Individualist rights-based feminist theory.

Women suffer principally because of the denial of their rights as individuals. The solution to their unequal treatment is the creation of true equality of rights, which is likely to be achieved by rational persuasion.

Source:

Z R Eisenstein, ed., The Radical Future of Liberal Feminism (New York, 1981)

Philosophy

Inherently pragmatic, liberal feminism does not have a clearly defined set of philosophies. Liberal feminists tend to focus on practical reforms of laws and policies in order to achieve equality; liberal feminism has a more individualistic approach to justice than left-wing branches of feminism such as socialist or radical feminism.[12] Susan Wendell argues that “liberal feminism is an historical tradition that grew out of liberalism, as can be seen very clearly in the work of such feminists as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, but feminists who took principles from that tradition have developed analyses and goals that go far beyond those of 18th and 19th century liberal feminists, and many feminists who have goals and strategies identified as liberal feminist […] reject major components of liberalism” in a modern or party-political sense; she highlights “equality of opportunity” as a defining feature of liberal feminism.[12]

Political liberalism gave feminism a familiar platform for convincing others that their reforms “could and should be incorporated into existing law”.[13] Liberal feminists argued that women, like men, be regarded as autonomous individuals, and likewise be accorded the rights of such.[13]

History

The goal for liberal feminists beginning in the late 18th century was to gain suffrage for women with the idea that this would allow them to gain individual liberty. They were concerned with gaining freedom through equality, diminishing men’s cruelty to women, and gaining opportunities to become full persons.[14] They believed that no government or custom should prohibit the due exercise of personal freedom. Early liberal feminists had to counter the assumption that only white men deserved to be full citizens. Pioneers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Judith Sargent Murray, and Frances Wright advocated for women’s full political inclusion.[14] In 1920, after nearly 50 years of intense activism, women were finally granted the right to vote and the right to hold public office in the United States, and in much of the Western world within a few decades before or a few decades after this time.

Liberal feminism was largely quiet in the United States for four decades after winning the vote. In the 1960s during the civil rights movement, liberal feminists drew parallels between systemic race discrimination and sex discrimination.[2] Groups such as the National Organization for Women, the National Women’s Political Caucus, and the Women’s Equity Action League were all created at that time to further women’s rights. In the U.S., these groups have worked, thus far unsuccessfully, for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment or “Constitutional Equity Amendment”, in the hopes it will ensure that men and women are treated as equals under the law. Specific issues important to liberal feminists include but are not limited to reproductive rights and abortion access, sexual harassment, voting, education, fair compensation for work, affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.[15]

Historically, liberal feminism, also called “bourgeois feminism”, was mainly contrasted with the working-class or “proletarian” women’s movements, that eventually developed into called socialist and Marxist feminism. Since the 1960s both liberal feminism and the “proletarian” or socialist/Marxist women’s movements are also contrasted with radical feminism. Liberal feminism is usually included as one of the two, three or four main traditions in the history of feminism.[16][5]

Individualist or libertarian feminism is sometimes grouped as one of many branches of feminism with historical roots in liberal feminism, but tends to diverge significantly from mainstream liberal feminism on many issues. For example, “libertarian feminism does not require social measures to reduce material inequality; in fact, it opposes such measures […] in contrast, liberal feminism may support such requirements and egalitarian versions of feminism insist on them.”[17] Unlike many libertarian feminists, mainstream liberal feminists oppose prostitution; for example the mainstream liberal Norwegian Association for Women’s Rights supports the ban on buying sexual services.[18]

Writers[edit]

Feminist writers associated with this theory include Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mill, Helen Taylor, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Gina Krog; Second Wave feminists Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Simone de Beauvoir; and Third Wave feminist Rebecca Walker.

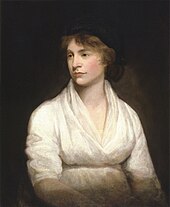

Mary Wollstonecraft

- Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) has been very influential in her writings as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman commented on society’s view of women and encouraged women to use their voices in making decisions separate from decisions previously made for them. Wollstonecraft “denied that women are, by nature, more pleasure seeking and pleasure giving than men. She reasoned that if they were confined to the same cages that trap women, men would develop the same flawed characters. What Wollstonecraft most wanted for women was personhood.”[2] She argued that patriarchal oppression is a form of slavery that could no longer be ignored[citation needed]. Wollstonecraft argued that the inequality between men and women existed due to the disparity between their educations. Along with Judith Sargent Murray and Frances Wright, Wollstonecraft was one of the first major advocates for women’s full inclusion in politics.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) was one of the most influential women in first wave feminism. An American social activist, she was instrumental in orchestrating the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention, which was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Not only was the suffragist movement important to Stanton, she also was involved in women’s parental and custody rights, divorce laws, birth control, employment and financial rights, among other issues.[19] Her partner in this movement was the equally influential Susan B. Anthony. Together, they fought for a linguistic shift in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to include “female”.[20] Additionally, in 1890 she founded the National American Woman Suffrage Association and presided as president until 1892.[20] She produced many speeches, resolutions, letters, calls, and petitions that fed the first wave and kept the spirit alive.[21] Furthermore, by gathering a large number of signatures, she aided the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act of 1848 which considered women legally independent of their husbands and granted them property of their own. Together these women formed what was known as the NWSA (National Women Suffrage Association), which focused on working legislatures and the courts to gain suffrage.

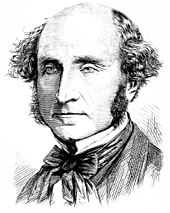

- John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (May 20, 1806 – May 8, 1873) believed that both sexes should have equal rights under the law and that “until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely.”[22] Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same “genuine unselfishness” that men did in providing for their families. This unselfishness Mill advocated is the one “that motivates people to take into account the good of society as well as the good of the individual person or small family unit”.[2] Similar to Mary Wollstonecraft, Mill compared sexual inequality to slavery, arguing that their husbands are often just as abusive as masters, and that a human being controls nearly every aspect of life for another human being. In his book The Subjection of Women, Mill argues that three major parts of women’s lives are hindering them: society and gender construction, education, and marriage.[23] He also argues that sex inequality is greatly inhibiting the progress of humanity.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.

This is a great tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere. Brief but very accurate info… Many thanks for sharing this one. A must read article!

I am very happy to read this. This is the type of manual that needs to be given and not the accidental misinformation that is at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this best doc.