We have seen that Menger’s story is an abstract one. It isolates market mecha- nisms and economising individuals to explain the emergence of money as a me- dium of exchange. We have also seen that he is abstracting from some institutions that seems to be important in the genesis of money, such as gift giving, obligatory payments, etc. But, although Menger is ignoring some relevant factors in his sto- ry, he may be interpreted as providing a new look at the process of emergence of money by showing how interaction of economising individuals may bring about money. There is nothing in Menger’s explanation that would prevent us from integrating particular institutional factors to our explanation of particular cases of emergence of money. The apparent conflict between Menger’s account and its rivals disappears if we consider Menger as providing a partial potential theoreti- cal explanation of the genesis of money.

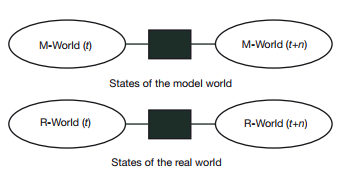

In contrast to Figure 3.1, Figure 3.2 illustrates two different worlds: the real world (R-World) and the model world (M-World). M-World is an abstract world (i.e. a model) that is supposed to represent the real world, R-World. R-World (t) shows a particular state of the real world where a medium of exchange is non- existent. R-World (t + n) illustrates a later state of the real world where individuals are using a medium of exchange.

In order to explain the emergence of money one has to tell us how R-World (t) was transformed to R-World (t + n). There may be two different ways of do- ing this. First, one may give a historical explanation of this transformation by narrating the time- and place-specific details of the process of emergence of money. Although such an explanation would use some abstractions and isola- tions, we would expect it to be accurate about the time- and place-specific details. In Merger’s terms such an explanation could be considered as conforming to the realist–empirical orientation. A second strategy that could be followed in order to explain the transformation of R-World (t) into R-World (t + n) is to abstract from the complexities of the real world and try to find out some of the general mechanisms that may have brought about a medium of exchange. This would involve creation of a model world (M-World) which is isolated from the particular details of the real world. Such an explanation would tell us how the model world is transformed from a state with no medium of exchange (M-World (t)) to a state with a medium exchange (M-World (t + n)). In principle, we would not expect this explanation to give us a fully accurate representation of states of the real world, as long as it unearths some of the causal mechanisms that drive the process of emergence of money. In Merger’s terms, such an explanation could be considered as conforming to the exact orientation.

Figure 3.2 Real world vs. model world.

Note that Menger’s arguments about exact understanding indicate that a theo- retical explanation is an explanation in an abstractly conceived world.27 That is, M-World (t) and the mechanisms therein (e.g. economising actions of individu- als and their interaction) explain its transformation into M-World (t + n). Then, a theoretical explanation may be defined as an explanation of the state of the affairs in a model world. A historical explanation, on the other hand, is an explanation of the state of the affairs in the real world. The states of affairs in the real world are specific to time and place, thus their explanation would be an explanation of particular facts. To be consistent with the philosophical literature let us call these singular explanations (see Ruben 1992: 4). Roughly, singular explanations explain the transformation of R-World (t) into R-World (t + n) by pointing out the particular facts concerning the particular states of the real world.28 A theoretical explanation on the other hand needs to uncover the general (causal) mechanisms or ‘laws’ that drive the process of emergence of money. Certainly, we would ex- pect theoretical explanations to help us explain particular cases.

Since a singular explanation (historical explanation in Menger’s terminology) is an explanation that is specific to a certain space and time, the important ques- tion is whether there is any sensible relation between states of the model world and the states of the real world that will allow us to use our theoretical explanation to explain particular cases. Or more generally, whether there is a relation (e.g. a certain amount of similarity) between the real world and the model world that will allow us to carry our explanation from the model world to the real world. A theoretical explanation may help us explain particular cases if it satisfies the following conditions:

- the explanation has to be successful in explaining the states of affairs in the model world; and

- there must be some similarity between the model world and the real world.

As for the first condition, Menger’s story could be considered as a logically plausible story of the transformation of M-World (t) into M-World (t + n). To see this we may imagine that there is a possible world that satisfies the conditions de- fined by Menger for M-World (t) and the individuals therein. There is nothing in Menger’s story that would make us think that such a possible world would not be transformed into a world with a medium of exchange by the mechanisms defined by Menger. This is why we may consider Menger’s story as being logically plau- sible. Yet we may not argue that it is a logical necessity that M-World (t) would be transformed into M-World (t + n). The deficiency of Menger’s theoretical ex- planation is that the workings of the mechanisms of this transformation are not entirely clear.29 This leaves the possibility that more constraints may apply to his explanation. For example, it may be that under some conditions market exchange does not lead to money as a medium of exchange. Hence, Menger’s explanation does not establish the logical necessity of the transformation of M-World (t) into M-World (t + n). The emergence of money in the model world is not explained in a satisfactory manner because the causal mechanisms and the conditions under which they will bring about a medium of exchange are not fully explicated. Thus, Menger’s explanation partly fails to satisfy the first condition. His explanation is just a logically plausible story of the emergence of money.

As for the second condition, we have seen that M-World (t) does not really correspond to any particular stage of the real world. Yet we may try to see whether there are some similarities that would let us carry the partial success of the story in the model world to the real world. One of the reasons why Menger’s logically plausible story may present some real world mechanisms is that his story is con- strained by the relevant facts about the real world. For example, although M-World

(t) did not exist exactly as it is in history, we know that whatever their institutional structure may have been, cultures that were using a medium of exchange passed from a stage where most of the individuals were dependent on market exchange (e.g. because of specialisation).30 We know that if individuals have to exchange goods at the market to acquire the necessities of life, it would be inconvenient to exchange goods directly. We also know that human beings have the ability to discover, learn and imitate. Thus, it seems highly plausible that under the condi- tions of market-dependent direct exchange some individuals would start using more saleable goods to mediate their exchange and others would be following them. Moreover, Menger’s theory of saleableness is broad enough to encompass some pre-existing forms of limited-purpose money. That is, if there are certain goods that serve some functions of money (e.g. means of payment for particular institutional obligations) in R-World (t), we may consider these commodities as highly saleable compared to others and start our analysis from there. More impor- tantly, the explanatory mechanisms depicted in Menger’s logically plausible story are familiar to us. Individuals tend to economise (e.g. minimise transaction costs) under conditions of market-dependent exchange. Individuals have a tendency to discover new and more economical ways of doing things, and they imitate other successful individuals. Actions individuals who economise, discover and imitate could be considered as the main causal mechanisms in Menger’s story. The inter- action of these individual mechanisms (i.e. economising individuals) brings about a commonly accepted medium of exchange. The similarity between the abstract world depicted by Menger and the real world boils down to these mechanisms. We find Menger’s explanation plausible because of our familiarity with these mechanisms. We feel that what happens in Menger’s model world may have taken place in the real world.

We will have more to say about the distinction between individual mechanisms and their interaction in the next chapter. It is sufficient here to state that our fa- miliarity with the individual mechanisms described by Menger turns his logically plausible story into a ‘humanly possible’ scenario. Nevertheless, ‘humanly pos- sible’ is still possible. Menger is pointing out to a possible way in which certain existent mechanisms (e.g. economising action of separate individuals, imitation and learning) may interact and bring about money. Or more correctly, he is point- ing out to some of the mechanisms that may partly explain the emergence of a me- dium of exchange albeit the workings of these mechanisms are not well defined.

Until now we have seen that Menger does not fully satisfy the conditions that will help us carry his theoretical explanation to the real world to explain particular facts. However, we should not forget the difficulty of Menger’s task. Let us con- sider Menger’s explanation from a different perspective in order to appreciate his partial success. We need to grant the fact that explaining the origin of money is a challenging task. Societies can be considered as a complex web of many institu- tions, and in every society this web is composed in a different way. The origin of money in a particular society cannot be thought of independently from its web of institutions. Yet, we neither have the complete and detailed historical record of the process of the emergence of money, nor do we have the chance to observe its emergence again. We may have evidence about the types of money used in certain societies and some of their institutions, but we may not start from here and deduce the causal mechanisms behind the emergence of money. In fact, we may consider explaining the origin of money as being somewhat similar to explaining the origin of life. We observe that there are living organisms with certain properties and we have some information about the earlier stages of the world prior to the develop- ment of living organisms, but we can do nothing but conjecture about the possible processes through which living organisms have developed. We constrain these conjectures with the known facts about living beings, and try to produce a plau- sible story of the emergence of life on Earth. It may be that our depiction of the earlier stages of the earth is inaccurate, but still these conjectures provide us with a framework within which we may reconsider the way in which certain factors and mechanisms have interacted in bringing about life on Earth. That is, if we are able to produce a plausible story of the emergence of life that would be a story of the transformation of M-World (t) into M-World (t + n). This seems to be the only way to proceed unless we are able to observe the state of the real world prior to the existence of life, R-World (t). Once we have a plausible story of the emergence of life, we may proceed to test our conjecture. We may test our conjecture logically by way of examining our model world under various conditions. Or, we may em- pirically test it by conducting experiments. The aim of this investigation would, of course, be to understand whether the explanatory mechanisms in our plausible conjecture are the real mechanisms behind the emergence of life.

Similarly, we may conceive Menger’s story as alerting us to a possible way in which mechanisms of economising, imitation and learning may have interacted in the process of the emergence of a medium of exchange. Menger’s conjecture alerts us to certain explanatory factors (mechanisms) that may have been impor- tant in the development of a medium of exchange.31 At the time of its proposal, it presented an alternative way of thinking about the emergence of a medium of ex- change. At least, he informed the audience that pointing out to the historical cases of the emergence of coined money cannot be the whole story of the emergence of money. He showed that although coined money may simply be a matter of design, the real problem was in explicating the stages prior to the decision of introducing coining money and the mechanisms that have transformed a no-money world in to a world with a medium of exchange. We may argue that he expanded the mental horizon of his audience by introducing an alternative process of the emergence of money. It was an important proposal to be tested logically and empirically. It was a step – a partial and incomplete step – forward in explaining the origin of money, an attempt to discover the real story behind the emergence of money.

Despite its deficiencies, the value of Menger’s theoretical explanation comes from his exposition of the importance of market-dependent exchange, economis- ing actions and learning.32 Menger’s story is not a full-fledged explanation of the origin of money. It is a partial explanation for it alerts us to some of the explana- tory factors. It is a potential explanation for it alerts us to a set of possible explana- tory factors. We do not know whether the proposed individual mechanisms were really responsible for the emergence of money. In this sense, the weakness of the objections to Menger’s explanation is that they do not consider the possible importance of proposed explanatory mechanisms in explaining the emergence of money as a medium of exchange. If Menger is right in saying that the exact and empirical orientations of research should go hand in hand, we may argue that historical explanations of the emergence of a medium of exchange should at least consider investigating whether economising actions of individuals, discovery and imitation played any role in its emergence.

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.