Theory of politics of Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-Tung) (1893-1976).

Adaption of Marxism and Stalinism to the conditions of China, in particular to guerrilla war in largely peasant societies.

It attempts to combine traditional Marxism with respect for the people and their ideas, as well as to abolish the profit motive in favor of moral incentives.

Source:

David Miller et al., eds, The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought (Oxford, 1987)

Origins

Modern Chinese intellectual traditionFurther information: Ideology of the Communist Party of China

At the turn of the 20th century, the contemporary Chinese intellectual tradition was defined by two central concepts: (i) iconoclasm and (ii) nationalism.[9]

Iconoclastic revolution and anti-Confucianism

By the turn of the 20th century, a proportionately small yet socially significant cross-section of China’s traditional elite (i.e. landlords and bureaucrats) found themselves increasingly skeptical of the efficacy and even the moral validity of Confucianism.[10] These skeptical iconoclasts formed a new segment of Chinese society, a modern intelligentsia whose arrival—or as historian of China Maurice Meisner would label it, their defection—heralded the beginning of the destruction of the gentry as a social class in China.[11]

The fall of the last imperial Chinese dynasty in 1911 marked the final failure of the Confucian moral order and it did much to make Confucianism synonymous with political and social conservatism in the minds of Chinese intellectuals. It was this association of conservatism and Confucianism which lent to the iconoclastic nature of Chinese intellectual thought during the first decades of the 20th century.[12]

Chinese iconoclasm was expressed most clearly and vociferously by Chen Duxiu during the New Culture Movement which occurred between 1915 and 1919.[12] Proposing the “total destruction of the traditions and values of the past”, the New Culture Movement was spearheaded by the New Youth, a periodical which was published by Chen Duxiu and was profoundly influential on the young Mao Zedong, whose first published work appeared on the magazine’s pages.[12]

Nationalism and the appeal of Marxism

Along with iconoclasm, radical anti-imperialism dominated the Chinese intellectual tradition and slowly evolved into a fierce nationalist fervor which influenced Mao’s philosophy immensely and was crucial in adapting Marxism to the Chinese model.[13] Vital to understanding Chinese nationalist sentiments of the time is the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed in 1919. The Treaty aroused a wave of bitter nationalist resentment in Chinese intellectuals as lands formerly ceded to Germany in Shandong were—without consultation with the Chinese—transferred to Japanese control rather than returned to Chinese sovereignty.[14]

The negative reaction culminated in the 4 May Incident in 1919 during which a protest began with 3,000 students in Beijing displaying their anger at the announcement of the Versailles Treaty’s concessions to Japan. The protest took a violent turn as protesters began attacking the homes and offices of ministers who were seen as cooperating with, or being in the direct pay of, the Japanese.[14] The 4 May Incident and Movement which followed “catalyzed the political awakening of a society which had long seemed inert and dormant”.[14]

Another international event would have a large impact not only on Mao, but also on the Chinese intelligentsia. The Russian Revolution elicited great interest among Chinese intellectuals, although socialist revolution in China was not considered a viable option until after the May 4 Incident.[15] Afterwards, “[t]o become a Marxist was one way for a Chinese intellectual to reject both the traditions of the Chinese past and Western domination of the Chinese present”.[15]

Yan’an period between November 1935 and March 1947

During the period immediately following the Long March, Mao and the Communist Party of China (CPC) were headquartered in Yan’an, which is a prefecture-level city in Shaanxi province. During this period, Mao clearly established himself as a Marxist theoretician and he produced the bulk of the works which would later be canonized into the “thought of Mao Zedong”.[16] The rudimentary philosophical base of Chinese Communist ideology is laid down in Mao’s numerous dialectical treatises and it was conveyed to newly recruited party members. This period truly established ideological independence from Moscow for Mao and the CPC.[16]

Although the Yan’an period did answer some of the questions, both ideological and theoretical, which were raised by the Chinese Communist Revolution, it left many of the crucial questions unresolved, including how the Communist Party of China was supposed to launch a socialist revolution while completely separated from the urban sphere.[16]

Mao Zedong’s intellectual development

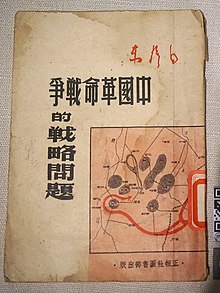

Strategic Issues of Anti-Japanese Guerrilla War (1938)

Mao’s intellectual development can be divided into five major periods, namely (1) the initial Marxist period from 1920–1926; (2) the formative Maoist period from 1927–1935; (3) the mature Maoist period from 1935–1940; (4) the Civil-War period from 1940–1949; and (5) the post-1949 period following the revolutionary victory.

Initial Marxist period (1920–1926)

Marxist thinking employs imminent socioeconomic explanations and Mao’s reasons were declarations of his enthusiasm. Mao did not believe that education alone would bring about the transition from capitalism to communism because of three main reasons. (1) Psychologically, the capitalists would not repent and turn towards communism on their own; (2) the rulers must be overthrown by the people; (3) “the proletarians are discontented, and a demand for communism has arisen and had already become a fact”.[17] These reasons do not provide socioeconomic explanations, which usually form the core of Marxist ideology.

Formative Maoist period (1927–1935)

In this period, Mao avoided all theoretical implications in his literature and employed a minimum of Marxist category thought. His writings in this period failed to elaborate what he meant by the “Marxist method of political and class analysis”.[18] Prior to this period, Mao was concerned with the dichotomy between knowledge and action. He was more concerned with the dichotomy between revolutionary ideology and counter-revolutionary objective conditions. There was more correlation drawn between China and the Soviet model.

Mature Maoist period (1935–1940)

Intellectually, this was Mao’s most fruitful time. The shift of orientation was apparent in his pamphlet Strategic Problems of China’s Revolutionary War (December 1936). This pamphlet tried to provide a theoretical veneer for his concern with revolutionary practice.[19] Mao started to separate from the Soviet model since it was not automatically applicable to China. China’s unique set of historical circumstances demanded a correspondingly unique application of Marxist theory, an application that would have to diverge from the Soviet approach.

Strategic Issues in the Chinese Revolutionary War (1947)

Civil War period (1940–1949)

Unlike the Mature period, this period was intellectually barren. Mao focused more on revolutionary practice and paid less attention to Marxist theory. He continued to emphasize theory as practice-oriented knowledge.[20] The biggest topic of theory he delved into was in connection with the Cheng Feng movement of 1942. It was here that Mao summarized the correlation between Marxist theory and Chinese practice: “The target is the Chinese revolution, the arrow is Marxism–Leninism. We Chinese communists seek this arrow for no other purpose than to hit the target of the Chinese revolution and the revolution of the east”.[20] The only new emphasis was Mao’s concern with two types of subjectivist deviation: (1) dogmatism, the excessive reliance upon abstract theory; (2) empiricism, excessive dependence on experience.

Post-Civil War period (1949–1976)

The victory of 1949 was to Mao a confirmation of theory and practice. “Optimism is the keynote to Mao’s intellectual orientation in the post-1949 period”.[21] Mao assertively revised theory to relate it to the new practice of socialist construction. These revisions are apparent in the 1951 version of On Contradiction. “In the 1930s, when Mao talked about contradiction, he meant the contradiction between subjective thought and objective reality. In Dialectal Materialism of 1940, he saw idealism and materialism as two possible correlations between subjective thought and objective reality. In the 1940s, he introduced no new elements into his understanding of the subject-object contradiction. In the 1951 version of On Contradiction, he saw contradiction as a universal principle underlying all processes of development, yet with each contradiction possessed of its own particularity”.[22]

Differences from Marxism

The two differences between Maoism and Marxism are how the proletariat are defined and what political and economic conditions would start a communist revolution:

- For Karl Marx, the proletariat were the urban working class, which was determined in the revolution by which the bourgeoisie overthrew feudalism.[23] For Mao Zedong, the proletariat were the millions of peasants, to whom he referred as the popular masses. Mao based his revolution upon the peasants because they possessed two qualities: (i) they were poor and (ii) they were a political blank slate; in Mao’s words, “[a] clean sheet of paper has no blotches, and so the newest and most beautiful words can be written on it”.[24]

- For Marx, the proletarian revolution was internally fueled by the capitalist mode of production; that as capitalism developed, “a tension arises between the productive forces and the mode of production”.[25] The political tension between the productive forces (the workers) and the owners of the means of production (the capitalists) would be an inevitable incentive to proletarian revolution which would result in a communist society as the main economic structure. Mao did not subscribe to Marx’s proposal of inevitable cyclicality in the economic system. His goal was to unify the Chinese nation and so realize progressive change for China in the form of communism; hence, revolution was needed as soon as possible. In The Great Union of the Popular Masses (1919), Mao said: “The decadence of the state, the sufferings of humanity, and the darkness of society have all reached an extreme”

Unquestionably imagine that that you said. Your favorite justification appeared to be on the web the easiest factor to bear in mind of. I say to you, I definitely get irked while other folks think about concerns that they just don’t realize about. You managed to hit the nail upon the highest and also outlined out the entire thing without having side-effects , other folks could take a signal. Will probably be again to get more. Thanks