There are specific contemporary conditions that might account for the current dynamics of political change in organizations leading to the social fabric of a polyarchic model of power. First, there is the knowledge-intensive economy, which has been extensively documented and investigated (Adler 2001; Blackler 1995; Alvesson 1995), and which we examined in Chapter 3, which tends to stimulate the (re)development of collegial forms of organization. Particularly, the development of project-based organizations (which are the organizational corollary of knowledge- intensive economies) facilitates the production of new corporate internal subelites and possibly a new generation of managerial suboligarchs: project managers, busi- ness unit leaders, key account managers, and so on. Collegial organizations are defined by Waters as ‘those in which there is dominant orientation to a consensus achieved between the members of a body of experts who are theoretically equals in their level of expertise but who are specialized by area of expertise’ (1989: 956). Consequently, political forms should more and more take into account the inter- ests and power of internal subgroups generated by the needs of the organization, which comprise jobs occupied by an emerging new generation of executives (Cappelli and Hamori 2004).

Second, however mundane it might appear now, organizations are undoubtedly characterized by the pervasiveness of a culture of threat. The threat-intensive dis- course of leaders is not a new phenomenon as it has always been part of the leader- ship and institutional communication apparatus. But it is nowadays used in a downright political way, aiming to justify and eventually legitimize unacceptable or hardly understandable managerial decisions, such as collective dismissals in periods of high profitability. A contemporary interesting fact is the absence of ‘firestorms of protest’, the absence of actual official resistance when illegitimate decisions are made. While ‘victims’ may have to explain why they would oppose these decisions, business leaders don’t have to argue for them because of the supposed ‘rules of the game’. The contemporary culture of threat seamlessly enhances the power of uncertainty in the workplace. There is a political paradox lying behind these dynamics, comprising the fact that admitting powerlessness in the face of ‘external threats’ provides business elites with an easy way to refurbish a slightly severed legitimacy.

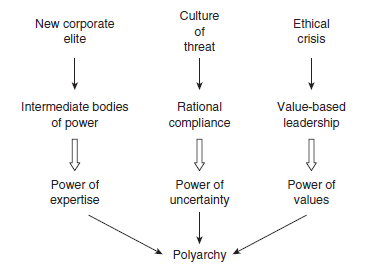

Figure 11.2 Some conditions of the generation of polyarchic structures of power

Third, evidently (and maybe even more mundane), the post-Enron period might be a highly favorable moment for any kind of critical opposition to contest the eternal evidence of contemporary elite power. One could therefore say that there is an urgent need for corporate elites to rejuvenate and restructure the polit- ical regimes of organizations, before any threat of being overthrown or overtly con- tested arises from the depths of organizations. Figure 11.2 sketches the mechanisms of the generation of polyarchy as the contemporary structure of power capable of bringing back the political performance of organizations onto an even keel. In a nutshell, the idea is that the three conditions outlined in the figure produce forms of power that might be difficult to combine in order to construct a congruent system of governance; in other words, a performing political regime. Weber stipu- lated clearly that one can never concretely observe a pure form of power and legit- imacy in organizations and that the only possible model in action is a model of political hybridity. It remains the case that it is hard to design the political form enabling the hybrid to be constructed without too much social turmoil.

Hybridization resides between expertise, uncertainty, and values as political and cultural pillars of a political form. The hybridizing process entails in itself a demo- cratic kind of social construction. For instance, combining compliant behaviors with the power of intermediate political bodies supposes a construction tolerating contestation and participation, which is what polyarchic forms might produce. In Dahl’s perspective, a polyarchy is a political regime that has been ‘substantially popularized and liberalized, that is, [it is] highly inclusive and extensively open to public contestation’ (1971: 8). It is an imperfect approximation of democracy, which is likely to arise when the mutual security of governors and governed is preserved. Put differently, in polyarchic regimes, the chances of contestation are greater when they do not hamper the power of elites to act according to the values and principles on the basis of which they hold power. Contestation is therefore possible when it does not create rivalries in the polity. Polyarchy is therefore gen- erated, thanks to a sort of political truce: oligarchs keep taking care of the political- strategic agenda and make ‘crucial’ decisions, while subordinates contribute (under the tutelage of local sub-oligarchs) the social construction of the local ‘rules of the game’, those which influence their personal fate.

As a result, polyarchy constitutes a political structure offering space to a great diversity of actors, while not disrupting oligarchic structures. The political ‘poly- archic’ model, therefore, defines organizations as sets of plural internal local oli- garchies, under the tutelary power of a central clique of business experts. It does not allow business leaders to get rid of the issue of inequality but it does allow them to govern the consequences of asymmetries by forcing diverse kinds of actors to be involved in political struggles about who gets power within the firm, to do what, and for whom. It is utterly derived from the Weberian polycratic model of organiza- tions: as Waters put it, ‘polycratic organizations are those in which power is divided among the members on a theoretically egalitarian basis but which is in principle capable of being aggregated in an “upward” direction’ (1993: 56).

Polyarchy is an ambivalent power structure enabling both the official recogni- tion of a plurality of members and political actors, the right to disagree with the leaders, and the simultaneous concentration of political power. The regulation between contestation and political concentration is operated through the action of intermediate bodies (the corporate subelites) whose duty is to foster participation and to ‘buffer’ the potential consecutive development of oppositional behaviors. That perspective is in line with a theory of political pluralism, according to which, ‘in a large complex society, the body of the citizenry is unable to affect the policies of the state’ (Lipset et al. 1956: 15). That is why a polyarchic structure of power necessitates the fragmentation of the political body: ‘democracy is most likely to become institutionalized in organizations whose members form organized or structured subgroups which, while maintaining a basic loyalty to the larger organi- zation, constitute relatively independent and autonomous centers of power within the organization’ (1956: 15). In a polyarchic structure, oligarchs strive to build a democratic plurality of actors while reinforcing unobtrusively the power of the inner circle. To sum up, a polyarchic structure of power is characterized by:

- soft and partly decentralized structures of governance with strict and relatively insuperable social and symbolic boundaries around oligarchic circles

- detailed social fragmentation through the multiplication of subgroups and the development of individualization, with strong intermediate bodies often artic- ulated around internal professions and subelites.

We suggest placing the polyarchic model into discrete categories to help situate it with respect to the other political structures we have outlined in Table 11.2. These categories are dependent both on the level of fragmentation of the organizational body (political plurality) and on the level of admissible contestation (deliberative culture. The discussion is summarized in Figure 11.3.

Figure 11.3 Variables Defining Polyarchy

Source: Clegg Stewart, Courpasson David, Phillips Nelson X. (2006), Power and Organizations, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1st edition.