Muhammad[a] (Arabic: مُحَمَّد; c. 570 – 8 June 632 CE)[b] was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam.[c] According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and other prophets.[2][3][4] He is believed to be the Seal of the Prophets within Islam. Muhammad united Arabia into a single Muslim polity, with the Quran as well as his teachings and practices forming the basis of Islamic religious belief.

Muhammad was born in approximately 570 CE in Mecca.[1] He was the son of Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib and Amina bint Wahb. His father, Abdullah, the son of Quraysh tribal leader Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim, died a few months before Muhammad’s birth. His mother Amina died when he was six, leaving Muhammad an orphan.[5] He was raised under the care of his grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, and paternal uncle, Abu Talib.[6] In later years, he would periodically seclude himself in a mountain cave named Hira for several nights of prayer. When he was 40, circa 610 CE, Muhammad reported being visited by Gabriel in the cave[1] and receiving his first revelation from God. In 613,[7] Muhammad started preaching these revelations publicly,[8] proclaiming that “God is One”, that complete “submission” (islām) to God is the right way of life (dīn),[9] and that he was a prophet and messenger of God, similar to the other prophets in Islam.[10][3][11]

Muhammad’s followers were initially few in number, and experienced hostility from Meccan polytheists for 13 years. To escape ongoing persecution, he sent some of his followers to Abyssinia in 615, before he and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina (then known as Yathrib) later in 622. This event, the Hijra, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar, also known as the Hijri Calendar. In Medina, Muhammad united the tribes under the Constitution of Medina. In December 629, after eight years of intermittent fighting with Meccan tribes, Muhammad gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and marched on the city of Mecca. The conquest went largely uncontested and Muhammad seized the city with little bloodshed. In 632, a few months after returning from the Farewell Pilgrimage, he fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam.[12][13]

The revelations (each known as Ayah — literally, “Sign [of God]”) that Muhammad reported receiving until his death form the verses of the Quran, regarded by Muslims as the verbatim “Word of God” on which the religion is based. Besides the Quran, Muhammad’s teachings and practices (sunnah), found in the Hadith and sira (biography) literature, are also upheld and used as sources of Islamic law.

Names and appellations

The name Muhammad (/mʊˈhæməd, –ˈhɑːməd/[14]) means “praiseworthy” in Arabic. It appears four times in the Quran.[15] The Quran also addresses Muhammad in the second person by various appellations; prophet, messenger, servant of God (‘abd), announcer (bashir),[16] witness (shahid),[17] bearer of good tidings (mubashshir), warner (nathir),[18] reminder (mudhakkir),[19] one who calls [unto God] (dā’ī),[20] light personified (noor),[21] and the light-giving lamp (siraj munir).[22]

Sources of biographical information

Quran

The Quran is the central religious text of Islam. Muslims believe it represents the words of God revealed by the archangel Gabriel to Muhammad.[23][24][25] The Quran, however, provides minimal assistance for Muhammad’s chronological biography; most Quranic verses do not provide significant historical context.[26][27]

Early biographies

Important sources regarding Muhammad’s life may be found in the historic works by writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Muslim era (AH – 8th and 9th century CE).[28] These include traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad, which provide additional information about his life.[29]

The earliest written sira (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) is Ibn Ishaq’s Life of God’s Messenger written c. 767 CE (150 AH). Although the original work was lost, this sira survives as extensive excerpts in works by Ibn Hisham and to a lesser extent by Al-Tabari.[30][31] However, Ibn Hisham wrote in the preface to his biography of Muhammad that he omitted matters from Ibn Ishaq’s biography that “would distress certain people”.[32] Another early history source is the history of Muhammad’s campaigns by al-Waqidi (death 207 AH), and the work of Waqidi’s secretary Ibn Sa’d al-Baghdadi (death 230 AH).[28]

Many scholars accept these early biographies as authentic, though their accuracy is unascertainable.[30] Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between traditions touching legal matters and purely historical events. In the legal group, traditions could have been subject to invention while historic events, aside from exceptional cases, may have been only subject to “tendential shaping”.[33]

Hadith

Other important sources include the hadith collections, accounts of verbal and physical teachings and traditions attributed to Muhammad. Hadiths were compiled several generations after his death by Muslims including Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi, Abd ar-Rahman al-Nasai, Abu Dawood, Ibn Majah, Malik ibn Anas, al-Daraqutni.[34][35]

Some Western academics cautiously view the hadith collections as accurate historical sources.[34] Scholars such as Madelung do not reject the narrations which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.[36] Muslim scholars on the other hand typically place a greater emphasis on the hadith literature instead of the biographical literature, since hadiths maintain a traditional chain of transmission (isnad); the lack of such a chain for the biographical literature makes it unverifiable in their eyes.[37]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being Mecca and Medina. Medina was a large flourishing agricultural settlement, while Mecca was an important financial center for many surrounding tribes.[38] Communal life was essential for survival in the desert conditions, supporting indigenous tribes against the harsh environment and lifestyle. Tribal affiliation, whether based on kinship or alliances, was an important source of social cohesion.[39] Indigenous Arabs were either nomadic or sedentary. Nomadic groups constantly traveled seeking water and pasture for their flocks, while the sedentary settled and focused on trade and agriculture. Nomadic survival also depended on raiding caravans or oases; nomads did not view this as a crime.[40]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, gods or goddesses were viewed as protectors of individual tribes, their spirits associated with sacred trees, stones, springs and wells. As well as being the site of an annual pilgrimage, the Kaaba shrine in Mecca housed 360 idols of tribal patron deities. Three goddesses were worshipped, in some places as daughters of Allah: Allāt, Manāt and al-‘Uzzá. Monotheistic communities existed in Arabia, including Christians and Jews.[d] Hanifs – native pre-Islamic Arabs who “professed a rigid monotheism”[41] – are also sometimes listed alongside Jews and Christians in pre-Islamic Arabia, although scholars dispute their historicity.[42][43] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad himself was a Hanif and one of the descendants of Ishmael, son of Abraham,[e] although no known evidence exists for a historical Abraham or Ishmael, and the links are based solely on tradition instead of historical records.[44]

The second half of the sixth century was a period of political disorder in Arabia and communication routes were no longer secure.[45] Religious divisions were an important cause of the crisis.[46] Judaism became the dominant religion in Yemen while Christianity took root in the Persian Gulf area.[46] In line with broader trends of the ancient world, the region witnessed a decline in the practice of polytheistic cults and a growing interest in a more spiritual form of religion. While many were reluctant to convert to a foreign faith, those faiths provided intellectual and spiritual reference points.[46]

During the early years of Muhammad’s life, the Quraysh tribe to which he belonged became a dominant force in western Arabia.[47] They formed the cult association of hums, which tied members of many tribes in western Arabia to the Kaaba and reinforced the prestige of the Meccan sanctuary.[48] To counter the effects of anarchy, Quraysh upheld the institution of sacred months during which all violence was forbidden, and it was possible to participate in pilgrimages and fairs without danger.[48] Thus, although the association of hums was primarily religious, it also had important economic consequences for the city.[48]

Life

Meccan years

Childhood and early life

Abu al-Qasim Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim[49] was born in Mecca[50] about the year 570,[1] and his birthday is believed to be in the month of Rabi’ al-awwal.[51] He belonged to the Quraysh tribe’s Banu Hashim clan, which was one of the more distinguished families in Mecca, although the clan seemed to experience a lack of prosperity during his early years.[11][f] Islamic tradition states that Muhammad’s birth year coincided with Yemeni King Abraha‘s unsuccessful attempt to conquer Mecca.[52] Recent studies, however, challenge this notion, as other evidence suggests that the expedition, if it had occured, would have transpired substantially before Muhammad’s birth.[1][53][54][55][56][57] Later Muslim scholars presumably linked Abraha’s renowned name to the narrative of Muhammad’s birth to elucidate the unclear passage about “the men of elephants” in Quran 105:1-5.[53] The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity deems the tale of Abraha’s war elephant expedition as a myth.[54]

Muhammad’s father, Abdullah, died almost six months before he was born.[59] According to Islamic tradition, soon after birth he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert, as desert life was considered healthier for infants; some western scholars reject this tradition’s historicity.[60] Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, and her husband until he was two years old. At the age of six, Muhammad lost his biological mother Amina to illness and became an orphan.[60][61] For the next two years, until he was eight years old, Muhammad was under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, of the Banu Hashim clan until his death. He then came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib, the new leader of the Banu Hashim.[6] According to Islamic historian William Montgomery Watt there was a general disregard by guardians in taking care of weaker members of the tribes in Mecca during the 6th century, “Muhammad’s guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seem to have been declining at that time.”[62]

In his teens, Muhammad accompanied his uncle on Syrian trading journeys to gain experience in commercial trade.[62] Islamic tradition states that when Muhammad was either nine or twelve while accompanying the Meccans’ caravan to Syria, he met a Christian monk or hermit named Bahira who is said to have foreseen Muhammad’s career as a prophet of God.[63]

Little is known of Muhammad during his later youth as available information is fragmented, making it difficult to separate history from legend.[62] He reportedly became a merchant and “was involved in trade between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.”[64] Muhammad was also known as al-Amin (lit. ’faithful’) when he was young. Historians differ as to whether the name was given by people as a reflection of his nature,[65] or was simply a given name from his parents, i.e. a masculine form of his mother’s name “Amina”.[11] His reputation attracted a proposal in 595 from Khadijah, a successful businesswoman. Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.[64]

Several years later, according to a narration collected by historian Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad was involved with a well-known story about setting the Black Stone in place in the wall of the Kaaba in 605 CE. The Black Stone, a sacred object, was removed during renovations to the Kaaba. The Meccan leaders could not agree which clan should return the Black Stone to its place. They decided to ask the next man who came through the gate to make that decision; that man was the 35-year-old Muhammad. This event happened five years before the first revelation by Gabriel to him. He asked for a cloth and laid the Black Stone in its center. The clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and together carried the Black Stone to the right spot, then Muhammad laid the stone, satisfying the honor of all.[66][67]

Beginnings of the Quran

Muhammad began to pray alone in a cave named Hira on Mount Jabal al-Nour, near Mecca, for several weeks every year.[68][69] Islamic tradition states that during his visit to the cave in 610 CE, the angel Gabriel appeared before him, showing a cloth with Quranic verses on it and instructing him to read. When Muhammad confessed his illiteracy, Gabriel choked him forcefully, nearly suffocating him, and repeated the command. As Muhammad reiterated his inability to read, Gabriel choked him again in a similar manner. This sequence took place once more before Gabriel finally recited the verses, allowing Muhammad to memorize them.[70][71][72] These verses later constituted Quran 96:1-5.[73]

Recite in the name of your Lord who created—Created man from a clinging substance. Recite, and your Lord is the most Generous—Who taught by the pen—Taught man that which he knew not.

— Quran 96:1–5

The experience terrified Muhammad, but he was immediately reassured by his wife Khadija and her Christian cousin Waraqa ibn Nawfal.[74] Khadija instructed Muhammad to let her know if Gabriel returned. When he appeared during their private time, Khadija conducted tests by having Muhammad sit on her left thigh, right thigh, and lap, inquiring Muhammad if the being was still present each time. After Khadija removed her clothes with Muhammad on her lap, he reported that Gabriel left at that very moment. Khadija thus told him to rejoice as she concluded it was not a Satan but an angel visiting him.[75][76][74]

Muhammad’s demeanor during his moments of inspiration frequently led to allegations from his contemporaries that he was under the influence of a jinn, a soothsayer, or a magician, suggesting that his experiences during these events bore resemblance to those associated with such figures widely recognized in ancient Arabia. Nonetheless, these enigmatic seizure events might have served as persuasive evidence for his followers regarding the divine origin of his revelations. Some historians posit that the graphic descriptions of Muhammad’s condition in these instances are likely genuine, as they are improbable to have been concocted by later Muslims.[77][78]

Shortly after Waraqa’s death, the revelations ceased for a period, causing Muhammad great distress and thoughts of suicide.[72][g] On one occasion, he reportedly climbed a mountain intending to jump off. However, upon reaching the peak, Gabriel appeared to him, affirming his status as the true Messenger of Allah. This encounter soothed Muhammad, and he returned home. Later, when there was another long break between revelations, he repeated this action, but Gabriel intervened similarly, calming him and causing him to return home.[79][80]

Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages.[81] According to the Quran, one of the main roles of Muhammad is to warn the unbelievers of their eschatological punishment (Quran 38:70,[82] Quran 6:19).[83] Occasionally the Quran did not explicitly refer to Judgment day but provided examples from the history of extinct communities and warns Muhammad’s contemporaries of similar calamities.[84] Muhammad did not only warn those who rejected God’s revelation, but also dispensed good news for those who abandoned evil, listening to the divine words and serving God. Muhammad’s mission also involves preaching monotheism: The Quran commands Muhammad to proclaim and praise the name of his Lord and instructs him not to worship idols or associate other deities with God.[84]

The key themes of the early Quranic verses included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of the dead, God’s final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in Hell and pleasures in Paradise, and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were simple and few in numbers: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not exposing new-born girls to die in the desert, which was sometimes done at the time out of poverty.[11]

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad’s wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.[85] She was followed by Muhammad’s ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zaid.[85]

Onset of frictions with the Quraysh

Around 613, Muhammad began to preach to the public.[8][86] Initially, he had no serious opposition from the inhabitants of Mecca, who were indifferent to his proselytizing activities, but when he started to attack their beliefs, tensions arose.[87][88][89][90] The Quraysh challenged him to perform miracles, such as bringing forth springs of water, but he declined, reasoning that the regularities of nature already served as sufficient proof of God’s majesty. Some later satirised his lack of success by wondering why God had not bestowed treasure upon him. Others called on him to visit Paradise and return with tangible parchment scrolls of the Qur’an. But the Qur’an claims that its very existence in the world is already an extraordinary proof.[91]

According to Amr ibn al-As, several of the Quraysh gathered at Hijr and discussed how they had never faced such serious problems as they were facing from Muhammad. They said that he had derided their culture, denigrated their ancestors, scorned their faith, shattered their community, and cursed their gods. Some time later, Muhammad came, kissing the Black Stone and performing the ritual tawaf. As Muhammad passed by them, they reportedly said hurtful things to him. The same happened when he passed by them a second time. On his third pass, Muhammad stopped and said, “Will you listen to me, O Quraysh? By Him (God), who holds my life in His hand, I bring you slaughter.” They fell silent and told him to go home, saying that he was not a violent man. The next day, a number of Quraysh approached him, asking if he had said what they had heard from their companions. He answered yes, and one of them seized him by his cloak. Abu Bakr intervened, tearfully saying, “Would you kill a man for saying God is my Lord?” And they left him.[92][93][94]

The Quraysh attempted to entice Muhammad to quit preaching by giving him admission to the merchants’ inner circle as well as an advantageous marriage, but he refused both of the offers.[95] A delegation of them then, led by the leader of the Makhzum clan, known by the Muslims as Abu Jahl, went to Muhammad’s uncle Abu Talib, head of the Hashim clan and Muhammad’s caretaker, giving him an ultimatum:[96]

“By God, we can no longer endure this vilification of our forefathers, this derision of our traditional values, this abuse of our gods. Either you stop Muhammad yourself, Abu Talib, or you must let us stop him. Since you yourself take the same position as we do, in opposition to what he’s saying, we will rid you of him.”[97][98]

Abu Talib politely dismissed them at first, thinking it was just a heated talk. But as Muhammad grew more vocal, Abu Talib requested Muhammad to not burden him beyond what he could bear. To which Muhammad wept and replied that he would not stop even if they put the sun in his right hand and the moon in his left. When he turned around, Abu Talib called him and said, “Come back nephew, say what you please, for by God I will never give you up on any account.”[99][100]

While a group of Muslims were praying in a ravine, some Quraysh ran into them and blamed them for what they were doing. One of the Muslims, Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, then took a camel’s jawbone and struck a Quraysh, splitting his head open, in what is reported to be the first blood shed in Islam.[101][102]

Islamic traditions record at great length the persecution and mistreatment that Muhammad and his followers later underwent from the Meccan polytheists, but the accounts are more or less obscure and open to various equally uncertain interpretations.[103] Some of them include the stories of a slave identified as Sumayya bint Khayyat, who was said to have been killed by her master Abu Jahl with a spear, and Bilal, also a slave, who reportedly having a big stone placed on his chest by his master Umayya ibn Khalaf because they both refused to leave Islam;[104] Bilal was eventually bought by Abu Bakr or traded for a slave of his own who had not yet embraced Islam.[105] Alford T. Welch et al. point out that the Qur’an is virtually silent on such episodes that the traditions report as major events in Muhammad’s Meccan years, despite its frequent references to the major events of his life following the Hijrah.[103]

The Quraysh consulted the Jews

The Quraysh tasked Nadr ibn al-Harith and Uqba ibn Abi Mu’ayt with seeking the opinions of Jewish rabbis in Medina regarding Muhammad. The rabbis advised them to ask Muhammad three questions: recount the tale of young men who ventured forth in the first age; narrate the story of a traveler who reached both the eastern and western ends of the earth; and provide details about the Spirit. If Muhammad answered correctly, they stated, he would be a Prophet; otherwise, he would be a liar. When they returned to Mecca and asked Muhammad the questions, he told them he would provide the answers the next day. However, 15 days passed without a response from his God, leading to gossip among the Meccans and causing Muhammad distress. At some point later, Gabriel came to Muhammad and provided him with the answers.[106][107]

In response to the first query, the Quran tells an intriguing yet somewhat vague story about a group of men sleeping in a cave (Quran 18:9–25), which scholars generally link to the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. For the second query, the Quran speaks of Dhu al-Qarnayn, literally “he of the two horns” (Quran 18:93–99), a tale that academics widely associate with the Alexander Romance.[108][109] As for the third query, concerning the nature of the spirit, the Quranic revelation asserted that it was beyond human comprehension. Neither the Jews who devised the questions nor the Quraysh who posed them to Muhammad converted to Islam upon receiving the answers.[107] Nadr and Uqba were later executed on Muhammad’s orders after the Battle of Badr, while other captives were held for ransom. As Uqba pleaded, “But who will take care of my children, Muhammad?” Muhammad responded, “Hell!”[110][111][112][113]

Migration to Abyssinia and the incident of Satanic Verses

In 615, fearful that his followers would be seduced from their religion,[114] Muhammad sent some of them to emigrate to the Abyssinian Kingdom of Aksum and found a small colony under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[11] Among those who departed were Umm Habiba, the daughter of one of the Quraysh chiefs, Abu Sufyan, and her husband.[115] The Quraysh then sent two men to retrieve them. Because leatherwork at the time was highly prized in Abyssinia, they gathered a lot of skins and transported them there so they could distribute some to each of the kingdom’s generals. But the king firmly rejected their request.[116]

While Tabari and Ibn Hisham mentioned only one migration to Abyssinia, there were two sets according to Ibn Sa’d. Of these two, the majority of the first group returned to Mecca before the event of Hijra, while majority of the second group remained in Abyssinia at the time, and went directly to Medina after the event of Hijra. These accounts agree that persecution played a major role in Muhammad sending them there. According to historian W. M. Watt, the episodes were more complex than the traditional accounts suggest, he proposes that there were divisions within the embryonic Muslim community, and that they likely went there to trade in competition with the prominent merchant families of Mecca. In Urwa’s letter preserved by Tabari, these emigrants returned after the conversion to Islam of a number of individuals in positions such as Hamza and Umar.[11]

Tabari also, among many others,[117] recorded that Muhammad was desperate, hoping for an accommodation with his tribe. So, while he was in the presence of a number of Quraysh, after delivering verses mentioning three of their favorite deities (Quran 53:19-20), Satan put upon his tongue two short verses: “These are the high flying ones / whose intercession is to be hoped for.” This led to a general reconciliation between Muhammad and the Meccans, and the Muslims in Abyssinia began to return home. However, the next day, Muhammad retracted these verses at the behest of Gabriel, claiming that they had been cast by Satan to his tongue and God had abrogated them. Instead, verses that revile those goddesses were then revealed.[118][h][i] The returning Muslims thus had to make arrangements for clan protection before they could re-enter Mecca.[11][119]

This satanic verses incident was reported en masse and recorded by virtually every compiler of a major biography of Muhammad in the first two centuries of Islam, which according to them corresponds to Quran 22:52. But since the rise of the hadith movement and systematic theology with its new doctrines, including the isma, which claimed that Muhammad was infallible and thus could not be fooled by Satan, the historical memory of the early community has been reevaluated. And as of the 20th century AD, Muslim scholars unanimously rejected this incident.[117] On the other hand, most European biographers of Muhammad recognize the veracity of this incident of satanic verses on the basis of the criterion of embarrassment. Historian Alfred T. Welch proposes that the period of Muhammad’s turning away from strict monotheism was likely far longer but was later encapsulated in a story that made it much shorter and imputed Satan as the culprit.[11]

In 616 (or 617), the leaders of Makhzum and Banu Abd-Shams, two important Quraysh clans, declared a public boycott against Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, to pressure it into withdrawing its protection of Muhammad. The boycott lasted for three years but eventually collapsed as it failed in its objective.[120][121]

Attempt to establish himself in Ta’if

After the deaths of Khadija, Muhammad’s wealthy wife, who had provided him with financial and emotional support,[122] and Abu Talib, his guardian, Muhammad’s position became increasingly hopeless.[11] He went to Ta’if to try to establish himself in the city and gain aid and protection against the Meccans,[123][124] but he was met with a response: “If you are truly a prophet, what need do you have of our help? If God sent you as his messenger, why doesn’t He protect you? And if Allah wished to send a prophet, couldn’t He have found a better person than you, a weak and fatherless orphan?”[125] Realizing his efforts were in vain, Muhammad asked the people of Ta’if to keep the matter a secret, fearing that this would embolden the hostility of the Quraysh against him. However, instead of accepting his request, they threw him with stones, injuring his limbs.[126]

On Muhammad’s return journey to Mecca, news of the events in Ta’if had reached the ears of Abu Jahl, and he said, “They did not allow him to enter Ta’if, so let us deny him entry to Mecca as well.” Knowing the gravity of the situation, Muhammad asked a passing horseman to deliver a message to Akhnas ibn Shariq, a member of his mother’s clan, requesting his protection so that he could enter in safety. But Akhnas declined, saying that he was only a confederate of the house of Quraysh. Muhammad then sent a message to Suhayl ibn Amir, who similarly declined on the basis of tribal principle. Finally, Muhammad dispatched someone to ask Mut’im ibn ‘Adiy, the chief of the Banu Nawfal. Mut’im agreed, and after equipping himself, he rode out in the morning with his sons and nephews to accompany Muhammad to the city. When Abu Jahl saw him, he asked if Mut’im was simply giving him protection or if he had already converted to his religion. Mut’im replied, “Granting him protection, of course.” Then Abu Jahl said, “We will protect whomever you protect.”[127]

Isra’ and Mi’raj

It is at this low point in Muhammad’s life that the accounts in the Sira lay out the famous Isra’ and Mi’raj. Nowadays, Isra’ is believed by Muslims to be the journey of Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem, while Mi’raj is from Jerusalem to the heavens.[11] There is considered no substantial basis for the Mi’raj in the Quran, as the Quran does not address it directly and emphasizes that Muhammad was not given any miracles other than the Quran.[129]

According to Quran 17:1, Muhammad’s night journey took him from the sacred place of prayer to the furthest place of prayer. While the Kaaba is widely accepted as “the sacred place of prayer,” there is disagreement among Islamic traditions as to the identity of the “furthest place of prayer.” One modern scholarly view maintains that the oldest tradition regarded “the furthest place of prayer” as the heavenly prototype of the Kaaba, so the night journey was then a direct journey from Mecca through the heavens to the celestial Kaaba. A later tradition, however, identified “the furthest place of prayer” as the Bayt al-Maqdis, which is commonly believed to be in Jerusalem. Over time, these two traditions were reconciled, presenting Muhammad’s journey as from Mecca to Jerusalem and then from there to the heavens.[130]

The dating of the events also differs from account to account. Ibn Sa’d recorded that Muhammad’s Mi’raj took place first, from near the Kaaba to the heavens, on the 27th of Ramadan, 18 months before the Hijrah, while the Isra’ from Mecca to Bayt al-Maqdis took place on the 17th night of the Last Rabi’ul before the hijrah. As is well known, these two stories were later combined into one. In Ibn Hisham’s account, the Isra’ came first and then the Mi’raj, and he put these stories before the deaths of Khadija and Abu Talib. On the other hand, al-Tabari only included the story of Muhammad’s ascension from the sanctuary in Mecca to “the earthly heaven”. Tabari placed this story at the beginning of Muhammad’s public ministry, between his account of Khadija becoming “the first to believe in the Messenger of God” and his account of “the first male to believe in the Messenger of God.”[11]

Hijrah

Having lost all hope of winning converts among his fellow townspeople, Muhammad limited his efforts to non-Meccans who attended fairs or made pilgrimages.[131] In 620, his uncle al-Abbas, who had not yet converted to Islam, introduced him to political elite of the Banu Khazraj and Banu Aws in Medina and coordinated a meeting at Aqaba.[132] The two clans had been in conflict against one another for years, with each trying to court the support of the Jewish tribes in the area.[133] In order to readjust their political relationship, they sought a political leader from outside,[134] and considered Muhammad, with his authority based on religious claims, would be in a better position to act as an impartial arbiter than any resident of Medina.[135] Seven or eight men of them then sat at Aqaba listening intently to what he had to say.[131]

After a year, they returned with five more people and converted to Islam. Muhammad promised them that Islam would pave the way for them to live harmoniously with the Jews.[131] Following his failure in Taif, Muhammad acted with prudence and sent an agent to accompany the group back to Medina, ostensibly to spread his religious teachings.[135] The next year, they returned to Aqaba with 73 men and two women. Al-Abbas said to those who were present:

This, my kinsman, dwells among us in honor and safety. His clan (the Banu Hashim) will defend him—both those who are converts and those who still adhere to their ancestral faith—but he prefers to seek protection from you. Therefore, consider the matter well and count the cost. If you are resolved and able to defend him, well; but if you doubt your ability, at once abandon the design.[136]

Then Muhammad himself spoke to those people:

I invite your allegiance on the basis that you protect me as you would your women and children.[137]

In which they agreed. After that, Muhammad commanded the Muslims in Mecca to migrate to Medina.[138] This event is known as the Hijrah which basically means severing of kinship ties.[139][140] Some Muslims were held back by their families from leaving but in the end there were no Muslims left in Mecca.[141] Twentieth-century Pakistani Muslim scholar Fazlur Rahman said that the Muslims were expelled from Mecca and their property seized.[142]

Being alarmed at the departure, according to tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate Muhammad. With the help of Ali, Muhammad fooled the Meccans watching him, and secretly slipped away from the town with Abu Bakr.[143] By 622, Muhammad emigrated to the flourishing agricultural oasis of Medina. The Meccan Muslims who undertook the migration with him were called the muhajirun, while the Medinans who accepted Islam and aided the emigrants were dubbed the ansar.[11]

Medinan years

Medina, located over 200 miles to the north of Mecca, is a lush oasis.[144] According to Muslim sources, the city was established by Jews who had survived the revolt against the Romans.[145] While agriculture was far from being the domain of the Arab tribes, the Jews were outstanding farmers, cultivating the land in the oases.[145] There were reportedly around 20 Jewish tribes residing in the city, with the three most prominent being Banu Nadir, Banu Qaynuqa and Banu Qurayza.[146] In time, Arab tribes from southern Arabia migrated to the city and settled down alongside the Jewish community,[145] and gradually replaced their position of hegemony.[133] The Arab tribes consisted of Banu Aws and Banu Khazraj, both collectively known as Banu Qayla.[147] Before 620, there had been fighting among the two Arab tribes for almost a hundred years,[144] with each of them attempting to court the assistance of the Jewish tribes,[133] causing the latter sometimes also had to fight each other.[144] In 622, when Muhammad came to the city, the Jewish tribes were allied as subordinates to the two Arab tribes.[148]

Early life in the city

Ibn Ishaq, following his narration of the hijrah, maintains that Muhammad penned a text now referred to as the Constitution of Medina and divulges its assumed content without supplying any isnad or corroboration.[149] The appellation is generally deemed imprecise, as the text neither established a state nor enacted Quranic statutes,[150] but rather addressed tribal matters.[151] While scholars from both the West and the Muslim world agree on the text’s authenticity, disagreements persist on whether it was a treaty or a unilateral proclamation by Muhammad, the number of documents it comprised, the primary parties, the specific timing of its creation (or that of its constituent parts), whether it was drafted before or after Muhammad’s removal of the three leading Jewish tribes of Medina, and the proper approach to translating it.[149][152]

Initially confident that the Jewish residents of Medina would recognize him as a Prophet, Muhammad focused intently on gaining converts within their community during his early tenure in the city. Yet, as these endeavors failed to yield results, the previously congenial attitude of both him and the Quran toward the Jews soured.[153][154] This led to the reorientation of the qibla from Jerusalem to the Kaaba.[155] The situation was opposite with the pagan peoples of Medina, among whom Islam spread rather smoothly, especially following Sa’d ibn Muadh’s conversion.[156]

Beginning of armed conflict

Subsequent to obtaining a divine instruction to battle the polytheists, Muhammad dispatched his followers to perform raids on the Quraysh’s trading caravans. Certain Meccan followers of his were reluctant to partake, as it would mean attacking their own tribespeople. This vexed Muhammad, resulting in the revelation of Quran verse 2:216, among others, which asserts that fighting is good and has been made obligatory for them.[157] The initial six forays ended in failure, but the seventh endeavor, launched during a pagan holy month in which shedding blood was forbidden, culminated in triumph.[158][159] When the bountiful plunder was being brought back to him in Medina,[157] Muhammad was met with censure from the locals. He contended that his followers had misconstrued his command, and he postponed the allocation of the spoils until a verse was ultimately revealed, legitimizing the attack.[158] Consequently, Muhammad took a fifth of the spoils.[160]

Permission has been given to those who are being fought, because they were wronged. And indeed, Allah is competent to give them victory. Those who have been evicted from their homes without right—only because they say, “Our Lord is Allah.” And were it not that Allah checks the people, some by means of others, there would have been demolished monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques in which the name of Allah is much mentioned. And Allah will surely support those who support Him. Indeed, Allah is Powerful and Exalted in Might.

— Quran (22:39–40)

Two months hence, a grand Quraysh trade caravan, representing the investments of all Meccans, traveled home from Gaza. Upon hearing the news, Muhammad swiftly mobilized his followers to intercept it at Badr.[161] Alerted to Muhammad’s intentions, Abu Sufyan, who led the caravan, hastily dispatched messengers to Mecca for aid. Roughly 950 men journeyed to Badr in response. After the caravan narrowly escaped through a risky route, some reinforcements opted to withdraw,[162] while others remained and camouflaged their camp behind a hill.[163] Muhammad, upon discovering their presence through their water carrier, strategically covered all wells with sand, reserving one for his forces. This bold maneuver compelled the lingering Meccans to engage in battle for water.[164][163]

The battle commenced with individual duels between warriors from both sides, leading to the deaths of several prominent Meccans, including Abu Jahl,[165] Muhammad’s most bitter adversary. The conflict then escalated into a chaotic melee.[166] Although not participating in the combat, Muhammad inspired his followers with the promise of paradise if they died fighting. Many of the Quraysh reluctant in killing their own kin, and just prior to midday, they succumbed to panic and ran away.[167] The battle concluded with the Quraysh suffering 49 to 70 losses, while the Muslims had 14 casualties.[168] The Muslims obtained considerable war spoils and a number of prisoners. Umar desired that all of them be slain, yet Muhammad resolved that ransom must be requested first, and afterwards, they could execute any for whom no one was willing to pay.[167]

Upon his return to Medina, Muhammad immediately worked to solidify his authority. He instructed the removal of Asma bint Marwan, who had criticized him in poetry.[169] One of his followers executed her while she slept with her children, the youngest still nursing in her arms. Upon learning of the deed, Muhammad lauded the act as a service to God and his Messenger.[170][169][171] Shortly after, he called upon his followers to end the life of the centenarian poet Abu Afak.[169][170] Simultaneously, Muhammad employed poets like Hassan ibn Thabit to circulate his propaganda among the tribes. When inquired if he could shield Muhammad from his foes, Ibn Thabit is reported to have extended his tongue and claimed there was no defense against his verbal prowess.[169]

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of three main Jewish tribes.[11] Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hejaz.[11]

Conflict with Mecca

The Meccans were eager to avenge their defeat. To maintain economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been reduced at Badr.[172] In the ensuing months, the Meccans sent ambush parties to Medina while Muhammad led expeditions against tribes allied with Mecca and sent raiders onto a Meccan caravan.[173] Abu Sufyan gathered an army of 3000 men and set out for an attack on Medina.[174]

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army’s presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, a dispute arose over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many senior figures suggested it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of the heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying crops, and huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the younger Muslims and readied the Muslim force for battle. Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (the location of the Meccan camp) and fought the Battle of Uhud on 23 March 625.[175][176] Although the Muslim army had the advantage in early encounters, lack of discipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat; 75 Muslims were killed, including Hamza, Muhammad’s uncle who became one of the best known martyrs in the Muslim tradition. The Meccans did not pursue the Muslims; instead, they marched back to Mecca declaring victory. The announcement is probably because Muhammad was wounded and thought dead. When they discovered that Muhammad lived, the Meccans did not return due to false information about new forces coming to his aid. The attack had failed to achieve their aim of completely destroying the Muslims.[177][178] The Muslims buried the dead and returned to Medina that evening. Questions accumulated about the reasons for the loss; Muhammad delivered Quranic verses 3:152 indicating that the defeat was twofold: partly a punishment for disobedience, partly a test for steadfastness.[179]

Abu Sufyan directed his effort towards another attack on Medina. He gained support from the nomadic tribes to the north and east of Medina; using propaganda about Muhammad’s weakness, promises of booty, memories of Quraysh prestige and through bribery.[180] Muhammad’s new policy was to prevent alliances against him. Whenever alliances against Medina were formed, he sent out expeditions to break them up.[180] Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Medina, and reacted in a severe manner.[181] One example is the assassination of Ka’b ibn al-Ashraf, a chieftain of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir. Al-Ashraf went to Mecca and wrote poems that roused the Meccans’ grief, anger and desire for revenge after the Battle of Badr.[182][183] Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Banu Nadir from Medina[184] forcing their emigration to Syria; he allowed them to take some possessions, as he was unable to subdue the Banu Nadir in their strongholds. The rest of their property was claimed by Muhammad in the name of God as it was not gained with bloodshed. Muhammad surprised various Arab tribes, individually, with overwhelming force, causing his enemies to unite to annihilate him. Muhammad’s attempts to prevent a confederation against him were unsuccessful, though he was able to increase his own forces and stopped many potential tribes from joining his enemies.[185]

Battle of the Trench

With the help of the exiled Banu Nadir, the Quraysh military leader Abu Sufyan mustered a force of 10,000 men. Muhammad prepared a force of about 3,000 men and adopted a form of defense unknown in Arabia at that time; the Muslims dug a trench wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman the Persian. The siege of Medina began on 31 March 627 and lasted two weeks.[186] Abu Sufyan’s troops were unprepared for the fortifications, and after an ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to return home.[j] The Quran discusses this battle in sura Al-Ahzab, in verses 33:9–27.[187] During the battle, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, located to the south of Medina, entered into negotiations with Meccan forces to revolt against Muhammad. Although the Meccan forces were swayed by suggestions that Muhammad was sure to be overwhelmed, they desired reassurance in case the confederacy was unable to destroy him. No agreement was reached after prolonged negotiations, partly due to sabotage attempts by Muhammad’s scouts.[188] After the coalition’s retreat, the Muslims accused the Banu Qurayza of treachery and besieged them in their forts for 25 days. The Banu Qurayza eventually surrendered; all the men apart from a few converts to Islam were beheaded, while the women and children were enslaved.[189][190]

In the siege of Medina, the Meccans exerted the available strength to destroy the Muslim community. The failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria vanished.[191] Following the Battle of the Trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north, both ended without any fighting.[11] While returning from one of these journeys (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad’s wife. Aisha was exonerated from accusations when Muhammad announced he had received a revelation confirming Aisha’s innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses (sura 24, An-Nur).[192]

Truce of Hudaybiyyah

“In your name, O God!

This is the treaty of peace between Muhammad Ibn Abdullah and Suhayl Ibn Amr. They have agreed to allow their arms to rest for ten years. During this time each party shall be secure, and neither shall injure the other; no secret damage shall be inflicted, but honesty and honour shall prevail between them. Whoever in Arabia wishes to enter into a treaty or covenant with Muhammad can do so, and whoever wishes to enter into a treaty or covenant with the Quraysh can do so. And if a Qurayshite comes without the permission of his guardian to Muhammad, he shall be delivered up to the Quraysh; but if, on the other hand, one of Muhammad’s people comes to the Quraysh, he shall not be delivered up to Muhammad. This year, Muhammad, with his companions, must withdraw from Mecca, but next year, he may come to Mecca and remain for three days, yet without their weapons except those of a traveller; the swords remaining in their sheaths.”

—The statement of the treaty of Hudaybiyyah[193]

Although Muhammad had delivered Quranic verses commanding the Hajj,[194] the Muslims had not performed it due to Quraysh enmity. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to prepare for a pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision when he was shaving his head after completion of the Hajj.[195] Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh dispatched 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, enabling his followers to reach al-Hudaybiyya just outside Mecca.[196] According to Watt, although Muhammad’s decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream, he was also demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam did not threaten the prestige of the sanctuaries, that Islam was an Arabian religion.[196]

Negotiations commenced with emissaries traveling to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad called upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the “Pledge of Acceptance” or the “Pledge under the Tree”. News of Uthman’s safety allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh.[196][198] The main points of the treaty included: cessation of hostilities, the deferral of Muhammad’s pilgrimage to the following year, and agreement to send back any Meccan who emigrated to Medina without permission from their protector.[196]

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the treaty. However, the Quranic sura “Al-Fath” (The Victory) assured them that the expedition must be considered a victorious one.[199] It was later that Muhammad’s followers realized the benefit behind the treaty. These benefits included the requirement of the Meccans to identify Muhammad as an equal, cessation of military activity allowing Medina to gain strength, and the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the pilgrimage rituals.[11]

After signing the truce, Muhammad assembled an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar, known as the Battle of Khaybar. This was possibly due to housing the Banu Nadir who were inciting hostilities against Muhammad, or to regain prestige from what appeared as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya.[174][200] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date is given variously in the sources).[11][201][202] He sent messengers (with letters) to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Khosrau of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others.[201][202] In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad directed his forces against the Arabs on Transjordanian Byzantine soil in the Battle of Mu’tah.[203]

Final years

Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyyah was enforced for two years.[204][205] The tribe of Banu Khuza’a had good relations with Muhammad, whereas their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had allied with the Meccans.[204][205] A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuza’a, killing a few of them.[204][205] The Meccans helped the Banu Bakr with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting.[204] After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were: either the Meccans would pay blood money for the slain among the Khuza’ah tribe, they disavow themselves of the Banu Bakr, or they should declare the truce of Hudaybiyyah null.[206]

The Meccans replied that they accepted the last condition.[206] Soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Sufyan to renew the Hudaybiyyah treaty, a request that was declined by Muhammad.

Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[207] In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with 10,000 Muslim converts. With minimal casualties, Muhammad seized control of Mecca.[208] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who were “guilty of murder or other offences or had sparked off the war and disrupted the peace”.[209] Some of these were later pardoned.[210] Most Meccans converted to Islam and Muhammad proceeded to destroy all the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba.[211] According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad personally spared paintings or frescos of Mary and Jesus, but other traditions suggest that all pictures were erased.[212] The Quran discusses the conquest of Mecca.[187][213]

Conquest of Arabia

Following the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were raising an army double the size of Muhammad’s. The Banu Hawazin were old enemies of the Meccans. They were joined by the Banu Thaqif (inhabiting the city of Ta’if) who adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans.[214] Muhammad defeated the Hawazin and Thaqif tribes in the Battle of Hunayn.[11]

In the same year, Muhammad organized an attack against northern Arabia because of their previous defeat at the Battle of Mu’tah and reports of hostility adopted against Muslims. With great difficulty he assembled 30,000 men; half of whom on the second day returned with Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy, untroubled by the damning verses which Muhammad hurled at them. Although Muhammad did not engage with hostile forces at Tabuk, he received the submission of some local chiefs of the region.[11][215]

He also ordered the destruction of any remaining pagan idols in Eastern Arabia. The last city to hold out against the Muslims in Western Arabia was Taif. Muhammad refused to accept the city’s surrender until they agreed to convert to Islam and allowed men to destroy the statue of their goddess Al-Lat.[216][217][218]

A year after the Battle of Tabuk, the Banu Thaqif sent emissaries to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many bedouins submitted to Muhammad to safeguard against his attacks and to benefit from the spoils of war.[11] However, the bedouins were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain independence: namely their code of virtue and ancestral traditions. Muhammad required a military and political agreement according to which they “acknowledge the suzerainty of Medina, to refrain from attack on the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religious levy.”[219]

Farewell pilgrimage

In 632, at the end of the tenth year after migration to Medina, Muhammad completed his first true Islamic pilgrimage, setting precedent for the annual Great Pilgrimage, known as Hajj.[11] On the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah Muhammad delivered his Farewell Sermon, at Mount Arafat east of Mecca. In this sermon, Muhammad advised his followers not to follow certain pre-Islamic customs. For instance, he said a white has no superiority over a black, nor a black any superiority over a white except by piety and good action.[220] He abolished old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system and asked for old pledges to be returned as implications of the creation of the new Islamic community. Commenting on the vulnerability of women in his society, Muhammad asked his male followers to “be good to women, for they are powerless captives (awan) in your households. You took them in God’s trust, and legitimated your sexual relations with the Word of God, so come to your senses people, and hear my words …” He told them that they were entitled to discipline their wives but should do so with kindness. He addressed the issue of inheritance by forbidding false claims of paternity or of a client relationship to the deceased and forbade his followers to leave their wealth to a testamentary heir. He also upheld the sacredness of four lunar months in each year.[221][222] According to Sunni tafsir, the following Quranic verse was delivered during this event: “Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you”.[223][11] According to Shia tafsir, it refers to the appointment of Ali ibn Abi Talib at the pond of Khumm as Muhammad’s successor, this occurring a few days later when Muslims were returning from Mecca to Medina.[k]

Death and tomb

A few months after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with fever, head pain, and weakness. He died on Monday, 8 June 632, in Medina, at the age of 62 or 63, in the house of his wife Aisha.[224] With his head resting on Aisha’s lap, he asked her to dispose of his last worldly goods (seven coins), then spoke his final words:

“O God, forgive me and have mercy on me; and let me join the highest companion.”[225][226][227]

— Muhammad

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, Muhammad’s death may be presumed to have been caused by Medinan fever exacerbated by physical and mental fatigue.[228]

Muhammad was buried where he died in Aisha’s house.[11][229][230] During the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, al-Masjid an-Nabawi (the Mosque of the Prophet) was expanded to include the site of Muhammad’s tomb.[231] The Green Dome above the tomb was built by the Mamluk sultan Al Mansur Qalawun in the 13th century, although the green color was added in the 16th century, under the reign of Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[232] Among tombs adjacent to that of Muhammad are those of his companions (Sahabah), the first two Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar, and an empty one that Muslims believe awaits Jesus.[230][233][234]

When Saud bin Abdul-Aziz took Medina in 1805, Muhammad’s tomb was stripped of its gold and jewel ornamentation.[235] Adherents to Wahhabism, Saud’s followers, destroyed nearly every tomb dome in Medina in order to prevent their veneration,[235] and the one of Muhammad is reported to have narrowly escaped.[236] Similar events took place in 1925, when the Saudi militias retook—and this time managed to keep—the city.[237][238][239] In the Wahhabi interpretation of Islam, burial is to take place in unmarked graves.[236] Although the practice is frowned upon by the Saudis, many pilgrims continue to practice a ziyarat—a ritual visit—to the tomb.[240][241]

Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (“the Prophet’s mosque”) in Medina, Saudi Arabia, with the Green Dome built over Muhammad’s tomb in the center

After Muhammad

Muhammad united several of the tribes of Arabia into a single Arab Muslim religious polity in the last years of his life. With Muhammad’s death, disagreement broke out over who his successor would be.[12][13] Umar ibn al-Khattab, a prominent companion of Muhammad, nominated Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s friend and collaborator. With additional support Abu Bakr was confirmed as the first caliph. This choice was disputed by some of Muhammad’s companions, who held that Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, had been designated the successor by Muhammad at Ghadir Khumm. Abu Bakr immediately moved to strike against the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman Empire) forces because of the previous defeat, although he first had to put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in an event that Muslim historians later referred to as the Ridda wars, or “Wars of Apostasy”.[l]

The pre-Islamic Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sassanian empires. The Roman–Persian Wars between the two had devastated the region, making the empires unpopular amongst local tribes. Furthermore, in the lands that would be conquered by Muslims many Christians (Nestorians, Monophysites, Jacobites and Copts) were disaffected from the Eastern Orthodox Church which deemed them heretics. Within a decade Muslims conquered Mesopotamia, Byzantine Syria, Byzantine Egypt,[242] large parts of Persia, and established the Rashidun Caliphate.

According to William Montgomery Watt, religion for Muhammad was not a private and individual matter but “the total response of his personality to the total situation in which he found himself. He was responding [not only]… to the religious and intellectual aspects of the situation but also to the economic, social, and political pressures to which contemporary Mecca was subject.”[243] Bernard Lewis says there are two important political traditions in Islam—Muhammad as a statesman in Medina, and Muhammad as a rebel in Mecca. In his view, Islam is a great change, akin to a revolution, when introduced to new societies.[244]

Historians generally agree that Islamic social changes in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery and the rights of women and children improved on the status quo of Arab society.[244][m] For example, according to Lewis, Islam “from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents”.[which?][244] Muhammad’s message transformed society and moral orders of life in the Arabian Peninsula; society focused on the changes to perceived identity, world view, and the hierarchy of values.[245][page needed] Economic reforms addressed the plight of the poor, which was becoming an issue in pre-Islamic Mecca.[246] The Quran requires payment of an alms tax (zakat) for the benefit of the poor; as Muhammad’s power grew he demanded that tribes who wished to ally with him implement the zakat in particular.[247][248]

Appearance

According to the accounts of Anas and al-Bara in Sahih al-Bukhari, Muhammad had an average height, a robust frame, and broad shoulders. His complexion was neither completely white nor deep brown, and his hair was neither curly nor straight, reaching his earlobes. At the time of his death, he had a few white hairs in his head and beard.[249][250]

In Thirmidhi’s Shama’il al Mustafa, Ali and Hind ibn Abi Hala portrayed Muhammad as having a medium height, a white, round face, wide black eyes, and long eyelashes. His thick, curly hair reached beyond his earlobes, and he had a bright, luminous complexion. Additional features included a wide forehead, fine arched eyebrows, a vein between the eyebrows, a hooked nose, a thick beard, smooth cheeks, a strong mouth with teeth set apart, and a neck like an ivory statue. His build was well-proportioned, stout, and broad-chested, with a firm grip.[251][252][253]

The “seal of prophecy” between Muhammad’s shoulders is commonly described as a raised mole the size of a pigeon’s egg.[252] Another account of Muhammad’s appearance comes from Umm Ma’bad, a woman he met on his journey to Medina, who depicted him as a handsome and elegant figure with perfect posture. He has a clean and attractive face, with deep black eyes and thick eyelashes. His beard is dense, and his finely arched eyebrows are connected. When he is silent, he displays a calm and dignified demeanor, and when he speaks, an aura of majesty surrounds him. His voice is melodious and he has a long neck. His speech is captivating and eloquent, yet never frivolous, resembling a flowing string of pearls.[254][255]

Descriptions like these were often reproduced in calligraphic panels (Turkish: hilye), which in the 17th century developed into an art form of their own in the Ottoman Empire.[254]

Household

Muhammad’s life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca (from 570 to 622), and post-hijra in Medina (from 622 until 632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives in total (although two have ambiguous accounts, Rayhana bint Zayd and Maria al-Qibtiyya, as wife or concubine[n][256]). Eleven of the thirteen marriages occurred after the migration to Medina.

At the age of 25, Muhammad married the wealthy Khadijah bint Khuwaylid who was 40 years old.[257] The marriage lasted for 25 years and was a happy one.[258] Muhammad did not enter into marriage with another woman during this marriage.[259][260] After Khadijah’s death, Khawla bint Hakim suggested to Muhammad that he should marry Sawdah bint Zamah, a Muslim widow, or Aisha, daughter of Umm Ruman and Abu Bakr of Mecca. Muhammad is said to have asked for arrangements to marry both.[192]

According to traditional sources, Aisha was six or seven years old when betrothed to Muhammad,[192][261][262] with the marriage not being consummated until she reached the age of nine or ten years old.[o] She was therefore a virgin at marriage.[261] Modern Muslim authors who calculate Aisha’s age based on other sources of information, such as a hadith about the age difference between Aisha and her sister Asma, estimate that she was over thirteen and perhaps in her late teens at the time of her marriage.[p]

After migration to Medina, Muhammad, who was then in his fifties, married several more women.

Muhammad performed household chores such as preparing food, sewing clothes, and repairing shoes. He is also said to have had accustomed his wives to dialogue; he listened to their advice, and the wives debated and even argued with him.[274][275][276]

Khadijah is said to have had four daughters with Muhammad (Ruqayyah bint Muhammad, Umm Kulthum bint Muhammad, Zainab bint Muhammad, Fatimah Zahra) and two sons (Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad and Qasim ibn Muhammad, who both died in childhood). All but one of his daughters, Fatimah, died before him.[277] Some Shi’a scholars contend that Fatimah was Muhammad’s only daughter.[278] Maria al-Qibtiyya bore him a son named Ibrahim ibn Muhammad, but the child died when he was two years old.[277]

Nine of Muhammad’s wives survived him.[256] Aisha, who became known as Muhammad’s favourite wife in Sunni tradition, survived him by decades and was instrumental in helping assemble the scattered sayings of Muhammad that form the Hadith literature for the Sunni branch of Islam.[192]

Muhammad’s descendants through Fatimah are known as sharifs, syeds or sayyids. These are honorific titles in Arabic, sharif meaning ‘noble’ and sayed or sayyid meaning ‘lord’ or ‘sir’. As Muhammad’s only descendants, they are respected by both Sunni and Shi’a, though the Shi’a place much more emphasis and value on their distinction.[279]

Zayd ibn Haritha was a slave that Khadija gave to Muhammad. He was bought by her nephew Hakim bin Hizam at the market in Ukaz.[280] Zayd then became the couple’s adopted son, but was later disowned when Muhammad was about to marry Zayd’s ex-wife, Zaynab bint Jahsh.[281] According to a BBC summary, “the Prophet Muhammad did not try to abolish slavery, and bought, sold, captured, and owned slaves himself. But he insisted that slave owners treat their slaves well and stressed the virtue of freeing slaves. Muhammad treated slaves as human beings and clearly held some in the highest esteem”.[282]

Legacy

Islamic tradition

Following the attestation to the oneness of God, the belief in Muhammad’s prophethood is the main aspect of the Islamic faith. Every Muslim proclaims in Shahadah: “I testify that there is no god but God, and I testify that Muhammad is a Messenger of God”. The Shahadah is the basic creed or tenet of Islam. Islamic belief is that ideally the Shahadah is the first words a newborn will hear; children are taught it immediately and it will be recited upon death. Muslims repeat the shahadah in the call to prayer (adhan) and the prayer itself. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.[283]

In Islamic belief, Muhammad is regarded as the last prophet sent by God.[284][285] Qur’an 10:37 states that “…it (the Quran) is a confirmation of (revelations) that went before it, and a fuller explanation of the Book—wherein there is no doubt—from The Lord of the Worlds”. Similarly, 46:12 states “…And before this was the book of Moses, as a guide and a mercy. And this Book confirms (it)…”, while Quran 2:136 commands the believers of Islam to “Say: we believe in God and that which is revealed unto us, and that which was revealed unto Abraham and Ishmael and Isaac and Jacob and the tribes, and that which Moses and Jesus received, and which the prophets received from their Lord. We make no distinction between any of them, and unto Him we have surrendered.”

Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several miracles or supernatural events.[286] For example, many Muslim commentators and some Western scholars have interpreted the Surah 54:1–2 as referring to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh when they began persecuting his followers.[287][288] Western historian of Islam Denis Gril believes the Quran does not overtly describe Muhammad performing miracles, and the supreme miracle of Muhammad is identified with the Quran itself.[287]

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad was attacked by the people of Ta’if and was badly injured. The tradition also describes an angel appearing to him and offering retribution against the assailants. It is said that Muhammad rejected the offer and prayed for the guidance of the people of Ta’if.[289]

The Sunnah represents actions and sayings of Muhammad (preserved in reports known as Hadith) and covers a broad array of activities and beliefs ranging from religious rituals, personal hygiene, and burial of the dead to the mystical questions involving the love between humans and God. The Sunnah is considered a model of emulation for pious Muslims and has to a great degree influenced the Muslim culture. The greeting that Muhammad taught Muslims to offer each other, “may peace be upon you” (Arabic: as-salamu ‘alaykum) is used by Muslims throughout the world. Many details of major Islamic rituals such as daily prayers, the fasting and the annual pilgrimage are only found in the Sunnah and not the Quran.[291]

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad’s life, his intercession and of his miracles have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry. Among Arabic odes to Muhammad, Qasidat al-Burda (“Poem of the Mantle”) by the Egyptian Sufi al-Busiri (1211–1294) is particularly well-known, and widely held to possess a healing, spiritual power.[292] The Quran refers to Muhammad as “a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds”[293][11] The association of rain with mercy in Oriental countries has led to imagining Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessings and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth.[q][11] Muhammad’s birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Islamic world, excluding Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged.[294] When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad, they usually follow it with the Arabic phrase ṣallā llahu ʿalayhi wa-sallam (may God honor him and grant him peace) or the English phrase peace be upon him.[295] In casual writing, the abbreviations SAW (for the Arabic phrase) or PBUH (for the English phrase) are sometimes used; in printed matter, a small calligraphic rendition is commonly used (ﷺ).

Sufism

The Sunnah contributed much to the development of Islamic law, particularly from the end of the first Islamic century.[296] Muslim mystics, known as sufis, who were seeking for the inner meaning of the Quran and the inner nature of Muhammad, viewed the prophet of Islam not only as a prophet but also as a perfect human being. All Sufi orders trace their chain of spiritual descent back to Muhammad.[297]

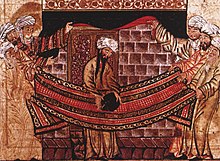

Depictions

In line with the hadith’s prohibition against creating images of sentient living beings, which is particularly strictly observed with respect to God and Muhammad, Islamic religious art is focused on the word.[298][299] Muslims generally avoid depictions of Muhammad, and mosques are decorated with calligraphy and Quranic inscriptions or geometrical designs, not images or sculptures.[298][300] Today, the interdiction against images of Muhammad—designed to prevent worship of Muhammad, rather than God—is much more strictly observed in Sunni Islam (85%–90% of Muslims) and Ahmadiyya Islam (1%) than among Shias (10%–15%).[301] While both Sunnis and Shias have created images of Muhammad in the past,[302] Islamic depictions of Muhammad are rare.[298] They have mostly been limited to the private and elite medium of the miniature, and since about 1500 most depictions show Muhammad with his face veiled, or symbolically represent him as a flame.[300][303]

The earliest extant depictions come from 13th century Anatolian Seljuk and Ilkhanid Persian miniatures, typically in literary genres describing the life and deeds of Muhammad.[303][304] During the Ilkhanid period, when Persia’s Mongol rulers converted to Islam, competing Sunni and Shi’a groups used visual imagery, including images of Muhammad, to promote their particular interpretation of Islam’s key events.[305] Influenced by the Buddhist tradition of representational religious art predating the Mongol elite’s conversion, this innovation was unprecedented in the Islamic world, and accompanied by a “broader shift in Islamic artistic culture away from abstraction toward representation” in “mosques, on tapestries, silks, ceramics, and in glass and metalwork” besides books.[306] In the Persian lands, this tradition of realistic depictions lasted through the Timurid dynasty until the Safavids took power in the early 16th century.[305] The Safavaids, who made Shi’i Islam the state religion, initiated a departure from the traditional Ilkhanid and Timurid artistic style by covering Muhammad’s face with a veil to obscure his features and at the same time represent his luminous essence.[307] Concomitantly, some of the unveiled images from earlier periods were defaced.[305][308][309] Later images were produced in Ottoman Turkey and elsewhere, but mosques were never decorated with images of Muhammad.[302] Illustrated accounts of the night journey (mi’raj) were particularly popular from the Ilkhanid period through the Safavid era.[310] During the 19th century, Iran saw a boom of printed and illustrated mi’raj books, with Muhammad’s face veiled, aimed in particular at illiterates and children in the manner of graphic novels. Reproduced through lithography, these were essentially “printed manuscripts”.[310] Today, millions of historical reproductions and modern images are available in some Muslim-majority countries, especially Turkey and Iran, on posters, postcards, and even in coffee-table books, but are unknown in most other parts of the Islamic world, and when encountered by Muslims from other countries, they can cause considerable consternation and offense.[302][303]

European appreciation

After the Reformation, Muhammad was often portrayed in a similar way.[11][311] Guillaume Postel was among the first to present a more positive view of Muhammad when he argued that Muhammad should be esteemed by Christians as a valid prophet.[11][312] Gottfried Leibniz praised Muhammad because “he did not deviate from the natural religion”.[11] Henri de Boulainvilliers, in his Vie de Mahomed which was published posthumously in 1730, described Muhammad as a gifted political leader and a just lawmaker.[11] He presents him as a divinely inspired messenger whom God employed to confound the bickering Oriental Christians, to liberate the Orient from the despotic rule of the Romans and Persians, and to spread the knowledge of the unity of God from India to Spain.[313] Voltaire had a somewhat mixed opinion on Muhammad: in his play Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophète he vilifies Muhammad as a symbol of fanaticism, and in a published essay in 1748 he calls him “a sublime and hearty charlatan”, but in his historical survey Essai sur les mœurs, he presents him as legislator and a conqueror and calls him an “enthusiast”.[313] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Social Contract (1762), “brushing aside hostile legends of Muhammad as a trickster and impostor, presents him as a sage legislator who wisely fused religious and political powers”.[313] Emmanuel Pastoret published in 1787 his Zoroaster, Confucius and Muhammad, in which he presents the lives of these three “great men”, “the greatest legislators of the universe”, and compares their careers as religious reformers and lawgivers. He rejects the common view that Muhammad is an impostor and argues that the Quran proffers “the most sublime truths of cult and morals”; it defines the unity of God with an “admirable concision”. Pastoret writes that the common accusations of his immorality are unfounded: on the contrary, his law enjoins sobriety, generosity, and compassion on his followers: the “legislator of Arabia” was “a great man”.[313] Napoleon Bonaparte admired Muhammad and Islam,[314] and described him as a model lawmaker and a great man.[315][316] Thomas Carlyle in his book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History (1841) describes “Mahomet” as “A silent great soul; he was one of those who cannot but be in earnest”.[317] Carlyle’s interpretation has been widely cited by Muslim scholars as a demonstration that Western scholarship validates Muhammad’s status as a great man in history.[318]

Ian Almond says that German Romantic writers generally held positive views of Muhammad: “Goethe’s ‘extraordinary’ poet-prophet, Herder’s nation builder (…) Schlegel’s admiration for Islam as an aesthetic product, enviably authentic, radiantly holistic, played such a central role in his view of Mohammed as an exemplary world-fashioner that he even used it as a scale of judgement for the classical (the dithyramb, we are told, has to radiate pure beauty if it is to resemble ‘a Koran of poetry’)”.[319] After quoting Heinrich Heine, who said in a letter to some friend that “I must admit that you, great prophet of Mecca, are the greatest poet and that your Quran… will not easily escape my memory”, John Tolan goes on to show how Jews in Europe in particular held more nuanced views about Muhammad and Islam, being an ethnoreligious minority feeling discriminated, they specifically lauded Al-Andalus, and thus, “writing about Islam was for Jews a way of indulging in a fantasy world, far from the persecution and pogroms of nineteenth-century Europe, where Jews could live in harmony with their non-Jewish neighbors”.[320]

Recent writers such as William Montgomery Watt and Richard Bell dismiss the idea that Muhammad deliberately deceived his followers, arguing that Muhammad “was absolutely sincere and acted in complete good faith”[321] and Muhammad’s readiness to endure hardship for his cause, with what seemed to be no rational basis for hope, shows his sincerity.[322] Watt, however, says that sincerity does not directly imply correctness: in contemporary terms, Muhammad might have mistaken his subconscious for divine revelation.[323] Watt and Bernard Lewis argue that viewing Muhammad as a self-seeking impostor makes it impossible to understand Islam’s development.[324][325] Alford T. Welch holds that Muhammad was able to be so influential and successful because of his firm belief in his vocation.[11]

Other religions

Followers of the Baháʼí Faith venerate Muhammad as one of a number of prophets or “Manifestations of God”. He is thought to be the final manifestation, or seal of the Adamic cycle, but consider his teachings to have been superseded by those of Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí faith, and the first manifestation of the current cycle.[326][327]

Druze tradition honors several “mentors” and “prophets”,[328] and Muhammad is considered an important prophet of God in the Druze faith, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[329][330]

Criticism