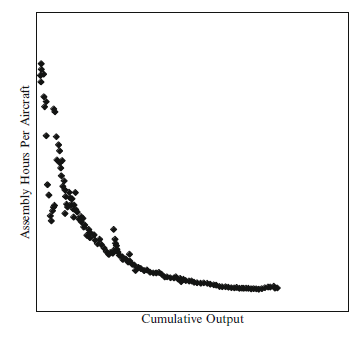

“Learning curves” have been found in many organizations. As organizations produce more of a product, the unit cost of production typically decreases at a decreasing rate. A learning curve for the production of an advanced military jet built in the 1970s and 1980s is shown in Fig. 1.1. The number of direct labor hours required to assemble each jet aircraft is plotted on the vertical axis; the cumulative number of aircraft produced is plotted on the horizontal axis. As can be seen from Fig. 1.1, the number of direct labor hours required to assemble each aircraft decreased significantly as experience was gained in production, and the rate of decrease declined with rising cumulative output. This and related phenomena are referred to as learning curves, progress curves, experience curves, or learning by doing.

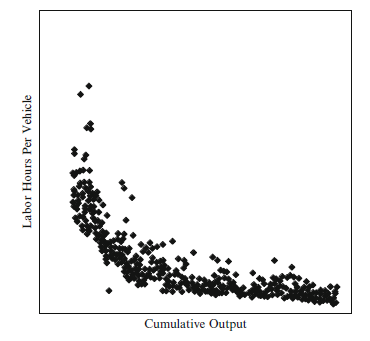

This learning-curve pattern has been found in many organizations. Figure 1.2 shows a learning curve for a truck assembly plant. The number of direct labor hours required to assemble each vehicle is plotted on the vertical axis; the cumulative number of trucks produced is plotted on the horizontal axis. Figure 1.2 depicts the classic learning-curve pattern: the number of labor hours required to assemble each vehicle decreased at a decreasing rate as experience was gained in production.

The unit cost of producing discrete products such as aircraft (Alchian, 1963; Asher, 1956; Wright, 1936), ships (Rapping, 1965), trucks (Epple, Argote, & Murphy, 1996), and semiconductors (Gruber, 1994) have all been shown to follow a learning curve. The production of continuous products such as refined petroleum (Hirschmann, 1964) and chemicals (Lieberman, 1984) have also been found to exhibit learning. Additionally, learning curves have been found to characterize a wide range of outcomes in very different settings, including success rates (Kelsey et al., 1984) and completion times (Reagans, Argote, & Brooks, 2005) for surgical procedures, nuclear plant operating reliability (Joskow & Rozanski, 1979), produc- tivity in kibbutz farming (Barkai & Levhari, 1973) and pizza production (Darr, Argote, & Epple, 1995).

Fig. 1.1 The relationship between assembly hours per aircraft and cumulative output. Note: Reprinted with permission from L. Argote and D. Epple, Learning curves in manufacturing, Science, Volume 247, Number 4945 (February, 1990). Copyright 1990, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The productivity gains derived from organizational learning are significant. For example, during the first year of production of Liberty Ships during World War II, the average number of labor hours required to produce a ship decreased by 45%, and the average time it took to build a ship decreased by 75% (Searle & Gody, 1945). During the first year of operation of a truck assembly plant, the plant’s pro- ductivity grew by approximately 190% (Epple, Argote, & Devadas, 1991).

Although the learning-curve pattern has been found in many organizations, orga- nizations vary considerably in the rates at which they learn (Argote & Epple, 1990; Dutton & Thomas, 1984; Hayes & Clark, 1986). Some organizations evidence extraordinary rates of productivity growth with experience; others fail to exhibit productivity gains from learning. Understanding the contrast between organizations that evidence little or no productivity growth with experience and those that show remarkable rates of learning is an important undertaking. For organizations to com- pete effectively, we need to understand why some organizations show rapid rates of learning and others fail to learn. A greater understanding of factors responsible for the variation observed in organizational learning rates is needed.

Many researchers have emphasized the importance of understanding the variation observed in organizational learning rates. Dutton and Thomas (1984), Lieberman (1984), and Lucas (1993) concluded that the dynamics underlying the learning curve are poorly understood. Similarly, Yelle (1979) indicated that a better under- standing of the contributions of various factors to learning curves is needed. This monograph aims to advance knowledge about factors explaining the variation observed in organizational learning curves—to explain why some organizations are better at learning than others.

This chapter began with a discussion of the classic learning curve. It continues with a brief historical overview of the phenomenon, and recent trends in research are noted.

Fig. 1.2 The relationship between labor hours per vehicle and cumulative output. Note: Reprinted by permission from L. Argote, D. Epple and K. Murphy, An empirical investigation of the micro structure of knowledge acquisition and transfer through learning by doing, Operations Research: Special Issue on New Directions in Manufacturing, Volume 44, Number 1 (January–February, 1996). Copyright 1996, The Institute of Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS), 7240 Parkway Drive, Suite 300, Hanover, MD 21076 USA. Units omitted to protect confidentiality of data

How organizational knowledge is typically measured in the learning-curve frame- work is described and how learning is assessed is discussed. The chapter then pres- ents evidence that learning rates vary tremendously across organizations. Theoretical models that aim to explain the variation observed in learning rates are presented. The chapter concludes with a discussion of learning-curve applications aimed at improving firm performance.

Source: Argote Linda (2013), Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge, Springer; 2nd ed. 2013 edition.