Although the differences among analysts emphasizing one or another element are partly a matter of substantive focus, they are also associ- ated with more profound differences in underlying philosophical assumptions. While it is not possible to do full justice to the complexity and subtlety of these issues, I attempt to depict the differences in broad outline. Two matters are particularly significant: (1) differences among analysts in their ontological assumptions—assumptions concerning the nature of social reality; and (2) differences involving the extent and type of rationality invoked in explaining behavior.

1. Regulative and Constitutive Rules

Truth and Reality

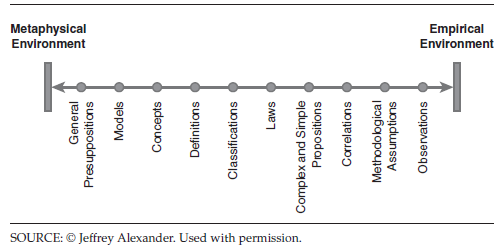

Varying ontological assumptions underlie conceptions of institu- tional elements. Thus, it is necessary to clarify one’s epistemological assumptions: How do we understand the nature of scientific knowl- edge? My position on these debates has been greatly influenced by the formulation advanced by Jeffrey C. Alexander (1983, Vol. 1), who pro- vides a broad, synthetic examination of the nature and development of theoretical logic in modern sociological thought. Following Kuhn (1970), Alexander adopts a postpositivist perspective viewing science as operat- ing along a continuum stretching from the empirical environment on the one hand to the metaphysical environment on the other (see Figure 3.1). At the metaphysical end reside the most abstract general presup- positions and models associated with more theoretical activity. At the empirical end, one finds observations, measures, and propositions. The continuum obviously incorporates numerous types of statements, rang- ing from the more abstract and general to the more specific and particu- lar. But, more important, the framework emphasizes that, although the mix of empirical and metaphysical elements varies, every point on the continuum is an admixture of both elements. “What appears, concretely, to be a difference in types of scientific statements—models, definitions, propositions—simply reflects the different emphasis within a given statement on generality or specificity” (Alexander 1983, Vol. 1: 4).

Figure 3.1 The Scientific Continuum and Its Components

The postpostivist conception of science emphasizes the fundamen- tal similarity of the social and physical sciences—both are human attempts to develop and test general statements about the behavior of the empirical world. It rejects both a radical materialist view that espouses that the only reality is a physical one, and also the idealist (and postmodernist) view that the only reality exists in the human mind. It also usefully differentiates reality from truth, as Rorty (1989) observes:

We need to make a distinction between the claim that the world is out there and the claim that truth is out there. To say that the world is out there, that it is not our creation, is to say, with common sense, that most things in space and time are the effects of causes which do not include human mental states. To say that truth is not out there is simply to say that where there are no sentences there is no truth, that sentences are elements of human languages, and that human languages are human creations. (pp. 4–5)

Social Reality

Although the physical and social sciences share important basic features, it is essential to recognize that the subject matter of the social sciences is distinctive. In John Searle’s (1995: 1, 11, 13) terminology, por- tions of the real world, while they are treated as “epistemically objec- tive” facts in the world, “are facts only by human agreement.” Their existence is “observer-relative”: dependent on observers who share a common conception of a given social fact. Social reality is an important subclass of reality.8

Earlier in our discussion of cultural-cognitive elements, I intro- duced the concept of constitutive processes. Now we are in a position to develop this argument. Social institutions refer to types of social reality that involve the collective development and use of both regulative and constitutive rules. Regulative rules involve attempts to influence “ante- cedently existing activities”; constitutive rules “create the very possibil- ity of certain activities” (Searle 1995: 27). Constitutive rules take the general form: X counts as Y in context C; for example, an American dollar bill counts as legal currency in the United States. “Institutional facts exist only within systems of constitutive rules” (p. 28). In general, as the label implies, scholars embracing the regulative view of institu- tions focus primary attention on regulative rules; for example, they assume the existence of actors with a given set of interests and then ask how various rule systems, manipulating sanctions and incentives, can affect the behavior of these actors as they pursue their interests. Cultural-cognitive scholars stress the importance of constitutive rules: They ask what types of actors are present, how their interests are shaped by these definitions, and what types of actions they are allowed to take. They thus differ in their ontological assumptions or, at least, in the ontological level at which they work.

The anthropologist David Schneider (1976) usefully describes the relation of constitutive culture to social norms:

Culture contrasts with norms in that norms are oriented to patterns for action, whereas culture constitutes a body of definitions, prem- ises, statements, postulates, presumptions, propositions, and per- ceptions about the nature of the universe and man’s place in it. Where norms tell the actor how to play the scene, culture tells the actor how the scene is set and what it all means. Where norms tell the actor how to behave in the presence of ghosts, gods, and human beings, culture tells the actor what ghosts, gods, and human being are and what they are all about. (pp. 202–203)

Constitutive rules operate at a deeper level of reality creation, involving the devising of categories and the construction of typifica- tions: processes by which “concrete and subjectively unique experi- ences . . . are ongoingly subsumed under general orders of meaning that are both objectively and subjectively real” (Berger and Luckmann 1967: 39). Such processes are variously applied to things, to ideas, to events, and to actors, and are organized into hierarchical linked arrangements and elaborate systems for organizing meaning. Games provide a ready illustration. Constitutive rules construct the game of football as consisting of things such as gridiron and goal posts and events such as first downs and offsides (see D’Andrade 1984). Simi- larly, other types of constitutive rules result in the social construction of actors and associated capacities and roles: in the football context, the creation of quarterbacks, coaches, and referees. Regulative rules define how the ball may legitimately be advanced or what penalties are asso- ciated with what rule infractions. Thus, cultural-cognitive theorists amend and augment the portrait of institutions crafted by regulative theorists. Cultural-cognitive theorists insist that games involve more than rules and enforcement mechanisms: They consist of socially constructed players endowed with differing capacities for action and parts to play. Constitutive rules construct the social objects and events to which regulative rules are applied.

Such processes, although most visible in games, are not limited to these relatively artificial situations. Constitutive rules are so basic to social structure, so fundamental to social life that they are often over- looked. In our liberal democracies, we take for granted that individual persons have interests and capacities for action. It seems natural that there are citizens with opinions and rights (as opposed to subjects with no or limited rights), students with a capacity to learn, fathers with rights and responsibilities, and employees with aptitudes and skills. But all of these types of actors—and a multitude of others—are social con- structions; all depend for their existence on constitutive frameworks that, although they arose in particular interaction contexts, have become reified in cultural rules that can be imported as guidelines into new situations (see Berger and Luckmann 1967; Gergen and Davis 1985).

Moreover, recognition of the existence of such constitutive pro- cesses provides a view of social behavior that differs greatly from lay interpretations or even from those found in much of social science. As Meyer, Boli, and Thomas (1987) argue:

Most social theory takes actors (from individuals to states) and their actions as real, a priori, elements. [In contrast] we see the “existence” and characteristics of actors as socially constructed and highly problematic, and action as the enactment of broad institutional scripts rather than a matter of internally generated and autonomous choice, motivation and purpose. (p. 13)

In short, as constitutive rules are recognized, individual behavior is seen to often reflect external definitions rather than (or as a source of) internal intentions. The difference is nicely captured in the anecdote reported by Peter Hay (1993):

Gertrude Lawrence and Noel Coward were starring in one of the latter’s plays when the production was honored with a royal visit. As Queen Elizabeth entered the Royal Box, the entire audience rose to its feet. Miss Lawrence, watching from the wings, mur- mured: “What an entrance!” Noel Coward, peeking on tip-toe behind her, added “What a part!” (p. 70)

The social construction of actors also defines what they consider to be their interests. The stereotypic “economic man” that rests at the heart of much economic theorizing is not a reflection of human nature, but a social construct that arose under specific historical circumstances and is maintained by particular institutional logics associated with the rise of capitalism (see Heilbroner 1985).9 From the cultural-cognitive perspective, interests are not assumed to be natural or outside the scope of investigation; they are not treated as exogenous to the theo- retical framework. Rather, they are recognized to be endogenous, arising within social situations, as varying by institutional context and as themselves requiring explanation.

The social construction of actors and their associated activities is not limited to persons. Collective actors are similarly constituted, and come in a wide variety of forms. We, naturally, will be particularly interested in the nature of those institutional processes at work in the constitution of organizations and organization fields, processes consid- ered in later chapters.

In their critique of the pillars framework, Phillips and Malhotra (2008) argue that because the different elements operate at varying ontological levels, they cannot be combined into an integrated frame- work. They propose that “authentic” institutional analysis involves exclusive attention to the cultural-cognitive elements:

The fact that coercive and normative mechanisms are externally managed by other actors makes them very different from the taken-for-grantedness of cognitive mechanisms. Where coercive and normative mechanisms result in strategic action and often resistance, cognitive mechanisms function by conditioning thinking. (p. 717)

But is this true? In a world of words, many of the most important strategies involve choices as to how to frame the situation, how to con- struct a powerful narrative, how to brand the product. In contested situations, some of the most effective weapons available to contenders involve how to define the actions, the actors, and their intent. Are we seeking “Black power” or “civil rights”?

Cultural-cognitive elements are amenable to strategic manipula- tion. They are also subject to deliberative processes under the control of regulative and normative agents. Thus, members of the legislature or the judicial branch can change the rights and powers of individual and collective actors. Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that corporations have political rights allowing them to exercise free- dom of speech, including unrestricted expenditure of funds for politi- cal action committees. And professional authorities regularly create new institutions: new concepts, distinctions, and typologies that shape the types of measures we use; the kinds of data we collect; and the interpretations we make (Espeland and Sauder 2007; Scott 2008b). In short, there are important differences among the pillars, as I have labored to explicate. I have attempted to construct what social theorist Charles Tilly (1984) defines as an encompassing theoretical frame- work, one that examines theories sharing broad objectives and attempts not simply to argue that they employ provide differing approaches, but to explicate the ways in which the approaches vary. I continue to believe that such a framework provides a fruitful guide for institu-tional analysis.

2. Rational and Reasonable Behavior

Theorists make different assumptions regarding how actors make choices: what logics determine social action. As discussed earlier and in Chapter 1, Weber defined social action so as to emphasize the impor- tance of the meanings individuals attach to their own and others’ behavior. For Weber and many other social theorists, “the central ques- tion that every social theory addresses in defining the nature of action is whether or not—or to what degree—action is rational” (Alexander 1983, Vol. 1: 72). A more basic question, however, is how is rationality to be defined? Social theorists propose a wide range of answers.

At one end of the spectrum, a neoclassical economic perspective embraces an atomist view that focuses on an individual actor engaged in maximizing his or her returns, guided by stable preferences and pos- sessing complete knowledge of the possible alternatives and their con- sequences. This model has undergone substantial revision in recent decades, however, as over time economists have reluctantly acknowl- edged limitations on individual rationality identified by psychologists such as Tversky and Kahneman (1974), as described in Chapter 2. Validated by a Nobel Prize in economics (in 2002), this work has been incorporated into the mainstream as behavioral economics. Perhaps over- stating the matter, a review of Kahneman’s (2011) recent book concludes that his empirical investigations of human decision making “makes it plain that Homo economicus—the rational model of human behavior beloved of economists—is as fantastical as a unicorn” (The Economist 2011: 98). Nevertheless, this model, perhaps wearing a somewhat more modest cloak, continues to pervade much economic theorizing.

Embracing a somewhat broader set of assumptions, neoinstitu- tional analysts in economics and rational choice theorists in political science (e.g., Moe 1990a; Williamson, 1985) utilize Simon’s (1945/1997: 88) model of bounded rationality, which presumes that actors are “intendedly rational, but only boundedly so.” These versions relax the assumptions regarding complete information and utility maximization as the criterion of choice, while retaining the premise that actors seek “to do the best they can to satisfy whatever their wants might be” (Abell, 1995: 7). Institutional theorists employing these and related models of individual rational actors are more likely to view institutions primarily as regulative frameworks. Actors construct institutions to deal with collective action problems—to regulate their own and others’ behaviors—and they respond to institutions because the regulations are backed by incentives and sanctions. A strength of these models is that rational choice theorists have “an explicit theory of individual behavior in mind” when they examine motives for developing and consequences attendant to the formation of institutional structures (Peters 1999: 45; see also Abell 1995). Economic theorists argue that, while their assump- tions may not be completely accurate, “many institutions and business practices are designed as if people were entirely motivated by narrow, selfish concerns and were quite clever and largely unprincipled in their pursuit of their goals” (Milgrom and Roberts 1992: 42).

From a sociological perspective, a limitation of employing an overly narrow rational framework is that it “portrays action as simply an adaptation to material conditions”—a calculus of costs and benefits— rather than allowing for the “internal subjective reference of action” that opens up potential for the “multidimensional alternation of free- dom and constraint” (Alexander 1983, Vol. 1: 74). Another limitation involves the rigid distinction in rational choice models made between ends, which are presumed to be fixed, and means. Sociological models propose, variously, that ends are modified by means, that ends emerge in ongoing activities, and even that means can become ends (March and Olsen 1989; Selznick 1949; Weick 1969/1979). In addition, rather than positing a lone individual decision maker, the sociological version embraces an “organicist rather than an atomist view” such that “the essential characteristics of any element are seen as outcomes of rela- tions with other entities” (Hodgson 1994: 61). Actors in interaction constitute social structures, which, in turn, constitute actors. The prod- ucts of prior interactions—norms, rules, beliefs, resources—provide the situational elements that enter into individual decision making (see the discussion of structuration in Chapter 4).

A number of terms have been proposed for this broadened view of rationality. As usual, Weber anticipated much of the current debate by distinguishing among several variants of rationality, including Zweckrationalität—action that is rational in the instrumental, calculative sense—and Wertrationalität—action that is inspired by and directed toward the realization of substantive values (Weber 1924/1968, Vol. 1: 24; see also Swedberg 1998: 36). The former focuses on means-ends con- nections; the latter on the types of ends pursued. Although Weber himself was inconsistent in his usage of these ideal types, Alexander suggests that they are best treated as analytic distinctions, with actual rational behavior being seen as involving an admixture of the two types. All social action involves some combination of calculation (in selection of means) and orientation toward socially defined values.10

A broader distinction has been proposed by March (1981), who dif- ferentiates between a logic of instrumentalism and a logic of “appropri- ateness” (see also March 1994; March and Olsen 1989), as noted earlier. An instrumental logic asks, “What are my interests in this situation?” An appropriateness logic stresses the normative pillar where choice is seen to be grounded in a social context and to be oriented by a moral framework that takes into account one’s relations and obligations to others in the situation. This logic replaces, or sets limits on, individual- istic instrumental behavior.

Cultural-cognitive theorists emphasize the extent to which behav- ior is informed and constrained by the ways in which knowledge is constructed and codified. Underlying all decisions and choices are socially constructed models, assumptions, and schemas. All decisions are admixtures of rational calculations and nonrational premises. At the micro-level, DiMaggio and Powell (1991) propose that a recognition of these conditions provides the basis for what they term a theory of prac- tical action. This conception departs from a “preoccupation with the rational, calculative aspect of cognition to focus on preconscious pro- cesses and schema as they enter into routine, taken-for-granted behav- ior” (p. 22). At the same time, it eschews the individualistic, asocial assumptions associated with the narrow rational perspective to empha- size the extent to which individual choices are governed by normative rules and embedded in networks of mutual social obligations.

The institutional economist Richard Langlois (1986b) proposes that the model of an intendedly rational actor be supplemented by a model of the actor’s situation, which includes, importantly, relevant social institutions. Institutions provide an informational-support function, serving as “interpersonal stores of coordinative knowledge” (p. 237). Such common conceptions enable the routine accomplishment of highly complex and interdependent tasks, often with a minimum of conscious deliberation or decision making. Analysts are enjoined to “pay attention to the existence of social institutions of various kinds as bounds to and definitions of the agent’s situation” (p. 252). Langlois encourages us to broaden the neoclassical conception of rational action to encompass what he terms “reasonable” action, a conception that allows actors to “prefer more to less [of] all things considered,” but also that allows for “other kinds of reasonable action in certain situations” including rule-following behavior (p. 252). Social action is always grounded in social contexts that specify valued ends and appropriate means; action acquires its very reasonableness from taking into account these social rules and guidelines for behavior.

As briefly noted in our consideration of a fourth pillar, recent scholars have suggested that contemporary theorizing would be advanced by resurrecting and updating pragmatism, a theory promul- gated during the late 19th and early 20th centuries by some of America’s most ingenuous social philosophers and social scientists, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, William James, Charles Peirce, and John Dewey. Among their central tenants were that (1) “ideas are not ‘out there,’ waiting to be discovered, but are tools . . . that people devise to cope with the world in which they find themselves,” and (2) that ideas are produced “not by individuals, but by groups of individuals—that ideas are social, . . . dependent . . . on their human carriers and the environment” (Menand 2001: xi). Indeed, as Strauss (1993) reminds us:

In the writings of the Pragmatists we can see a constant battle against the separating, dichotomizing, or opposition of what Prag- matists argued should be joined together: knowledge and practice, environment and actor, biology and culture, means and ends, body and mind, matter and mind, object and subject, logic and inquiry, lay thought and scientific thought, necessity and chance, cognitive and noncognitive, art and science, values and action. (p. 72)

Ansell (2005) suggests that pragmatists favored a model of deci- sion making that could be characterized as practical reason—recognizing that people make decisions in “situationally specific contexts,” draw- ing on their past experiences, and influenced by their emotions as well as their reason.

Source: Scott Richard (2013), Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, SAGE Publications, Inc; Fourth edition.