Named after Swedish economist Erik Lindahl (1891-1960), Lindahl equilibrium theorizes that the provision of public goods reaches an equilibrium when everyone agrees on the level of goods to be provided, and their prices.

Thus, a set of Lindahl prices comprises individual shares of the collective tax burden of an economy. The sum of Lindahl prices is equal to the cost of supplying public goods.

Also see: scitovsky paradox, marginal cost pricing, social welfare function, compensation principle

History

The idea of using aggregate marginal utility in the analysis of public finance was not new in Europe. Knut Wicksell was one of the most prominent economists who studied this concept, eventually arguing that no individual should be forced to pay for any activity that does not give them utility.[2] Erik Lindahl was deeply influenced by Wicksell, who was his professor and mentor, and proposed a method for financing public goods in order to show that consensus politics is possible. As people are different in nature, their preferences are different, and consensus requires each individual to pay a somewhat different tax for every service, or good that he consumes. If each person’s tax price is set equal to the marginal benefits received at the ideal service level, each person is made better off by provision of the public good and may accordingly agree to have that service level provided.

Lindahl equilibrium

A Lindahl equilibrium is a state of economic equilibrium under a Lindahl tax as well as a method for finding the optimum level for the supply of public goods or services that happens when the total per-unit price paid by each individual equals the total per-unit cost of the public good. It can be shown that an equilibrium exists for different environments.[3] Therefore, the Lindahl equilibrium describes how efficiency can be sustained in an economy with personalized prices. Leif Johansen gave the complete interpretation of the concept of “Lindahl equilibrium”, which assumes that household consumption decisions are based on the share of the cost they must provide for the supply of the particular public good.[4]

This method of taxation for public goods is an equilibrium for two reasons. First, individuals are willing to pay the respective taxes for the quantity of public goods provided. Second, the cost of the public good is covered by the aggregate taxes. Therefore, the Lindahl pricing centers around the benefit principle, in which individuals are taxed based on their valuation of the benefit received from the good. This equilibrium is also the efficient level of public goods, as the social marginal benefit is equivalent to the social marginal cost.[5]

The importance of Lindahl equilibrium is that it fulfills the Samuelson condition and is therefore Pareto efficient,[3] despite the good in question being a public one. It also demonstrates how efficiency can be reached in an economy with public goods by the use of personalized prices. The personalized prices equate the individual valuation for a public good to the cost of the public good.[citation needed]

Lindahl Model

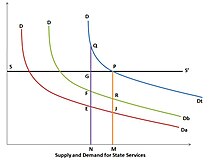

Lindahl’s Model of Taxation

In the Lindahl Model, Dt represents the aggregate marginal benefit curve, which is the sum of Da and Db—the marginal benefits for the two individuals in the economy. In a Lindahl equilibrium, the optimal quantity of the public good will be where the social marginal benefit intersects the marginal cost (point P). Each individual’s Lindahl tax rate will be based on their own marginal benefit curve. In this model, individual B will pay the price level at R and individual A will pay at point I.

Criticism

In theory, Lindahl pricing and taxation leads to an efficient provision of public goods. However, it requires the knowledge of the demand functions for each individual, and therefore is difficult to implement in practice. There are three main problems with the implementation of a Lindahl tax.

Preference revelation problem

When information about marginal benefits is available only from the individuals themselves, they tend to under report their valuation for a particular good. In doing this, an individual can lower his or her tax cost by under reporting the benefits derived from the public good or service. The incentive to lie is associated with the free rider problem; if an individual reports a lower benefit, he or she will pay less taxes, but only see a marginal decrease in the public good. This informational problem shows that survey-based Lindahl taxation is not incentive compatible. Incentives to understate or under report one’s true benefits under Lindahl taxation resemble those of a traditional public goods game.[5]

Preference revelation mechanisms can be used to solve that problem,[6][7] although none of these has been shown to completely and satisfactorily address it. The Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanism is an example of this, ensuring true values are revealed and that a public good is provided only when it should be. The allocation of cost is taken as given and the consumers will report their net benefits (benefits-cost) the public good will be provided if the sum of the net benefits of all consumers is positive. If the public good is provided side payments will be made reflecting the fact that truth telling is costly. The side payments internalize the net benefit of the public good to other players. The side payments must be financed from outside the mechanism. In reality, preference revelation is difficult as the size of the population makes it costly both in terms of money and time

Somebody essentially help to make severely articles I’d state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and to this point? I surprised with the analysis you made to make this actual publish amazing. Wonderful task!

Good info. Lucky me I recently found your blog by accident (stumbleupon). I have saved it for later.

very nice publish, i certainly love this web site, keep on it

Very good article! We are linking to this great content on our site. Keep up the great writing.