Whether the proposed approach leads to a better understanding of or to implications different from those found in received microtheory can best be established by addressing it to particular economic phenomena. Three are examined here: price discrimination, the insurance problem, and Stigler’s life cycle treatment of vertical integration. Although the first of these does not ordinarily entail market and hierarchy choices, price discrimination has the advantage of being familiar and does raise transaction cost issues. Except to the extent that self-insurance is a viable alternative, neither does the insurance problem expressly pose market and hierarchy issues. It is, however, a paradigmatic problem, the attributes of which will recur in a variety of contracting contexts in the chapters that follow. Stigler’s treatment of vertical integration is directly concerned with market and hierarchy issues.

1. Price Discrimination

The differences between received microtheory and the transaction cost approach can be illustrated by examining the familiar problem of price discrimination. As will be evident, the transaction cost approach does not abandon but rather augments the received microtheory model.

Assume that the market in question is one for which economies of scale are large in relation to the size of the market, in which case the average cost curve falls over a considerable output range. Assume, in particular, that demand and cost conditions are as shown in Figure 1. The unregulated monopolist who both maximizes profits and sells his output at a single, uniform price to all customers will restrict output below the social optimum (shown by Q* in Figure 1), at which marginal cost equals price.1 Instead, the monopolist will restrict his output to Qm, where marginal cost equals marginal revenue and an excess of price over marginal cost obtains.

It is sometimes argued, however, that price discrimination will correct the allocative efficiency distortion referred to. In particular, the monopolist who segregates his market in such a way that each customer is made to pay his full valuation (given by the demand curve) for each unit of output has the incentive to add successive units of output until the price paid for the last item sold just equals the marginal cost. The fully discriminating monopolist will thus be led to expand output from Qm to Q*. Although income distribution will be affected in the process (in possibly objectionable ways), the output distortion noted earlier is removed and an allocative efficiency gain is realized.

Evaluating this allocative efficiency claim gives us our first opportunity to contrast the conventional analysis of received microtheory with a transactions cost approach. Implicit in the above conventional microtheory argument is an assumption that the costs of both discovering true customer valuations for the product and enforcing restrictions against resale ( so that there can be no arbitrage) are negligible and can be disregarded. Such costs vanish, however, only if either (1) customers will honestly self-reveal preferences and self-enforce nonresale promises (no opportunism); or (2) the seller is omniscient, a possibility that requires unbounded rationality of an especially strong kind. Inasmuch as assumptions of both kinds are plainly unrealistic, the question naturally arises: Does an allocative efficiency gain obtain when nontrivial transaction costs must be incurred to discover true customer valuations and/or to police nonresale restrictions? Unfortunately for received microtheory, the outcome is uncertain if these transaction costs are introduced.

Figure 1.

To see this, assume (for simplicity) that the transaction costs of accom- plishing full price discrimination are independent of the level of output: The costs are either zero, in which event no effort to price discriminate is made, or T, in which case customer valuations become fully known and enforcement against cheating is complete? Price discrimination will of course be attractive to the monopolist if a net profit gain can be shown — a situation that will obtain if the additional revenues (which are given by the two shaded regions, A1 and A2, in Figure 1) exceed the costs of achieving discrimination, T. Interesting for social welfare evaluation purposes is the fact that an incremental gross welfare gain is realized only on output that exceeds Qm. This gain is given by the lower triangle (A2). Consequently, the net social welfare effects will be positive only if A2 exceeds the transaction costs, T. An allocative efficiency loss, occasioned by high transaction costs, but a private monopoly gain, derived from price discrimination applied to all output, is therefore consistent with fully discriminatory pricing in circumstances where nontrivial transaction costs are incurred in reaching the discriminatory result. More precisely, if T is less than A1 plus A2 but more than A2 alone, the monopolist will be prepared to incur the customer information and policing costs necessary to achieve the discriminatory outcome, because his profits will be augmented (A1 + A2>T), but these same’expenditures will give rise to a net social welfare loss (A2<T).

Of course, in circumstances in which T is zero or negligible, this con- tradiction does not arise. Such may obtain if the product or service is costly to store (for example, electricity supply, telephone service), in which case arbitrage is made difficult and, whatever the opportunistic inclinations of buyers may be, promises not to resell become unimportant. The problem of discovering true valuations still remains, but this can often be approximated if customer classes can be segregated and low-cost metering devices are employed. I nevertheless emphasize that the conventional welfare gain associated with price discrimination rests crucially on the assumption that transaction costs of both valuation and policing kinds are negligible. If these cannot be so characterized, such transaction costs need expressly to be taken into account before a welfare assessment is ventured.

2. The Insurance Example

As indicated, the insurance example is interesting not merely for its own sake but also because the parameters of the insurance problem can be reinterpreted in such a way as to expose the problems that employment contracts, vertical integration, and competition in the capital market confront. It is also interesting because it poses what may be referred to as the “information impactedness” problem. (Information impactedness is a derivative condition in the organizational failures framework. It is mainly attributable to the pairing of uncertainty with opportunism. It exists in circumstances in which one of the parties to an exchange is much better informed than is the other regarding underlying conditions germane to the trade, and the second party cannot achieve information parity except at great cost —because he cannot rely on the first party to disclose the information in a fully candid manner.7)

Risk aversion will be assumed and the question is whether a group of individuals who are exposed to independent risks will be able to pool these successfully with an insurer. Assume further that the members of the group are uniformly distributed over the risk interval p1 to p2, where p1 < p2, and p denotes the probability for a particular individual that the contingency to be insured will eventuate. (Because this probability will vary depending on the risk-mitigating actions taken by an individual, assume that p reflects efficient risk mitigation. ) Whereas individuals will be assumed to know their risk characteristics exactly, the insurer is unable, at low cost, to distinguish one member of the group from another. Information impactedness thus obtains. Assume also that the highest premium that an individual of risk classp will pay is (p + ∈)D, where ∈ < (p2—p1)/2, and D is the (common) damage that will be incurred if the contingency obtains.

In the absence of other information, and assuming transactions costs to be negligible, insurers would break even if they could sell insurance to all members of this group at a premium of [ (p1 + p2 )/2 ] D, which is the mean loss. Such a premium will regarded as excessive, however, by those good- risk types for whom p + ∈<C{p1+p2)/2. Inasmuch as these preferred risks cannot easily establish that they are honestly entitled to a lower premium — because ( opportunistic ) poor-risk types can make the same representations and insurers are unable ( except at great cost) to distinguish between them —they will withdraw. Breakeven then requires that remaining parties be charged a higher premium; the system will stabilize eventually at a premium of (p2 — ∈)D. Information impactedness and opportunism thus result in what is commonly referred to as the “adverse selection” problem.

Moreover, the matter does not end here if the extent of the losses incurred is influenced by the degree to which insured parties take steps designed to mitigate losses. If promises were self-enforcing, insurers need merely extract a promise from insureds that, once insured, they will behave “re-sponsibly. Alternatively, if it could easily be discerned ex post whether efficient contingency-mitigating practices had or had not been followed, insurers could supply insureds with appropriate incentives to behave re- sponsibly by paying only those claims that fell within the terms of the agree- ment. If, however, such determinations can be made only at great cost and (some) insureds exploit ex post information differentials opportunistically, the problem referred to in the insurance literature as “moral hazard” (Arrow, 1971, pp. 142, 202, 243) obtains. Premiums will be increased on this account as well. Note also that responsible parties who would otherwise be prepared to self-enforce promises to take efficient loss-mitigating actions may find that such behavior is not competitively viable and will consequently be induced to imitate opportunistic types by underinvesting in loss mitigation.4 A sort of Gresham’s Law of Behavior obtains.

Revising the terms of a contract to reflect the additional information gleaned from experience may be referred to as experience rating. The prospect that this will be done serves to curb opportunism in contract execution. Inferior agents will nevertheless be able to exploit information impactedness, however, unless original terms are relatively severe (that is, no bargains are to be had on joining) or parties are unable easily to opt out when terms are adjusted adversely against them.

One way to accomplish the latter is that markets pool their experience so that opportunistic types cannot secure better terms by “quitting” and turning elsewhere. This pooling requires that a common language be devised for describing agent characteristics, which will be greatly facilitated if the behavior in question can be easily quantified. If, instead, the judgments to be made are highly subjective, the costs of communication needed to support a collective experience rating system are apt to be prohibitive in relation to the gains — if the organizational mode is held constant.5

Experience-rating is also of interest to superior risk/responsible types. Good risks and/or those who would be prepared to self-enforce promises to mitigate losses efficiently may be induced to join at a high premium by the assurance that premiums will subsequently be made on a more dis- criminating basis as information accumulates. This offer will be especially attractive if, rather than merely revise a priori probabilities on the basis of claim experience, performance audits are also made — because, without a performance audit, the true explanation for outcomes that are jointly de- pendent on the state of nature that obtains and the behavior of the economic agent cannot be accurately established (Arrow, 1969, p. 55). Monitoring thus helps restore markets that are otherwise beset with opportunistic distortions to more efficient configurations — albeit that some degree of imperfection, in a net benefit sense, is irremediable (the costs of complete information parity are simply prohibitive).

3. Stigler on Vertical Integration

Stigler’s explication, as it applies to vertical integration, of Adam Smith s theorem that “the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market” leads to his deduction of the following life cycle implications: Vertical integration will be extensive in firms in young industries: disintegration will be observed as an industry grows; and reintegration will occur as an industry passes into decline (1968, pp. 129-141). These life cycle effects are illustrated by reference to a multiprocess product, each of which processes involves a separable technology and hence has its own distinct cost function.10 Some of the processes display individually falling cost curves, others rise continuously, and still others have U-shaped cost curves.

Stigler then inquires: Why does not the firm exploit the decreasing cost activities by expanding them to become a monopoly? He answers by observing that, at the outset, the decreasing cost functions may be “too small to support a specialized firm or firms” (1968, p. 133). But, unless the argument is meant to be restricted to global or local monopolies, for which there is no indication, resort to a specialized firm does not exhaust the possibilities. Assuming that there are at least several rival firms in the business, why does not one of these exploit the available economies, to the mutual benefit of all the parties, by producing the entire requirement for the group? The reasons, I submit, turn on transaction cost considerations.

If, for example, the exchange of specialized information between the parties is involved (Stigler specifically refers to “market information” as one of the decreasing cost possibilities), strategic misrepresentation issues are posed. The risk here is that the specialist firm will disclose information to its rivals in an incomplete and distorted manner. Because the party buying the information can establish its accuracy only at great cost, possibly only by collecting the original data itself, the exchange fails to go through. If, however, rivals were not given to being opportunistic, the risk of strategic distortion would vanish and the (organizationally efficient) specialization of information could proceed.

The exchange of physical components that experience decreasing costs is likewise discouraged where both long-term and spot market contracts prospectively incur transactional difficulties. Long-term contracts are principally impeded by bounded rationality considerations: Given bounded rationality, the extent to which uncertain future events can be expressly taken into account — in the sense that appropriate adaptations thereto are costed out and contractually specified — is simply limited. Because, given opportunism, incomplete long-term contracts predictably pose interest conflicts between the parties, other arrangements are apt to be sought.

Spot market (short-term) contracting is an obvious alternative. Such contracts, however, are hazardous if a small-numbers supply relation obtains—a condition that, by assumption, holds for the circumstances described by Stigler. The buyer then incurs the risk that the purchased product or service will, at some time, be supplied under monopolistic terms. Industry growth, moreover, need not eliminate the tension of small-numbers bargaining if the item in question is one for which learning by doing is important and if the market for human capital is imperfect.11 Delaying own-production until own- requirements are sufficient to exhaust scale economies would, considering the learning costs of undertaking own- production at this later time, incur substantial transition costs. It may, under these conditions, be more attractive from the outset for each firm to produce its own requirements — or, alternatively, for the affected firms to merge.6 7 Without present or prospective transaction costs of the sorts described, however, specialization by one of the firms (that is, monopoly supply), to the mutual benefit of all, would presumably occur. Put differently, technology is no bar to contracting; it is transactional considerations that are decisive.

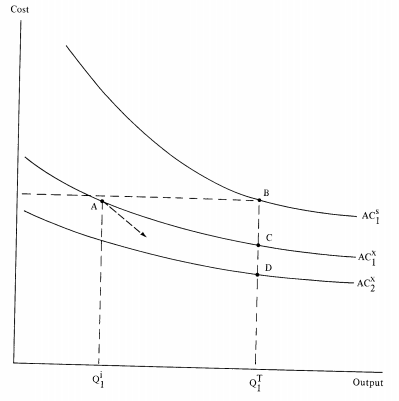

Aspects of the above argument can be illustrated with the help of Figure 2. The average costs of supplying the item in question by a specialized outside supplier at time 1 are shown by the curve ![]() . Firms that are already in the industry can supply the same item at the average costs shown by

. Firms that are already in the industry can supply the same item at the average costs shown by ![]() The curve

The curve ![]() is everywhere above the curve

is everywhere above the curve ![]() because firms already in the industry avoid the setup costs that a specialized outside supplier would incur. Each of the firms in the industry generates requirements for the item at time 1 of

because firms already in the industry avoid the setup costs that a specialized outside supplier would incur. Each of the firms in the industry generates requirements for the item at time 1 of ![]() The total industry requirements at time 1 is

The total industry requirements at time 1 is ![]() .

.

Figure 2.

The implicit comparison that Stigler makes in his explanation for vertical integration is point A versus point B. Thus, although having a specialized supplier service the whole industry (produce ![]() ) would permit economies of scale to be more fully exploited, the declining cost advantage is more than offset by the setup costs – on which account the average costs of the specialized supplier (at B) exceed the average costs that each individual firm would incur by supplying its own requirements (at /1). My argument, however, is that point

) would permit economies of scale to be more fully exploited, the declining cost advantage is more than offset by the setup costs – on which account the average costs of the specialized supplier (at B) exceed the average costs that each individual firm would incur by supplying its own requirements (at /1). My argument, however, is that point

/1 should also be compared with point C- w ere point C shows the average costs of supplying the requirements for e entire industry by one of the firms that is already in the industry. Such a firm does not incur those setup costs which disadvantage the outside specialist supplier. Given the decreasing cost technology that Stigler assumes, the average costs at C are necessarily less than those at A. Why then not have one of the firms already in the industry supply both itself and all others? The impediments, I submit, are the above described hazards o interfirm contracting (of both long-term and spot market types), which is to say, transaction cost considerations, not technology, explain the outcome.

The comparison, moreover, can be extended to include a consideration of the curve ![]() which represents the average costs that will be incurred by an integrated firm at time 2 which has been supplying the product or service continuously during the interval from time 1 to time 2. The curve

which represents the average costs that will be incurred by an integrated firm at time 2 which has been supplying the product or service continuously during the interval from time 1 to time 2. The curve ![]() is everywhere lower than

is everywhere lower than ![]() by reason of learning-by-doing advantages. To the extent that such learning advantages are firm-specific, they will accrue only to firms that have undertaken own-production during the supply interval in question. Thus, if one of the firms in the industry becomes the monopoly supplier to all others at time 1 and if at time 2 the other firms become dissatisfied with the monopoly supplier’s terms, these buying firms cannot undertake own-supply at a later date on cost parity terms —because they have not had the benefit of learning-by-doing.

by reason of learning-by-doing advantages. To the extent that such learning advantages are firm-specific, they will accrue only to firms that have undertaken own-production during the supply interval in question. Thus, if one of the firms in the industry becomes the monopoly supplier to all others at time 1 and if at time 2 the other firms become dissatisfied with the monopoly supplier’s terms, these buying firms cannot undertake own-supply at a later date on cost parity terms —because they have not had the benefit of learning-by-doing.

Note finally the arrow that points away from point A toward point D. If the industry is expected to grow, which plainly is the case for the circum- stances described by Stigler, and if each of the firms in the industry can be expected to grow with it, then each firm, if it supplies its own requirements (![]() ) at time 1 and incurs average costs of A . can, by reason of both growth and learning-by-doing, anticipate declining own-supply costs — perhaps to the extent that each substantially exhausts the economies of scale that are available. Because own-supply avoids the transactional hazards of small- numbers outside procurement, vertical integration of the decreasing cost technology items to which Stigler refers is thus all the more to be expected.

) at time 1 and incurs average costs of A . can, by reason of both growth and learning-by-doing, anticipate declining own-supply costs — perhaps to the extent that each substantially exhausts the economies of scale that are available. Because own-supply avoids the transactional hazards of small- numbers outside procurement, vertical integration of the decreasing cost technology items to which Stigler refers is thus all the more to be expected.

Source: Williamson Oliver E. (1975), Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications, A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization, The Free Press.