1. Language games and power

Wittgenstein’s analysis of language games in his scattered texts, notably the Philo- sophical investigations (1972[1953]), was thin. Central and key concepts for thinking about language were introduced, including the notions of ‘form of life’ and ‘language game’, but were analytically underdeveloped. That this should be the case was hardly surprising given that many of the texts come from notes that his students took in his lectures, and were only constituted as books subsequent to his death in 1951. It was part of what made them so useful; that they were underdeveloped provided ample room for subsequent theorists to be creative (see, for instance, Pitkin 1972).

From the point of view of organization studies and the analysis of power, the most significant use of these key concepts remains the early work of Clegg (1975). Clegg, taking his cue from ethnomethodology but not using its conversation analysis approach, realized that the world of organizations is rich in discourse; whatever else managers may do, a large part of their work consists of the interpretation of key texts and the articulation and rationalization of different accounts of these. The research he conducted took as its empirical material audio tape recordings of naturally occur- ring conversations that were largely, but not entirely, framed by project meetings held on a construction site. In addition some of the data took the form of recordings of more consciously contrived interrogative interviews that he conducted.

Power came into the analysis in a way that blended Wittgenstein (1972[1953]) with Garfinkel (1967). One of the key concepts of the latter was the notion of ‘indexicality’, a term that originated from linguistics, where an indexical term would be defined as one that could only be understood in context. Classically indexical terms would be ‘it’ and ‘this’. For instance, in the following sentence one cannot know what either mean without an appropriate context being supplied: ‘It is this, then.’ It could be an interrogative or a factual statement referring to the rela- tion of two terms, but without a context being provided then the meaning of the terms is utterly inscrutable. One could as easily imagine the sentence to be one spoken by an explorer, a lover, or a politician, or, indeed, almost any identity.

What relates indexicality to power is context. In the context of construction sites the contract and its associated documents are the central framework shaping managerial discourse. The contract in question in Clegg’s (1975) research was of the kind that is referred to in the construction industry as a hard money contract, where the construction being undertaken was bid for on the basis of the specifica- tions in the contract, for a definite price, and where the most competitive tender won the contract. What this does is to set up a constitutive framework in which the meaning of the contract plays an essential role. Despite recommendations in the procedural handbooks of the industry, the contracts are never unindexical: they cannot be read simply as a precise and unequivocal set of instructions for building a building. There are at least two reasons for this, argued Clegg (1975). Both are questions of context – one immanently material to the conditions in which the specific contract is enacted and the other transcendentally constitutive of all contracts. The immanent reasons are simple. Contractual specifications, typically, are large and complex bodies of documentation. Not only are there the documents on which the work is bid but there is also an associated ‘bill of works’ comprising detailed consultants’ reports and associated documents. In an ideal world these would exist in an absolute and seamless correspondence of all detail from one document to another such that no document ever contradicted another or was in conflict with it. Given the vast amount of paper – comprising detailed specifications, reports, and projections – associated with relatively complex construction projects, that there actually is such correspondence is a large assumption to make. Many hands, at many times, with many distinct skills, produce the papers. More often than not there will be points of ambiguity or even disagreement between them. The precise meaning of them is not stipulated in the documents themselves. In Wittgenstein’s terms (1972[1953]) there is no meta-rule that provides the rules for how the mean- ing embedded in the documents should be interpreted. It is this that provides the immanent grounds for indexicality and substantial opportunity for extensive lan- guage games to be conducted between project managers and other significant actors on construction sites, such as consultant engineers, architects, and other managers and employees, in which the precise meaning of what is often imprecise documen- tation is translated into contested action.

A distinction between the ‘surface’ and the ‘deep’ structure is central to Wittgenstein’s thought. The classic case of the difference between surface and deep structure is one that Wittgenstein uses on several occasions and it involves the rela- tion between any given instances of speech and the idea of grammar. Speech is on the surface; it is what one hears or reads in a written form. Underlying it, however, are the rules of grammar. Unless speech is making no sense, because it is almost random in its utterances, the sense that is made must be one that occurs because there is a shared sense of grammar informing both speaker and hearer. Sharing does not necessarily mean agreement. One may understand only too well what the other is saying while disagreeing strongly with it. But the matter of agreement or disagreement is predicated on the fact that the rules that underlie the speech as sensible speech are shared. These rules comprise the deep structure of speech. They are such that any competent speaker/hearer/reader recognizes that they are in play and is thus able to make sense, but that does not mean that any such person could provide an adequate account of them. Formulating the rules is inordinately com- plex and something that only a skilled linguist is able to do properly. To do it labo- riously as one spoke or made sense would be absolutely inimical to sensemaking. It is this insight that underlies the whole of structural linguistics.

Wittgenstein thought of the deep structure in terms of grammar. Clegg argued that the texts that he recovered through audiotaping from the construction site had a social grammar underlying them, one that was embedded in their ‘form of life’, another Wittgensteinian concept. On some occasions of use the concept seems to mean no more than a mode of life; on other occasions the meaning is more inscrutable, possi- bly even genetically constitutive. It is with this concept that we begin to understand why the action should be contested, by reference to a transcendental framework.

Quite what Wittgenstein meant by form of life is not entirely clear. Clegg regarded the form of life as transcendentally constitutive and with this move brought together the surface structure and the deep structure. On the surface was what people said; underlying this was a deep structure of rules in the use of which people were more or less skilled game players, using a social grammar as a genera- tive device for making sense of what it was that was being said and what it was that could – and should – be said. Skill is the crucial issue in this regard, and the skills were basically a mastery of rhetoric, of being able to make something out of the opportunities presented by the contractual documents. Deeper still was a transcendental frame, the form of life, that made what was constituted by the grammar, the deep structure, sensible and rational, by stipulating the need for the organization to be as profitable an enterprise as it could be.

The action played out in specific arenas. Project meetings were the main arena. These meetings were held to discuss issues. Sometimes they had fairly formal agen- das, other times they were impromptu. Many of these were taped over a three-month period of intensive fieldwork. The issues invariably related some actions, or absence of actions, to the contractual documents contained in the bill of works. Thus, much of what was said in these meetings was said in relation to some putative but contested state of affairs in terms of the alignment of that state of affairs with the state that should have pertained in terms of the contractual specifications. The gap between these states was the matter at issue. Hence, the discourses involved attributions of responsibility for variance. What got to be said was spoken from different positions of material interest in the contract. For the head contractor the main issue was to find indexical particulars in the contract that could be exploited in order to win some contribution to the profitability of the site through processing variation orders for which additional payments could be demanded. The architect and client team sought to see that what they thought they had designed and were paying for was actually constructed for the price contracted. That is the point of a hard money contract: it is supposed to provide for a ‘what you contracted for is what you get at the price agreed’ outcome – at least in theory. In practice industry people know that skilled and shrewd project managers will find ways of creating significant and costly variance.

It can be seen that the rules underlying the surface production of text were quite clear; the project manager and his team sought systematically to exploit any index- icality in the contract in order to maximize profitability, while the architect and the client team sought to resist this at every turn. In turn, that these were the rules of the game only made sense in terms of a form of life of capitalism, in which the creation of profit was the fundamental aim.

To make it more concrete, the matter under discussion in a project meeting might be something apparently simple such as the meaning of clay. But while the meaning of clay may appear simple it soon becomes apparent that, from a perspective that sees the talk as exhibiting a surface structure, a deep structure, and a form of life, in fact the meaning is, precisely, a matter of power. The actually recorded material – what people said in situated action – provides the surface structure of the text. The contested matter was the depth of clay that should have been excavated to prepare the site for foundation pillars that were to be constructed out of poured concrete. The issue was simple. The consultant engineer’s drawings instructed excavation to a minimum of 600 mm into ‘sandy, stony clay’. They did not specify the depth at which such clay could be found. Accompanying the draw- ings were a series of reports from drilled test bore holes done as a site survey of the ground that had to be built on. These recommended excavation to a depth of two meters into clay. The project manager argued that there were different qualities of clay across the site, running at variable depths. There was ‘puddle clay’ and ‘sandy, stony clay’. He defined ‘normal clay’ as ‘sandy, stony clay’. The resulting depth of the excavations done became the subject of an acrimonious letter from the client’s archi- tect to the construction company. The points at issue resulted from investigation of the claimed excavation levels, which, as the letter put it, revealed little or no consistency. The counterclaim from the project manager was that the normal clay substrata varied in level across the site: hence the need for additional – and unauthorized – excavation. It was a complicated dispute, reported verbatim in Clegg (1975: Appendices 2 and 4) and commented on extensively in the text.

Table 10.1 Power, rule and domination: three dimensions of power

The analytical importance of the case is that it demonstrates that in everyday organizational life language games can be inherently political. First, the contesta- tion that occurs – the discourse of the site meetings – is not random. Second, contestation is patterned by the skillful use of the underlying rules for constitut- ing issues – searching for indexicality in the meaning of the documents – by the participants in the arena. These comprise a mode of rationality – a way of acting that is, within the situated action contest, rational. Third, this patterning only makes sense where the ultimate aim is the maximization of profit. We can repre- sent the analysis as in Table 10.1.

There are many other analyses of language games in Power, rule and domination (Clegg 1975) that apply the same model (which is later developed in Clegg 1979). The importance of the analysis is in showing how discourse can be looked at in terms of power relations that are focused neither merely on the hierarchical struc- turing of the organization nor on discourse as merely a set of floating signifiers. Signification is an essentially political – and profitable – business, as the text demonstrates. And fixing signification is a key element of power relations.

2. Foucault and the archeology of knowledge

As we discussed in Chapter 8, the work of Michel Foucault has had an important influence on thinking about power. In perhaps no area has he had more influence than in the development of discourse analysis. In a series of books that include History of sexuality (1990), Discipline and punish (1977), and Archeology of knowledge (1972), Foucault developed a complex and nuanced view of discourse. His ideas focused attention on the importance of discourse in the production of truth, the integral role of power in this process, and the role of discourse in social change (Fairclough 1992).

At the foundation of Foucault’s work is an insistence on the complete abandon- ment of correspondence theories of truth and on the necessity of moving discourse to the center of social analysis. The problem facing social investigation was not one of comprehending the truth behind the vagaries of the available texts but rather one of understanding how what was thought to be true at a moment and among a particular social group came to be thought of as true. The task facing anyone wanting to understand the dynamics of history and social change was one of understanding how things came to be true at a particular time and what other pos- sibilities existed; why what was said was said and what was not said was not said, and the effects that this had on the nature of truth, the patterns of power and priv- ilege, and the complex social structures that were thereby produced. It became an exercise in the archeology of knowledge as the nature of truth was followed back and the manner of its constitution revealed.

In order to understand Foucault’s approach it is useful to begin with the concept of discourse. Foucault defines discourses, or discursive formations, as bodies of knowledge that ‘systematically form the object of which they speak’ (1977: 49). At a fundamental level, discourse produces the social world to which it refers. Discourses retain a wide range of ‘socio-historically contingent linguistic, cultural, technical and organizational resources which actively constitute fields of knowl- edge and the practices they instantiate’ (Reed 1998: 195). In other words, discourses do not simply describe the social world; they constitute it by bringing certain phenomena into being through the way in which they categorize and make sense of an otherwise meaningless reality (Parker 1992).

Each discourse is defined by a set of rules or principles – the rules of formation – that lead to the appearance of particular objects through the categories and identities that make up recognizable social worlds. Discourse lays down the ‘conditions of possibility’ that determine what can be said, by whom, and when.

[Discourse] governs the way that a topic can be meaningfully talked about and reasoned about. It also influences how ideas are put into practice and used to regulate the conduct of others. Just as a discourse ‘rules in’ certain ways of talking about a topic, defining an acceptable and intelligible way to talk, write or conduct oneself, so also, by definition, it ‘rules out’, limits and restricts other ways of talking, of conducting our- selves in relation to the topic or constructing knowledge about it. (Hall 2001: 72)

Discourse ‘disciplines’ subjects in that actors are known – and know themselves – only within the confines of a particular discursive context and the possibility that that provides (Mumby 2001). Discourse thus influences individuals’ experiences and subjectivity, and their ability to think, speak and act, resulting in material effects in the form of practices and interactions, such that ‘language defines the possibili- ties of meaningful existence at the same time as it limits them’ (Clegg 1989: 151).

For Foucault, discourse – or at least the knowledge that it instantiates – is insep- arable from power. Power is embedded in knowledge and any knowledge system constitutes a system of power, as succinctly summarized in Foucault’s conception of ‘power/knowledge’. Knowledge, in the form of broad discourses, constitutes the building blocks of social systems in a profound and inescapable way. As Clegg explains, ‘the concern is with strategies of discursive power, where strategy appears as an effect of distinctive practices of power/knowledge gaining an ascendant posi- tion in the representation of normal subjectivity: forms of surveillance or psychia- try, for instance, which constitute the normal in respect to a penology or a medical knowledge from whose “gaze” and rulings no one can subsequently escape, whether prison or medical officer, or one carcerally or medically confined’ (1989: 152). In constructing the available identities, ideas and social objects, the context of power is formed: ‘it is in discourse that power and knowledge are joined together’ (Foucault 1990: 100).

The discursive conception of power ‘is not something that is acquired, seized, or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away; power is exercised from innumerable points, in the interplay of nonegalitarian relations’ (1990: 94). In other words, power is not something connected to agents but rather represents a complex web of relations determined by the systems of knowledge constituted in discourse.

Power is everywhere; not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere. And ‘Power,’ insofar as it is permanent, repetitious, inert and self- reproducing, is simply the over-all effect that emerges from all of these mobilities, the concatenation that rests on each of them and seeks in turn to arrest their movements. One needs to be nominalistic, no doubt: power is not an institution, and not a struc- ture; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attrib- utes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society. (1981: 93)

According to this view, power is embedded in a network of discourse that captures advantaged and disadvantaged alike in its web (Deetz 1992). Power is not a resource of a particular agent but a characteristic of discourse. Each situation has its own politics of truth, as the mechanisms that distinguish truth and falsehood and define knowledge vary according to the prevailing discourses (Foucault 1980). In every system of truth there is power and there can be no truth without systems of power to support it.

Foucault also rethought the relation between power and resistance. Just as power and knowledge are inextricably linked, so too are power and resistance. Resistance is never ‘in a position of exteriority in relation to power’ (Foucault 1990: 95). Therefore, where there is power there will also be resistance and, just as power is a broad and agentless web, resistance forms through a myriad of points distributed across webs of power/knowledge in an irregular, localized fashion. There is no centerpoint for resistance but, at every point where power is constituted through discourse, there is also resistance.

Foucault’s perspective emphasizes the fact that an actor is powerful only within a particular discursive context as it is discourse that creates the categories of power within which actors act. It is thus the discursive context, rather than the subjectivity of any individual actor, that influences the nature of political strategy. The politi- cal strategies that exist at a point in time depend fundamentally on the structures of power/knowledge with which the actor is embedded. In fact, for Foucault, the notion of agents acting purposefully in some way not determined by the discourse is antithetical. Discourse not only constructs the nature of social reality at a parti- cular point in time, but carries within it the blueprint for the future.

To the extent that meanings become fixed or reified in certain forms, which then artic- ulate particular practices, agents and relations, this fixity is power. Power is the appar- ent order of taken-for-granted categories of existence, as they are fixed and represented in a myriad of discursive forms and practices. (Clegg 1989: 183)

No statement occurs accidentally; no statement is unconnected to discourse. The task for the discourse analyst is to ask ‘how is it that one particular statement appeared rather than another?’ (Foucault 1972: 30). The structures of discursive formations form a cage within which only certain actions are possible and from which the direction of social and discursive change is determined. The nature of the discursive formation in place at any point in time is the source of power (and resistance), the social objects and identities, and the possibilities for speaking and acting, that exist at any point in time. Not only is the nature of the current relations of power determined by discourse, but so too is the future.

Foucault’s work has received a significant amount of attention and has had a wide-ranging influence on social science, as we saw in Chapter 8. At the same time, his work has been roundly criticized on at least two generic counts, in addition to the specific substantive criticisms already discussed in Chapter 8. First, his work (and even more the work of those influenced by him) has been criticized for being unnecessarily cryptic and verging on a ‘cult of obscurantism’ (Clegg 1989: 152). Although part of the explanation of this tendency lies in the fact that his work has been translated from French, it is clear from even a cursory look at any of his books that there is a grain of truth in this criticism. It is an aspect of his work that has had the dual effect of making it of great interest to a particular group of scholars for whom the obscurity was a source of delight while also ensuring, unfortunately, that his work had little impact on mainstream work within organization studies. There clearly remains a significant opportunity for exploring further the relevance of Foucault’s work for organization studies.

More importantly, Foucault’s work involves a relatively fatalistic view of power (Burman and Parker 1993), which has been criticized for its failure to recognize that power/knowledge discourses are an expression of strategies of control by identifi- able actors within a wider historical and institutional context. Critical discourse analysts, in particular, while sharing Foucault’s unique theoretical perspective, argue that his work lacks a sufficient sense of agency. This approach makes it difficult to investigate the role of dominant groups in producing systems of advantage and dis- advantage in society, let alone to introduce emancipatory interests. The concern with domination and emancipation is particularly clear in critical discourse analy- sis, to which we will now turn.

3. Critical discourse analysis

The work of Norman Fairclough (Fairclough 1992; Fairclough and Wodak 1997; Fairclough 2003; 2005) has been deeply influential in the development of a discursive approach to the study of organizations that he has termed critical discourse analysis (CDA). His work combines, in equal measures, a concern with the relation of discourse as social practice and social phenomena such as identity, social relations, and systems of belief and a concern with the relation of discourse as social practice and power. In doing so, he works to develop a perspective that connects close textual analysis with the social context in which the text occurs.

Fairclough’s work builds on a broad range of approaches that he argues attend to the linguistic nature of discourse but fail to deal with the social aspects, or provide an adequate attention to the social aspects of discourse, but gloss its tex- tual aspects. Researchers such as Sinclair and Coulthard (1975), Labov and Fanshel (1977) and Potter and Wetherell (1987) are given as examples of the first group. Their work focuses squarely on language but fails, from Fairclough’s point of view, to make the connection back to the social world. Their approaches provide impor- tant insight into the nature of linguistic practice, but fail to link that back signifi- cantly to the social world in which they occur. They are therefore of great interest in understanding the nature of meaningful interaction, but of much less interest in understanding how the social world is produced through this meaningful interac- tion. A singular focus on the micro-dynamics of language leaves them unable to make a significant contribution to more macro-level social theory.

The primary example of the second tradition, according to Fairclough, is Foucault, to whom he devotes significant attention in his earlier work. In his discussions of Foucault, he explores Foucault’s assertions regarding the connection between discourse and social reality (and in particular power). He sees Foucault as having much to say about the connection between broad sweeps of discourse and ideas such as social structure and the dynamics of social systems, but he also perceives a weakness in Foucault’s work in that it is unable to make the connection back to instances of language production. While Foucault provides extensive and interesting examples, he is unable to provide a framework for the systematic exam- ination of bodies of texts. His work stays at a very high level of abstraction and, while fascinating, is both impossible to replicate and very difficult to evaluate in terms of methodological rigor.

Fairclough’s own approach combines aspects of these two camps to develop what he calls ‘a synthesis of socially and linguistically oriented views of discourse, moving towards … a “social theory of discourse’’ ’ (1992: 5). At the heart of Fairclough’s framework is a highly theorized approach to discourse that allows him to connect more linguistically focused approaches to the broader social context that concerned Foucault.

Fairclough’s idea of discourse is based on conceptualizing ‘language use as a form of social practice’ (1992: 63). Two important ramifications follow. First, it means that discourse, as a form of social action, is constrained in important ways by social structure. What a certain actor can say at a particular time and place is limited by the social structures that exist at that moment. Social structure constrains discourse as a form of social action in just the same way as it constrains any other form of action. As Fairclough describes it, ‘discourse is shaped and constrained by social structure in the widest sense and at all levels, by class and other relations at a societal level, by relations specific to particular institutions such as law or education, by systems of classification, by various norms and conventions of both a discursive and non-discursive nature, and so forth’ (1992: 64).

At the same time, discourse as social practice is constitutive of the structures that constrain it. Social reality is, fundamentally, dependent on discourse as social action. It is through discourse as social practice that social structure is constituted. Discourse contributes to all of the levels of social structure that act back to constrain it as we described above. In other words, there is a complex and mutually constitutive relation between discourse and social structure.

It is also critical to keep in mind that discourse lies in the curious position of simultaneously stabilizing social relations and also functioning as a source of social change. It is through discourse that much of social structure is reproduced through discursive practices that reaffirm and re-enact social structure. But discourse can just as easily provide an arena for the struggles that lead to social change. Through discourse the social world is held in place and, equally, it is through discourse that it changes. Highlighting this complicated relation between discourse as a practice and the social structures that enable it provides the key to this form of discourse analysis and the point of entry for considerations of the role of discourse in the dynamics of power. Think of the way that George W. Bush used the rhetoric of old cowboy movies to articulate his opposition to Osama bin Laden and those who were alleged to support him: ‘Either you’re for us or you’re against us.’ It is a version of what has been referred to as the American Monomyth, in which the plot structure is always built around a superhero and a harmonious society threatened by evil forces (see Carlsen (2005: 47); also Jewett and Lawrence (1988)). It is through such positioning, which attempts to use identities familiar from hundreds of movies celebrating rugged individualism and straight shooting (preferably prior to asking questions and thus with a bias for action), that nodal points can be fixed discursively so that the parameters of power’s circuitry are stabilized through flows privileged by elite positioning.

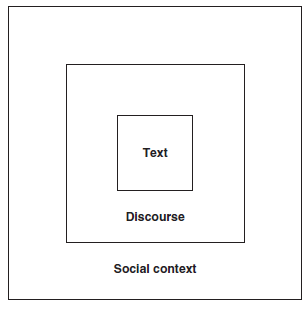

A particular understanding of the connection between text, discourse, and context grows out of this view of discourse and social structure and lies at the heart of Fairclough’s approach. His diagrammatic representation of his framework is shown in Figure 10.1. His explanation of the dynamics of his model is as follows:

It is an attempt to bring together three analytical traditions, each of which is indispens- able for discourse analysis. These are the tradition of close textual and linguistic analysis within linguistics, the macrosociological tradition of analysing social practice in relation to social structures, and the interpretivist or microsociological tradition of seeing social practice as something which people actively produce and make sense of on the basis of shared commonsense procedures. (1992: 72)

In other words, the deceptively simple framework shown in Figure 10.1 provides a comprehensive attempt to combine an interest in textual production with an interest in social structures through the addition of the concept of a discourse as both a collection of texts and the social practices through which they were produced, distrib- uted, and interpreted. The relation of discourse and social structure is dialectical and mutually constituting. At the same time discourse is both an object and a practice.

Figure 10.1 Fairclough’s three-dimensional conception of discourse

Building on this relationship between text, discourse, and social context, critical discourse analysts commonly argue for the constitution of three categories of social phenomena, as subjects, concepts, and objects. Subject positions are locations in social space from which certain delimited actors can produce certain kinds of texts in certain ways. Different subject positions are associated with different rights to produce new texts (Laclau and Mouffe 1985; Parker 1992). Some individuals, by virtue of their position in the discourse, will warrant a louder voice than others, while others may warrant no voice at all (Potter and Wetherell 1987). Subjects who have the right to produce texts, to engage in discursive practice, are therefore able to engage in the process of shaping concepts, objects, and subject positions (Hardy et al. 2000). For example, the discourse of psychiatry includes the subject position of the psychiatrist who has the right to produce texts, such as medical diagnoses, that determine the sanity of individuals. Collectively, psychiatrists produce texts, such as books, academic papers, radio and TV shows, that shape our understanding of concepts such as the unconscious. The psychiatric discourse also includes the subject position of mental patient, a position with radically fewer rights to engage in the discursive practices that can change or maintain the discourse. In other words, inhabiting certain subject positions affords actors a degree of agency in producing texts that may affect discourse. However, the kinds of texts that can be produced are often highly constrained. Texts that break ‘rules’ prescribed and made meaningful by prevailing discourses may result in actors losing the legitimate right to take up the subject position.

Discourse also produces sets of concepts – categories, relationships, and theories –through which we understand the world and relate to one another. Concepts make up what Harré (1995) refers to as the expressive sphere: the ideas that constitute our cultural background. From a discourse analysis point of view, concepts are all of the constructions that arise out of structured sets of texts and that exist solely in the realm of ideas. They are more or less contested, and are culturally and histori- cally situated; they are the fundamental ideas that underlie our understandings and relations with one another.

Concepts are historically contingent constructions that arise out of a discourse consisting of the texts produced, disseminated, and interpreted by a set of actors in a social situation. Concepts depend on the ongoing construction of texts for mean- ing and they may therefore change dramatically over time and from social group to social group. Since the meaning of a concept is dependent on discourse, and since individual understandings of the world depend on these concepts, participation in the discourse is political as discursive acts that succeed in transforming concepts change the world as it is understood. Discursive acts that are intended to redefine concepts are attempts to fashion preferable social relations and depend for their success on the resources available to the actor producing the text.

Finally, when concepts are brought into play to make sense of social relations or physical objects, then the discourse has constituted an object. Objects and concepts are obviously closely related. The primary difference lies in the fact that concepts exist only in the expressive sphere; they exist in the realm of ideas. Objects, on the other hand, are part of the practical order; they are real in the sense of existing in the material world. The concept of a ‘river’ exists in our minds as competent speakers of English. A particular river, say the River Thames that flows through London, is an object; it is made sensible to us by the concept ‘river’ and we can write about it using that same concept. But the river itself has a certain existence outside of the discourse that reveals it; it has an ontological reality beyond the discourse. It would continue to exist in a physical sense apart from our experience of it. Our deaths would not entail its disappearance as a material object, although it would necessitate its disappearance as ‘river’ as there would be no one left to attach that particular concept to it.

The role of discourse in constituting social objects is even more fundamental. The Thames flows without any awareness of the concept of a river. The Thames has no idea it is a river. In social objects, such as organizations, organizational members and others apply the concept of an organization to sets of material practices in a way that not only reveals the social nature of these practices and makes them meaningful (as in the Thames), but is fundamental to their performance. Changing the concept ‘river’, or convincing us that the Thames is actually a stream, may make us see it differently, but it does not change the nature of the Thames as a thing-in-itself. Changing the concept of an organization held by organizational members funda- mentally changes the way the organization is socially accomplished. The thing-in- itself changes as the practical applications of what it is and what it can do change.

Organizations and other social interactions depend on the discursive construc-tion of the underlying concepts and the discursive application of the concepts by members to make sense of their experience. By successfully modifying the discourse that underlies important concepts, and/or important objects, the actual accomplishments of social relationships can be changed. The act of creating and disseminating texts, of engaging in discursive practices, is therefore a highly political act and underlies the most fundamental struggle for power and control in organi- zations and in society more broadly. Underlying social reality is an intense struggle to determine the nature of constructs and to determine which construct applies in which case. The result is, not surprisingly, an ambiguous and contested set of dis- cursive structures full of contradiction and subject to continuous negotiations as to their meaning and application.

The resulting framework ‘provides a means of multi-functional analysis, attend- ing to the interplay between knowledge, social relations and social identity, and a means of historical analysis, allowing the analyst to trace the articulation of texts over time and the constitution of orders of discourse’ (Thomas 2003: 782). Even more importantly from our perspective, critical discourse analysis provides an approach to connecting the concern for language and discourse characteristic of the linguistic turn with a concern for power, domination, and ideology. It seeks to explore often opaque relationships of causality and determination between (a) discur- sive practices, events and texts, and (b) wider social and cultural structures, relations and processes; to investigate how such practices, events and texts arise out of and are ideologically shaped by relations of power and struggles over power; and to explore how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor secur- ing power and hegemony. (Fairclough 1993: 135)

Unsurprisingly, critical discourse analysis and related variants of discourse analysis play a major role in the discursive studies of organization. It is this development to which we will now turn.

Source: Clegg Stewart, Courpasson David, Phillips Nelson X. (2006), Power and Organizations, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1st edition.