Even if the company is good at using the New 7-S’s, competitors can still seize the initiative, as indicated by the above discussion of the four arenas. Competitors have taken advantage of vulnerabilities of Intel in each of the arenas. They have also used their own strengths in certain S’s or changed the way the S’s are used.

If a company is concentrating on only a few S’s, competitors often shift the competition to other S’s that are not the current focus of competition. For example, if a company is focusing primarily on increasing speed (S-3), its competitor could seize the initiative by focusing on customer service (S-l).

Even if a company such as Intel is using all the New 7-S’s, competitors still have the opportunity to shift the way some or all of the New 7-S’s are used. Because the company’s skill in using the New 7-S’s is relative to the skill of its competitors, a company that is good at using them against one competitor may be less skillful against a new competitor. For example, Ford was relatively strong in achieving superior stakeholder satisfaction (S-l) when competing for customers against only GM and Chrysler, but it fell behind when Honda and Toyota came along and raised the stakes.

Because skill in the New 7-S’s is relative and competitors create shifts in emphasis among the various S’s, the use of the New 7-S’s is a dynamic process. This dynamic view is the focus of the second analytical tool presented here, Dynamic 7-S analysis. In addition to the competitor analysis described above, the New 7-S’s are useful for evaluating the stages of evolution of an industry to identify future opportunities. As indicated by the two examples below—in cameras and watches—this dynamic process often leads to a pendulum swing in how the New 7-S’s are used.

Companies that recognize this swing can take advantage of opportunities to push the industry in the opposite direction from the one in which it is traveling. Companies that do not understand these dynamic swings concentrate on sustaining their current advantage and keeping the pendulum moving in the same direction. They ride high during the swing of the pendulum that favors them. Then they are shocked by a sudden reversal of fortune as the pendulum swings in the opposite direction. The hyper- competitive firm, on the other hand, anticipates these shifts in direction and actually works to encourage and take advantage of them.

Consider two examples of how this dynamic analysis is applied to the camera and watch industries.

1. Dynamic 7-S Analysis of the Camera Industry

ROUND ONE: KODAK VS. POLAROID

The first stage of competition was between Polaroid and Kodak over in- stamatic cameras. Kodak invented the market for amateur photography as the world’s first integrated photographic firm. Because it controlled both film manufacturing and development, it had a lock on the U.S. market that could not be shaken by either foreign or domestic competitors. Kodak kept one step ahead of competitors in film quality, using inexpensive cameras as a way to sell more film and using the New 7-S’s to its advantage over Polaroid (see Figure 9-1).

Polaroid’s development of instant photography gave it an advantage in technological know-how that allowed it to grow by an average annual compounded rate of 25 percent from 1947 to 1979.12 It continued to fuel its growth by extending its basic innovation of instant photography with enhancements such as instant color photography and the SX-70 system. Still, Kodak controlled an estimated 85 percent of the camera market in 1976.13

In 1976 Kodak declared war on Polaroid. It announced that it would introduce its own instant camera. The two companies competed head-to- head on instant photography. But the greatest gains were made in twenty- four-hour film processing, which eroded the advantage of instant photography. Despite losing its right to make and sell instant cameras in a court battle with Polaroid, Kodak’s superior film quality and increased ease of snapping a good photo captured many more amateurs than instant film. So Kodak won the battle against Polaroid for market share.

As a sidelight Polaroid moved into the motion picture business. In 1977 Polaroid introduced its instant motion picture camera to compete with Kodak’s Super-8 movie cameras. The Polavision system produced a film that could be viewed two minutes after it was shot. Its drawbacks were that it did not have sound and was limited to two minutes and forty seconds. Polaroid dropped the product in 1980, after it was run over by advancing videotape technology that offered instant films with greater length and sound.

FIGURE 9-1

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS: KODAK VERSUS POLAROID

ROUND TWO: CANON VS. KODAK

Kodak’s relative strengths against Polaroid were not strong enough to hold out against Japanese competitors. Kodak was successfully attacked by Canon and other companies in the growing 35 mm autofocus market. Canon used the New 7″S’s to create advantage over Kodak (see Figure 9-2). The 35 mm camera was once used only by the most sophisticated amateur photographers. But Japanese R&D investments created advances in technology that made the 35 mm camera as convenient to use as Kodak’s instamatics, giving amateurs the advantage of highenquality 35 mm film. Prices of these cameras also came down to the amateur’s range. Kodak tried to defend its instamatic product by offering more processing. More competitors, such as Minolta and Olympus, entered the 35 mm mar- ket. By 1989, in the first few years after their introduction, these “point and shoot” cameras captured nearly 40 percent of the world camera market,14 and by the early 1980s 35 mm had grown to more than 50 percent of the amateur market,15 Kodak attempted to change the rules of the game by entering the disk market, but this has turned out to be rather unsuccessful to date.

FIGURE 9-2

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS: CANON VERSUS KODAK

Kodak lost this round of competition as Canon and others seized the initiative with 35 mm cameras. Kodak continued to retain the instamatic market and dominated film manufacturing and production. But a big chunk of the camera market was carved out by the 35 mm camera companies.

ROUND THREE: SONY VS. KODAK

The next level of competition is focusing on digital photography—images that can be stored on magnetic disks or CDs and edited on personal computers. Here Sony used the New 7-S’s (see Figure 9-3) and seized the initiative early on, but the battle for this new market is still far from over. In the fall of 1981, Sony announced the Mavica, an all-electronic camera for recording still pictures on a magnetic disk. The images could be viewed instantly on a television. The initial price was $650 for the camera, $220 for the playback unit, and approximately $1,000 for a printer. This was far above the price of a standard film-based camera, even with the savings on film developing. The quality of the image on a television screen was much lower than that of a print, but Sony knew that high-definition television eventually would dramatically alter the quality of the image to make it competitive with that of 35 mm or instant photography.16

In response to the digital-camera threat, Kodak implemented a $1 billion push into digital images in the late 1980s and 1990s but ultimately decided to aggressively market only a $400 digital storage system. The Photo CD stores up to one hundred 35 mm film negatives on a compact disc. Customers still use traditional film and receive prints, but they can also have the prints transferred to a CD that can play on their televisions. This allows Kodak to continue to benefit from its current advantages in film, paper, and chemicals while beginning to build a market for digital images. But has the company, as a 1993 article in Business Week suggests, “decided that boosting today’s bottom line is more important than a distant threat” from digital photography?17 Has it tried to shore up its current advantages at the expense of aggressively pursuing future advantages in this emerging market?

Although its major push is the Photo CD, Kodak, along with Sony and other competitors, has continued to develop capabilities and launch digital photography products. Kodak’s DCS 200, priced at between $8,500 and $10,000, is attached to a Nikon camera body and provides high- resolution digital images.18 Sony has also continued to upgrade its Mavica to create the ProMavica MVC-7000, priced at about $7,500 and up.19 The high prices and sophistication of these cameras limit the market, but they could be the forerunners of a large future market for amateur digital equipment. Although Sony was first out of the box with the Mavica and initially may have seized the advantage, the ultimate winner in this contest is still far from certain.

In sum, this dynamic analysis of the New 7-S’s shows how each of them shifts over time. At one moment Kodak had the advantage by doing each of the New 7-S’s well. Then, despite doing the 7-S’s well, Kodak lost its advantage to 35 mm’s and, perhaps, the electronic cameras of the future to competitors, using the New 7S’s to destroy the advantage created by Kodak.

FIGURE 9-3

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS: SONY VERSUS KODAK

This analysis illustrates what must be done by Kodak to survive in the future against the 35 mm and electronic cameras. To reseize the initiative, Kodak will have to do each of the New 7-S’s better than their competitors, disrupting the market by finding ways to serve customers better than (or in new ways compared to) the electronic and 35 mm cameras have done. Kodak’s disposable camera (made from cardboard) is one example of how Kodak is reseizing the initiative.

2. Dynamic 7-S Analysis of the Watch Industry

The Swiss had gained and sustained the initiative in the watch industry through a commitment to high-quality watches. In 1969 one of every two watches was Swiss-made, almost all of them with mechanical movements.20 Until the 1970s, perhaps the most significant technological innovation was the hairspring in 1675. In the early 1970s Swiss watchmakers took a one-two punch from two innovations—quartz watches and digital electronic watches—that transformed the industry.

ROUND ONE: SEIKO (QUARTZ) VS. SWISS WATCHMAKERS

Many of the leading Swiss watchmakers were so busy trying to sustain their existing advantage in mechanical watches that they did not move on to the next temporary advantage in the market. They lost the initiative in these new markets and their dominant position in watchmaking to Japanese and U.S. competitors, allowing these competitors to seize the opportunity to gain dominant positions in the market. Swiss watchmakers later regained the initiative by moving watches into the fashion industry with Swatch watches.

The quartz watch shifted the rules of competition. Seiko introduced the electronic quartz watch in 1969, and only one major Swiss watchmaker, Longines-Wittnauer, followed closely with its own watch. By using the New 7-S’s, Japanese manufacturers such as Seiko (see Figure 9-4) and Casio seized this opportunity in the timing and know-how arena, shifting the rules of competition from mechanical watches to quartz watches. Their aggressive move into the medium-priced market gave Japanese manufacturers 35 percent of world sales in the medium-priced market by the beginning of the 1980s and cost the Swiss industry forty-five thousand jobs.21 Quartz watches won dominance in the market. By 1988 five of every six timepieces produced worldwide were quartz watches.22

FIGURE 9-4

DYNAMIC 7’S ANALYSIS: SEIKO VERSUS SWISS WATCHMAKERS

ROUND TWO: PULSAR (DIGITAL) WATCHES VS. THE SWISS WATCHMAKERS

Then came solid-state digitals. In 1970 U.S watchmaker Hamilton Watch Company unveiled a solid-state electronic watch with digital readouts, under the brand name Pulsar. Its first digital watch went on sale in 1972 for $2,100 with a red LED display. LEDs were later replaced by LCDs, and growth of the digital market continued. Pulsar used the New 7-S’s to seize the initiative from the Swiss watchmakers (see Figure 9-5). Sales of the space-age watches continued to climb through the 1970s and by the end of the 1970s, nearly one in four watches sold worldwide was a digital.23

Then the initiative shifted again. An influx of inexpensive digital watches from hundreds of manufacturers in Hong Kong made the city the world’s largest-volume exporter of watches, with nearly 50 million watches by 1978. It led to what the president of the Hong Kong Watch Manufacturers Association called a time of “vicious competition.”24 This influx of inexpensive watches also killed sales of high-end digitals. Hamilton sold its Pulsar operations. Digitals dropped into the low-end of the watch market, with multifunctional watches, clocks on pens, and calculators.

FIGURE 9-5

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS:

PULSAR (DIGITAL WATCHES) VERSUS SWISS WATCHMAKERS

Digitals also had sacrificed fashion and design for high-tech image. This opened up opportunities that the Swiss were now positioned to use to seize the initiative to shift competition back to quartz analogs (traditional faces with quartz works).

ROUND THREE: SWATCH (SWISS) VS. TIMEX

In 1983 it was the Swiss watchmakers’ turn to use the New 7-S’s (see Figure 9-6). They seized the initiative in the medium-priced market through Swatch watches. Swatch, created by the Société Suisse de Micro- électronique et d’Horlogerie (SMH), recognized that watches are a combination of timepieces and fashion accessories—and emphasized the latter. When these inexpensive ($35—$75) watches, using plastic and mechanized production, were introduced, they were derided by some as the last gasp of the Swiss watchmaking industry. They were a far cry from the meticulously crafted timepieces for which the Swiss were famous. But they were a great success.

FIGURE 9-6

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS: SWATCH VERSUS TIMEX

By shifting the emphasis from the quality of the timepiece to the innovation of the design, Swatch was able to seize a large share of the medium- priced and low-end watch market. It made design innovation the central focus of watchmaking—with such models as the transparent Swatch, fruit- scented Swatch, and oversized “pop” Swatches on elastic bands. Sales of Swatch watches broke all records as the largest and fastest-selling timepiece, with annual sales topping seventeen million units in 1991.25 Even though some designs have failed, the sheer pace of product and design innovation has assured steady growth of the Swatch market. Swatch’s ability to quickly and cheaply roll out new varieties of watches was gained through a process innovation that cut the number of parts in the watches and through fully automated assembly. SMH carried this emphasis on innovation into its higher-end Omega watches and RockWatches (in a granite case).

Swatch is now applying the same principle of fashion and variety to such industries as telephones, pagers, fax machines, and automobiles (in a joint venture with Volkswagen). The car, which will be powered by an electric or electric-gasoline motor, rethinks automobile design in the same way Swatch shifted the rules of watchmaking.

u.s. watchmaker Timex has pursued a slow and steady strategy that mimics its “Takes a Licking but Keeps on Ticking slogan. It took a licking from Swatch. It has rapidly followed trends in the watch industry, includ’ ing the development of quartz and digital watches. It held a strong position in the low-end of the market until it was blindsided by the success of Swatch watches. Timex was cut out of many department stores during the rise of design and status in the 1980s. Timex had to develop new capabilities in design flexibility and product diversity, setting up professional design studios in France and the United States. But it never abandoned its emphasis on low-priced reliability. It has moved most of its production overseas to take advantage of lower labor costs.

ROUND FOUR: THE SHIFT BACK TO VALUE

An emerging shift in consumer taste from fashion back to value (Timex’s strength) may shift the rules back into Timex’s favor. Through its competition with Swatch, Timex has built new capabilities in design and product innovation. By playing against this weakness in Timex, Swatch has helped Timex develop it into a strength. This, coupled with its traditional image of reliability and value, have made it a strong competitor in the valueconscious 1990s.

As an indication of its reviving fortunes, Timex was welcomed back to Bloomingdale’s and other department stores in 1989. Its innovative ring watch became Bloomingdale’s hottest-selling item in that year.26 Although a shift in demographics has aided Timex in the short run, its longterm success may rest on its own ability to identify the next temporary advantage and seize the initiative in the market. If it doesn’t, its slow-and- steady strategy may be undermined by a more aggressive competitor (the next Swatch).

Swatch’s diverse strengths put it in a strong position to seize the initiative again, but its weakness is that it could be blinded by success and fail to identify and create the next temporary advantage in the industry. Its emphasis on product variety has already lost some of its steam in the valueconscious nineties, but its capabilities for speed and surprise could be deployed in other ways than creating design variety.

ROLEX: EXCEPTION OR THE NEXT VICTIM OF HYPERCOMPETITION?

At the extreme other end of the market, Rolex has sustained what is an apparently stable advantage with its high-priced, limited-edition watches. After establishing a reputation with such innovations as automatic winding and the oyster casing, Rolex watches have changed very little since 1933. But the company has significantly improved its production technology.27 The Swiss-based company makes about 500,000 watches per year, far less than the demand. Rolex has continued to emphasize its exclusive image, through famous Rolex wearers such as Ian Fleming’s James Bond character and real-life heros such as politicians and athletes.

Rolex has found a way to survive in hypercompetition without being hypercompetitive by staking out the luxury portion of the market. To do so, Rolex has used some of the New 7-S’s to create its image and position (see Figure 9-7). Its sales have climbed by 20 percent annually over the past twenty-five years.28 It has circumscribed its own market by offering a limited-edition item. This may have limited growth, but it sustains a strong demand. But Rolex has also begun to face increasing competition at the high end of the market from a variety of Japanese and Swiss competitors, some of whom have entered at the middle of the market and moved up.

Rolex, with little speed or surprise, is vulnerable to attack by an aggressive competitor. In the same way that BMW and Mercedes were successfully attacked by Lexus, Infiniti, and Acura, Rolex’s high-end market could be eroded by companies that can offer equal or superior value for a lower price. A competitor could also shift the rules of competition in the high end to turn Rolex’s investments in its current advantage against it. Perhaps the lower ends of the market offer more opportunities as watch sales have grown worldwide, but if this growth tapers off, competitors may be more interested in putting resources into attacking the entrenched high-end position of Rolex.

FIGURE 9-7

DYNAMIC 7-S ANALYSIS: ROLEX’S VULNERABILITY TO FUTURE MOVES

The watch industry illustrates the dynamic nature of the New 7-S’s, with firms seizing the initiative by improving their use of each of the New 7-S’s compared to the historical patterns of competitors. This industry (especially Rolex) also points out the vulnerabilities created by failing to use the New 7-S’s while attempting to sustain old advantages.

2. Reversals of Fortune: Pendulum Swings in the Use of the New 7’S’s

As discussed above, industries go through a dynamic evolution in which competitors who are skilled at using the New 7-S’s find themselves at a sudden disadvantage. Kodak was dominant in the use of the New 7-S’s in its competition with Polaroid, but when Canon came, Kodak’s fortunes were reversed.

Overall, the analysis of many industries reveals similar patterns of reversals. Often these reversals develop into a pendulum swing in which the industry moves back and forth between two or more key competitive factors.

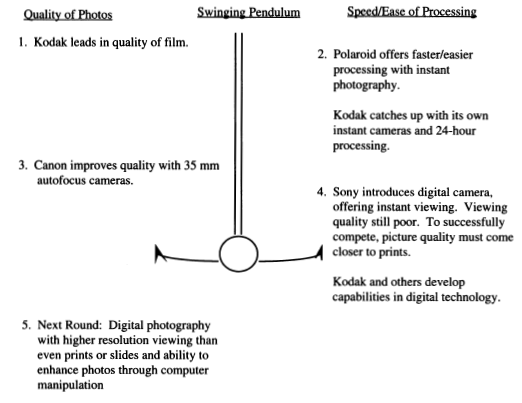

In the camera industry the pendulum swings between photo quality and speed and ease of processing (see Figure 9-8). Kodak dominated in quality and speed of processing until Polaroid offered much faster and easier film processing. Kodak temporarily won the first round by offering its own instant photography and through the advent of twenty-four-hour processing services. Next, the focus shifted back to photo quality. Canon’s introduction of the 35 mm autofocus camera offered a higher level of film quality. The emerging digital photography field again shifted the competition back to speed and ease of processing by allowing photographers to view photos instantly on their televisions. Sony’s Mavica camera offered this ease of processing at a significant sacrifice in photo quality. The next key factor in this competition appears to be the increase in resolution quality of digital photos. This increased resolution will allow Sony and others to gain the lead in quality again. Speed and ease of processing may someday become the next swing of the pendulum, but it is unclear when and how this will occur.

FIGURE 9-8

REVERSALS OF FORTUNE IN THE CAMERA INDUSTRY

Similarly, the watch industry has shifted back and forth between accuracy and fashion. The Swiss mechanical watch established the highest standards of accuracy until the quartz watch successfully challenged it. Seiko and other leaders in quartz watchmaking won that round. Digital watches, which also used quartz crystals, challenged the Swiss watches on fashion as it became fashionable to wear the high-tech watches. As interest in high-tech fashion was replaced by flair, Swatch capitalized on this new trend. Swatch used it to attack Timex and other companies that had few skills in leading-edge fashion design. The next dramatic shift might be another breakthrough in accuracy. In the meantime companies continue to compete on changing fashion trends.

This swinging pendulum and reversal of fortunes usually catch companies unprepared. Swiss watchmakers were riding high while the pendulum was swinging in the direction of mechanical watches. They stumbled badly when it shifted to quartz. Their quartz competitors were unprepared for the success of Swatch, and the fortunes of the Swiss reversed again.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.