It is not easy to categorise different types of unintended consequences and any kind of categorisation will have problems in locating some of them, for unin- tended consequences might come about in a variety of contexts and some of these contexts may be very complex. This section aims to develop a framework that makes the task of identifying different ‘unintended consequences’ easier and shows the subset to which the examples examined in this book belong. Although this account might have some limitations, it gives a better understanding of the explanations of unintended consequences of human action.

To begin with, we have to consider the possible methodological problems we may face in developing an account of a possible set of unintended consequences. As Merton (1936: 897) suggests when we start talking about unintended conse- quences, we are confronted with two possible methodological pitfalls. The first one is the ‘problem of ascertaining the extent to which “consequences” may justifiably be attributed to certain actions’. Simply to argue that unintended consequence X was caused by A’s intention to bring about Y, we need to know whether A’s action caused X or not. The simplest way to get a grip of this problem is to ask whether X would have occurred in the absence of A’s action. If the absence of A’s action prevents the consequence X, we may justifiably argue that X was an unintended consequence of A’s action, for A’s action was partially or fully responsible for X. Any satisfactory explanation of X as an unintended consequence has to provide a justifiable connection between A’s action and X. The second problem is ‘that of ascertaining the actual purposes of a given action’. That is, if we want to show that X is an unintended consequence of A’s action, we need to know the actual intention of A in doing Y, or we need to show that whatever A’s intention might be, it is not that of bringing about X. It is always problematic to talk about another person’s intentions, for we have no way of reading that person’s mind. Again, this is an important problem for any explanation of ‘unintended consequences’. However, these do not cause problems for our attempt to categorise unintended consequences, for in what follows we will be talking about possible types of un- intended consequences.

We may start our analysis of unintended consequences by distinguishing be- tween different levels, such as the social and the individual level. Then, we may consider the relation between the ‘target’ of the intention and the level on which the consequence is materialised. That is, we may examine spaces of materialisa- tion relative to the target of intentions. Let me introduce some examples to clarify what is meant by spaces of materialisation. If I break a vase in an attempt to kill a mosquito with a newspaper, the unintended consequence is materialised on a non-living object. If I were to miss the mosquito and strike my wife with the newspaper, then the unintended consequence is materialised on a human being. On the other hand, unintended consequences of the government tax plan would have larger and broader effects. Suffice it to say, unintended consequences would be materialised at the social level in contrast to the unintended consequences of my mosquito hunt. We may add to this that the nature of my intention in the mosquito hunt is different than government’s intentions. We may characterise this difference by saying that the target of the first intention is at the individual level, and the target of the second is at the social level.

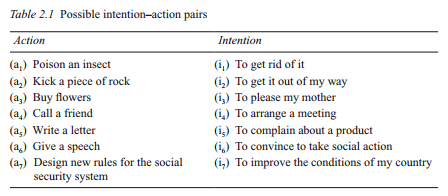

Let us start by thinking about the possible things one might be intending to do.5 Table 2.1 lists some possible intention–action pairs.

Out of the seven actions listed in Table 2.1 (a1–a7), (a1) and (a2) change the state of a physical object and (a3–a7) are about my relations with others. However, while I am concerned with myself when I am doing (a3), (a4) and (a5), I am trying to change something social when I am doing (a6) and (a7). Given the intentions, it is possible to divide these actions into two groups: ones that are about the state of the physical objects, animals, flowers, myself, any other person, etc., and others that are about the society partly or as a whole. For the first one, we can say that the intention is about the individual level (I), and for the second that the intention is about the social level (S).

We may also consider mixed intentions as a possibility. Suppose that you are able to change the rules of the social security system and you know that there is no effective monitoring or sanctioning mechanism for the abuse of this power (as might be observed in some of the underdeveloped countries). With this in mind, you may take your chance to change the rules of the social security system in order to improve your own social security, even though you also know that the new rules will have a bad influence on the whole social security system. If you do change these rules, we are confronted with a complex situation that is easy to classify: your intention is definitely about the individual level, but you are intend- ing to change something social as well. Here we have an example of an intention that is both about the individual level and social level (I + S) at the same time. It is not necessary that both intentions have equal weight. In this example, it is clear that the intention is more about the individual level than about the social level. (I+ S) captures the possible set of mixed combinations.

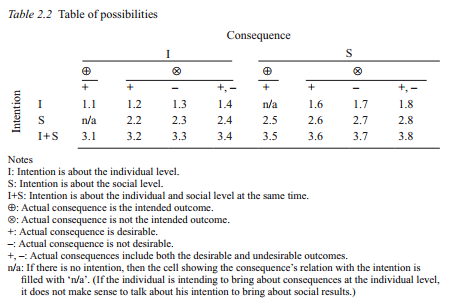

We have seen that intentions might be about different levels. Accordingly, con- sequences might be materialised at different levels. Like intentions, consequences may be at the individual or social level. Say that I want to clean my walking path (i2) and kick a piece of rock which is in my way (a2). If I am able to ‘move it away’, this is an intended consequence at the individual level (I ⊕). However, what appeared to be a small rock might be unmovable because it is actually a piece of a larger rock lying under the ground. In this case, my kicking might cause an injury to my foot. This is an unintended consequence at the individual level (I ⊗). Moreover, I might as well move the rock away and injure my foot at the same time. In this case, there are two consequences: the former intended and the latter unintended (I ⊕, ⊗). Now suppose that I am giving a speech (a6) to a crowd to convince them to vote against a new tax policy (a6). In this case, if I am able to convince them to vote against the new tax policy, this would be an intended consequence at the social level (S ⊕). Of course, there could also be unintended consequences at the social level (S ⊗).

We could also talk about these consequences with respect to their desirabil- ity. We may assume that the intended consequences are desirable, whatever we think about them. So, while moving the rock out of my path would be a desir- able (intended) consequence at the individual level (I +), hurting my foot would not be desirable (I –). If both of these things happen, I would have desirable and undesirable consequences at the same time. It is possible to talk about the social consequences in the same manner. Of course, talking about the desirability of the social outcome is not easy, but we are just trying to think about the possibilities.

Now we can gather the aforementioned possibilities to form a table of pos- sibilities (Table 2.2). For simplicity, this table takes into account only one individ- ual’s intentions and actions. Later, we will go on to discuss other possibilities for multiple individuals and for the cases where many individuals intend to achieve the same consequence.

Now let’s try to locate some of our examples in Table 2.2. Consider (i2) and (a2) above: the case where I kick the rock on my way to clear my walking path. Here, the intention is changing something at the individual level (row I). Thus, we are concerned only with the first row of the table. Now, if the consequence is that ‘the rock moved away’, it would be an intended consequence at the individual level (column I ⊕, +), which corresponds to cell 1.1 in Table 2.2. However, if I cannot move the rock away and hurt my foot in the process, this would be an undesirable unintended consequence, that is, cell 1.3 in Table 2.2. If I move the rock away and injure my foot at the same time then we would have one intended and one unintended consequence at the same time: a combination of cells 1.1 and 1.3 represents this situation. Similar examples may be given for other rows (i.e. for intentions about the social level and for mixed intentions) but this is not necessary for, by definition, the cells corresponding to the columns with unintended signs (⊗) indicate unintended consequences. Thus, out of twenty-four cells, eighteen denote unintended consequences.6 Broadly, there are three types of intentions that may bring about two types of unintended consequences. Any explanation or examination of unintended consequences should at least specify the type of intention and consequence in these terms.

Remember that Table 2.2 represents the possible set of unintended consequences for one individual. In the case that the actions of many individuals are involved in the generation of the unintended consequence, the set of possible unintended consequences expands. But, of course, we can represent other situations with this table. For example, if we are interested in unintended consequences of collective behaviour, we can interpret the table as representing the collective intentions of the people involved. These possibilities increase the number of possible types of unintended consequences. However, we need not reproduce the table including these cases. An understanding of the broadness of the notion is sufficient for our purposes. Neither the examples examined in this book nor the other examples in the relevant literature are about cases where collective intentionality exists or with cases where one individual’s actions bring about unintended social consequences (see Chapter 1). Roughly, in our examples, unintended consequences emerge out of the actions of multiple individuals whose intentions are targeted to the indi-vidual level. Since the above table represents only one individual’s intentions, we may interpret the rest of the individuals who are acting at the same time as a part of the environment within which the individual is acting. As in our example about the walking paths (see Chapter 1), in some cases other individuals’ actions are necessary for the consequence to come about. We will see more of this in the following section.

We may now tentatively tell the subject matter of this book. The examples in this book are explanations of the emergence of institutions or macro-social structures as the unintended consequences of intentional human action. In neither of these examples individuals intend to bring about a social consequence, or act collectively to bring about a social consequence.7 Generally, we are concerned with models that ‘explain’ the consequence at the social level as an unintended product of the intentions that are directed to the individual level. Thus, we are concerned only with the first row and with the right-hand side of Table 2.2. In Ta-ble 2.2, cells 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8 show the focus of these explanations relative to other possible unintended consequences. Thus, we are not concerned with unintended consequences of government intervention or with cases similar to the example that I unintendedly hurt my foot.8 The theory of spontaneous order, invisible-hand explanations and Menger’s so-called organic phenomena, are all concerned with cells 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8 in Table 2.2. However, this does not fully explicate what this book is really about, for Table 2.2 is concerned with one person’s intentions. The next section further specifies the characteristics of the type of unintended consequences we are concerned with.

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.