Formulating horizontal strategy involves a number of analytical steps that flow from the framework described in Chapter 9:

- Identify all tangible interrelationships. The starting point in formulating horizontal strategy is to identify systematically all the tangible interrelationships that are actually or potentially present among a firm’s business units. The first step in doing so is to examine value chains of each business unit for actual and possible opportunities for sharing. Initially, all interrelationships that seem to be present should be identified; illusory or insignificant interrelationships can be eliminated through further analysis. In searching for interrelationships, the specific characteristics of value activities that would provide a basis for sharing must be identified. For example, meaningful production interrelationships must be based on similarities in specific production equipment or process steps rather than a generalized view that there are similar processes. Similarly, specific technologies and subtech- nologies are the basis of technology interrelationships, and common decision makers in buyers or channels are the basis of key market interrelationships.

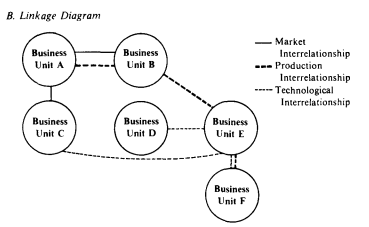

Diagrams like Figure 10-1 provide a simple mechanism to use in identifying interrelationships within a firm.

Figure 10-1. Tangible Interrelationships in a Diversified Firm

Each cell of the interrelationship matrix displays the interrelationships between a pair of business units, drawing from the types of interrelationships expressed in Table 9-1 in the previous chapter. If interrelationships are extensive, a separate matrix can be prepared for each type of interrelationship. The linkage diagram is another way to display interrelationships that may be clearer if there are a manageable number of business units. It allows the clustering of business units that have strong interrelationships, and can facilitate the visualization of groupings of units that could be the basis for groups or sectors. Whatever graphical tool one uses, interrelationships should be divided into potential interrelationships and those that are actually being achieved.

There are often many different interrelationships within a diversified firm. Different groups of business units are frequently related in different ways. One group of business units may be related by their markets, while a different, but partially overlapping, group of business units is related in production. The interrelationship matrix in Figure 10-1 illustrates one such pattern, where business units 1, 3, and 4 have a common component and common raw material, while business units 1, 2, and 3 have a common buyer.

In a diversified firm with many business units, a complex pattern of interrelationships often emerges. To simplify the analytical task of identifying interrelationships, it may be possible to break up a diversified firm into a number of clusters of business units that have many interrelationships among themselves, but relatively few with other clusters. The correspondence of such clusters to the groups or sectors that have been established is a subject to which I will return in Chapter 11. Where the interrelationships between two business units are pervasive and involve many significant value activities, the business unit definitions are probably inappropriate. The issues in drawing business unit boundaries have been discussed in Chapter 7.

- Trace tangible interrelationships outside the boundaries of the firm. A firm will rarely compete in all the industries that are related to its current business Thus, it is necessary to identify interrelationships between a firm’s existing business units and other industries not currently in its portfolio. This requires that a firm examine important value activities to look for related industries where sharing or further sharing might be feasible. A firm with an effective sales force serving a particular buyer group, for example, should identify other products purchased by the same buyer group or products that fit the sales force’s expertise that might be sold to other buyer groups. Similarly, each brand name, distribution channel, logistical system, technological development activity, and other important value activity should be probed for potential opportunities for sharing with other industries.

Identifying paths of interrelationship outside a firm is a creative task, but one that will yield considerable benefits in diversification planning and in the development of defensive strategies to anticipate and block potential entrants. The portfolios of diversified competitors can often provide important clues to industries with important interrelationships to the firm’s. However, detecting new interrelationships not exploited by any competitor can be even more valuable.

- Identify possible intangible interrelationships. After identifying tangible interrelationships, the next step is to seek out intangible inter- relationships. This involves the isolation of value activities in which a firm has valuable know-how that might be useable in other business units or in new industries. It also requires identifying new industries in which a presence would lead to know-how that is valuable in the firm’s existing business units. Signals of potential intangible interrelationships include similarities in generic strategy, buyer type, or value chain configuration. While identifying intangible interrelationships is subtle, it can be important. Many potential intangible interrelationships are usually present, which makes screening them to access their importance to competitive advantage an essential task.

- Identify competitor interrelationships. A firm must identify all its multipoint competitors, potential multipoint competitors, and competitors pursuing different patterns of interrelationships. A diagram such as that in Figure 9-4 above can provide a structure for doing so. The existence of multipoint competitors often provides dues about the presence of interrelationships, and can aid in their identification. Conversely, interrelationships often are useful predictors of potential new competitors, as described above. After the array of multipoint competitors has been identified from a firm wide perspective, the interrelationships within each important competitor’s portfolio must be charted. Often competitors have different interrelationships that involve different sets of businesses.

- Assess the importance of interrelationships to competitive advantage. The net competitive advantage from a tangible interrelationship is a function of the advantage from sharing, the costs of sharing, and the difficulty of matching the interrelationship. Shared activities must be measured against the corresponding activities of competitors on all three dimensions. The tangible interrelationships present in a diversified firm are often numerous. However, experience has shown that the number with strategic importance is likely to be relatively small. The challenge is to isolate the important ones, including those that involve industries in which a firm has no presence currently. The fact that an interrelationship is not being achieved is not a reliable sign that it is not important. The interrelationship may have been overlooked, or the costs of compromise associated with it may be reduced by making business unit strategies more consistent.

Intangible interrelationships lead to competitive advantage if the benefits of transferring know-how exceed the cost of transferring it. Transferring know- how is beneficial if the similarities among value activities are significant, the activities are important to competitive advantage in the industries involved, and the firm has know-how that can materially enhance competitive advantage if it is transferred. Experience suggests that skepticism is warranted in assessing intangible interrelationships to avoid pursuing intellectually plausible but practi- cally useless similarities among businesses.

- Develop a coordinated horizontal strategy to achieve and enhance the most important interrelationships. Important interrelationships can be achieved or enhanced in a variety of ways.

Share Appropriate Value Activities. Value activities of related business units should be shared if the benefits exceed the costs. This may involve measures such as combining sales forces, rationalizing manufacturing facilities, coordinating procurement, and rebranding product lines. Sharing will always require some adjustments to current practices. Business unit strategies may need to be modified to gain maximum advantage from sharing. Similarly, activities may have to be redesigned to reduce the cost of compromise.

Coordinate Strategic Postures of Related Business Units. The strategies of related business units should be coordinated to increase the competitive advantage of interrelationships and reduce the costs of compromise. This can involve everything from minor adjustments of business unit strategies to major repositionings, including acquisitions and divestitures. The coordination of strategies requires that marketing programs and investment spending plans are consistent, and that business units are aware of each other’s plans in product development and other important areas. Coordination also implies that actions toward competitors are part of an integrated group, sector, or corporate battle plan. Market interrelationships often create the greatest need for consistent business unit strategies, in order to gain the maximum impact with common customers or channels. However, a degree of consistency is required for achieving and exploiting any form of interrelationship. Coordinating business units can involve difficult tradeoffs between enhancing interrelationships and the position of individual business units. These tradeoffs are often difficult. However without a horizontal strategy they will rarely even be considered regardless of the benefits to the firm.

Distinguish the Goals of Business Units. The goals of business units should be set to reflect the role of business units in interrelationships. Some business units, for example, might be given more ambitious sales targets but lower profit goals because of the contribution of their volume to the position of other business units. Asking all business units to meet the same goals may seem to be the “fairest” solution, but it also threatens to undermine some important sources of competitive advantage.

Business unit goals that reflect interrelationships are broader than those prescribed in portfolio planning techniques, commonly involving mandates such as build, hold, or harvest. Portfolio models typically ignore interrelationships, and set different goals for business units only in the sense that some business units are expected to generate cash while other are expected to use it. Interrelationships provide a broader perspective of corporate strategy based on competitive advantage, within which cash flow considerations are subsumed.

Coordinate Offensive and Defensive Strategies Against Multipoint Competitors and Competitors with Different Interrelationships. There must be an overall firm game plan for dealing with each significant multipoint competitor and each competitor with a different pattern of interrelationships that could be threatening. Ideally, a firm should seek to promote industry evolution in directions that increase the value of its interrelationships and compromise the value of competitors. More specific options for offensive and defensive strategy are discussed in Chapters 14 and 15.

Exploit Important Intangible Interrelationships through Formal Programs for Exchanging Know-How. A firm must actively encour-age the transfer of know-how among business units with potentially important generic similarities. Receiving business units may not be receptive because of “not invented here” problems, and business units asked to transfer expertise may resent the commitment of time and people involved. Achieving intangible interrelationships will require a shared understanding of their value, and organizational mechanisms to facilitate the transference of know-how.

Diversify to Strengthen Important Interrelationships or Create New Ones. Diversification strategy should focus on finding and entering new businesses that reinforce the most important interrelationships or creating new interrelationships of high strategic importance. Diversification strategy will be treated in the next section.

Sell Business Units That Do Not Have Significant Interrelationships with Others or That Make the Achievement of Important Interrelationships More Difficult. Business units that have no important interrelationships to others in a firm or are not likely bases of further diversification are candidates for sale in the long term. Even if they are attractive and profitable, such business units will be worth as much or even more to other owners, since being part of the firm does not enhance their competitive advantage and being part of another firm might. A firm can thus be in a position to recover the full value to it or more of such business units by selling them. The proceeds can then be invested in business units where interrelationships can enhance competitive advantage. Practical considerations mean that such a strategy may have to be implemented over the long-term, however. Buyers that recognize the value of a business unit may not be easy to find, and it may be hard to replace a highly profitable, albeit unrelated business unit with an equally attractive one, no matter how great the potential interrelationships might be.

The presence of some marginally related business units may make it more difficult to achieve other, more important interrelationships. They, too, are candidates for sale. A firm may be less able to build a shared distribution channel, for example, if it has another business unit that uses a different and competing channel to reach the same buyer group. Similarly, a firm may be less able to exploit opportunities for sharing a sales force and marketing to reach a particular buyer group if it has a business unit in the buyer group’s industry that competes with it. Interrelationships may create conflicts with buyers, suppliers, or channels. American Express has experienced this as it increasingly competes with banks which are also a key outlet for its travelers checks. Unlocking some interrelationships, then, may require a firm to get out of some industries.

When there are several patterns of interrelationships within a firm involving different groups of business units, taking some of the steps noted above may involve tradeoffs. Coordinating strategic postures to facilitate one type of interrelationship can reduce the ability to achieve another. Distinguishing business unit goals can lead to the same sort of tradeoff. Where such tradeoffs exist, the principle must be to reinforce those interrelationships that have the greatest impact on competitive advantage, even at the expense of others. However, organizational mechanisms described in the next chapter can often allow interrelationships among different groups of business units to be achieved simultaneously.

- Create horizontal organizational mechanisms to assure imple- mentation. Firms cannot successfully exploit interrelationships without a horizontal organizational structure that encourages coordination and transfers skills across business unit lines. Such tasks as defining the right business units, clustering them into the proper groups and sectors, and establishing incentives for business unit managers to work together are vital to success. The principles of horizontal organization are the subject of Chapter 11.

Source: Porter Michael E. (1998), Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press; Illustrated edition.