Theory linked with Swedish political scientist RUDOLF KJELLEN (1864-1922) and German political geographer Karl Haushofer (1869-1946).

Nations are understood as analogous to natural organisms, competing for geographical space.

An archaic theory.

Source:

Roger Scruton, A Dictionary of Political Thought (London, 1982)

United States

Alfred Thayer Mahan and sea power

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914) was a frequent commentator on world naval strategic and diplomatic affairs. Mahan believed that national greatness was inextricably associated with the sea—and particularly with its commercial use in peace and its control in war. Mahan’s theoretical framework came from Antoine-Henri Jomini, and emphasized that strategic locations (such as choke points, canals, and coaling stations), as well as quantifiable levels of fighting power in a fleet, were conducive to control over the sea. He proposed six conditions required for a nation to have sea power:

- Advantageous geographical position;

- Serviceable coastlines, abundant natural resources, and favorable climate;

- Extent of territory

- Population large enough to defend its territory;

- Society with an aptitude for the sea and commercial enterprise; and

- Government with the influence and inclination to dominate the sea.[11]

Mahan distinguished a key region of the world in the Eurasian context, namely, the Central Zone of Asia lying between 30° and 40° north and stretching from Asia Minor to Japan.[12] In this zone independent countries still survived – Turkey, Persia, Afghanistan, China, and Japan. Mahan regarded those countries, located between Britain and Russia, as if between “Scylla and Charybdis”. Of the two monsters – Britain and Russia – it was the latter that Mahan considered more threatening to the fate of Central Asia. Mahan was impressed by Russia’s transcontinental size and strategically favorable position for southward expansion. Therefore, he found it necessary for the Anglo-Saxon “sea power” to resist Russia.[13]

Homer Lea

Homer Lea, in The Day of the Saxon (1912), described that the entire Anglo-Saxon race faced a threat from German (Teuton), Russian (Slav), and Japanese expansionism: The “fatal” relationship of Russia, Japan, and Germany “has now assumed through the urgency of natural forces a coalition directed against the survival of Saxon supremacy.” It is “a dreadful Dreibund”.[14] Lea believed that while Japan moved against Far East and Russia against India, the Germans would strike at England, the center of the British Empire. He thought the Anglo-Saxons faced certain disaster from their militant opponents.

Kissinger, Brzezinski and the Grand Chessboard

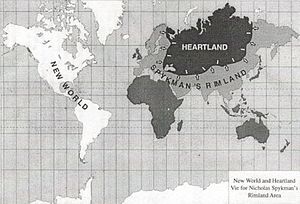

World map with the concepts of Heartland and Rimland applied

Two famous security advisors from the cold war period, Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski, argued to continue the United States geopolitical focus on Eurasia and, particularly on Russia, despite the dissolution of the USSR and the end of the Cold War. Both continued their influence on geopolitics after the end of the Cold War,[5] writing books on the subject in the 1990s—Diplomacy and The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives.[15] The Anglo-American classical geopolitical theories were revived.

Kissinger argued against the belief that with the dissolution of the USSR, hostile intentions had come to an end and traditional foreign policy considerations no longer applied. “They would argue … that Russia, regardless of who governs it, sits astride the territory which Halford Mackinder called the geopolitical heartland, and it is the heir to one of the most potent imperial traditions.” Therefore, the United States must “maintain the global balance of power vis-à-vis the country with a long history of expansionism.”[16]

After Russia, the second geopolitical threat which remained was Germany and, as Mackinder had feared ninety years ago, its partnership with Russia. During the Cold War, Kissinger argues, both sides of the Atlantic recognized that, “unless America is organically involved in Europe, it would later be obliged to involve itself under circumstances which would be far less favorable to both sides of the Atlantic. That is even more true today. Germany has become so strong that existing European institutions cannot strike a balance between Germany and its European partners all by themselves. Nor can Europe, even with the assistance of Germany, manage […] Russia” all by itself. Thus Kissinger believed that no country’s interests would ever be served if Germany and Russia were to ever form a partnership in which each country would consider itself the principal partner. They would raise fears of condominium.[clarification needed] Without America, Britain and France cannot cope with Germany and Russia; and “without Europe, America could turn … into an island off the shores of Eurasia.”[17]

Spykman’s vision of Eurasia was strongly confirmed: “Geopolitically, America is an island off the shores of the large landmass of Eurasia, whose resources and population far exceed those of the United States. The domination by a single power of either of Eurasia’s two principal spheres—Europe and Asia—remains a good definition of strategic danger for America. Cold War or no Cold War. For such a grouping would have the capacity to outstrip America economically and, in the end, militarily. That danger would have to be resisted even if the dominant power was apparently benevolent, for if its intentions ever changed, America would find itself with a grossly diminished capacity for effective resistance and a growing inability to shape events.”[18] The main interest of the American leaders is maintaining the balance of power in Eurasia[19]

Having converted from an ideologist into a geopolitician, Kissinger retrospectively interpreted the Cold War in geopolitical terms—an approach which was not characteristic of his works during the Cold War. Now, however, he focused on the beginning of the Cold War: “The objective of moral opposition to Communism had merged with the geopolitical task of containing Soviet expansion.”[20] Nixon, he added, was a geopolitical rather than an ideological cold warrior.[21]

Three years after Kissinger’s Diplomacy, Zbigniew Brzezinski followed suit, launching The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives and, after three more years, The Geostrategic Triad: Living with China, Europe, and Russia. The Grand Chessboard described the American triumph in the Cold War in terms of control over Eurasia: for the first time ever, a “non-Eurasian” power had emerged as a key arbiter of “Eurasian” power relations.[15] The book states its purpose: “The formulation of a comprehensive and integrated Eurasian geostrategy is therefore the purpose of this book.”[15] Although the power configuration underwent a revolutionary change, Brzezinski confirmed three years later, Eurasia was still a mega-continent.[22] Like Spykman, Brzezinski acknowledges that: “Cumulatively, Eurasia’s power vastly overshadows America’s.”[15]

In classical Spykman terms, Brzezinski formulated his geostrategic “chessboard” doctrine of Eurasia, which aims to prevent the unification of this mega-continent.

“Europe and Asia are politically and economically powerful…. It follows that… American foreign policy must…employ its influence in Eurasia in a manner that creates a stable continental equilibrium, with the United States as the political arbiter.… Eurasia is thus the chessboard on which the struggle for global primacy continues to be played, and that struggle involves geo- strategy – the strategic management of geopolitical interests…. But in the meantime it is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges, capable of dominating Eurasia and thus also of challenging America… For America the chief geopolitical prize is Eurasia…and America’s global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained.”

I’d must check with you here. Which is not something I usually do! I enjoy reading a put up that can make folks think. Also, thanks for allowing me to remark!

I got this web site from my buddy who informed me on the topic of this web

page and now this time I am browsing this site and reading very informative posts

at this time.

It’s actually a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you simply shared

this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date

like this. Thank you for sharing.