Ideas

Ideas

– Man is by nature good; society is the cause of corruption and vice.

– In a state of nature, the individual is characterized by healthy self-love; self-love is accompanied by a natural compassion.

– In society, natural self-love becomes corrupted into a venal pride, which seeks only the good opinion of others and, in so doing, causes the individual to lose touch with his or her true nature; the loss of one’s true nature ends in a loss of freedom.

– While society corrupts human nature, it also represents the possibility of its perfection in morality.

– Human interaction requires the transformation of natural freedom into moral freedom; this transformation is based on reason and provides the foundation for a theory of political right.

– A just society replaces the individual’s natural freedom of will with the general will; such a society is based on a social contract by which each individual alienates all of his or her natural rights to create a new corporate person, the sovereign, the repository of the general will.

– The individual never loses freedom, but rediscovers it in the general will; the general will acts always for the good of society as a whole.

Biography

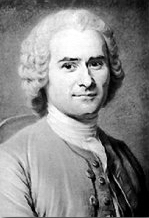

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva but became famous as a ‘French’ political philosopher and educationalist. Rousseau was brought up first by his father (Issac) and an aunt (his mother died a few days after his birth), and later and by an uncle. He had happy memories of his childhood – although it had some odd features such as not being allowed to play with children his own age. His father taught him to read and helped him to appreciate the countryside. He increasingly turned to the latter for solace.

At the age of 13 he was apprenticed to an engraver. However, at 16 (in 1728) he left this trade to travel, but quickly become secretary and companion to Madame Louise de Warens. This relationship was unusual. Twelve years his senior she was in turns a mother figure, a friend and a lover. Under her patronage he developed a taste for music. He set himself up as a music teacher in Chambery (1732) and began a period of intense self education. In 1740 he worked as a tutor to the two sons of M. de Mably in Lyon. It was not a very successful experience (nor were his other episodes of tutoring).

In 1742 he moved to Paris. There he became a close friend of David Diderot, who was to commission him to write articles on music for the French Encyclopedie. Through the sponsorship of a number of society women he became the personal secretary to the French ambassador to Venice – a position from which he was quickly fired for not having the ability to put up with a boss whom he viewed as stupid and arrogant.

He returned to Paris in 1745 and earned a living as a music teacher and copyist. In the hotel where he was living (near the Sorbonne) he met Therese Lavasseur who worked as a seamstress. She was also, by a number of accounts, an odd figure. She was made fun of by many of those around here, and it was Rousseau’s defence of her that led to friendship. He believed she had a ‘pure and innocent heart’. They were soon living together (and they were to stay together, never officially married, until he died). She couldn’t read well, nor write, or add up – and Rousseau tried unsuccessfully over the years to teach her. According to his Confessions, Therese bore five children – all of whom were given to foundling homes (the first in 1746). Voltaire later scurrilously claimed that Rousseau had dumped them on the doorstep of the orphanage. In fact the picture was rather more complex. Rousseau had argued the children would get a better upbringing in such an institution than he could offer. They would not have to put up with the deviousness of ‘high society’. Furthermore, he claimed he lacked the money to bring them up properly. There was also the question of his and Therèse’s capacity to cope with child-rearing. Last, there is also some question as to whether all or any of the children were his (for example, Therèse had an affair with James Boswell whilst he stayed with Rousseau). What we do know is that in later life Rousseau sought to justify his actions concerning the children; declaring his sorrow about the way he had acted.

Diderot encouraged Rousseau to write and in 1750 he won first prize in an essay competition organized by the Academie de Dijon – Discours sur les sciences et les arts. ‘Why should we build our own happiness on the opinions of others, when we can find it in our own hearts?’ (1750: 29). In this essay we see a familiar theme: that humans are by nature good – and it is society’s institutions that corrupt them (Smith and Smith 1994: 184). The essay earned him considerable fame and he reacted against it. He seems to have fallen out with a number of his friends and the (high-society) people with whom he was expected to mix. This was a period of reappraisal. On a visit to Geneva reconverted to Calvinism (and gained Genevan citizenship). There was also a fairly public infatuation with Mme d’Houderot that with his other erratic behaviour, led some of his friends to consider him insane.

Rousseau’s mental health was a matter of some concern for the rest of his life. There were significant periods when he found it difficult to be in the company of others, when he believed himself to be the focus of hostility and duplicity (a feeling probably compounded by the fact that there was some truth in this). He frequently acted ‘oddly’ with sudden changes of mood. These ‘oscillations’ led to situations where he falsely accused others and behaved with scant respect for their humanity. There was something about what, and the way, he wrote and how he acted with others that contributed to his being on the receiving end of strong, and sometimes malicious, attacks by people like Voltaire. The ‘oscillations’ could also open up ‘another universe’ in which he could see the world in a different, and illuminating, way (see Grimsley 1969).

At around the time of the publication of his famous very influential discourses on inequality and political economy in Encyclopedie (1755), Rousseau also began to fall out with Diderot and the Encyclopedists. The Duke and Duchess of Luxembourg offered him (and Therèse) a house on their estate at Montmorency (to the north of Paris).

During the next four years in the relative seclusion of Montmorency, Rousseau produced three major works: The New Heloise (1761), probably the most widely read novel of his day); The Social Contract (April 1762), one of the most influential books on political theory; and Émile (May 1762), a classic statement of education. The ‘heretical’ discussion of religion in Émile caused Rousseau problems with the Church in France. The book was burned in a number of places. Within a month Rousseau had to leave France for Switzerland – but was unable to go to Geneva after his citizenship was revoked as a result of the furore over the book. He ended up in Berne. In 1766 he went to England (first to Chiswick then Wootton Hall near Ashbourne in Derbyshire, and later to Hume’s house in Buckingham Street, London) at the invitation of David Hume.

True to form he fell out with Hume, accusing him of disloyalty and displaying all the symptoms of paranoia. In 1767 he returned to France under a false name (Renou), although he had to wait until to 1770 to return officially. A condition of his return was his agreement not to publish his work. He continued writing, completing his Confessions and beginning private readings of it in 1770. He was banned from doing this by the police in 1771 following complaints by former friends such as Diderot and Madame d’Epinay – who featured in the work. The book was eventually published after his death in 1782.

Rousseau returned to copying music to make a living, working in the morning and walking and ‘botanizing’ in the afternoon. He continued to have mental health problems. His next major work was Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques, Dialogues, completed in 1776. In the next two years, before his death in 1778, Rousseau wrote the ten, classic, meditations of Reveries of the Solitary Walker. The book opens: ‘So now I am alone in the world, with no brother, neighbour or friend, nor any company left me but my own. The most sociable and loving of men has with unanimous accord been cast out by all the rest’. He appears to have come upon a period of some calm and serenity (France 1979: 9). At this time ‘he found respite only in solitude, the study of botany, and a romantically lyrical communion with nature’.

In 1778 he was in Ermenonville, just north of Paris, staying with the Marquis de Giradin.

On July 2, following his usual early morning walk he died of apoplexy (a haemorrhage – some of his former friends claimed he committed suicide).

Major Works of Jean Jacques Rousseau

– Discourse on Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences (1750)

– Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1755)

– The Social Contract (1762)

– Emile (1762)

– Letters Written from the Mount (1764)

– Confessions (1770)

Ideas

Ideas

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Great work!

Great info and right to the point. I don’t know if this is truly the best place to ask but do you folks have any ideea where to hire some professional writers? Thank you 🙂