As discussed in Part II, approaches to long-term strategic planning that are designed to sustain advantage actually are a poor preparation for long-term success. At best, they prepare companies to win one round of competition. Traditional five-year and ten-year planning models that emphasize sustained advantage and planned sequences of milestones and budgets are usually too inflexible to meet the dynamic challenges facing companies in hypercompetitive environments. They play out one scenario for the future rather than allow the company to develop a dynamic and flexible strategy to meet or even create several possible scenarios.

1. A Three-Level Dynamic Strategic Planning Model

Using the New 7-S’s

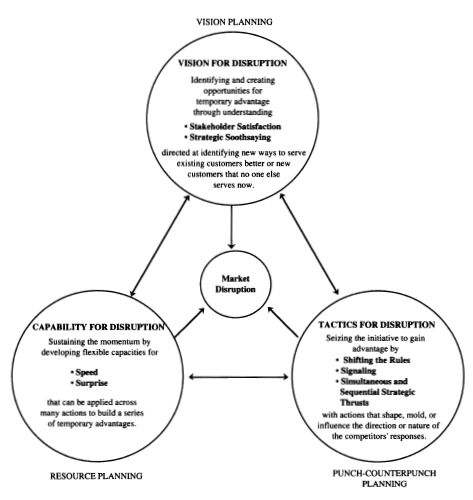

In contrast, the New 7-S’s offer an approach to strategic planning that is more flexible and dynamic. The three groupings of the New 7-S’s described in the preceding chapter are used to consider three levels of a new form of planning:

- Planning a vision for disruption:

S-1 Superior stakeholder satisfaction

S-2 Strategic soothsaying

- Resource planning (building capabilities):

S-3 Capabilities for speed

S-4 Capabilities for surprise

- Tactics: Punch-Counterpunch Planning:

S-5 Shifting the rules of competition

S-6 Signaling

S-7 Simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts

As indicated by Figure 9-9, this strategy development is not a linear process. Traditional long-range planning usually moves from developing a vision to building resources to carry out that vision to developing specific plans for actions. This new dynamic planning model engages in these three steps simultaneously and continuously. The vision is constantly being sharpened. Capabilities for speed and surprise are constantly being developed, and a series of tactics is selected, adjusted, and readjusted to meet emerging opportunities or threats and to proactively create new futures for the firm. As resources come into place, new opportunities and visions appear. New tactics become possible. As new tactics are used, the firm builds its speed and surprise capabilities by practicing tactics that involve speed and surprise.

FIGURE 9-9

DISRUPTION AND THE NEW 7-S’s

All three levels of the new dynamic planning model in Figure 9-9 must be focused on disruption. The New 7-S analysis for assessing competitors (illustrated by the Intel example above) has taught us that at each moment in time, the hypercompetitive firm is better than its opponents at each and every one of the New 7-S’s. The Dynamic 7-S analysis (illustrated by the watch and camera examples above) has taught us that

- the New 7-S’s have a theme or overall vision to them, such as improving the quality of amateur photos

- over time, firms disrupt the market by shifting to a new theme, such as ease of developing film

- these swings in theme can take the form of a swinging pendulum (e.g., in cameras, where the movement went back and forth between ease of development and photo quality) or a continuous series of redefinitions of accuracy and fashion (e.g., the watch industry)

Thus, in the short run the New 7-S analysis can be used to determine what types of vision, resources, and tactics are needed to win, given the nature of competition as it currently exists in an industry (e.g., the Intel example above). More important, the Dynamic 7-S analysis can be used to track the historical movement and shifts in the vision, resources, and tactics that have been used to revolutionize the industry periodically (e.g., the watch and camera examples above).

VISION FOR DISRUPTION: S-l AND S-2

The vision for the company’s next move is shaped through the first two S’s. Superior stakeholder satisfaction (S-l) and strategic soothsaying (S-2) provide insights into the existing and emerging needs of customers and into new ways of meeting those needs better than any other competitor.

They provide the basis for developing a theme for all of the New 7″S’s that disrupt the marketplace either within the current methods of competing or by inventing new methods of competing.

The Matrix in Figure 9-10 offers a useful way of analyzing the types of disruption that can be pursued by a hypercompetitive firm. It is based on selecting new or existing markets to serve and new or existing methods for serving them, as shown in Figure 9-10. By identifying which of the four squares to compete in, the company defines its next move or series of moves. Companies can jump from disruptions in one quadrant to disruptions in others, as demonstrated by the beer industry example below.

As can be seen from Figure 9-10, there are four types of disruption that can be envisioned by using the first two of the New 7’S’s. Each seizes the initiative in a different way. Hypercompetitive firms stay one step ahead of their competitors by undertaking a series of disruptions that sometimes jump from box to box in Figure 9-10.

For example, the competition in the “beer wars” between Miller and Anheuser-Busch illustrates how different visions for disruption might be created through the use of the Matrix in Figure 9-10. Miller used an understanding of the customer and strategic soothsaying to shift from one quadrant to the next. As shown in Figure 9-11, in 1970 most of the beer makers were serving the same customer without much change or improvement in their methods, other than through continuously increasing economies of scale in production. Miller disrupted the market by positioning its beer as the champagne of beers, creating a premium niche in the beer mar-ket. It then created new distribution channels and methods for selling this beer, using a national advertising campaign and other entirely new methods of serving the customer. Then Miller built on these methods to move into an entirely new market with a new brewing method when it introduced light beer and discovered that it could be positioned for women. It also moved again to serve existing customers through incremental improvements by introducing the new seven-ounce bottle. In this way Miller has disrupted the beer market by shifting its focus back and forth between existing and new customers and existing and new methods. Each new disruption was designed to seize the initiative for Miller. The sequencing was designed to maintain the momentum for Miller. (Figure 9-11 illustrates these shifts.) Unfortunately Miller lost the initiative to Anheuser-Busch, which counterattacked with many disruptions that were executed better than those used by Miller Beer. Anheuser-Busch, in particular, was gaining share due to a series of modest plant modernizations and new brewing techniques designed to serve the male beer drinker.

FIGURE 9-10

FOUR VISIONS OF HOW TO DISRUPT

MARKETS

A similar mapping can be done for many other industries. In watches (as discussed above) the vision of disruption shifted from disruptions that involved radical new methods based on quartz and digital technologies to disruptions that involved the use of fashion to capture an entirely new type of buyer.

FIGURE 9-11

A SERIES OF DISRUPTIONS IN THE BEER INDUSTRY DURING

THE EARLY 1970s

RESOURCE PLANNING: S-3 AND S-4

At the same time that companies are defining which customers to serve and how to serve them, they also look at their capabilities for carrying out that vision in the future. By building capabilities for speed (S-3) and sur- prise (S-4), they are prepared for a variety of different actions. In contrast to most resource planning, which tends to commit the company to a specific action, developing capabilities for speed and surprise still leaves the company with great flexibility. Even if competitors are aware of the company’s capacity for speed and surprise, they will not know how the company intends to use these capabilities. Competitors also may not be able to quickly duplicate these capabilities.

By assessing its strength in speed and surprise in comparison to its com- petitors, companies gain a better understanding of where their capabilities need to be strengthened. They must actively monitor whether they have the speed to carry out their vision for disrupting the market time and time again. Comparing such key indicators as product introductions or variety, speed of response to competitors’ moves, creativity in design, and flexibility, companies gain a better picture of their relative strengths.

If the company has a relative weakness in capabilities for either speed or surprise, it then car. identify ways to strengthen those weaknesses so it can move at least as quickly and stealthily as competitors. A key part of this analysis is identifying the process or structures of the company that tend to make it slower than competitors or give it less stealth. Then the company can focus on ways to shore up these weak points or turn them to its advantage. The key is active monitoring of the capabilities and proactive creation of these capabilities through investments, human resource practices, and related approaches.

PUNCH-COUNTERPUNCH PLANNING: S-5, S-6, S-7

Companies plan a series of actions to take advantage of opportunities for seizing the initiative identified through the development of a vision. They plan for their moves and their competitors’ reactions, a series of punches and counterpunches. These tactics draw upon the capabilities above, and involve shifting the rules of competition (S-5), signaling (S-6), and simul- taneous and sequential strategic thrusts (S-7).

Using speed and surprise, companies analyze the competitive environment to identify the action that would be most difficult for the opponent to foresee and most difficult for it to defend against. On the other hand, companies also avoid attacking areas where the opponent is on guard.

Companies confuse or influence their competitors through signaling (S-6). The signal is often the first punch of a series of competitive maneuvers that disrupt an opponent and create temporary advantage.

Punch-counterpunch planning offers flexibility at each stage of competition. Using simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts, companies give themselves a variety of routes they can take at any given step in the process. By analyzing the company’s vision for disruption, as described above, the company checks and adjusts its actions in pursuit of that vision.

Successful companies also emphasize deterring the opponent rather than appeasing it. Both appeasement and attempts to crush the opponent are very dangerous. Appeasement is dangerous because aggressive competitors will rarely roll over and play dead. The competitor may rise up more powerful than before. Violent aggression is also risky because it usually provokes a strong defense or aggressive response from the attacked competitor.

Companies also determine how much time and resources they are willing to devote to the actions. For example, attacking an opponent that will fight to the bitter end will require a strong and sustained desire to win on the part of the attacking firm. In analyzing potential actions, successful companies plan to use only as much force as is necessary. Otherwise it might find it is exhausted and open to counterattack.

Punch-counterpunch planning does not really result in a plan in the traditional sense of the word. Firms don’t plan out each move and countermove because, as the old military maxim goes, no plan lasts longer than contact with the enemy.

Punch-counterpunch planning is more like the preparation of a boxer before a title match. The boxer works on his repertoire of moves, stamina, and reflexes. He is building the instinct and ability to use his tactical moves instantly and with surprise. Based on the opponent’s repertoire of moves, he may even develop a game plan like Explore the competitor’s actions in the first two rounds, use the right for the next two rounds, and then go for the knockout using a combo in the fifth round. However, he never knows the exact sequence of moves that will be used until the match is in play.

2. Using the New 7-S’s in an Expanded Four Arena Analysis

Once these three parts are in place—vision, resources, and tactics—then companies use the Four Arena analysis of Part I to analyze their relative strengths and weaknesses in the four arenas. This tool can be extended by examining how the New 7-S’s enhance and build strength in each of the four arenas.

While all the New 7-S’s are important in seizing the initiative in each of the arenas, some are more important in certain arenas. Figure 9-12 contains an illustration of a hypothetical Four Arena analysis based on identifying which of the New 7-S’s is critical to winning. The critical success factors in each arena may vary from industry to industry. However, the principle remains the same.

Thus, if a company uses a Four Arena Analysis and decides to move in one of the four arenas, it can then develop the necessary New 7-S’s to seize the initiative in that arena. At the same time, companies look at the strengths of their competitors in the New 7-S’s to determine opportunities in each arena. Among the ways companies use the New 7-S’s to seize the initiative are

FIGURE 9-12

A HYPOTHETICAL EXPANDED FOUR-ARENA ANALYSIS

- to speed ahead of competitors and stay one or two rungs ahead on the escalation ladders described in Part I.

- to restart the cycle of competition. For example, a company shifts the rules to create a new quality dimension in the first arena (cost-quality).

- to run two cycles simultaneously in the same arena. For example, the company might redefine quality differently at the high end versus the low end of the market.

- to jump to a new arena, as described in Part I. Using surprise, for example, the company could roll out a product or process innovation or attack a competitor’s stronghold.

- to jump back to an old arena where competition has been ignored or has died down. After moving into competition on technological know-how, a company may drive the competition back to cost and quality.

A careful examination of the New 7-S’s will indicate which of these are doable and which of the New 7-S’s are necessary to carry each of these out.

3. Tradeoff Analysis: Selecting among the New 7-S’s

One final analysis can be done using the New 7-S’s. In choosing which to concentrate on, companies are forced to make tradeoffs among them. This makes it difficult for companies to do all seven equally well. Companies choose among the seven to confront different challenges and opportunities that present themselves.

Thus, it is possible to analyze a competitor (or one’s own company) to see what types of tradeoffs have been made. Once these are identified, the weakness of the competitor (or one’s own company) is apparent. Furthermore, the tradeoff means that the competitor can’t plug the weakness without giving up something else. Thus, it is possible to identify weakness, which, if attacked, forces the competition to be slow to respond or to give up some other strength in order to respond. Either way the competitor loses.

Among the tradeoffs implied by the New 7-S’s are the following:

- Tradeoffs at the expense of stakeholder satisfaction (S-1) can be undermined by speed (S-3), as companies may sacrifice product or service quality to gain speed or push employees to work harder and faster. Speeding products to market with little testing could also reduce customer satisfaction. Similarly surprise (S-4), shifting the rules (S-5), signaling (S-6), and simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts (S-7) also have the potential to confuse customers, employees, and shareholders as well as competitors.

- Tradeoffs at the expense of future orientation/soothsaying Strategic soothsaying (S-2) can be hurt by speed (S-3), which often leaves little time for reflecting on what lies ahead, and surprise (S-4), which is sudden and unpredictable enough to make prognostication irrelevant or impossible. Shifting the rules (S-5) often reshapes competition in a way that unpredictably changes future opportunities so that soothsaying becomes difficult. To the extent that competitor reactions are not anticipated, simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts (S-7) sometimes make soothsaying more difficult.

- Tradeoffs at the expense of speed Speed (S-3) can be eroded through the slowness of decision making in an inverted organization such as the ones used to increase stakeholder satisfaction (S-l). Also, strategic alliances used to shift the rules (S-5) sometimes reduce speed because of negotiations. Shifting the rules of competition (S-5) may require a tradeoff with speed. It can temporarily reduce speed (S-3), for example, because of the confusion and time it takes to regroup and retool to create the new rules. Simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts (S-7) can reduce speed (S-3) because they require more effort than single thrusts.

- Tradeoffs at the expense of surprise The flexibility and stealth of surprise (S-4) can be eroded by strategies to increase capabilities for speed. For example, just-in-time systems could decrease the company’s flexibility while increasing speed. Alliances to shift the rules sometimes also decrease surprise because the alliances are usually public. Signaling can also reduce the element of surprise because it often involves revealing the strategic intent of the company. Sequential thrusts can reduce surprise (S-4) by committing the company to a clear set of actions.

These tradeoffs mean that firms can’t always do all of the New 7-S’s equally well, even if they are above a reasonable threshold on each one of them. Thus, a competitor can do a tradeoff analysis to identify the maneuvers it can do through use of the S’s that the opponent can’t do well because the opponent can’t respond without depleting its strength in one of the other S’s. Other firms will creatively switch between the New 7-S’s to shift the rules of competition, sometimes focusing on the opponent’s weaker S’s, sometimes using several in concert.

Moreover, firms have limited resources, so they can’t acquire all seven of the New S’s at once. They must prioritize them and make tradeoffs. Thus, it will be rare that a firm is equally good at all of the New 7-S’s. This will create opportunities for a new type of hypercompetitive behavior whereby firms use the resource investments tradeoff made by a competitor to determine which of the New 7-S’s should be invested in first. Finally, truly hypercompetitive firms, like Intel, will find ways to eliminate the tradeoffs. Tradeoffs exist only if firms believe that tradeoffs are necessities and stop looking for ways to do both alternatives. After all, it was once said that firms could not achieve low cost and high quality at the same time. Now it is not just a reality but a necessity for survival in many industries.

Source: D’aveni Richard A. (1994), Hypercompetition, Free Press.