Because of differences in the demands of each environment and the related differences in integrative devices, each of these high-performing organizations had developed some dif-ferent procedures and practices for resolving interdepartmental conflict. However, certain important determinants of effective conflict resolution prevailed in all three organizations. We shall first examine the differences, then explore the similarities.

1. Differences in Conflict Resolution

The three effective companies differed in the relative influence of the various departments in reaching interdepartmental decisions. In the plastics organization it was the integrating department that had the highest influence. As we pointed out in Chapter III, this was consistent with the conditions in that organization’s environment. The high degree of differentiation and the complexity of problems made it necessary for the members of the integrating unit to have a strong voice in interdepartmental decisions. Their great influence meant that they could work effectively among the specialist managers in resolving interdepartmental issues.

In the food organization the research and marketing units had the highest influence. This too was in line with environmental demands and with the type of integrating device employed. Since there was no integrating unit, the two departments dealing with the important market and scientific sectors of the environment needed high influence if they were effectively to resolve conflicts around issues of innovation. However, as we also indicated earlier, there was ample evidence that within these two units the individuals who were formally designated as integrators did have much influence on decisions.

The pattern of departmental influence in the container organization contributed to the effective resolution of conflict for similar reasons. Here the members of the sales and production departments had the highest influence. This was appropriate, since the top managers in these two departments had to settle differences over scheduling and customer service problems. If these managers or their subordinates had felt that the views of their departments were not being given adequate consideration, they would have been less effective in solving problems and implementing decisions.

Here again we have been restating comparatively the findings reported in earlier chapters. Such reiteration helps us to understand how this factor of relative departmental influence contributes to performance in different environments. Each high- performing organization had its own pattern, but each of these was consistent with the demands of the most critical competitive issue.

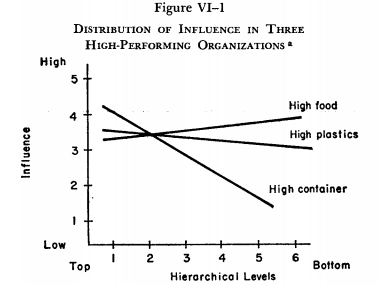

A second important difference among these three organiza- tions in respect to conflict resolution lay in the pattern of total and hierarchical influence. The food and plastics organizations had higher total influence than their less effective competitors, and, related to this, the influence on decisions was distributed fairly evenly through several levels (Figure VI-1) . The lower-level and middle-level managers who had the necessary detailed knowledge also had the influence necessary to make relevant decisions. In fact, they seemed to have as much influence on decisions as their top-level superiors. In the container industry, on the other hand, total influence in the high performer was lower than in the low performer, and the decision-making influence was significantly more concentrated at the upper management levels. This was consistent with the conditions in this environment. Since the in- formation required to make decisions (especially the crucial scheduling decisions) was available at the top of the organization, it made sense for many decisions to be reached at this level, where the positional authority also resided.

The importance of the differences in these influence lines can be better understood if we let some of the managers in each organization speak for themselves. In the plastics organization lower and middle managers described their involvement in decisions in this way:

- Lines fitted by least square method. The difference in the slope of the lines between the high-performing food and the high-performing container organization was significant at .001. This difference between the high-performing plastics and the high-performing container organization was significant at .005. There was no significant difference between the food and plastics organizations.

When we have a disagreement ninety-nine times out of a hundred we argue it out and decide ourselves. We never go up above except in extreme cases.

* * * * *

We have disagreements, but they don’t block progress, and they do get resolved by us. I would say on our team we have never had a problem which had to be taken up with somebody above us.

* * * * *

We could use these teams to buck it up to the higher man- agement, but I think this would be a weak committee and a weak individual, and I am not willing to give my freedom up. They give you all the rope you need. If you need their help, they are there; if you don’t need them, don’t bother them.

The last manager quoted went on to substantiate a point made by many of his colleagues: While lower and middle managers made most decisions at their own level, they also recognized that major issues, which might have implications for products other than their own, should be discussed with higher management. But this discussion always took place after they had agreed on the best course of action for their own products.

Over and over, these lower and middle managers indicated their own responsibility for decisions and their feeling that to ask their superiors to resolve conflicts would be to acknowledge their own inadequacy. A higher-level manager stressed that this was also the view at his level:

Top management has told these fellows, “We want you to decide what is best for your business, and we want you to run it. We don’t want to tell you how to run it.” We assume that nobody in the company knows as much about a business as the men on that team.

This same flavor was evident in remarks gathered in the food organization. Here, too, middle and lower managers stressed their own involvement in decisions.

Given these facts, the reader may be wondering about the activities of the upper echelons of management in the plastics and food organizations. If they were not involved in these decisions, what were they doing? While we made no detailed study of their activity, the data collected in interviews indicated clearly that they had plenty to keep them busy. First, they had the problems of administering their respective functional units. Second, they reviewed decisions made by their subordinates to make certain that the specialists working on one part of the product line were not doing anything that would adversely affect another part. In addi- tion, in their dynamic environments they were constantly concerned with the search for new and longer range oppor-tunities, which would fall outside the purview of any of their subordinates. In this regard we found in all the effective organizations the managers’ time horizons became longer ranged as one moved up the hierarchy. This tendency was particularly marked in the plastics and food organizations. This, too, suggested that top executives in the food and plastics organizations were heavily involved in longer range issues and problems.

The tone of comments by managers in the container organization about who made decisions was dramatically different from that in the other two organizations. We cited some examples in Chapter V, but a few more at this juncture may emphasize the contrast. The middle and lower managers in the container organization emphasized the chief executive’s and the other officers’ roles in decision making:

My primary contact is with [sales vice president and the chief executive]. This contact is around who we are going to give the containers to, because of our oversold position. They will determine which ones we are going to take care of Actually, what you really need though is [the chief executive’s] decision. I usually start out these kinds of conflicts with [the production scheduling manager], but when somebody has to get heard, it ends up with [the chief executive]. Usually I am in contact with him three or four times a day.

* * * * *

When there is a problem I try to tell [production vice president] the facts and make some recommendations. He makes the decisions or takes it up to [the chief executive]. He doesn’t get reversed very often. Sometimes he may say to me, “I agree with you, go ahead and do it,” and then [the chief executive] will change it.

The sales vice president explained his own involvement, emphasizing application of the available facts:

[The chief executive] holds a weekly scheduling meeting on Monday, which includes him, myself, the scheduling ager, and a couple of the sales managers, depending upon what the crucial problems are. The scheduling manager has prepared the schedule on Friday. On Monday we tear it apart. This business is like playing an organ. You’ve got to hit the right keys, or it just doesn’t sound right. The keys we play with are on the production schedule. In these meetings, though, the final decision rests with [the chief executive]. He gets the facts from us, and we influence the decision, but if there is any doubt, he decides.

All these comments serve to underline the differences in the distribution of influence between plastics and foods, on the one hand, and containers, on the other. These differences directly reflect differences in their respective environments.

2. Similarities in Conflict Resolution

So far, we have accentuated the important differences in these organizations in terms of the determinants of conflict resolution. Let us now look at some similarities. First, however, we should stress again that the differences actually stemmed from a fundamental similarity: Each of these organizations had developed conflict-resolving practices consistent with its environment.

The first major similarity among these organizations is in the basis of influence of the managers most centrally involved in achieving integration and resolving conflict. In all three organizations these managers, whatever their level, had repu- tations in the company for being highly competent and knowledgeable. Their large voice in interdepartmental decisions was seen as legitimate by other managers because of this competence. To return to the point made earlier, the positional influence of the managers assigned the task of helping to resolve interdepartmental conflict was consistent with their influence based on competence. Unlike the situation in some of the low- performing organizations, these two important sources of influence coincided in all these effective organizations. This point is illustrated by comments about the competence of the managers centrally concerned with conflict resolution in each organization.

In the container company, as we indicated earlier, the chief executive was regarded as extremely knowledgeable about the various facets of the business. As one manager expressed it:

The fact is, as I understand it, that he is almost a legend in the industry. He knows every function in this company better than any of the people who are supposed to be han- dling that function.

But the chief executive was not the only one who had this respect. Managers in this organization also emphasized the knowledge and ability of the other top executives. A research engineer described the competence of the research director:

I think another thing related to the close supervision I re- ceive is the nature of the [research director]. He is an excep- tional kind of guy, and he seems to know all the details and everything going on in the plant, and in the lab. He is con- tinually amazing people in this regard.

A similar point was made about the production vice president by one of his plant managers:

Oh yes, I hear from [the production vice president], but if he wants you, you are in trouble. You hear from him for sure, if your figures are too far off. He is pretty understanding.

If you can explain, he understands. He also can really help you out on a serious production problem. He can tell you what to do. He knows just how far a job should be run be- fore it should be pulled off.

In this organization, as these comments suggest, the knowl- edge and expertise of the top managers gained them respect from their subordinates and legitimated their strong influence over decisions. In the foods and plastics organizations the knowledge-based influence worked in a similar manner to justify the high influence of the middle managers centrally involved in helping to resolve interdepartmental conflict. Comments similar to those cited in earlier chapters may help to highlight this point. An integrator in the food organization explained the importance of expertise in his job:

Generally, the way I solve these problems is through man- to-man contact. I think face-to-face contact is the very best thing. Also, what we [the integrators] find is that most people develop a heavy respect for expertise, and this is what we turn to when we need to work out an issue with the fellows in other departments.

Similarly, a fundamental research scientist in the plastics organization indicated (as did many others in this organization) that he believed the members of the integrating unit to be competent, which helped them to achieve collaboration:

I believe we have a good setup in [the integrating unit]. They do an excellent job of bringing the industry problems back to somebody who can do something about them. They do an excellent job of taking the projects out and finding uses for them. In recent years I think it has been staffed with competent men.

In all three high-performing organizations, then, our data suggest a consistency in three factors that helped those primarily responsible for achieving integration to settle interdepartmental disputes. The managers who were assigned the responsibility for resolving conflict were at a level in the organization where they had the knowledge and information required to reach interdepartmental decisions and they were regarded as competent by their associates. Thus (1) positional influence, (2) influence based on competence, and (3) the actual knowledge and information required to make decisions all coincided. While there was this similarity, as we pointed out above, the level at which influence and knowledge were concentrated varied among the organizations because of differences in the certainty of their respective environments.

A second important similarity in these three organizations lay in the mode of behavior employed to resolve conflict. All three, as we have seen, relied heavily on open confrontation. The managers involved in settling conflicts were accustomed to open discussion of all related issues and to working through differences until they found what appeared to be an optimal solution. This was so regardless of the level at which the conflicts were handled. Typical comments from managers in each of the three organizations illustrate this point more vividly than the numerical data reported earlier. A researcher in the plastics organization described how he and his colleagues resolved conflicts:

I haven’t gotten into any disagreements yet where we let emotions stand in the way. We just go to the data and prove out which is right. If there is still some question about it, somebody can do the work to re-examine it. Emotions come up now and then. However, we usually have group decisions, so if I am not getting anywhere, I have to work it out with the others.

A production engineer in the food organization expressed a similar viewpoint:

We often will disagree as to basic equipment. When we can’t agree on what equipment to use, we will collaborate on some tests [with research], and sometimes we will run it both ways to find out what is the best way. Actually, the way this works out, one of their fellows and I will be at each other’s desk doing a lot of scratching with a pencil trying to figure out the best answer and to support our point of view. We will finally agree on what is the best way to go. It is a decision we reach together.

The director of research in the container organization discussed his role in the resolution of conflict with the chief executive:

I am sure a lot of people would say this is a one-man com-pany. Sure, [the chief executive] keeps close tabs on the dollars, and I must keep good score for him in regard to everything we spend. He is pretty gentle with me, and I have no run-ins with him. He talked to me this morning about a problem, and I knew that regardless of whether I said yes or disagreed with him he would have gone along and taken my advice. He likes to complain a lot, and holler and bellow and be like a wild bull, but he gives up when he sees a good case. He’ll ask for a real good story, and we have to give it to him, but if it is a good story, he will go along with us.

We should emphasize several important points about this comment. It and similar remarks from the major executives in the container organization indicated that while the chief executive was strong and dominant, he expected to have all points of view and pertinent information discussed before making a decision. These responses likewise indicated that there was give and take in these discussions and that the other major executives often influence the outcome, if the facts supported their point of view. It is also worth noting, as a comment from a plant manager in this organization suggests, that lower managers used the same method to resolve conflicts:

I’m an easy-going sort of fellow, but I get mad sometimes. When we get something to fight about, we just say it, face the problem, and it is over. We get the issue out on the table and solve it. It has to be done that way. [The production vice president] does it that way. We all follow his lead.

While these statements all deal with technical issues, we could cite similar comments concerning marketing problems. The important fact to emphasize is that these three organiza-tions relied on confrontation as a mode for resolving inter- departmental conflict to a greater extent than all but one of the other organizations (the low-performing food organization) . This fact does not seem unrelated to the importance of competence and knowledge as a basis of influence for the managers primarily responsible for resolving conflicts. High value was traditionally placed on knowledge and expertise in all three organizations. Consequently, managers were very willing to see disagreements settled on this basis.

This reliance on confrontation suggests another important characteristic of all three organizations: Managers must have had sufficient trust in their colleagues and, particularly in the case of the container organization, in their superiors to discuss openly their own points of view as they related to the issues at hand. They seemed to feel no great concern that expressing disagreement with someone else’s position (even a superior’s) would be damaging to their careers. This feeling of trust apparently fostered effective problem solving and decision making.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.