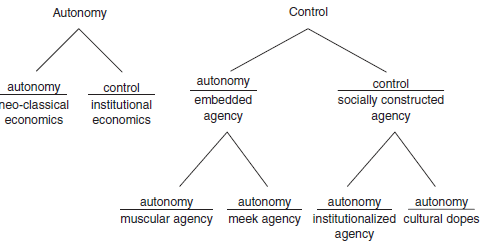

Andrew Abbott (2001) has pointed out that all academic disciplines become more complex over time, obviously differentiating among more specialized areas of study (e.g., the sociology of the family, the sociology of religion), but also, less obviously, by creating fractals. In this process, distinctions are created by the development of dichotomies (e.g., autonomy vs. control), but then the distinction is reproduced at a lower level, and again at a lower level, in a process of iteration. This process harkens back, as Abbott observed, at least to the work of Kant in the 19th century, but can be observed today in the development of institutional theory (see Figure 9.1).

In the dichotomy, autonomy–control, institutional theory clearly resides on the control side. It emphasizes the sources and uses of stability and order. However, as I have documented, as the field developed, we observe the dichotomy repeat itself, as some scholars begin to empha- size the existence and utility of autonomy within institutional frame- works (e.g., “embedded agency”) (Battilana and D’Aunno 2009) in opposition to those scholars, such as Meyer (2008), who continue to stress the extent to which agency and actors are “socially constructed” by institutional processes. As this dialogue has continued, disputes have begun to break out among those who focus on autonomy within institutions as to how much or how little agency is involved, or, in a parallel fashion among scholars emphasizing control within institu- tions, how much or how little control is possible (Powell and Colyvas 2008), and so on. The distinctions become ever more fine.

Figure 9.1 Theory Development as Fractal Creation

This fractal mode of differentiation has several effects, as Abbott points out. First, scholars pay more attention to others in nearby rather than more distant camps. Thus, over time scholars tend to become more provincial, fine-tuning distinctions to separate themselves from close neighbors and distancing themselves from those working in related but more remote areas. Moreover, arguments between scholars can cause misunderstandings because the distinctions made are rela- tional rather than linear ones.

The use of this approach also creates a now-familiar pattern of (re) discovery when, after burrowing deeper and deeper into territory defined by pursuing an ever-subdividing distinction, we are confronted with important factors we have bracketed out and are compelled to “bring something-or-other back in.” And the things brought back in have included both sides of most of the important social scientific dichotomies. Some writers have brought people back in, others behav- ior. Some have brought social structure back in, others culture. Some have brought ourselves, others the context. Some processes, others structures. Some capitalists, others workers. Some firms, others unions. A glance at these articles makes one think that sociology and indeed social science more generally consists mainly of rediscovering the wheel. A generation triumphs over its elders, then calmly resurrects their ideas, pretending all the while to advance the cause of knowl- edge. Revolutionaries defeat reactionaries; each generation plays first the one role, then the other (Abbott 2001: 16–17).

Finally, this pattern produces both change and stability. “Any given group is always splitting up over some fractal distinction. But dominance by one pole of the distinction requires that pole to carry on the analytic work of the other” (Abbott 2001: 21). In short, this pattern of theorizing produces steady work for social scientists, but not neces- sarily scientific progress.

Source: Scott Richard (2013), Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, SAGE Publications, Inc; Fourth edition.