The experience of the first large integrated enterprises in the meatpacking industries differed from that of the American Tobacco Company in two significant ways. First, because the packers’ products were perishable, the flow from the purchasing of the cattle to the sale to the consumer had to be even more carefully coordinated and controlled. With the refrigeration techniques of the day, beef was chilled, not frozen, and had to be consumed within three to four weeks of its butchering. This need led to an even heavier investment in capital equipment, particularly storage and transportation facilities, and required an even larger managerial organization than did the maintenance of high-volume flows in cigarettes and other packaged products.

Second, in meat packing, several large integrated organizations were formed almost simultaneously. One enterprise did not become a leader before the others. So the industry became oligopolistic rather than mo- nopolistic. In the dozen or so years after 1881, when Swift began to build a national branch-house distributing network, six integrated packers dominated the trade—two giants, Armour and Swift, and four smaller firms, Hammond, Morris, Cudahy, and Schwartzchild & Sulzberger.24 The first four all had their central offices in Chicago and had completed their network of branch houses, refrigerator cars, packing plants, and buying units by the mid-i88os. The Cudahy Brothers, former Armour associates, began in 1887 a new enterprise based in Omaha; in the early 1890s Schwartzchild & Sulzberger, a New York firm in the kosher trade, decided to have its own supplies and purchased a packing plant in Kansas City. It then built a national network of branch houses and obtained a fleet of refrigerated cars. By the early twentieth century these six firms (Hammond had become the nucleus of the National Packing Company) provided from 60 to over 90 percent of the dressed meat sold in the large eastern cities and 95 percent of American beef exports. They also handled a large share of the nation’s pork, lamb, and other animal products.25

The capitalization of “the Big Six” indicates their comparative size. Swift, the largest at the beginning of the century, had a stock issue of $35.0 million; Armour followed with $27.5 million; National (a combination in 1903 of Hammond and several small local firms) had $15.0 million; Cudahy $7.0; Morris $6.0; and Schwartzchild & Sulzberger $5.0 million.26 By 1903 Armour was slaughtering 7.3 million animals a year, and Swift 8.0 million.27 By 1917 Armour had surpassed Swift in volume and assets.

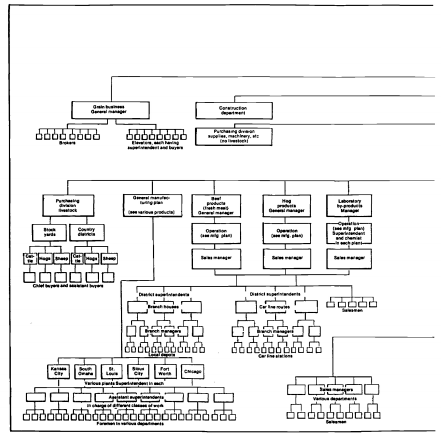

All these companies were directed through large, centralized, function- ally departmentalized offices. Swift’s Chicago headquarters employed a clerical force of over a thousand.28 Armour’s was much the same size. The organization chart of Armour & Company (figure 8) illustrates the size, complexity, and sophistication of the managerial hierarchy operating that vast integrated enterprise.29 The chart is for 1907, but Armour’s or- ganization had changed little during the previous ten to twelve years.

At Armour the manufacturing departments employed more men and managers than did those at American Tobacco and other producers of packaged goods. In meat packing the technology was less mechanized than in processing other products of the farm. The high volume of flow generated by the organization of a national sales and distribution network led to highly specialized subdivision of labor in the processes of slaughter- ing and dressing. As the Bureau of Corporations explained after a detailed investigation in 1904, the disassembling of a single steer involved 157 men who killed, dismembered, stored, and loaded the meat and whose work was divided into no less than seventy-eight distinct processes.30 This extreme subdivision of labor appeared only after a carefully designed administrative arrangement permitted an unprecedented high and steady movement of cattle through the packing plants. Without the replacement of market coordination by administrative coordination there would have been far less subdivision of labor in the meat packing trades.

The plant superintendents of Armour’s six great packing plants—at Chicago, St. Louis, Omaha, Kansas City, Sioux City, and Fort Worth— sent daily reports of the slaughtering completed for that day and that planned for the next. They worked closely with the managers from the purchasing division, the sales departments, the transportation department, and the by- products departments, in order to maintain a steady flow of meat through the enterprise.31 On the basis of orders received from the branch houses, the plant superintendent contacted the purchasing managers in his area. These included the manager in charge of local stockyard buying and the district manager in charge of buying cattle, hogs, and sheep directly from farmers. Normally the neighboring stockyard supplied close to 90 percent of the plant superintendent’s needs. Each of the purchasing executives had assistant managers for buying the three different types of animals—cattle, sheep, and pigs. As in the case of American Tobacco, Armour also had housed at its central office a purchasing division that bought in volume and at discount a wide variety of supplies used by all departments within the company.

Again, as in the case of American Tobacco Company, the sales organi- zation was the largest (in terms of the numbers of managers) of the func- tional departments. It was organized into two large subunits and a small one. One of the large departments distributed beef and the other hog products. Each also handled “offal” (liver, hearts, tongue, brains, and the like). At Armour, the third and much smaller sales organization distributed what were known as “laboratory by-products,” such as pepsin, elixer of enzymes, pancreatin, and extract of red-bone marrow.

All three divisions marketed their products through Armour’s nation- wide branch house organization, which by 1900 numbered 200 houses. At that time Swift was operating 193, Morris 77, Cudahy 57, and Schwartz- child & Sulzberger 44 comparable units.32 The branch houses, in addition to receiving and storing fresh meat and distributing it to local butchers and other retailers, took orders and arranged for local advertising. Its accountants handled billing and the transfer of funds back to Chicago. Armour and other packers supplemented their branch house networks with “peddler car routes,” or “car lines” as they came to be called. These marketing units sold and distributed meat directly from refrigerator cars in hamlets and villages along the railroad lines in rural areas.

Both Armour and Swift had enough branch houses and car lines to group them under some twenty-five district superintendents, and so employed a level of middle managers between the operating units and the Chicago headquarters. The managers in these regional offices supervised the performance of the branches in their territories, coordinated the work of the salesmen soliciting the retailers, and reviewed the advertising of the local branches. They also made direct sales to a small number of indepen- dent commission wholesalers. The branch house network, the most signifi- cant innovation of the industry’s leading innovator, Gustavus Swift, remained the most vital component in these giant food-processing enter- prises.

The critical task of coordinating the flow of fresh, very perishable meat was handled at the selling departments’ headquarters. In coordinating and controlling this flow Armour and the other packers relied heavily on cost and other statistical figures provided at the packing plants by their ac- counting division. The nature of and reason for such controls was well expressed in the Bureau of Corporations report published in 1905:

On account of their perishability the handling of fresh meat is a peculiarly delicate business. The packer aims to get as high a price as possible, but he must sell the entire product before it spoils. Differences in quality of animals and of their products are so great that the closest supervision of the central office is necessary to enforce the exercise of skill and sound judgment on the part of the agents who buy stock and the agents who sell meats. With this object, those branches of the selling and accounting department of the packing companies which have charge of the purchasing, killing, dressing, and selling of fresh meats are organized in a most extensive and thorough manner. The central office is in constant telegraphic correspondence with the distributing houses with a view to adjusting the supply of meat and the prices as nearly as possible to the demand.33

Figure 8. Organization chart of Armour & Company, 1907

Source: System, 1 2 : 22 0 (Sept. 1907)

Such administrative coordination was carried out in the following way. Chicago headquarters assigned each branch house and car line a packing plant as their supplier. The managers of each of these distributing units telegraphed their orders daily to their supplying plant, with all orders going through the central Chicago office. If the supplying plant was short, Chicago would fill orders from another plant. If that supplier had surpluses, Chicago allocated such surpluses to branch houses or car lines other than its designated receivers. Even after the beef had left the packing house, its distribution was carefully administered. As the Bureau of Corporations report noted: “The head offices are in constant telegraphic communication with the branch houses and commission agents during the progress of the sale of each carload of beef, obtaining information and giving advice.”34 Not surprisingly, Armour and Swift had expenditures of $200,000 a year for telegraphic service, a large proportion of which came from selling dressed beef. As in the case of railroads a generation earlier, the managers at headquarters were soon employing the data used in coordinating flows to evaluate managerial performance. “The long and elaborate account sales [sic] which the branch house managers and commission agents send in for each car of beef,” Bureau investigators reported, “must be carefully checked by the company, not merely to verify the accuracy of the entries, but also for the purpose of criticizing the soundness of the judgment of the branch house manager in his method of disposing of the beef.” To collect, collate, and distribute such data, Armour’s accounting department set up its branch house and purchasing sections as early as 1889.

The basic figure used in coordinating, supervising, and evaluating the work of the managers as well as in setting prices and regulating flows was what the packers called “dressed” (or sometimes “test” or “red”) costs. For each “bunch” of cattle killed, the packing plant recorded the live weight and price paid, labor costs, overhead costs, and the weight and quality of the meat, hides, and fat.35 These data provided the unit cost for processing or “dressing” that parcel of cattle. The addition of freight charges and overhead gave the “dressed” cost at the branch house. These “dressed” costs were then compared at each market with average sales prices. The resulting margins between costs and sales prices, telegraphed to Chicago headquarters and the packing plants, became a guide to purchasing in the stockyards. If margins dropped, purchasing and slaughtering slowed. If they increased, so did cattle buying and plant output.

Such data, which provided the packers with essential control over flows, gave them an accurate picture of their prime costs but little more. Overhead, administrative, and selling costs appear to have been little more than rough estimates. Selling costs, for example, were simply a flat per- centage of sales—“the more common rate being 5 percent.”36 Nor did the packers have a clear view of their assets. They, like American Tobacco, used the current railroad practices of renewal accounting. They charged “to operating expenses, not merely minor repairs, but also from time to time large outlays for reconstruction and improvements.”

This concentration on prime costs and the use of renewal accounting meant that the packers had little information on the rate of return they re- ceived on invested capital. They did not try to allocate costs to different parts of their businesses and had no way of knowing accurately the profits of their different lines. The Bureau of Corporations admitted that it was “impossible” for their investigators or the companies “to calculate with any approach to accuracy the percentage of return which the large western packers are able to secure on the capital invested in the beef branch of their business.” In the packing business the best test of managerial performance continued to be the ability to maintain reasonable margins and to move the goods as quickly as possible. It was not based on the managers’ ability to maintain and expand a predetermined rate of return on investment.

The packers differed from other large processors of agricultural products in that they owned and operated much more extensive transportation facilities and exploited more fully these facilities and their processing capacity. Their transportation departments were, in fact, among the largest transportation enterprises in the world. By 1903 Armour’s transportation department owned and operated 13,600 refrigerated cars (of which 1,650 were for carrying fruit) and Swift 5,900. The total owned by the Big Six was over 2 5,ooo.37 At an estimated cost of $1,000 a car, this represented a substantial investment. By 1903 Armour’s department was operating over 300 million car-miles a year.

Headed by a general manager, the transportation department was di- vided into two divisions.38 One maintained and serviced the fleet of re- frigerated cars and the icing stations throughout the country. The other, the traffic department, was responsible for scheduling the cars needed to carry the flow of livestock into the plant and the massive movement of dressed and processed meat from the plant to the retailers. In carrying out their task, the managers worked closely with those in the sales, purchasing, and manufacturing departments.

Because the company owned its own rail cars, it was able to schedule flows more precisely and with more certainty than if it had to depend on the traffic departments of railroads to supply them. Therefore, although the packers had been forced originally to build their own cars because of the railroads’ refusal to do so, they soon found their control of such facilities invaluable adjuncts to their business. It was for this same reason— to assure a more certain coordination of flows of raw materials and finished goods—that Standard Oil and its smaller competitors had before 1900, and a number of chemical, glass and some other food companies had by 1910, come to own and schedule their own fleets of railroad cars.

The heavy investment in transporting, distributing, processing, and purchasing facilities proved to be a powerful goad to expansion. The process of growth for the purpose of using existing facilities more in- tensively was more evolutionary at Armour and the other large packers than it was at American Tobacco. Even before 1890 the packers had begun to extend their sales organization overseas, using their own refrigerated ships and setting up depots in major seaports.™ However, although they had salaried sales and distribution managers abroad, they did not set up a branch office network comparable to those in the United States until the first decade of the twentieth century. In order to make fuller use of their production facilities, they quickly began to process pork, lamb, and other meat products.40 Almost at once they became leaders in the canned meat industry where small firms had already pioneered, particularly Wilson and Company (which later joined Schwartzchild & Sulzberger) and Libby, McNeil and Libby (which later became associated with Swift). Then Armour and the others began to use their canning facilities for packing salmon, sardines, tuna, evaporated milk, and vegetables. All such canned products were sold through the branch-house distributing organization.

The company set up separate organizations to distribute and market products that could not be sold through their existing marketing facilities. At Armour the largest of these operations was the fertilizer division, where a general manager supervising sixteen plants had his own sales, production, and accounting departments.41 He thus had all the facilities necessary to operate an autonomous business of his own. Indeed, it was the success of such integrated divisions at Armour and Swift that caused many small fertilizer companies to merge in the 1890s and then to build comparable administrative structures. Other by-products with a smaller volume of production and sales, such as glue, soap, oleo oil, stearin, and other products derived from animal fat, were grouped under the general manager of the by-products department. The marketing men in this department were responsible for coordinating the flow. But precisely because these units did not have large marketing organizations for their own specific products, they had difficulty competing with large integrated enterprises such as Procter & Gamble and American Cotton Oil.

At Armour and its major competitors the desire to make as full use of the facilities in distribution as those in production led to further growth of the firm. The packers began to use refrigerated cars and storage rooms at the branch houses to distribute other perishable products such as butter, eggs, poultry, and fruit. But in order to obtain these products, they had to create new purchasing units. Soon, the company had built, as it had in the fertilizer business, a separate autonomous enterprise to obtain, sell, and coordinate the flow of these perishable items from the farmer to the re- tailer. This produce department had its own large buying division with a number of refrigerated warehouses which purchased, stored, and as- sembled its product lines. Its traffic division with offices next to those of the larger transportation department allocated cars; while its sales organi- zation, which used the company’s branch-house facilities, handled its own advertising and delivery to retailers, and generated its own daily market orders and buying estimates.

In these ways, then, the pressure to keep the existing facilities fully used caused the managers at Armour and other packers to push the enterprise into obtaining additional facilities. Such expansion, in turn, required the creation of new, autonomous managerial suborganizations to evaluate, coordinate, and plan the activities of these units. This process of growth became an increasingly common one during the twentieth century for the large integrated industrial enterprises in the United States.

During the 1890s, the meat packers had created as complex an organiza- tional structure as those earlier developed by railroad systems. Yet their top management paid little attention to systematic long-term planning and investment decisions. One reason was that such decisions continued to be made by a small number of top executives who spent nearly all their time in day-to-day activities.

Well into the twentieth century the Armours, Swifts, Morrises, and Cudahys continued to manage as well as to own their massive enterprises. Except for the Swifts the founders or their families still held nearly all the stock of their respective companies.42 Swift was the exception, because the Swift brothers had used stock to obtain branch houses. They paid wholesalers who joined them with shares of Swift & Company. But even the Swift family continued to hold a controlling block of stock in their company.

As owner-managers these entrepreneurs paid little attention to strategic planning and the long-term allocation of resources. In 1907 J. Ogden Armour’s daily routine was still totally taken up by reading operational reports and issuing orders to buying, processing, and selling departments.43 All department heads reported directly to him. In this work he had little or no staff assistance. The only specialized nonoperating officer he con-400 ] Management and Growth of Modern Industrial Enterprise suited was the head of the legal department—an office formally estab- lished only in 1897. The senior executives therefore had little time for such things as strategic planning.

Another reason Armour or another of the packers did not plan a stra- tegic campaign of conquest similar to Duke’s was that in their industry no single firm had acquired a dominant position. The leaders had built their integrated organizations almost simultaneously. Each realized that he had little chance of driving out the others, except at excessive cost. So like the railroads they decided to cooperate rather than to compete in order to keep their expensive facilities full and running steadily.

As in transportation, cooperation resulted first in informal and then formal pools. The formal cartel operated from 1893 to 1902, with the ex- ception of one year, 1897. Its object was to keep the meat moving from the yards to the retailers as smoothly and evenly as possible and at an ac- ceptable margin between cost and price. It was operated in a personal manner. The president and the heads of the beef departments met every Tuesday in Chicago to decide the coming week’s allocations based on costs, output, sales, and margins as reported daily by their accounting de- partments.44 In these decisions Swift and Armour took the lead.

After such pooling became clearly illegal, the packers considered merger as an alternative. In April 1902, a month before the government filed a formal suit under the Sherman Act against the Northern Securities Com- pany, the packers began negotiations to merge their enterprises into a giant holding company. The investment banking house of Kuhn, Loeb agreed to finance a $500 million merger to be known as the National Packing Company.45 After its promoters had opened negotiations with some local companies, the plan fell through. Kuhn, Loeb backed down. One reason was financial. The merger movement by 1902 had pretty well run its course. The market for such a volume of securities was clearly limited. The other was legal. If the government won its case against the Northern Securities Company, the proposed holding company would be particularly vulnerable. The packers then modified their plans. A National Packing Company was formed, but on a much smaller scale. Made up of Hammond and four small firms, it became an operating rather than a holding company, with its stock owned by Swift, Armour, and Morris. The personnel and activities of the smaller firms were consolidated into the Hammond operating organization. Its three owners used National’s headquarters as a central post to disseminate information on “dressed” costs, closing prices, and margins. In pricing and output Cudahy and Schwartzchild & Sulzberger began to follow National’s lead, even though they had no formal con-nection with it.

By 1910, however, the packers decided they no longer needed National Packing. They were quite willing to disband it at the request of the Justice Department without making a court case, even though they had survived an earlier antitrust action. By then they had learned to operate in the domestic market without such formal arrangements. They knew each other’s current costs, and they knew the current demand and available supplies and adjusted their flows accordingly. They had the information available and the technique perfected to do without collusion what they had previously done through formal cooperation. The smaller companies now followed the price leadership of Armour and Swift. The packers continued to compete by providing regular, prompt delivery and by advertising rather than by price. And they continued to grow by concentrating on using their manufacturing and distribution facilities more intensively and by enlarging their overseas markets. In other words, during the first decade of the twentieth century the packers learned to compete and grow in the modern oligopolistic manner.

In that decade the owner-managers of Armour and Swift were becom- ing, like Duke at American Tobacco, more concerned with foreign than domestic business. After 1900 the domestic demand had become so large that the packers no longer had supplies to meet the growing foreign de- mand. The two packers responded by opening new sources for supplies in South America. During that decade they obtained packing plants in Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil to process for the European markets.46 At the same time they acquired the necessary transportation facilities and quickly enlarged branch-house networks in Europe. The largest share of the packers’ resource allocation in the years preceding World War I went to building the same type of integrated network to coordinate the flow of meat from the Argentine Pampas to the European cities that they had fashioned two decades earlier in the United States to connect the western plains with the eastern seaboard.

The experience of the packers paralleled that of brewers who competed in the national market, United Fruit, and other processors and shippers of perishable products. The meat packers’ story has a wider significance however. It tells much about the competition between and the growth of vertically integrated enterprises that came into being in order to coordinate high-volume flows from the raw materials suppliers to the ultimate consumers. For such firms price leadership without formal collusion became the standard practice. Profits resulted from continued cost cutting, improved administrative coordination, greater use of existing facilities, and expansion overseas. Such growth into new products and new markets often required the building of new sub organizations to coordinate the flow of goods.

Even before the First World War this pattern of competition and growth had appeared in oil, chemical, rubber, glass, fabricated metals, and paper industries, where the nature of the processes of production and distribution made vertical integration and administrative coordination profitable. Whether the new large enterprises integrated after mergers or whether they expanded through internal growth, they maintained their dominance by means of efficient administrative coordination. Like the packers, they purchased and operated their own fleets of tank cars, ships, and other transportation facilities. They developed a full line of products for their major market, energetically developed by-products, and set up new offices to supervise the flow of these goods to new markets. By World War I nearly all had laboratories to improve and develop new and existing products, as well as processes. They, too, expanded overseas. At home and abroad they came to compete in the modern oligopolistic manner, by means of product improvement, product differentiation, service, and im- proved coordination, rather than by price.

For example, in the oil industry Standard Oil was the price leader before the dismemberment of 1 9 1 1 . After that date, the industry’s historians point out, the largest of the former Standard Oil companies, particularly those of New Jersey and New York, “continued to play a leading role in the determination of prices in their respective marketing territories.”47 They rarely resorted to price wars, which the courts had come to define as “predatory practices.” And where they led, Texaco, Gulf, Pure, Tidewater, and many others followed. Instead of competing for a share of the market on price, the companies advertised their brands of products with catchy slogans and improved the facilities and services at the growing number of retail gasoline stations which these companies came to own or to franchise. Since the 1880s Standard and the other oil companies had, like the packers, built large by-products trades. And from the beginning of the industry, Standard and its competitors operated in global markets.

Source: Chandler Alfred D. Jr. (1977), The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, Harvard University Press.