Regulative systems, normative systems, cultural-cognitive systems— each of these elements has been identified by one or another social theorist as the vital ingredient of institutions. The three elements form a continuum moving “from the conscious to the unconscious, from the legally enforced to the taken for granted” (Hoffman 1997: 36). One possible approach would be to view all of these facets as contributing, in interdependent and mutually reinforcing ways, to a powerful social framework—one that encapsulates and exhibits the celebrated strength and resilience of these structures. In such an integrated conception, institutions appear, as D’Andrade (1984: 98) observes, to be overdeter- mined systems: “overdetermined in the sense that social sanctions plus pressure for conformity, plus intrinsic direct reward, plus values, are all likely to act together to give a particular meaning system its directive force.”

While such an inclusive model has its strengths, it also masks important differences between the elements. The definition knits together three somewhat divergent conceptions that need to be differ- entiated. Rather than pursuing the development of a more integrated conception,1 I believe that more progress will be made at this juncture by distinguishing among the several component elements and identi- fying their different underlying assumptions, mechanisms and indica- tors.2 By employing a more analytical approach to these arguments, we can separate out the important foundational processes that transect the domain.

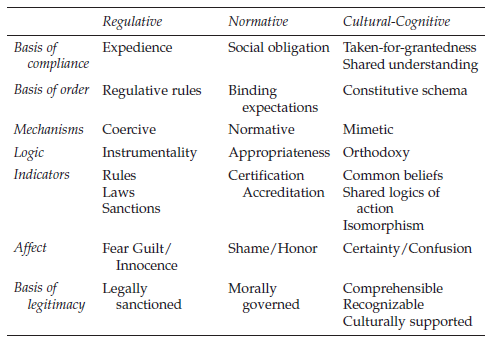

Consider Table 3.1. The columns contain the three elements—three pillars—identified as making up or supporting institutions. The rows define some of the principal dimensions along which assumptions vary and arguments arise among theorists emphasizing one or another element. This table will serve as a guide as we consider each element.

1. The Regulative Pillar

In the broadest sense, all scholars underscore the regulative aspects of institutions: Institutions constrain and regularize behavior. Scholars more specifically associated with the regulatory pillar are distin- guished by the prominence they give to explicit regulatory processes— rule-setting, monitoring, and sanctioning activities. In this conception, regulatory processes involve the capacity to establish rules, inspect others’ conformity to them, and, as necessary, manipulate sanctions— rewards or punishments—in an attempt to influence future behavior.

Table 3.1 Three Pillars of Institutions

Sanctioning processes may operate through diffuse, informal mecha- nisms, involving folkways such as shaming or shunning activities, or they may be highly formalized and assigned to specialized actors such as the police and courts. Political scientists examining international institutions point out that legalization—the formalization of rule systems—is a continuum whose values vary along three dimensions:

- obligation—the extent to which actors are bound to obey because their behavior is subject to scrutiny by external parties

- precision—the extent to which the rules unambiguously specify the required conduct

- delegation—the extent to which third parties have been granted authority to apply the rules and resolve disputes (Abbott, Keohane, Moravcsik, Slaughter, and Snidal 2001)

I suggest that regulatory systems are those that exhibit high values on each of these dimensions while normative systems, considered below, exhibit lower values on them.

Economists, including institutional economists, are particularly likely to view institutions as resting primarily on the regulatory pillar. A prominent institutional economist, Douglass North (1990), for example, features rule systems and enforcement mechanisms in his conceptualization:3

[Institutions] are perfectly analogous to the rules of the game in a competitive team sport. That is, they consist of formal written rules as well as typically unwritten codes of conduct that underlie and supplement formal rules… [T]he rules and informal codes are sometimes violated and punishment is enacted. Therefore, an essential part of the functioning of institutions is the costliness of ascertaining violations and the severity of punishment. (p. 4)

North’s emphasis on the more formalized control systems may stem in part from the character of the customary objects studied by economists and rational choice political scientists. They are likely to focus attention on the behavior of individuals and firms in markets or on other competitive situations, such as politics, where contending interests are more common and, hence, explicit rules and referees more necessary to preserve order. These economists and political scientists view individuals and organizations that construct rule systems or con- form to rules as pursuing their self-interests as behaving instrumen- tally and expediently. The primary mechanism of control involved, employing DiMaggio and Powell’s (1983) typology, is that of coercion.

Although the concept of regulation conjures up visions of repres- sion and constraint, many types of regulation enable and empower social actors and action, conferring licenses, special powers, and bene- fits to some types of actors. In general, regulatory processes within the private, market-based sector are more likely to rely on positive incen- tives (e.g., increased returns, profits); in their role vis-à-vis the private sector, public actors make greater use of negative sanctions (e.g., taxes, fines, incarceration). However, as we will see, public sector actors are capable of creating (constituting) social actors with broader, or more restricted, powers of acting.

Force, sanctions, and expedient responses are central ingredients of the regulatory pillar, but they are often tempered by the existence of rules that justify the use of force. When coercive power is both sup- ported and constrained by rules, we move into the realm of authority. Power is institutionalized (Dornbusch and Scott 1975: Ch. 2; Weber 1924/1968).

Much work in economics emphasizes the costs of overseeing sys- tems of regulation. Agency theory stresses the expense and difficulty entailed in accurately monitoring performances relevant to contracts, whether implicit or explicit, and in designing appropriate incentives (see Milgrom and Roberts 1992; Pratt and Zeckhauser 1985). Although in some situations agreements can be monitored and mutually enforced by the parties involved, in many circumstances it is necessary to vest the enforcement machinery in a third party expected to behave in a neutral fashion. Economic historians view this as an important func- tion of the state. Thus, North (1990) argues:

Because ultimately a third party must always involve the state as a source of coercion, a theory of institutions also inevitably involves an analysis of the political structure of a society and the degree to which that political structure provides a framework of effective enforcement. (p. 64)

However, North (1990: 54) also calls attention to problems that can arise because “enforcement is undertaken by agents whose own utility functions influence outcomes”—that is, third parties who are not neu- tral. This possibility is stressed by many historical institutionalists, such as Skocpol (1985), who argue that the state develops its own inter- ests and operates somewhat autonomously from other societal actors. In this and other ways, attention to the regulative aspects of institu- tions creates renewed interest in the role of the state: as rule maker, referee, and enforcer.

In an attempt to broaden the conception of law as a regulatory mechanism, law and society theorists insist that analysts should not conflate the coercive functions of law with its normative and cognitive dimensions. Rather than operating in an authoritative and exogenous manner, many laws are sufficiently controversial or ambiguous that they do not provide clear prescriptions for conduct. In such cases, law is better conceived as an occasion for sense-making and collective inter- pretation (Weick 1995), relying more on cognitive and normative than coercive elements for its effects (see Suchman and Edelman 1997; see also Chapter 6). In short, institutions supported by one pillar may, as time passes and circumstances change, be sustained by different pillars. The institutional logic underlying the regulative pillar is an instru- mental one: Individuals craft laws and rules that they believe will advance their interests, and individuals conform to laws and rules because they seek the attendant rewards or wish to avoid sanctions. Because of this logic, the regulative pillar is one around which rational choice scholars gather.

Empirical indicators of the development, extent, and province of regulatory institutions are to be found in evidence of the expansion of constitutions, laws, codes, rules, directives, regulations, and formal structures of control. For example, Tolbert and Zucker (1983) determine whether municipalities are mandated by state law to adopt civil service reforms, and Singh, Tucker, and House (1986) and Baum and Oliver (1992) ascertain whether voluntary service organizations are registered by oversight agencies. Dobbin and Sutton (1998) examine financial allocations to enforcement agencies as an indicator of regulatory enforcement.

As noted in Chapter 2, symbolic systems relate not only to sub- stance but also to affect; they stimulate not only interpretive but emo- tional reactions. D’Andrade (1984) has pointed out that meaning systems work in representational, constructive, and directive ways— providing cognitive guidance and direction—but also in evocative ways, creating feeling and emotions. Emotions are among the most important motivational elements in social life. Much recent research on brain activity and cognitive behavior stresses the interdependence of cognition and emotion. Long regarded as separate spheres related to distinctive parts of the brain, this dichotomization now appears grossly oversimplified and misleading (Dolan 2003; LeDoux 1996). Attention to emotion in social life by social scientists has largely been associated with ongoing work on identity (see Chapter 2) and on “institutional work” (Lawrence, Suddaby, and Leca 2009)—emphasizing the impor- tance of agency in maintaining and changing institutions (see Chapter 4). Contradictions between institutional demands at the macro level are experienced as conflicting role demands at the individual level—identity conflicts that need to be resolved (Creed, Dejordy, and Lok, 2010; Seo and Creed 2002). Emotions operate to motivate actors to change insti- tutions in which they have become disinvested or to defend institu- tions to which they are attached (Voronov and Vince 2012). Note that attention to the emotional dimensions of institutions privileges work at the micro (individual and interpersonal) levels of analysis.

Are their distinctive types of emotions engendered by encounters with the regulative organs of society? I think so and believe that the feelings induced may constitute an important component of the power of this element. To confront a system of rules backed by the machinery of enforcement is to experience, at one extreme, fear, dread, and guilt, or, at the other, relief, innocence and vindication. Powerful emotions indeed!

In sum, there is much to examine in understanding how regulative institutions function and how they interact with other institutional ele- ments. Through the work of agency and game theorists at one end of the spectrum and law and society theorists at the other, we are reminded that laws do not spring from the head of Zeus nor norms from the collective soul of a people; rules must be interpreted and dis- putes resolved; incentives and sanctions must be designed and will have unintended effects; surveillance mechanisms are required but are expensive and will prove to be fallible; and conformity is only one of many possible responses by those subject to regulative institutions.

A stable system of rules, whether formal or informal, backed by surveillance and sanctioning power affecting actors’ interests that is accompanied by feelings of guilt or innocence constitutes one prevail- ing view of institutions.

2. The Normative Pillar

A second group of theorists views institutions as resting primarily on a normative pillar (again, see Table 3.1). Emphasis here is placed on normative rules that introduce a prescriptive, evaluative, and obliga- tory dimension into social life. Normative systems include both values and norms. Values are conceptions of the preferred or the desirable together with the construction of standards to which existing struc- tures or behaviors can be compared and assessed. Norms specify how things should be done; they define legitimate means to pursue valued ends. Normative systems define goals or objectives (e.g., winning the game, making a profit) but also designate appropriate ways to pursue them (e.g., rules specifying how the game is to be played, conceptions of fair business practices) (Blake and Davis 1964).

Some values and norms are applicable to all members of the col- lectivity; others apply only to selected types of actors or positions. The latter give rise to roles: conceptions of appropriate goals and activities for particular individuals or specified social positions. These beliefs are not simply anticipations or predictions, but prescriptions— normative expectations—regarding how specified actors are sup- posed to behave. The expectations are held by other salient actors in the situation, and so are experienced by the focal actor as external pressures. Also, and to varying degrees, they become internalized by the actor. Roles can be formally constructed. For example, in an orga- nizational context particular positions are defined to carry specified rights and responsibilities and to have varying access to material resources. Roles can also emerge informally as, over time through interaction, differentiated expectations develop to guide behavior (Blau and Scott 1962/2003: Chs. 1, 4). Normative systems are typi- cally viewed as imposing constraints on social behavior, and so they do. But at the same time, they empower and enable social action. They confer rights as well as responsibilities, privileges as well as duties, licenses as well as mandates. In his essays on the professions, Hughes (1958) reminds us how much of the power and mystique associated with these types of roles comes from the license they are given to engage in forbidden or fateful activities—conducting intimate physical examinations or sentencing individuals to prison or to death. The normative conception of institutions was embraced by most early sociologists—from Durkheim and Cooley through Parsons and Selznick—perhaps because sociologists are more likely to examine those types of institutions, such as kinship groups, social classes, reli- gious systems, communities, and voluntary associations, where com- mon beliefs and values are more likely to exist. Moreover, it continues to guide and inform much contemporary work by sociologists and political scientists on organizations. For example, March and Olsen (1989) embrace a primarily normative conception of institutions:

The proposition that organizations follow rules, that much of the behavior in an organization is specified by standard operating procedures, is a common one in the bureaucratic and organiza- tional literature. It can be extended to the institutions of poli-tics. Much of the behavior we observe in political institutions reflects the routine way in which people do what they are sup- posed to do. (p. 21)

Although March and Olsen’s (1989) conception of rules is quite broad, including cultural-cognitive as well as normative elements—“routines, procedures, conventions, roles, strategies, organizational forms, and tech- nologies beliefs, paradigms, codes, cultures, and knowledge” (p. 22)—their focus stresses the centrality of social obligations:

To describe behavior as driven by rules is to see action as a match- ing of a situation to the demands of a position. Rules define rela- tionships among roles in terms of what an incumbent of one role owes to incumbents of other roles. (p. 23)

In short, scholars associated with the normative pillar stress the importance of a logic of “appropriateness” vs. a logic of “instrumental- ity.” The central imperative confronting actors is not “What choice is in my own best interests?” but rather, “Given this situation, and my role within it, what is the appropriate behavior for me to carry out?”

Empirical indicators of the existence and pervasiveness of norma- tive institutions include accreditations and certifications by standard setting bodies such as professional associations (Casile and Davis- Blake, 2002; Ruef and Scott 1998).

As with regulative systems, confronting normative systems can also evoke strong feelings, but these are somewhat different from those that accompany the violation of rules and laws. Feelings associated with the trespassing of norms include principally a sense of shame or disgrace, or for those who exhibit exemplary behavior, feelings of respect and honor. The conformity to or violation of norms typically involves a large measure of self-evaluation: heightened remorse or effects on self-respect. Such emotions provide powerful inducements to comply with prevailing norms.

Theorists embracing a normative conception of institutions empha- size the stabilizing influence of social beliefs and norms that are both internalized and imposed by others. For early normative theorists such as Parsons, shared norms and values were regarded as the basis of a stable social order. And as Stinchcombe (1997) has eloquently reaf- firmed, institutions are widely viewed as having moral roots:

The guts of institutions is that somebody somewhere really cares to hold an organization to the standards and is often paid to do that. Sometimes that somebody is inside the organization, maintaining its competence. Sometimes it is an accrediting body, sending out volunteers to see if there is really any algebra in the algebra course. And sometimes that somebody, or his or her commitment is lacking, in which case the center cannot hold, and mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. (p. 18)

Heclo (2008) also embraces a similar stance. Assuming what he terms an “inside-out” perspective on institutions—that is, viewing institutions from the standpoint of those participating in them—he affirms Selznick’s (1957: 101) distinction “between strictly instrumental attachments needed to get a particular job done and the deeper com- mitments that express one’s enduring loyalty to the purpose or pur- poses that lie behind doing the job in the first place.” Heclo insists:

Deeper than the agent/principal issues is the agent/principle perspective. It presupposes that as beings (which by existing we surely are) we humans are moral agents. That is to say, by virtue of being human, we experience our existence as partaking in questions of right and wrong. To say human life is to say morally- implicated life. (p. 79)

3. The Cultural-Cognitive Pillar

A third set of institutionalists, principally anthropologists like Geertz and Douglas and sociologists like Berger, DiMaggio, Goffman, Meyer, Powell, and Scott stress the centrality of cultural-cognitive ele- ments of institutions: the shared conceptions that constitute the nature of social reality and create the frames through which meaning is made (again, see Table 3.1). Attention to the cultural-cognitive dimension of institutions is the major distinguishing feature of neoinstitutionalism within sociology and organizational studies.

These institutionalists take seriously the cognitive dimensions of human existence: Mediating between the external world of stimuli and the response of the individual organism is a collection of internal- ized symbolic representations of the world. “In the cognitive para- digm, what a creature does is, in large part, a function of the creature’s internal representation of its environment” (D’Andrade 1984: 88). Symbols—words, signs, gestures—have their effect by shaping the meanings we attribute to objects and activities. Meanings arise in interaction and are maintained and transformed as they are employed to make sense of the ongoing stream of happenings. Emphasizing the importance of symbols and meanings returns us to Max Weber’s cen- tral premise. As noted in Chapter 1, Weber regarded action as social to the extent that the actor attaches meaning to the behavior. To under- stand or explain any action, the analyst must take into account not only the objective conditions but the actor’s subjective interpretation of them. Extensive research by psychologists over the past three decades has shown that cognitive frames enter into the full range of information-processing activities, from determining what information will receive attention, how it will be in encoded, how it will be retained, retrieved, and organized into memory, to how it will be inter- preted, thus affecting evaluations, judgments, predictions, and infer- ences. (For reviews, see Fiol 2002; Markus and Zajonc 1985; Mindl, Stubbart, and Porac 1996.)

As discussed in Chapter 2, the new cultural perspective focuses on the semiotic facets of culture, treating them not simply as subjective beliefs but also as symbolic systems viewed as objective and external to individual actors. Berger and Kellner (1981: 31) summarize: “Every human institution is, as it were, a sedimentation of meanings or, to vary the image, a crystallization of meanings in objective form.” Our use of the hyphenated label cognitive-cultural emphasizes that internal interpretive processes are shaped by external cultural frameworks. As Douglas (1982: 12) proposes, we should “treat cultural categories as the cognitive containers in which social interests are defined and classified, argued, negotiated, and fought out.” Or in Hofstede’s (1991: 4) graphic metaphor, culture provides patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting: mental programs, or the “software of the mind.”4

The stress in much of this work on cognition and interpretation points to important functions of the cultural-cognitive pillar but over- looks a dimension that is even more fundamental: its constitutive func- tion. Symbolic processes, at their most basic level, work to construct social reality, to define the nature and properties of social actors and social actions. We postpone consideration of this function until the fol- lowing section of this chapter, however, because it raises questions regarding the fundamental assumptions underlying social science research.

Cultural systems operate at multiple levels, from the shared defini- tion of local situations, to the common frames and patterns of belief that comprise an organization’s culture, to the organizing logics that structure organization fields, to the shared assumptions and ideologies that define preferred political and economic systems at national and transnational levels. These levels are not sealed but nested, so that broad cultural frameworks penetrate and shape individual beliefs on the one hand, and individual constructs can work to reconfigure far- flung belief systems on the other.

Of course, cultural elements vary in their degree of institutional- ization—the extent of their linkage to other elements, the degree to which they are embodied in routines or organizing schema. When we talk about cognitive-cultural elements of institutions, we are calling attention to these more embedded cultural forms: “culture congealed in forms that require less by way of maintenance, ritual reinforcement, and symbolic elaboration than the softer (or more ‘living’) realms we usually think of as cultural” (Jepperson and Swidler 1994: 363).

Cultures are often conceived as unitary systems, internally con- sistent across groups and situations. But cultural conceptions fre- quently vary: Beliefs are held by some but not by others. Persons in the same situation can perceive the situation quite differently—in terms of both what is and what ought to be. Cultural beliefs vary and are frequently contested, particularly in times of social disorganiza- tion and change (see DiMaggio 1997; Martin 1992; 2002; Seo and Creed 2002; Swidler 1986).

For cultural-cognitive theorists, compliance occurs in many cir- cumstances because other types of behavior are inconceivable; routines are followed because they are taken for granted as “the way we do these things.” The prevailing logic employed to justify conformity is that of orthodoxy, the perceived correctness and soundness of the ideas underlying action.

Social roles are given a somewhat different interpretation by cul- tural than by normative theorists. Rather than stressing the force of mutually reinforcing obligations, cultural-cognitive theorists point to the power of templates for particular types of actors and scripts for action (Shank and Abelson 1977). For Berger and Luckmann (1967), roles arise as common understandings develop that particular actions are associated with particular actors:5

We can properly begin to speak of roles when this kind of typifica- tion occurs in the context of an objectified stock of knowledge common to a collectivity of actors… Institutions are embodied in individual experience by means of roles… The institution, with its assemblage of “programmed” actions, is like the unwritten libretto of a drama. The realization of the drama depends upon the reiterated performance of its prescribed roles by living actors. . . . Neither drama nor institution exist empirically apart from this recurrent realization. (pp. 73–75)

Differentiated roles can and do develop in localized contexts as repetitive patterns of action gradually become habitualized and objec- tified, but it is also important to recognize the operation of wider insti- tutional frameworks that provide prefabricated organizing models and scripts (see Goffman 1974; 1983). Meyer and Rowan (1977) and DiMaggio and Powell (1983) emphasize the extent to which wider belief systems and cultural frames are imposed on or adopted by indi- vidual actors and organizations.

Much progress has been made in recent years in developing indica- tors of cultural-cognitive elements. For many years, investigators such as social anthropologists and ethnomethodologists relied on close, long-term observation of ongoing behavior from which they inferred underlying beliefs and assumptions (e.g., Turner 1974). Later, quantita- tive researchers employed survey methodologies to uncover shared attitudes and common values (e.g., Hofstede 1984). More recently, however, a “new archival research” approach has emerged in which scholars employ formal analytical methodologies such as content, semiotic, sequence, and network analysis to probe materials such as discourse in professional journals, trade publications, organizational documents, directories, annual reports, and specialized or mainstream media accounts. This type of research has flourished due to the wide- spread availability of computer-analyzable documents. The best of this work illuminates “relevant features of shared understandings, profes- sional ideologies, cognitive frames or sets of collective meanings that condition how organizational actors interpret and respond to the world around them” (Ventresca and Mohr 2002: 819).

The affective dimension of this pillar is expressed in feelings from the positive affect of certitude and confidence on the one hand versus the negative feelings of confusion or disorientation on the other. Actors who align themselves with prevailing cultural beliefs are likely to feel competent and connected; those who are at odds are regarded as, at best, “clueless” or, at worst, “crazy.”

A cultural-cognitive conception of institutions stresses the central role played by the socially mediated construction of a common frame- work of meanings.

4. A Fourth Pillar? Habitual Dispositions

In a thoughtful essay, Gronow (2008) has proposed a fourth ele- ment, which he argues constitutes yet another basis for institutions. Building on the work of the American pragmatists, including Dewey, James, and others who influenced the work of early economic theorists Veblen and Commons (see Chapter 1), Gronow suggests that we add habitual actions to our framework. He suggests that “habitual disposi- tions are related to actions that have been repeated in stable contexts and therefore require only a minimal amount of conscious thought to initiate and implement” (p. 362). Although habits can be relatively automatic, Gronow points out that pragmatists insisted habits are not mere dead routines, but can include and overlap with reason and con- scious choice.

While I welcome the strengthening of connections between prag- matism and institutional arguments and agree that more attention needs to be given to activities and practices, habits and routines, I am not persuaded of the need to add a fourth pillar to the conceptual framework. Shared dispositions are fundamentally cultural-cognitive elements closely tied to repetitive behavior. Like other such elements, they can be only semiconscious and taken for granted by the actors. Moreover, I take into account the important role of activities and rou- tines by treating them as of one of the major carriers of institutional elements (see Chapter 4).

5. Combinations of Elements

Having introduced the three basic elements and emphasized their distinctive features and modes of working, it is important to restate the truth that in most empirically observed institutional forms, we observe not one, single element at work but varying combinations of elements. In stable social systems, we observe practices that persist and are reinforced because they are taken for granted, normatively endorsed, and backed by authorized powers. When the pillars are aligned, the strength of their combined forces can be formidable.

In some situations, however, one or another pillar will operate virtually alone in supporting the social order; and in many situations, a given pillar will assume primacy.

Equally important, the pillars may be misaligned: They may sup- port and motivate differing choices and behaviors. As Strang and Sine (2002: 499) point out, “Where cognitive, normative, and regulative sup- ports are not well aligned, they provide resources that different actors can employ for different ends.” Such situations exhibit both confusion and conflict, and provide conditions that are highly likely to give rise to institutional change (Dacin, Goodstein, and Scott 2002; Kraatz and Block 2008). These arguments are pursued, illustrated, and empirically tested in subsequent chapters.

Source: Scott Richard (2013), Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, SAGE Publications, Inc; Fourth edition.