The starting point for analyzing industry evolution is the frame-work of structural analysis in Chapter 1. Industry changes will carry strategic significance if they promise to affect the underlying sources of the five competitive forces; otherwise changes are important only in a tactical sense. The simplest approach to analyzing evolution is to ask the following question: Are there any changes occuring in the in-dustry that will affect each element of structure? For example, do any of the industry trends imply an increase or decrease in mobility barriers? An increase or decrease in the relative power of buyers or suppliers? If this question is asked in a disciplined way for each com-petitive force and the economic causes underlying it, a profile of the significant issues in the evolution of an industry will result.

Although this industry-specific approach is the place to start, it may not be sufficient, because it is not always clear what industry changes are occurring currently, much less which changes might oc-cur in the future. Given the importance of being able to predict evo-lution, it is desirable to have some analytical techniques which will aid in anticipating the pattern of industry changes that we might ex-pect to occur.

1. PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE

The grandfather of concepts for predicting the probable course of industry evolution is the familiar product life cycle. The hypothe-sis is that an industry1 passes through a number of phases or stages- introduction, growth, maturity, and decline—illustrated in Figure 8-1. These stages are defined by inflection points in the rate of growth of industry sales. Industry growth follows an S-shaped curve because of the process of innovation and diffusion of a new prod-uct.2 The flat introductory phase of industry growth reflects the dif-ficulty of overcoming buyer inertia and stimulating trials of the new product. Rapid growth occurs as many buyers rush into the market once the product has proven itself successful. Penetration of the product‘s potential buyers is eventually reached, causing the rapid growth to stop and to level off to the underlying rate of growth of the relevant buyer group. Finally, growth will eventually taper off as new substitute products appear.

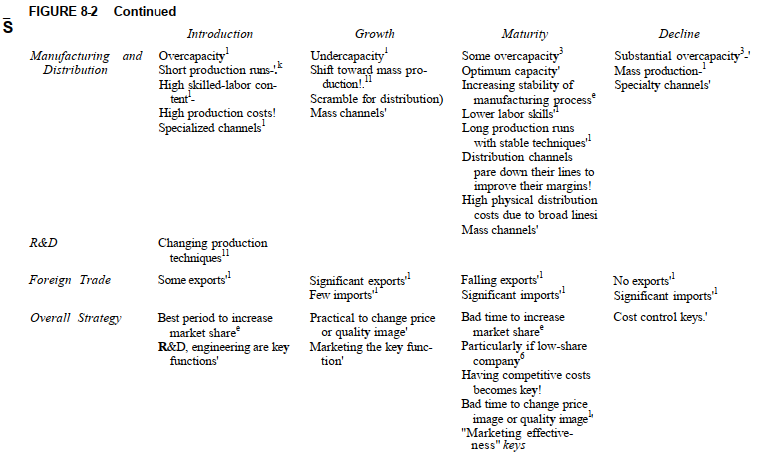

As the industry goes through its life cycle, the nature of compe-tition will shift. I have summarized in Figure 8-2 the most common predictions about how an industry will change over the life cycle and how this should affect strategy.

The product life cycle has attracted some legitimate criticism:

- The duration of the stages varies widely from industry to in-dustry, and it is often not clear what stage of the life cycle an indus-try is in. This problem diminishes the usefulness of the concept as a planning tool.

- Industry growth does not always go through the S-shaped pattern at all. Sometimes industries skip maturity, passing straight from growth to decl Sometimes industry growth revitalizes after a period of decline, as has occurred in the motorcycle and bicycle in-dustries and recently in the radio broadcasting industry. Some indus-tries seem to skip the slow takeoff of the introductory phase alto-gether.

FIGURE 8-1. Stages of the Life Cycle

FIGURE 8-2 Predictions of Product Life Cycle Theories About Strategy, Competition, and Performance

- Companies can affect the shape of the growth curve through product innovation and repositioning, extending it in a variety of 3 If a company takes the life cycle as given, it becomes an unde-sirable self-fulfilling prophesy.

- The nature of competition associated with each stage of the life cycle is different for different industri For example, some in-dustries start out highly concentrated and stay that way. Others, like bank cash dispensers, are concentrated for a significant period and then become less so. Still others begin highly fragmented; of these some consolidate (automobiles) and some do not (electronic compo-nent distribution). The same divergent patterns apply to advertising, R&D expenditures, degree of price competition, and most other in-dustry characteristics. Divergent patterns such as these call into seri–ous question the strategic implications ascribed to the life cycle.

The real problem with the product life cycle as a predictor of in-dustry evolution is that it attempts to describe one pattern of evolu-tion that will invariably occur. And except for the industry growth rate, there is little or no underlying rationale for why the competitive changes associated with the life cycle will happen. Since actual in-dustry evolution takes so many different paths, the life cycle pattern does not always hold, even if it is a common or even the most com-mon pattern of evolution. Nothing in the concept allows us to pre-dict when it will hold and when it will not.

2. A FRAMEWORK FOR FORECASTING EVOLUTION

Instead of attempting to describe industry evolution, it will prove more fruitful to look underneath the process to see what really drives it. Like any evolution, industries evolve because some forces are in motion that create incentives or pressures for change. These can be called evolutionary processes.

Every industry begins with an initial structure—the entry bar-riers, buyer and supplier power, and so on which exist when the in-dustry comes into existence. This structure is usually (though not al-ways) a far cry from the configuration the industry will take later in its development. The initial structure results from a combination of underlying economic and technical characteristics of the industry, the initial constraints of small industry size, and the skills and re-sources of the companies that are early entrants. For example, even an industry like automobiles with enormous possibilities for econo-mies of scale started out with labor-intensive, job-shop production operations because of the small volumes of cars produced during the early years.

The evolutionary processes work to push the industry toward its potential structure, which is rarely known completely as an industry evolves. Imbedded in the underlying technology, product character-istics, and nature of present and potential buyers, however, there is a range of structures the industry might possibly achieve, depending on the direction and success of research and development, marketing innovations, and the like.

It is important to realize that instrumental in much industry evolution are the investment decisions by both existing firms in the industry and new entrants. In response to pressures or incentives cre-ated by the evolutionary process, firms invest to take advantage of possibilities for new marketing approaches, new manufacturing fa-cilities, and the like, which shift entry barriers, alter relative power against suppliers and buyers, and so on. The luck, skills, resources, and orientation of firms in the industry can shape the evolutionary path the industry will actually take. Despite potential for structural change, an industry may not actually change because no firm hap-pens to discover a feasible new marketing approach; or potential scale economies may go unrealized because no firm possesses the fi-nancial resources to construct a fully integrated facility or simply be-cause no firm is inclined to think about costs. Because innovation, technological developments, and the identities (and resources) of the particular firms either in the industry or considering entry into it are so important to evolution, industry evolution will not only be hard to forecast with certainty but also an industry can potentially evolve in a variety of ways at a variety of different speeds, depending on the luck of the draw.

Source: Porter Michael E. (1998), Competitive Strategy_ Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press; Illustrated edition.