subscribe to it. Is there anyone getting similar rss downside? Anybody who is aware of kindly respond. Thnkx