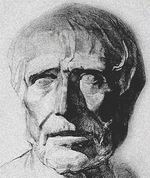

Lucretius was a Roman poet and the author of the philosophical epic De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of the Universe), a comprehensive exposition of the Epicurean world-view. Very little is known of the poet’s life, though a sense of his character and personality emerges vividly from his poem. The stress and tumult of his times stands in the background of his work and partly explains his personal attraction and commitment to Epicureanism, with its elevation of intellectual pleasure and tranquility of mind and its dim view of the world of social strife and political violence. His epic is presented in six books and undertakes a full and completely naturalistic explanation of the physical origin, structure, and destiny of the universe. Included in this presentation are theories of the atomic structure of matter and the emergence and evolution of life forms – ideas that would eventually form a crucial foundation and background for the development of western science. In addition to his literary and scientific influence, Lucretius has been a major source of inspiration for a wide range of modern philosophers, including Gassendi, Henri Bergson, Spencer, Whitehead, and Teilhard de Chardin.

Lucretius was a Roman poet and the author of the philosophical epic De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of the Universe), a comprehensive exposition of the Epicurean world-view. Very little is known of the poet’s life, though a sense of his character and personality emerges vividly from his poem. The stress and tumult of his times stands in the background of his work and partly explains his personal attraction and commitment to Epicureanism, with its elevation of intellectual pleasure and tranquility of mind and its dim view of the world of social strife and political violence. His epic is presented in six books and undertakes a full and completely naturalistic explanation of the physical origin, structure, and destiny of the universe. Included in this presentation are theories of the atomic structure of matter and the emergence and evolution of life forms – ideas that would eventually form a crucial foundation and background for the development of western science. In addition to his literary and scientific influence, Lucretius has been a major source of inspiration for a wide range of modern philosophers, including Gassendi, Henri Bergson, Spencer, Whitehead, and Teilhard de Chardin.

Of Lucretius’ life remarkably little is known: he was an accomplished poet; he lived during the first century BC; he was devoted to the teachings of Epicurus; and he apparently died before his magnum opus, De Rerum Natura, was completed. Almost everything else we (think we) know about this elusive figure is a matter of conjecture, rumor, legend, or gossip.

Some scholars have imagined that this lack of information is the result of a sinister plot – a conspiracy of silence supposedly conducted by pious Roman and early Christian writers bent on suppressing the poet’s anti-religious sentiments and materialist blasphemies. Yet perhaps more vexing for our understanding of Lucretius than any conspiracy of silence has been the single lurid item about his death that appears in a fourth century chronicle history by St. Jerome:

“94 BC. . . The poet Titus Lucretius is born. He was later driven mad by a love philtre and, having composed between bouts of insanity several books (which Cicero afterwards corrected), committed suicide at the age of 44.”

Certainly the possibility that Lucretius (whose blistering, two hundred line denunciation of sexual love comprises one of the memorable highlights of the poem) may himself have fallen victim to a love potion is a superb irony. Unfortunately, there is not a shred of evidence to support the claim. Nor is it highly likely that Cicero (a skeptical-minded thinker with sympathies toward Stoicism) would have assisted to any large degree in the publication of an epic celebrating the Epicurean creed. As for the suggestion that Lucretius produced De Rerum Natura in lucid periods between intervals of raging insanity, the poem itself stands as a strong argument to the contrary. At the very least it must be considered improbable that a work of such scope and complexity, of such intellectual depth and sustained reasoning power, could have been the product of fitful composition and a diseased mind.

Fortunately, even if we dismiss Jerome’s account as little more than an edifying fable and resign ourselves to the absence of even a scrap of reliable biographical information on Lucretius, there is still one source we can turn to for valuable insights into the poet’s character, personality, and habits of mind, and that is De Rerum Natura itself. For although the poem tells us almost nothing about the day to day affairs of Lucretius the man, it nevertheless furnishes a large and revealing portrait of Lucretius the poet, philosopher, social commentator, critic of religion, and observer of the world.

Indeed one does not have to read very far into the poem to discover that not only is Lucretius a serious student of philosophy and science, but that above all he is a great poet of nature. He reveals himself as a lover of woods, fields, streams, and open spaces, acutely sensitive to the beauties of landscape and the march of seasons. He proves a keen observer of plants and animals and at least as knowledgeable and interested in crops, weather, soil, and horticulture as in the existence of gods or the motion of atoms. The preponderance of natural descriptions and images in the poem has led some readers to suppose that the author must have led some form of rural existence, perhaps as the owner of a country estate. True or not, it is clearly not the city, with its hurly-burly of commerce, money grubbing, social climbing, and political strife, but the quiet countryside with its contemplative retreats, solitude, and simple pleasures that inspires his poetry and (as was the case with his master Epicurus in his garden at Athens) his philosophical reveries.

It is generally assumed that the poet, as his name implies, was a member of the aristocratic clan of the Lucretii. On the other hand, it is also possible that he was a former slave and freedman of that same noble family. Support for the idea of his nobility comes in part from his suave command of learning and the polished mastery of his style, but mostly from the easy and natural way (friend to friend, rather than subordinate to superior) in which he addresses Memmius, his literary patron and the addressee of the poem.

Gaius Memmius was a Roman patrician who was at one time married to Sulla’s daughter, Fausta. In 54 BC (one year after Lucretius’ death), he stood for consul, but was defeated owing to an electoral violation, which he himself revealed but was afterwards condemned for. In 52 BC he went into exile at Athens, and it is unknown whether he ever returned to Rome. Lucretius dedicated his poem to him, and throughout the epic the poet is at pains to remind Memmius of the sweet rewards of the Epicurean lifestyle and the bitter tribulations of public life. No doubt it would have distressed the poet deeply to know that his chief literary sponsor, instead of following the lofty path to Epicurean tranquilitas, ended his career with a vain descent into the tarnishing world of power politics and personal ambition.

Literary tradition has supplied Lucretius with a wife, Lucilla. However, except for a line or two in the poem suggesting the author’s personal familiarity with marital discord and the bedroom practices of “our Roman wives”, there is no evidence that he himself was ever married.

Major Works of Lucretius

– On the Nature of Things

I think this website has very superb indited articles blog posts.