View that where one or more objects are of a certain kind or have a certain property, this is to be explained by postulating a non-material abstract entity to serve as a paradigm of which they are copies; in other words, universals (see Platonism) are to be regarded as (or replaced by) paradigms.

The term usually refers to one way of looking at Plato’s theory of forms, a way exemplified particularly by his Republic §§596a-7e and Timaeus 27d-29d, 48d-52d. It is this feature of Plato’s forms that seems to give rise to the third man argument.

Origins

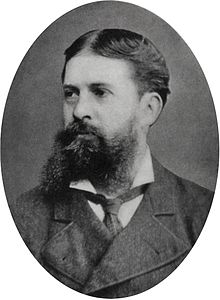

Charles Peirce: the American polymath who first identified pragmatism

Pragmatism as a philosophical movement began in the United States around 1870.[2] Charles Sanders Peirce (and his pragmatic maxim) is given credit for its development,[3] along with later 20th century contributors, William James and John Dewey.[4] Its direction was determined by The Metaphysical Club members Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and Chauncey Wright as well as John Dewey and George Herbert Mead.

The first use in print of the name pragmatism was in 1898 by James, who credited Peirce with coining the term during the early 1870s.[5] James regarded Peirce’s “Illustrations of the Logic of Science” series (including “The Fixation of Belief” (1877), and especially “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” (1878)) as the foundation of pragmatism.[6][7] Peirce in turn wrote in 1906[8] that Nicholas St. John Green had been instrumental by emphasizing the importance of applying Alexander Bain’s definition of belief, which was “that upon which a man is prepared to act”. Peirce wrote that “from this definition, pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary; so that I am disposed to think of him as the grandfather of pragmatism”. John Shook has said, “Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricism as an alternative to rationalistic speculation.”[9]

Peirce developed the idea that inquiry depends on real doubt, not mere verbal or hyperbolic doubt,[10] and said that, in order to understand a conception in a fruitful way, “Consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object”,[1] which he later called the pragmatic maxim. It equates any conception of an object to the general extent of the conceivable implications for informed practice of that object’s effects. This is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the generation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the employment and improvement of verification. Typical of Peirce is his concern with inference to explanatory hypotheses as outside the usual foundational alternative between deductivist rationalism and inductivist empiricism, although he was a mathematical logician and a founder of statistics.

Peirce lectured and further wrote on pragmatism to make clear his own interpretation. While framing a conception’s meaning in terms of conceivable tests, Peirce emphasized that, since a conception is general, its meaning, its intellectual purport, equates to its acceptance’s implications for general practice, rather than to any definite set of real effects (or test results); a conception’s clarified meaning points toward its conceivable verifications, but the outcomes are not meanings, but individual upshots. Peirce in 1905 coined the new name pragmaticism “for the precise purpose of expressing the original definition”,[11] saying that “all went happily” with James’s and F. C. S. Schiller’s variant uses of the old name “pragmatism” and that he nonetheless coined the new name because of the old name’s growing use in “literary journals, where it gets abused”. Yet in a 1906 manuscript, he cited as causes his differences with James and Schiller.[12] and, in a 1908 publication,[13] his differences with James as well as literary author Giovanni Papini. Peirce in any case regarded his views that truth is immutable and infinity is real, as being opposed by the other pragmatists, but he remained allied with them on other issues.[13]

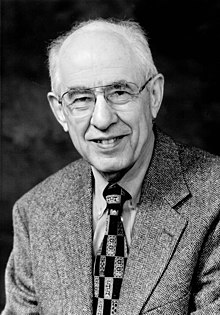

Pragmatism enjoyed renewed attention after Willard Van Orman Quine and Wilfrid Sellars used a revised pragmatism to criticize logical positivism in the 1960s. Inspired by the work of Quine and Sellars, a brand of pragmatism known sometimes as neopragmatism gained influence through Richard Rorty, the most influential of the late 20th century pragmatists along with Hilary Putnam and Robert Brandom. Contemporary pragmatism may be broadly divided into a strict analytic tradition and a “neo-classical” pragmatism (such as Susan Haack) that adheres to the work of Peirce, James, and Dewey.

Core tenets

A few of the various but often interrelated positions characteristic of philosophers working from a pragmatist approach include:

- Epistemology (justification): a coherentist theory of justification that rejects the claim that all knowledge and justified belief rest ultimately on a foundation of noninferential knowledge or justified belief. Coherentists hold that justification is solely a function of some relationship between beliefs, none of which are privileged beliefs in the way maintained by foundationalist theories of justification.

- Epistemology (truth): a deflationary or pragmatic theory of truth; the former is the epistemological claim that assertions that predicate truth of a statement do not attribute a property called truth to such a statement while the latter is the epistemological claim that assertions that predicate truth of a statement attribute the property of useful-to-believe to such a statement.

- Metaphysics: a pluralist view that there is more than one sound way to conceptualize the world and its content.

- Philosophy of science: an instrumentalist and scientific anti-realist view that a scientific concept or theory should be evaluated by how effectively it explains and predicts phenomena, as opposed to how accurately it describes objective reality.

- Philosophy of language: an anti-representationalist view that rejects analyzing the semantic meaning of propositions, mental states, and statements in terms of a correspondence or representational relationship and instead analyzes semantic meaning in terms of notions like dispositions to action, inferential relationships, and/or functional roles (e.g. behaviorism and inferentialism). Not to be confused with pragmatics, a sub-field of linguistics with no relation to philosophical pragmatism.

- Additionally, forms of empiricism, fallibilism, verificationism, and a Quinean naturalist metaphilosophy are all commonly elements of pragmatist philosophies. Many pragmatists are epistemological relativists and see this to be an important facet of their pragmatism (e.g. Joseph Margolis), but this is controversial and other pragmatists argue such relativism to be seriously misguided (e.g. Hilary Putnam, Susan Haack).

Anti-reification of concepts and theories

Dewey in The Quest for Certainty criticized what he called “the philosophical fallacy”: Philosophers often take categories (such as the mental and the physical) for granted because they don’t realize that these are nominal concepts that were invented to help solve specific problems.[14] This causes metaphysical and conceptual confusion. Various examples are the “ultimate Being” of Hegelian philosophers, the belief in a “realm of value”, the idea that logic, because it is an abstraction from concrete thought, has nothing to do with the action of concrete thinking.

David L. Hildebrand summarized the problem: “Perceptual inattention to the specific functions comprising inquiry led realists and idealists alike to formulate accounts of knowledge that project the products of extensive abstraction back onto experience.”[14]:40

Naturalism and anti-Cartesianism

From the outset, pragmatists wanted to reform philosophy and bring it more in line with the scientific method as they understood it. They argued that idealist and realist philosophy had a tendency to present human knowledge as something beyond what science could grasp. They held that these philosophies then resorted either to a phenomenology inspired by Kant or to correspondence theories of knowledge and truth.[citation needed] Pragmatists criticized the former for its a priorism, and the latter because it takes correspondence as an unanalyzable fact. Pragmatism instead tries to explain the relation between knower and known.

In 1868,[15] C.S. Peirce argued that there is no power of intuition in the sense of a cognition unconditioned by inference, and no power of introspection, intuitive or otherwise, and that awareness of an internal world is by hypothetical inference from external facts. Introspection and intuition were staple philosophical tools at least since Descartes. He argued that there is no absolutely first cognition in a cognitive process; such a process has its beginning but can always be analyzed into finer cognitive stages. That which we call introspection does not give privileged access to knowledge about the mind—the self is a concept that is derived from our interaction with the external world and not the other way around (De Waal 2005, pp. 7–10). At the same time he held persistently that pragmatism and epistemology in general could not be derived from principles of psychology understood as a special science:[16] what we do think is too different from what we should think; in his “Illustrations of the Logic of Science” series, Peirce formulated both pragmatism and principles of statistics as aspects of scientific method in general.[17] This is an important point of disagreement with most other pragmatists, who advocate a more thorough naturalism and psychologism.

Richard Rorty expanded on these and other arguments in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature in which he criticized attempts by many philosophers of science to carve out a space for epistemology that is entirely unrelated to—and sometimes thought of as superior to—the empirical sciences. W.V. Quine, instrumental in bringing naturalized epistemology back into favor with his essay “Epistemology Naturalized” (Quine 1969), also criticized “traditional” epistemology and its “Cartesian dream” of absolute certainty. The dream, he argued, was impossible in practice as well as misguided in theory, because it separates epistemology from scientific inquiry.

Hilary Putnam asserts that the combination of antiskepticism and fallibilism is a central feature of pragmatism.

Reconciliation of anti-skepticism and fallibilism

Hilary Putnam has suggested that the reconciliation of anti-skepticism[18] and fallibilism is the central goal of American pragmatism.[citation needed] Although all human knowledge is partial, with no ability to take a “God’s-eye-view”, this does not necessitate a globalized skeptical attitude, a radical philosophical skepticism (as distinguished from that which is called scientific skepticism). Peirce insisted that (1) in reasoning, there is the presupposition, and at least the hope,[19] that truth and the real are discoverable and would be discovered, sooner or later but still inevitably, by investigation taken far enough,[1] and (2) contrary to Descartes’ famous and influential methodology in the Meditations on First Philosophy, doubt cannot be feigned or created by verbal fiat to motivate fruitful inquiry, and much less can philosophy begin in universal doubt.[20] Doubt, like belief, requires justification. Genuine doubt irritates and inhibits, in the sense that belief is that upon which one is prepared to act.[1] It arises from confrontation with some specific recalcitrant matter of fact (which Dewey called a “situation”), which unsettles our belief in some specific proposition. Inquiry is then the rationally self-controlled process of attempting to return to a settled state of belief about the matter. Note that anti-skepticism is a reaction to modern academic skepticism in the wake of Descartes. The pragmatist insistence that all knowledge is tentative is quite congenial to the older skeptical tradition.

I like the helpful info you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your blog and check again here regularly. I am quite certain I’ll learn many new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

Hi there, You’ve done an excellent job. I will certainly digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I’m sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.|