A name first used by British critic and painter ROGER FRY (1886-1934) for artists of the same or next generation as the Impressionists, who rejected the latters’ preoccupation with surface effects of light and color.

Three artists – Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) – while benefiting from the technical achievements of the Impressionists and sharing their disdain for academic art, sought in highly individualistic ways to achieve greater order and harmony within their paintings, and to explore the expressive significance of subjects. Their work had great significance for all early 20th-century art movements.

The name loosely refers also to the work of GEORGES SEURAT (1859-1891) and neo-impressionism.

Post-Impressionism (also spelled Postimpressionism) is a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905, from the last Impressionist exhibition to the birth of Fauvism. Post-Impressionism emerged as a reaction against Impressionists’ concern for the naturalistic depiction of light and colour. Due to its broad emphasis on abstract qualities or symbolic content, Post-Impressionism encompasses Les Nabis, Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cloisonnism, Pont-Aven School, as well as Synthetism, along with some later Impressionists’ work. The movement was led by Paul Cézanne (known as the father of Post-Impressionism), Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Georges Seurat.[1]

The term Post-Impressionism was first used by art critic Roger Fry in 1906.[2][3] Critic Frank Rutter in a review of the Salon d’Automne published in Art News, 15 October 1910, described Othon Friesz as a “post-impressionist leader”; there was also an advert for the show The Post-Impressionists of France.[4] Three weeks later, Roger Fry used the term again when he organised the 1910 exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists, defining it as the development of French art since Manet.

Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued using vivid colours, often thick application of paint and real-life subject matter, but were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, distort form for expressive effect and use unnatural or arbitrary colour.

Overview

The Post-Impressionists were dissatisfied with what they felt was the triviality of subject matter and the loss of structure in Impressionist paintings, though they did not agree on the way forward. Georges Seurat and his followers concerned themselves with pointillism, the systematic use of tiny dots of colour. Paul Cézanne set out to restore a sense of order and structure to painting, to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums”.[5] He achieved this by reducing objects to their basic shapes while retaining the saturated colours of Impressionism. The Impressionist Camille Pissarro experimented with Neo-Impressionist ideas between the mid-1880s and the early 1890s. Discontented with what he referred to as romantic Impressionism, he investigated pointillism, which he called scientific Impressionism, before returning to a purer Impressionism in the last decade of his life.[6] Vincent van Gogh used colour and vibrant swirling brush strokes to convey his feelings and his state of mind.

Although they often exhibited together, Post-Impressionist artists were not in agreement concerning a cohesive movement. Yet, the abstract concerns of harmony and structural arrangement, in the work of all these artists, took precedence over naturalism. Artists such as Seurat adopted a meticulously scientific approach to colour and composition.[7]

Younger painters during the early 20th century worked in geographically disparate regions and in various stylistic categories, such as Fauvism and Cubism, breaking from Post-Impressionism.

Defining Post-Impressionism

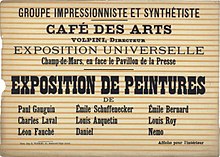

Poster of the 1889 Exhibition of Paintings by the Impressionist and Synthetist Group, at Café des Arts, known as The Volpini Exhibition, 1889

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Portrait of Émile Bernard, 1886, Tate Gallery London

The term was used in 1906,[2][3] and again in 1910 by Roger Fry in the title of an exhibition of modern French painters: Manet and the Post-Impressionists, organized by Fry for the Grafton Galleries in London.[7][8] Three weeks before Fry’s show, art critic Frank Rutter had put the term Post-Impressionist in print in Art News of 15 October 1910, during a review of the Salon d’Automne, where he described Othon Friesz as a “post-impressionist leader”; there was also an advert in the journal for the show The Post-Impressionists of France.[4]

Most of the artists in Fry’s exhibition were younger than the Impressionists. Fry later explained: “For purposes of convenience, it was necessary to give these artists a name, and I chose, as being the vaguest and most non-committal, the name of Post-Impressionism. This merely stated their position in time relatively to the Impressionist movement.”[9] John Rewald limited the scope to the years between 1886 and 1892 in his pioneering publication on Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin (1956). Rewald considered this a continuation of his 1946 study, History of Impressionism, and pointed out that a “subsequent volume dedicated to the second half of the post-impressionist period”:[10] Post-Impressionism: From Gauguin to Matisse, was to follow. This volume would extend the period covered to other artistic movements derived from Impressionism, though confined to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rewald focused on such outstanding early Post-Impressionists active in France as van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, and Redon. He explored their relationships as well as the artistic circles they frequented (or were in opposition to), including:

- Neo-Impressionism: ridiculed by contemporary art critics as well as artists as Pointillism; Seurat and Signac would have preferred other terms: Divisionism for example

- Cloisonnism: a short-lived term introduced in 1888 by the art critic Édouard Dujardin, was to promote the work of Louis Anquetin, and was later also applied to contemporary works of his friend Émile Bernard

- Synthetism: another short-lived term coined in 1889 to distinguish recent works of Gauguin and Bernard from that of more traditional Impressionists exhibiting with them at the Café Volpini.

- Pont-Aven School: implying little more than that the artists involved had been working for a while in Pont-Aven or elsewhere in Brittany.

- Symbolism: a term highly welcomed by vanguard critics in 1891, when Gauguin dropped Synthetism as soon as he was acclaimed to be the leader of Symbolism in painting.

Furthermore, in his introduction to Post-Impressionism, Rewald opted for a second volume featuring Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau “le Douanier”, Les Nabis and Cézanne as well as the Fauves, the young Picasso and Gauguin’s last trip to the South Seas; it was to expand the period covered at least into the first decade of the 20th century—yet this second volume remained unfinished.

Camille Pissarro, Haying at Eragny, 1889, Private Collection

Reviews and adjustments

Rewald wrote that “the term ‘Post-Impressionism’ is not a very precise one, though a very convenient one.” Convenient, when the term is by definition limited to French visual arts derived from Impressionism since 1886. Rewald’s approach to historical data was narrative rather than analytic, and beyond this point he believed it would be sufficient to “let the sources speak for themselves.”[10]

Rival terms like Modernism or Symbolism were never as easy to handle, for they covered literature, architecture and other arts as well, and they expanded to other countries.

- Modernism, thus, is now considered to be the central movement within international western civilization with its original roots in France, going back beyond the French Revolution to the Age of Enlightenment.

- Symbolism, however, is considered to be a concept which emerged a century later in France, and implied an individual approach. Local national traditions as well as individual settings therefore could stand side by side, and from the very beginning a broad variety of artists practicing some kind of symbolic imagery, ranged between extreme positions: The Nabis for example united to find synthesis of tradition and brand new form, while others kept to traditional, more or less academic forms, when they were looking for fresh contents: Symbolism is therefore often linked to fantastic, esoteric, erotic and other non-realist subject matter.

To meet the recent discussion, the connotations of the term ‘Post-Impressionism’ were challenged again: Alan Bowness and his collaborators expanded the period covered forward to 1914 and the beginning of World War I, but limited their approach widely on the 1890s to France. Other European countries are pushed back to standard connotations, and Eastern Europe is completely excluded.

So, while a split may be seen between classical ‘Impressionism’ and ‘Post-Impressionism’ in 1886, the end and the extent of ‘Post-Impressionism’ remains under discussion. For Bowness and his contributors as well as for Rewald, ‘Cubism’ was an absolutely fresh start, and so Cubism has been seen in France since the beginning, and later in England. Meanwhile, Eastern European artists, however, did not care so much for western traditions, and proceeded to manners of painting called abstract and suprematic—terms expanding far into the 20th century.

According to the present state of discussion, Post-Impressionism is a term best used within Rewald’s definition in a strictly historical manner, concentrating on French art between 1886 and 1914, and re-considering the altered positions of impressionist painters like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, and others—as well as all new schools and movements at the turn of the century: from Cloisonnism to Cubism. The declarations of war, in July/August 1914, indicate probably far more than the beginning of a World War—they signal a major break in European cultural history, too.

Along with general art history information given about “Post-Impressionism” works, there are many museums that offer additional history, information and gallery works, both online and in house, that can help viewers understand a deeper meaning of “Post-Impressionism” in terms of fine art and traditional art applications.

Post-Impression in specific countries

The Advent of Modernism: Post-impressionism and North American Art, 1900-1918 by Peter Morrin, Judith Zilczer, and William C. Agee, the catalogue for an exhibition at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta in 1986, gave a major overview of Post-Impressionism in North America.

Canada

Canadian Post-Impressionism is an offshoot of Post-Impressionism.[11] In 1913, the Art Association of Montreal’s Spring show included the work of Randolph Hewton, A. Y. Jackson and John Lyman: it was reviewed with sharp criticism by the Montreal Daily Witness and the Montreal Daily Star.[12] Post-Impressionism was extended to include a painting by Lyman, who had studied with Matisse.[13][14] Lyman wrote in defense of the term and defined it. He referred to the British show which he described as a great exhibition of modern art.[11]

Canadian artists and exhibitions

A wide and diverse variety of artists are called by this name in Canada, among them are James Wilson Morrice,[15] John Lyman,[16] David Milne,[17] and Tom Thomson,[18] members of the Group of Seven,[19] and Emily Carr.[20] In 2001, the Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa organized the traveling exhibition The Birth of the Modern: Post-Impressionism in Canada, 1900-1920.