In a broad way all of the six studies we will now examine attempt to throw more light on how organizations must vary if they are to cope effectively with different environmental circumstances. We will be interested in seeing how the results of these studies fit with our own findings. We will begin by looking at a significant piece of work done by Burns and Stalker, two industrial sociologists who had a major impact on the design of our study.

1. Burns and Stalker

Tom Burns and G. M. Stalker examined some 20 industrial firms in the United Kingdom For a detailed, in-depth study, this gave them an unusually good comparative sample. Their work focused on how the pattern of management practices in these companies was related to certain facets of their external environment. The particular external characteristics examined were the rates of change in the scientific techniques and markets of the selected industries. Next they explored the relationship between internal management practices and these external conditions to discover its effect on economic performance. The evidence was collected by extensive interviewing of key people in all 20 companies. No measurement methods were attempted. The enterprises were drawn from a variety of industries: a rayon manufacturer; a large engineering concern; a number of diverse Scottish firms, all interested in entering the electronics field; and eight English firms operating in different segments of the electronics industry. Fairly early in the fieldwork the authors were struck with the distinctly different sets of management methods and procedures they found in the different industries. These they came to classify as “mechanistic” or “organic.” The following paragraphs summarize this aspect of the study:

There seemed to be two divergent systems of management practice … One system, to which we gave the name “mech-anistic,” appeared to be appropriate to an enterprise operating under relatively stable conditions. The other, “organic,” appeared to be required for conditions of change. In terms of “ideal types” their principal characteristics are briefly the following.

In mechanistic systems the problems and tasks facing the concern as a whole are broken down into specialisms. Each individual pursues his task as something distinct from the real tasks of the concern as a whole, as if it were the subject of a subcontract. “Somebody at the top” is responsible for seeing to its relevance. The technical methods, duties, and powers attached to each functional role are precisely defined. Inter- action within management tends to be vertical, i.e., between superior and subordinate. Operations and working behavior are governed by instructions and decisions issued by superiors. This command hierarchy is maintained by the implicit assumption that all knowledge about the situation of the firm and its tasks is, or should be, available only to the head of the firm. Management, often visualized as the complex hierarchy which is familiar in organization charts, operates a simple control system, with information flowing up through a succession of filters, and decisions and instructions flowing downwards through a succession of amplifiers.

Organic systems are adapted to unstable conditions, when problems and requirements for action arise which cannot be broken down and distributed among specialist roles within a clearly defined hierarchy. Individuals have to perform their special tasks in the light of their knowledge of the tasks of the firm as a whole. Jobs lose much of their formal definition in terms of methods, duties, and powers, which have to be re- defined continually by interaction with others participating in a task. Interaction runs laterally as much as vertically. Communication between people of different ranks tends to resemble lateral consultation rather than vertical command. Omniscience can no longer be imputed to the head of the concern.

Our findings, in a general way, strongly support these con- clusions of Burns and Stalker. We systematically measured some of the structural attributes in which they observed variance, such as specificity of role description and reliance on formal rules. The environmental attribute that Burns and Stalker saw as causing the variance in management practice —the rate of change in technologies and markets—is one of the variables we have subjected to more systematic inquiry. We have found, as these findings suggest, that effective organizational units operating in stable parts of the environment are more highly structured, while those in more dynamic parts of the environment are less formal. The convergence of the findings of the two studies is considerable and important, even though Burns and Stalker’s was an exploratory study on which we drew to develop a more complex research model.

2. Woodward

Another study that influenced our design was conducted by Joan Woodward, one of England’s leading industrial sociologists, who in 1953 organized a research team and launched an investigation of the management process that, in various forms, is still continuing. This fruitful effort started with the question of whether “the principles of organization laid down by an expanding body of management theory correlate with business success when put into practice.” * In order to address this broad question, the researchers chose a rather uncommon and bold strategy. They selected a geographical area (South Essex) and studied virtually all the firms (91%) in the area that employed at least 100 people. Thus they secured a sample of 100 firms in widely diverse lines of business and proceeded to make a rather detailed examination of their characteristics, with particular attention to management practices. Early in the study they began to realize that there was no significant direct association between the management practices of these firms and their business efficiency or their size. Accordingly, Woodward commented:

The widely accepted assumption that there are principles of management valid for all types of production systems seemed very doubtful—a conclusion with wide implications for the teaching of the subject.

The researchers then sought some other basis of accounting for the variations in management practices. They found that when the firms were grouped according to their techniques of production and the complexity of their production systems, the more successful companies in each of these groupings followed similar management practices. The three broad groupings were (1) small- batch and unit production, e.g., special-purpose electronic equipment, custom-tailored clothing; (2) large-batch and mass production, e.g., standard electronic components, standard gasoline engines; and (3) process or continuous production, e.g., chemicals, oil refining. These three rough classifications were next broken down into 10 subgroups that, when arranged, formed a rough scale of the predictability of results and the corresponding degree of control over the production process. This ranged from low predictability for unit production to high for process produc- tion. As an example of predictability, the author points out:

Targets can be set more easily in a chemical plant than in even the most up-to-date mass-production engineering shops, and the factors limiting production are known more defi- nitely.

The general conclusion of this study, as we indicated in Chapter I, was that the pattern of management varied according to these technical differences. This was especially true of the more successful firms. In other words, economic success was associated with using management practices that suited in specified ways the nature of the various techniques of production. To be more specific, Woodward found, for ex-ample, that the number of levels in the hierarchy and the ratio of managers to hourly personnel increased directly with the predictability of production techniques. In a less measurable way, this same predictability factor appeared to influence the type of coordination required between the basic business functions, the level at which decisions were made, and the relative dominance or influence given to the various functional units.

Again we can see a general convergence of Woodward’s study and ours, even though her work centered on the organizational impact of variations in predictability only among production systems confronted with different technologies. Ours, on the other hand, emphasized the effect of variations in predictability on the tasks of all three of the basic units— production, marketing, and research—in industries that differed in the degree of market and scientific certainty, but that primarily used a process technology. Woodward’s study, like ours, concludes, “There can be no one best way of organizing a business,” and also provides strong leads as to how organizations must vary to be successful under different task and environmental conditions.7

3. Fouraker

With this third study of organizations we make an abrupt shift from the now-familiar approach of the sociologist to that of an experiment-oriented economist. We became aware of this work only after we had finished our own investigation. Fouraker began with an interest in the way organizations handle conflict and make economic decisions.8 Starting from a very few basic premises about human choice behavior, he logically deduced how two polar organizational types would respond to different choice situations posed by their environments. For preliminary tests of the propositions thus derived, he and his colleagues devised some ingenious small-scale experiments that simulated the organizational types and the environmen-tal circumstances. The experiments generally supported the theory.

Fouraker identified the two polar types as (1) the “L” or- ganization, composed of highly independent management motivated by their own aspirations and members who are rel- atively responsive to the aspirations of others; and (2) the “T” type, composed of responsive management and independent members. He hypothesized that the pure types, made up of all independents or all responsive people, would be unstable and would therefore drift into either L or T types.

Fouraker describes the L organization as:

. . . the classical or traditional form for organized human effort. The prospect (usually threatening) of a test with another group, or with nature, provides the common purpose for the original organization. The unity of interest implies that conflict within the group is dangerous and should be suppressed. This can be done, perhaps most easily, by selecting one person to act as the leader: his task is to select the appropriate goals or objectives for the group. . . .

The L organization is authoritarian. It does not generate the social mechanism or management skill to tolerate or contain internal conflict. Discipline is a necessity to insure harmony of interest and outlook. . . .

The L organization seems to be a very effective response to an institutional environment that is:

-

- Fairly stable, or not complex;

- Basically threatening.

The requirement for simplicity or stability stems from the leader’s role: the responsibility for choosing objectives is assigned to him, and no person can adjust to many simul- taneous demands. The human decision maker tends to ap- proach problems sequentially, not simultaneously.

The threatening aspect is required to insure discipline within the organization. Discipline, as we have seen, is necessary to maintain conformity of values.

The T organization, in marked contrast, consists:

… of members who are independent technical specialists, with a responsive management. This organizational form is of relatively recent origin, since it depends upon the existence of:

-

- Technical specialists in several dimensions,

- Whose special output must be coordinated to achieve the objectives of the organization.

Specialization emerges from, and causes, complex social situations. A complex task requires sustained attention, com- mitment, and interest. To master such a role one must learn, and ultimately become identified with, the task. Learning may lead to innovation and change. It is this contribution of the specialist which must be coordinated with the efforts of others in the T organization.

To pursue his specialty effectively, the member must be independent. His identification is with his task and with those who pursue similar tasks. His loyalty to his discipline, and to others who pursue it, may be stronger than his loyalty to his organization. He has more in common with similar specialists outside his organization than he has with specialists in different dimensions within his organization…

The management attempts to coordinate the efforts and output of these specialists. This requires a considerable ex- change of information, and therefore numerous communi- cations channels.

A T organization is likely to have very little in the way of hi- erarchy or chain of command. The status distinction between management and members will not be great. Generally the management will be drawn from the membership, and occa- sionally may return. The symbolic activity in the T organization is the committee meeting. The committee is the major means for coordinating the efforts of the specialists. As developed before, the committee is the institutional structure designed to secure commitment from members to a common set of objectives. . .

If the environment is favorable, the T organization is likely to be extremely productive and effective. The independent specialists can identify and pursue opportunities:

-

- Simultaneously;

- At a rapid rate.

This contrasts with the limitations of the independent leader of an L organization confronted with a favorable environ- ment.

In describing the T organization Fouraker addresses the central issue of our research: the problem of conflict resolution in complex organizations that need to combine and integrate the work of highly differentiated departments to cope with heterogeneous and dynamic environments.

One apparent difference between our study and Fouraker’s needs further examination. The characteristics of the immediate environment that we saw influencing the pattern of the organization were the rate of change and the predictability of events. Fouraker, however, focused on the “favorable or unfavorable” nature of the environment. These characteristics, on further analysis, are not so different as they might at first appear. To Fouraker a favorable environment was one in which new resources and new opportunities were becoming available for the organization to exploit. It would appear that this could only happen during a period of fairly rapid change. Likewise, his unfavorable environment is characterized by scarcity of resources, with a number of organizations struggling to secure their share. In such an environment, though the form of competition among organizations might change, the resources available, as he himself points out, are relatively static—hence, in our terms a stable, relatively unchanging environment. Given this rough reconciliation of the treatment of environmental characteristics in the two studies, we can see a general convergence of findings. In essence, both Fouraker’s study and our own point to the different organizational characteristics required for effectiveness under different environmental conditions. This convergence is partic-ularly interesting since Fouraker’s findings were derived the- oretically from a few basic premises and tested by some small- scale experiments, while ours were tested by empirical data from a sample of real organizations.

4. Chandler

In Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of Industrial Enterprises, Alfred Chandler, a historian, has created a landmark study of the evolution of large organizations.13 His method is the comparative analysis of the case histories of a few pioneering firms, supplemented by a brief review of the administrative histories of nearly 100 other major American companies. The basic thesis is deceptively simple: that organization structure follows from, and is guided by, strategic decisions. He develops this theme by selecting for extensive examination Du Pont, General Motors, Standard Oil (New Jersey), and Sears Roebuck. He chose these four companies as the innovators in creating a successful structure for administering the large multidimensional enterprise. Since their organizational innovations have subse- quently been widely imitated, as Chandler documents, these case histories broadened into the writing of institutional history. Chandler’s four case histories present a wealth of detail on the processes, often trial and error, by which these companies created their complex structures. For our present purpose we will draw on only some of his major conclusions.

Chandler sees new strategic choices arising from environ- mental changes: “Strategic growth resulted from an awareness of the opportunities and needs—created by changing population, income, and technology—to employ existing or expanding resources more profitably.” 14 He traces these strategic growth phases and their organizational ramifications in each of the companies and shows them as responses to changing environmental conditions. At one stage it was an expansion of volume” that led to the development of more special-ized jobs within the existing major functions. Then “growth through geographical dispersion” led to the establishment of territorial offices. Then the decision to become vertically in- tegrated led to expansion into “new types of functions,” with sharper differentiation of functional subsystems. Finally, di- versification through the development of “new lines of products” led to the establishment of various product divisions. Chandler explores how each of these choices to create new organizational units led into problems of integration that in turn required the development of new integrative (or, in his terms, administrative) structures. In fact, Chandler argues, “whenever the executives responsible for the firm fail to create offices and structure necessary to bring together effectively the several administrative offices into a unified whole, they fail to carry out one of their basic economic roles.” “ Throughout his study Chandler makes it clear that he sees different kinds of organization as necessary for coping effectively with different strategies and environments. Once again he cites the role of environmental change as the key factor in the choice of appropriate structure. One passage merits quoting at some length:

When the managers of a federation or combination of in- tegrated companies decided to coordinate, appraise, and plan systematically the work of their far-flung enterprise, they al- most always consolidated these activities into a single, cen- tralized, functionally departmentalized organization. As had the different mergers among the users of steel, such as Inter- national Harvester, Allis-Chalmers, American Locomotive, American Car and Foundry, and American Can, so many other combinations quickly disbanded their constituent firms and placed the sales, manufacturing, purchasing, or engineering activities of each within large, single-function departments. By 1909, only two or three of the nation’s largest industrial empires remained pure holding companies. More, like Standard Oil, American Tobacco, and the meat packers, continued to be legally both holding and operating compan- ies that administered both functional departments and multi- functional units, the latter usually having the legal form of a subsidiary corporation. The large majority, however, became administered through centralized, functionally departmentalized structures. For until Alfred P. Sloan created a new organization form at General Motors in 1920, this structure appeared to be the only one which could assure effective administrative control over a large industrial consolidation.

Yet the dominant centralized structure had one basic weakness. A very few men were still entrusted with a great number of complex decisions. The executives in the central office were usually the president with one or two assistants, sometimes the chairman of the board, and the vice presidents who headed the several departments. The latter were often too busy with the administration of the particular function to devote much time to the affairs of the enterprise as a whole. Their training proved a still more serious defect. Because these administrators had spent most of their business careers within a single functional activity, they had little experience or interest in understanding the needs and problems of other departments or of the corporation as a whole. As long as an enterprise belonged in an industry whose markets, sources of raw materials, and production processes remained relatively unchanged, few entrepreneurial decisions had to be reached. In that situation, such a weakness was not critical, but where technology, markets, and sources of supply were changing rapidly, the defects of such a structure became more obvious (italics added) .

Unlike the authors discussed previously, Chandler focused on the big and relatively infrequent strategic shifts in major corporations. In this sense he was not interested in the dif- ferences created by technologies, functional specialization, or environmental congeniality. Nevertheless, he concluded that different environmental conditions demanded different struc- tures. To Chandler also, it was the rate of environmental change (in “technology, markets, and source of supply”) that created the pressure for strategic and subsequently structural change. This historical study adds a new and different source of support to our enlarging picture of a theory that recognizes the contingent relationship of organizational characteristics to environmental demands.

5. Udy

Stanley Udy, a sociologist, employed a strikingly different way of examining the relationship between technology and organization structure. His purpose was “to seek broad gener- alizations about variation in organization structure relative to its social setting and the technology involved; and thus contribute to filling some of the ‘gaps’ in organization theory.” 17 He decided to study nonindustrial societies and drew his evidence primarily from the Human Relations Area Files, a compilation of anthropological descriptions of some 150 separate societies. From this source Udy developed a sample of 426 organizations that were carrying out various forms of agricultural work, hunting, fishing, collection, construction, manufacturing, and stock-raising. The societies represented all parts of the world, all major social groups, and several widely separated periods of history. He categorized the attributes of each of these organizations as well as the technology and the social setting.

Udy’s major conclusion had to do with the strength of the association between organization and technology:

Given a systematization of the possible range of variation of technological processes, it was found that certain aspects of authority, division of labor, solidarity, proprietorship, and recruitment structure could be predicted as to general trend from technology alone.

Across the full sweep of the known nonindustrial societies, Udy’s evidence clearly indicates that the facts of technology alone have a distinct and persistent influence on the structure of viable organizations.

Since Udy focused on organizations doing nonindustrial tasks, probably under relatively stable technical and market conditions, we cannot make direct and specific connections between his study and the others described here. His very broad-based work does, however, lend impressive support to the very general conclusion that organizations doing different tasks must be structured differently. Beyond this general point, his findings are particularly relevant for the design of any modern international organization operating in many cultural settings—the implication being that the technical requirements of the task cannot safely be ignored in designing the organization structure, even as allowance is made for cultural differences.

6. Leavitt

Shortly after World War II, at MIT, Alex Bavelas began another set of research studies that, in different forms, is still continuing. Although many others have contributed to the work, we will draw on the writing of Harold Leavitt, a social psychologist, who not only conducted some of the key experiments but has gone further than the others in considering the study’s implications for management practice.

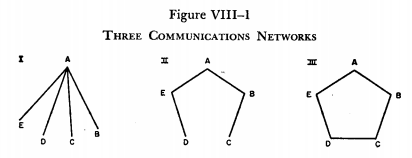

Leavitt and his colleagues used small groups to conduct various problem-solving activities under experimentally controlled conditions. The situation with which they experimented most extensively involved five people, each of whom was given a cup containing five different-colored marbles. In each cup was one marble that was duplicated in all five cups. The people were asked to exchange written communications until all five had learned which color marble they had in common. The experimental variations on this problem were introduced by controlling the channels available for communication (see Figure VIII—1). Using one of these three net-works, each group worked through the problem again and again, with a new set of marbles each time. Records were kept on a variety of results—the speed of reaching solutions; the number of messages sent; the number of errors made; etc. Without going further into the details of these experiments we can examine the findings. Leavitt has summarized them as follows:

It turns out that on these simple tasks Network I is far more efficient than II, which in turn is more efficient than III. In other words, groups of individuals placed in Network I within a very few trials solve these problems in an orderly, neat, quick, clear, well-structured way—with minimum mes- sages. In Network III, comparable groups solve the same problems less quickly, less neatly, with less order, and with less clarity about individual jobs and the organizational struc- ture—and they take more paper too.

However, when the researchers asked their subjects how they felt about their experiences, they got quite a different picture:

Network III people are happier, on the average, than II or I people (though the center man in Network I is apt to be quite happy).

Furthermore, the experimenters noticed:

. . . when a bright new idea for improvement of operations is introduced into each of these nets, the rapid accep-tance of the new idea is more likely in III than in I. If a member of I comes up with the idea and passes it along, it is likely to be discarded (by the man in the middle) on the ground that he is too busy, or the idea is too hard to implement, or “We are doing O.K. already; don’t foul up the works by trying to change everything!”

These observations led to an additional experimental change. The researchers introduced “noisy” marbles—marbles of unusual colors for which there were no common names. They again found that Network III had certain advantages over I:

. . . Network III is able to adapt to this change by devel- oping a new code, some agreed-on set of names for the colors. Network I seems to have much greater difficulty in adapting to this more abstract and novel job.

Leavitt summarized these findings:

So by certain industrial engineering-type criteria (speed, clarity of organization and job descriptions, parsimonious use of paper, and so on), the highly routinized, noninvolv- ing, centralized Network I seems to work best. But if our criteria of effectiveness are more ephemeral, more general (like acceptance of creativity, flexibility in dealing with novel problems, generally high morale, and loyalty), then the more egalitarian or decentralized Network III seems to work better.

These experimental findings fit very neatly with those of the present study and the others we have reviewed. It takes different kinds of organizations to perform different kinds of tasks efficiently. Of all the researchers we have reviewed, Leavitt sees the practical implications of these findings most clearly. He states:

. . . these developments suggest that we need to become more analytical about organizations, . . . and to allow for the possibility of differentiating several kinds of structures and managerial practices within them.

… I suggest that more and more we are differentiating classes and subclasses of tasks within organizations, so that questions about how much we use people, the kinds of people we use, and the kinds of rules within which we ask them to operate, all are being increasingly differentiated— largely in accordance with our ability to specify and program the tasks which need to be performed and in accordance with the kind of tools available to us.

* * * * *

. . . such a view leads us toward a management-by-task kind of outlook—with the recognition that many subparts of the organization may perform many different kinds of tasks, and therefore may call for many different kinds of managerial practices.

Leavitt also anticipated that the more differentiated organizations he sees emerging will “make for more problems of communication among sets of subgroups.” But his experiments did not permit him to explore these integration issues further. For our present purposes, however, the impressive point about this entire line of research is that studies on an ostensibly different topic, i.e., problem solving, and using a completely different methodology, i.e., small-group experimentation, should come up with such parallel findings about the relation between organizational attributes and the characteristics of different tasks. Leavitt’s phrase “management-bytask” serves well to capture the implications of this research.

The six studies we have reviewed have all been concerned with the various ways in which organizations, or major parts of organizations, are designed in terms of structure and important management practices, and the contingent relation this bears to tneir performance of different tasks in different environments. Of particular importance are some of the apparent differences our review highlights in the way the “external” conditions have been conceptualized and made opera-tional in each study. While there are differences in terminology, our review suggests that these are referring to the same underlying phenomena. Further conceptual and empirical work is needed, primarily on these external variables as a further test of our way of reconciling these studies. In any event, the studies, taken together, offer a formidable body of evidence that different organizational forms are required to cope effectively with different task and environmental conditions. All represent a strong new trend toward contingency and comparative studies of organizations that can serve to reconcile both the classical and the human relations approaches.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.