A revival of the quantity theory of money, monetarism asserts that increases in the money supply cause inflation (‘too much money chasing too few goods’).

Monetarism emerged as an important economic doctrine under the influence of American economist Milton Friedman (1912-1992). Its adherents challenged the Keynesian approach to macroeconomics, emphasizing the importance of monetary policy in stabilizing the economy.

Laissez-faire is generally associated with monetarists, who avoid active manipulation of the economy by government. Believing that the money supply is the major determinant of nominal GNP, they tend to believe that fluctuations in the economy result from erratic growth in the money supply.

Also see: Thatcherism, Reaganomics, supply-side economics

Description

Monetarism is an economic theory that focuses on the macroeconomic effects of the supply of money and central banking. Formulated by Milton Friedman, it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently inflationary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining price stability.

This theory draws its roots from two historically antagonistic schools of thought: the hard money policies that dominated monetary thinking in the late 19th century, and the monetary theories of John Maynard Keynes, who, working in the inter-war period during the failure of the restored gold standard, proposed a demand-driven model for money.[4] While Keynes had focused on the stability of a currency’s value, with panics based on an insufficient money supply leading to the use of an alternate currency and collapse of the monetary system, Friedman focused on price stability.

The result was summarised in a historical analysis of monetary policy, Monetary History of the United States 1867–1960, which Friedman coauthored with Anna Schwartz. The book attributed inflation to excess money supply generated by a central bank. It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the money supply during a liquidity crunch.[5]

Friedman originally proposed a fixed monetary rule, called Friedman’s k-percent rule, where the money supply would be automatically increased by a fixed percentage per year. Under this rule, there would be no leeway for the central reserve bank, as money supply increases could be determined “by a computer”, and business could anticipate all money supply changes.[6][7] With other monetarists he believed that the active manipulation of the money supply or its growth rate is more likely to destabilise than stabilise the economy.

Opposition to the gold standard

Most monetarists oppose the gold standard. Friedman, for example, viewed a pure gold standard as impractical.[8] For example, whereas one of the benefits of the gold standard is that the intrinsic limitations to the growth of the money supply by the use of gold would prevent inflation, if the growth of population or increase in trade outpaces the money supply, there would be no way to counteract deflation and reduced liquidity (and any attendant recession) except for the mining of more gold.

Ris

Clark Warburton is credited with making the first solid empirical case for the monetarist interpretation of business fluctuations in a series of papers from 1945.[1]p. 493 Within mainstream economics, the rise of monetarism accelerated from Milton Friedman’s 1956 restatement of the quantity theory of money. Friedman argued that the demand for money could be described as depending on a small number of economic variables.[9]

Thus, where the money supply expanded, people would not simply wish to hold the extra money in idle money balances; i.e., if they were in equilibrium before the increase, they were already holding money balances to suit their requirements, and thus after the increase they would have money balances surplus to their requirements. These excess money balances would therefore be spent and hence aggregate demand would rise. Similarly, if the money supply were reduced people would want to replenish their holdings of money by reducing their spending. In this, Friedman challenged a simplification attributed to Keynes suggesting that “money does not matter.”[9] Thus the word ‘monetarist’ was coined.

The rise of the popularity of monetarism also picked up in political circles when Keynesian economics seemed unable to explain or cure the seemingly contradictory problems of rising unemployment and inflation in response to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1972 and the oil shocks of 1973. On the one hand, higher unemployment seemed to call for Keynesian reflation, but on the other hand rising inflation seemed to call for Keynesian disinflation.

In 1979, United States President Jimmy Carter appointed as Federal Reserve chief Paul Volcker, who made fighting inflation his primary objective, and who restricted the money supply (in accordance with the Friedman rule) to tame inflation in the economy. The result was a major rise in interest rates, not only in the United States; but worldwide. The “Volcker shock” continued from 1979 to the summer of 1982, decreasing inflation and increasing unemployment.[10]

By the time Margaret Thatcher, Leader of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, won the 1979 general election defeating the sitting Labour Government led by James Callaghan, the UK had endured several years of severe inflation, which was rarely below the 10% mark and by the time of the May 1979 general election, stood at 15.4%.[citation needed] Thatcher implemented monetarism as the weapon in her battle against inflation, and succeeded at reducing it to 4.6% by 1983. However, unemployment in the United Kingdom increased from 5.7% in 1979 to 12.2% in 1983, reaching 13.0% in 1982; starting with the first quarter of 1980, the UK economy contracted in terms of real gross domestic product for six straight quarters.[11]

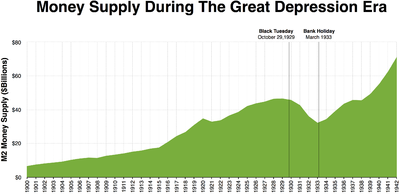

Money supply decreased significantly between Black Tuesday and the Bank Holiday in March 1933 in the wake of massive bank runs across the United States.

Monetarists not only sought to explain present problems; they also interpreted historical ones. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their book A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 argued that the Great Depression of the 1930s was caused by a massive contraction of the money supply (they deemed it “the Great Contraction”[12]), and not by the lack of investment Keynes had argued. They also maintained that post-war inflation was caused by an over-expansion of the money supply.

They made famous the assertion of monetarism that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Many Keynesian economists initially believed that the Keynesian vs. monetarist debate was solely about whether fiscal or monetary policy was the more effective tool of demand management. By the mid-1970s, however, the debate had moved on to other issues as monetarists began presenting a fundamental challenge to Keynesianism.

Monetarists argued that central banks sometimes caused major unexpected fluctuations in the money supply. They asserted that actively increasing demand through the central bank can have negative unintended consequences.

I went over this website and I think you have a lot of superb info, saved to bookmarks (:.