We have a good deal of research on the transition of the corporation from the functional to the Divisionalized Form, much of it from the Harvard Business School, which has shown a special interest in the structure of the large corporation. Figure 11-3 and the discussion that follows borrow from these results to describe four stages of that transition.

We begin with the large corporation that produces all its products through one chain and so retains what we call the integrated form—a pure functional structure, a Machine Bureaucracy or perhaps an Adhocracy. As the corporation begins to market somie of the intermediate products of its production processes, it makes the first shift toward divisionalization, called the by-product form. Further moves in the same direction, to the point where the by-products become more important than end products although a central theme remains in the product-market strategy, lead to a structure closer to the divisionalized one, which is called the related- product form. And finally, the complete breakdown of the production chain, to the point where the different products have no relationship with each other, takes the corporation to the conglomerate form, a pure divi- sional structure. Although some corporations may move through all these stages in sequence, we shall see that others stop at one stage along the way because of very high fixed-cost technical systems (typical in the case of the integrated form), operations based on a single raw material (typical in the case of the by-product form), or focus on a core technology or market theme (typical in the case of the related-product form).

1. The integrated form

At the top of Figure 11-3 is the pure functional form, used by the corpora- tion whose production activities form one integrated, unbroken chain. Only the final output is sold to the customers. The tight interdependences of the different activities make it impossible for such corporations to use the Divisionalized Form—that is, to grant autonomy to units performing any of the steps in the chain—and so they organize themselves as func-tional Machine Bureaucracies (or Adhocracies, if they face complex, dy- namic environments). They typically product a single product line, or at least one line dominates. Large firms using this structure also tend to be vertically integrated and capital-intensive. Units responsible for different steps in the production chain are sometimes called “divisions,” but since they have no choice but to buy from or sell to their sister units in the same corporation, they are essentially functional departments—means to the ultimate ends, or markets—and lack the autonomy of true divisions.

Figure 11 -3. Stages in the transition to the Divisionalized Form

Ironically, despite its reputation as the very model of divisionaliza- tion, General Motors seems to fit best into this category. That is, aside from its nonautomotive activities, which are relatively small (under 10 percent of total sales), the corporation seems not to be truly divisionalized at all, despite its use of that term. Earlier we saw that Sloan consolidated the structure of General Motors in the 1920s, converted a holding company into a divisionalized one. In fact, he continued to consolidate it throughout his tenure as chief executive officer, as, apparently, did his successors right up to the present time. Thus, one study of General Motors (Wrigley, 1970) describes its automobile production process as one integrated “closed sys- tem,” with neither the assembly operation nor Fisher Body permitted to sell its services to the open market, nor the automotive “divisions” (Chevrolet, Buick, and so on) to buy the services they need from that market. Central control of research, styling, engineering, plant construc- tion, production scheduling, quality control, pricing, and labor and dealer relations renders the structure a virtual functional one, with the divisions in some ways resembling marketing departments (with circumscribed powers even over that function).

2. The by-product form

As the integrated firm seeks wider markets, it may choose to diversify its end-product lines and shift all the way over to the pure divisional struc- ture. A less risky alternative, however, is to start by marketing its inter- mediate products on the open market. This introduces small breaks in its processing chain, which in turn call for a measure of divisionalization in its structure, what can be called the by-product form. Each link in the process- ing chain can now be given some autonomy in order to market its by- products, although it is understood that most of its outputs will be passed on internally to the next link in the chain. But because the processing chain remains more or less intact, headquarters retains considerable control over strategy formulation and some aspects of operations as well. Specifically, it relies on action planning to manage the interdependences between the divisions.

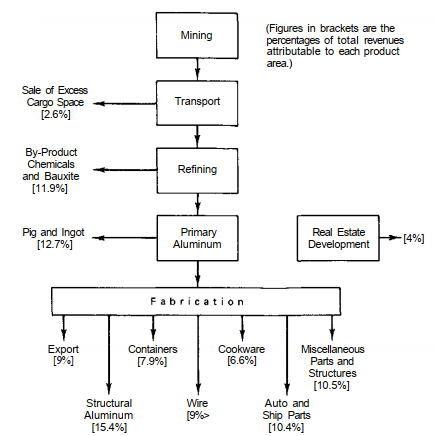

Many of the organizations that fall into this category are vertically integrated ones that base their operations on a single basic material, such as wood, oil, or aluminum, which they process to a variety of consumable end products. Figure 11-4 shows the 1969 processing chain for Alcoa, which earned 69 percent of its revenue from fabricated aluminum end products, such as cookware and auto parts, and 27 percent from intermedi- ate by-products, including cargo space, chemicals, bauxite, and pit and ingot aluminum. (Real estate development—a horizontally diversified ser- vice—accounted for the remaining 4 percent.)

3. The related-product form

Some corporations continue to diversify their by-product markets, further breaking down their processing chain until what the divisions sell on the open market becomes more important than what they supply to each other. The organization then moves to the related-product form. For exam-ple, a firm manufacturing washing machines may set up a division to produce the motors. Eventually, the motor division may become so suc- cessful on its own that the washing-machine division is no longer its domi- nant customer. A more serious form of divisionalization is then called for, to reflect the greater independence of the divisions.

Figure 11-4. By-product and end-product sales of Alcoa in 1969 (from Rumelt, 1974:21; prepared from data in com- pany’s annual reports)

What typically holds the divisions of these firms together is some common thread among their products, sometimes a core skill or technol- ogy, sometimes a central market theme. The divisions often sell to many of the same outside customers as well. In effect, the firm retains a semblance of an integrated product-market strategy.

Central planning at the headquarters in the related-product form must be less constraining than in the by-product form, more concerned with measuring performance than prescribing actions. A good deal of the control over the specific product-market strategies must revert to the divi-sions. But the interdependencies around the central product-market theme encourage the headquarters to retain functions common to the divisions— for example, research and development in the case of a core technology. These central functions are, of course, the “critical” ones for the corpora- tion, so the functional/divisional hybrids—specifically, the ones with prod- uct or service divisions, such as insurance companies that centralize the critical function of investment—would fall into this grouping.

So too might a firm such as General Electric, whose organigram (circa 1975) is shown in Figure 11-5. As Wrigley described the firm in 1970, some products, such as artificial diamonds, were sold mainly to outside users, whereas others, such as small motors, were supplied both to inside and outside users. The structure was divisionalized—in fact, as can be seen, multiple-divisionalized—in a typical way, except that there were a greater number of support services at headquarters than we described earlier for the basic structure. Wrigley noted that these included labor relations (with line responsibility for major negotiations), market forecasting, engineer- ing, and marketing (the last two providing consulting services), as well as the “spearhead” of the firm’s massive research and development effort— one of its critical functions. He also noted that the division managers were given little control over management development or suppliers, two other functions apparently viewed as critical. Otherwise they had considerable freedom to run their own businesses and formulate their product-market strategies.

4. The conglomerate form

As the related-product firm expands into new markets or acquires other firms, with less and less regard for a central strategic theme, the organiza- tion moves to the conglomerate form and adopts a pure divisionalized struc- ture, the one we described earlier in this chapter as the basic structure. Each division serves its own markets, producing product lines unrelated to those of the other divisions—thumbtacks in one, steam shovels in a sec- ond, funeral services in a third. In the conglomerate, there are no impor- tant interdependences among the divisions, save for the pooling of re- sources. As a result, the headquarters planning and control system becomes simply a vehicle for regulating performance, specifically financial performance. And the headquarters staff diminishes to almost nothing—a few general or group managers supported by some financial analysts and a minimum of other services. As a chief executive of Textron commented— where a central staff of thirty oversaw thirty divisions doing more than $1.5 billion of sales volume:

A key concept is that we have a minimum of home staff. It consists almost entirely of line managers and clerical personnel, with virtually no staff help- ing the line managers. We have no R and D section or manufacturing section or marketing section, for example. With our collection of businesses, what would they do? Neither do we have any corporate labour relations officer or staff. We want the unions to bargain separately in each of our divisions, and we will not send any corporate representatives to any labour negotiations. (quoted in Wrigley, 1970:V-76-77)

One thing that can, however, vary widely in the conglomerate form is the tightness of the performance control system, although it always re- mains financial. At one extreme is the highly managed system of ITT, which became increasingly fashionable in the 1970s, with tenth-of-the- month “flash” reports and the like. At the other extreme, although far less fashionable, is the holding company, a federation of businesses so loose that it is probably not even appropriate to think of it as one entity. The holding company typically has no central headquarters and no real control system, save for the occasional meeting of its different presidents. This is the logical finale to our discussion of the stages in the transition to the Divisionalized Form—fragmentation of structure to the point where we can no longer talk of a single organization.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.