In order to examine the explanatory value of the chequerboard model we need to ask the following questions. First, is it necessary to conjecture about the indi- vidual mechanisms behind segregation and is this a good starting point for under- standing particular cases of residential segregation? Second, are the results of the chequerboard model applicable to the real world? Does the similarity between the chequerboard model and the real world (if any) allow us to carry the results of the model to the real world? Third, does the chequerboard model contribute in any way to our understanding of ethnically segregated neighbourhoods in the real world? Let us start seeking answers to these questions.

1. Postulating mechanisms

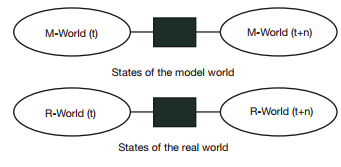

In Figure 4.4 M-World (t) depicts the chequerboard model’s initial state where there is no segregation. M-World (t + n) corresponds to the state of the chequer- board world with segregation. R-World (t) and R-World (t + n) illustrates the states of the real world (i.e. states of real world cities without and with segregation). Schelling demonstrates how M-World (t) can be transformed into M-World (t + n) through the interaction of individual mechanisms. The chequerboard model seems to be successful in showing this transformation for it contains a precise definition of the involved mechanisms. Remember that we have questioned the eligibility of Menger’s explanation for the model world for it did not contain such explicit mechanisms, only suggestions. Yet, although Schelling successfully demonstrates that even mild discriminatory preferences may lead to complete segregation in the chequerboard city, he does not explore all the possibilities in the model world. He does not argue, for example, that all initial distributions of agents (with different housing patterns and different number of agents) will lead to segregation in the chequerboard city, nor does he examine what would happen if the agents’ concep- tion of immediate neighbours is different. That is, it is not a logical necessity that mild discriminatory preferences bring about segregation under every condition in M-World (t). Thus, he only shows the possibility that mild discriminatory prefer- ences may cause segregation in the chequerboard city.

Figure 4.4 Model world and the real world.

The reader may have immediately observed that it is not likely to find a R- World (t) where different ethnic groups are distributed randomly as it is in M- World (t), because it is very unlikely that a real city becomes segregated starting from a point where different ethnic groups are randomly distributed. Rather, it is usually the case that a new ethnic group moves into the city at a point in time and the process of segregation gets started like this. As seen in Menger, M-World (t) rather represents an ideal starting point to investigate some of the mechanisms of segregation. The question is whether it is necessary to start from such an abstract world, or not.

The chequerboard model is an example of more general critical-mass models (Schelling 1978: 99). Critical-mass phenomena have the general property that people’s behaviour depends on how many others are behaving in a specific way: ‘What all the critical-mass models involve is some activity that is self-sustaining once the measure of that activity passes a certain minimum level’ (Schelling 1978: 95). In fact, the chequerboard model is a tipping model, a subclass of these critical-mass models. ‘Tipping is said to occur when some recognizable minority group in a neighbourhood reaches a size that motivates the other residents to begin leaving’ (Schelling 1972: 157). When some As start moving because they are unhappy, leaving some of the old residents unhappy, we can say that they are tipping out. Similarly, when some Bs move in and make some of the As unhappy enough to make them leave, they are tipping in. The tipping phenomenon was first described and illustrated by Morton Grodzins (1957) and Schelling examines the following question in his 1972 article: ‘how do we recognize tipping when we see it?’ As he argues, there are two options: one can either make a direct inquiry into the motives and expectations or look at the quantitative data on who moves in and who moves out. However, the first method gives us data – if it is reliable – about specific areas and it would be hard to find the mechanisms that can bring about segregation in this way.8 The latter data is about aggregate behaviour, so if there are different mechanisms that can produce the same aggregate behaviour, it would not enable us to say something about these mechanisms. Moreover, because dif- ferent people might have different tipping points (different preferences about liv- ing with the other group) it would be hard to find out a tipping point by looking at the aggregate data – because there might be none for a city (or a school, etc.) as a whole. If we are unable to see them from the aggregate data, how can we find these mechanisms? Schelling suggests that we should try different mechanisms and see if they work:

Rather than trying to infer from empirical data what mechanisms may be at work, we can postulate a mechanism and examine what results it would generate. If we can then verify the mechanism by the empirical identification of its components, we can use the model to explain and predict. Less ambi- tiously, we can compare the phenomena generated by the mechanism with what we observe, to see whether we can rule the mechanism out or establish its eligibility. Most likely of all, there may be some aspect of the mechanism that alerts us to certain phenomena, or helps to explain bits of what we ob- serve, and sharpens the concepts that guide further research.

(Schelling 1972: 159–160)

Finding out the causal mechanisms and structural relationships that produce the explanandum phenomenon is the key to a good explanation. The problem we sometimes face in our search for causal mechanisms is that of not being able to see it through the explanandum phenomenon. As early as 1843 Mill directed our attention to this problem with his distinction between ‘chemically composed’ causes and ‘mechanically composed’ causes. According to Mill, when causes combine ‘chemically’ the joint effect is not equal to the sum of the separate effects of the active causes.

The chemical composition of two substances produces, as it is well known, a third substance with properties entirely different from those of either of the two substances separately, or of both of them taken together. [. . .] We are not, at least in the present state of our knowledge, able to foresee what result will follow from any new combination, until we tried it by specific experiment.

(Mill 1843: 211, emphasis added)

In the case of chemical reaction, ‘the separate effects cease entirely and are succeeded by phenomena altogether different, and governed with different laws’ (Mill 1843: 254). Moreover, in this case it is not easy to find out the components (e.g. hydrogen and oxygen) of the resulting substance (e.g. water) by merely ob- serving it. Thus, Mill thinks that an inquiry into the chemically composed causes should be experimental10 for ‘every new case, stands in need of a new set of observations and experiments’ (Mill 1843: 144).

Some of the properties of residential segregation (s1, s2, . . . sn) have no coun- terpart at the individual level, and they are not reducible to the properties of the dispersed individuals (p1, p2, . . . pr). Moreover, aggregation of these individual properties does not give us the properties of residential segregation. The relation between (s1, s2, . . . sn) and (p1, p2, . . . pr) is somewhat similar to what Mill calls ‘chemical composition’ – although it would be totally misleading to think that segregation is similar to chemical substances, for it is governed by different causal mechanisms. If we look at the properties of the individuals, we cannot derive the properties of the aggregate phenomenon – and vice versa. But it does not follow from this that if we experiment with different combinations of individual agents (e.g. with different preferences), we cannot derive the properties of the resulting aggregate phenomenon. Thus, by experimenting with the individual mechanisms we may discover how the properties at the microlevel are connected to the proper-ties at the macrolevel.

Mill’s argument captures the very idea that we should try different combina- tions (experimental method, in Mill’s terminology) to understand the phenom- enon in hand. After all, if the system is complex and its properties do not provide enough information about the properties of its constituent parts, it is necessary to conduct experiments. Yet for the case of segregation, it is not easy to conduct an experiment in real cities. For this reason, Schelling states that ‘rather than trying to infer from empirical data what mechanisms may be at work, we can postulate a mechanism and examine what results it would generate’. Schelling is propos- ing a different experiment from what Mill could have thought. He is suggesting a thought experiment. Instead of experimenting with real cities and individuals, Schelling invites us to experiment within the model world to see how different micromotives can lead to the same social pattern of residential segregation. If material experiments are not feasible, it is a good idea to try different set-ups (ini- tial conditions, distribution of agents, etc.) and different mechanisms (different transition rules, preferences, etc.) to see which combinations are able to ‘produce’ the phenomenon in the model world. This is exactly what Schelling is doing. He shows us how properties of the dispersed individuals (p1, p2, . . . pr) are linked to the properties of residential segregation (s1, s2, . . . sn) by a social mechanism (by the network of individual IF . . . THEN rules), in the model world. Briefly, instead of examining the transformation of R-World (t) to R-World (t + n), Schell- ing conjectures about the possible mechanisms that may transform M-World (t) into M-World (t + n). Remember that Schelling asserts that ‘most likely of all, there may be some aspect of the mechanism that alerts us to certain phenomena, or helps to explain bits of what we observe, and sharpens the concepts that guide further research’. He may be interpreted as conceiving these conjectures as a start- ing point for explaining real phenomena and gaining insights about the possible ways in which R-World (t) may be transformed into R-World (t + n).

Sometimes, experimenting with different mechanisms (conjectures) may be a better starting point to understanding the nature of the phenomenon. Because of the complexity of the interactions among agents, conjecturing within the model world might be necessary to gain some knowledge, or at least insights about the real world. As with Menger’s case, we may use the analogy of explaining the origin of life to see the nature of Schelling’s contribution (see Chapter 3). The chequerboard model alerts us to a possible way in which certain individual mechanisms may interact and produce residential segregation. Stewart, some 200 years ago, defended a similar approach:

In examining the history of mankind, as well as in examining the phenomena of material world, when we can not trace the process by which an event has been produced, it is often of importance to be able to show how it may have been produced by natural causes.

(Stewart 1793 [1858]: 34, emphasis in original)

One of the most respected complexity theorists, John Holland, argues:

To build a competent theory one needs deep insights, not only to select a productive, rigorous framework (a set of mechanisms and constraints on their interactions), but also to conjecture about theorems that might be true (conjectures, say, about lever points that allow large, controlled changes in aggregate behaviour through limited local action).

(Holland 1998: 240, original italics deleted, emphasis added)

Yet how can we trust that these conjectures have any relevance for the real world? How can we jump from the mechanisms of segregation in the model world to the real causes of segregation?

2. Mechanisms and isolation

We have seen that Schelling thinks that it is not possible to discover some of the underlying causes of residential segregation by examining actual collective segregation – that is, by observing aggregate data concerning R-World (t + n). The argument is that it is not possible to draw inferences about the preferences of individuals by means of examining actual collective segregation. For this reason, Schelling suggests conjecturing about the individual motives that may lead to segregation. Evidently, residential segregation may emerge because of a variety of reasons. First, a group can organise itself in a way that every member acts consciously to prevent mixed neighbourhoods, and/or to move into places where no member of the other group exists, and/or to prevent others from entering into the housing market of their neighbourhood. Second, different groups might have different welfare and different living standards, and this may cause segregation.

Schelling writes:

Lines dividing the individually motivated, the collectively enforced, eco- nomically induced segregation are not clear lines at all. [. . .] They are further more not the only mechanisms of segregation. Separate or specialized com- munication systems – especially languages – can have a strong segregating influence.

(Schelling 1978: 139)

Note that he acknowledges that there might be many mechanisms acting togeth- er to bring about residential segregation. However, Schelling isolates his model from these factors and focuses on unorganised discriminatory behaviour. In other words, the aim of his models is to find out the kind of unorganised discriminatory behaviour that may lead to segregation.

Schelling (1972: 161) lists the following observations and insights concerning segregation:

- People live in cities which might have complex housing patterns and vaguely defined neighbourhoods.

- People have preferences about their neighbours and sometimes about their neighbourhood

- People have expectations about their neighbours and sometimes about their They also have expectations about the dynamics of their neighbours and sometimes about dynamics of their neighbourhood. This might affect the overall outcome.

- People might move in and out at different speeds and this might affect the overall outcome.

- There are potential other entrants to the city – e.g. new people from another place – and the population of the residents might change over time, which might affect the overall outcome.

However, the chequerboard model is isolated from most of these complexities of real life. For example, the chequerboard model employs the following isola- tions:

1′ People live in simple cities with no defined neighbourhoods.

2′ People have similar preferences about their neighbours, and they are not concerned about mixture of the neighbourhood, but the mixture of their immediate neighbours.

3′ People have no expectations.

4′ Speed is neglected.

5′ Potential other entrants are neglected.

Schelling focuses on one of the properties of the real individuals: that they may have a range of discriminatory preferences – that is from none to strong discrimi- nation – and he examines the type of discriminatory preferences that may lead to residential segregation. If we assume that the agents in the model do not care about the type of their neighbours, segregation does not occur unless the city is not already segregated. If they have strong discriminatory preferences – that is, if they want to be the majority in their neighbourhood – they get segregated. These results represent a possible state of affairs in the real world in a fair way. It seems to be true that strong discriminatory preferences would bring about segregation. Or, if individuals do not care about the type of their neighbours they would not be segregated given that there is no other reason (e.g. economic) that would separate them. Schelling’s chequerboard model points out another possibility; that agents with mild discriminatory preferences may cause segregation.

We may start assessing the chequerboard model by asking whether mild dis- criminatory preferences exist in the real world. We know that some individuals tend to avoid a minority status and need to belong to a certain group. It may even be argued that this tendency has some evolutionary roots. For example, it is commonly argued that the need to belong and tendency to live among a group increases the chances of survival (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Alexander 1974; Barchas 1986). Moreover, it has been argued that many individuals prefer to as- sociate themselves with what they consider to be their own kind (i.e. homophily12) (Bowles and Sethi 2006; McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook 2001; Tajfel et al. 1971). In brief, we may be pretty confident that mild discriminatory preferences exist in the real world. But do they cause segregation?

Sugden (2000: 23) argues that if we are to make inferences from the model world to the real world we must recognise some significant similarity between the model world and the real world. Schelling’s M-World (t) does not represent any real city in a faithful manner (more on this in Chapter 7). However, the individual mechanisms depicted in the model seem to represent real world tendencies. We do not know if this is a significant similarity but individual mechanisms that embody mild discriminatory preferences are similar to real world mechanisms. Maybe the only aspect of the chequerboard model that is familiar to us (i.e. represented in the model) is these individual mechanisms. In fact, it is due to the familiarity of the individual mechanisms presented in the model that we tend to think what happens in the chequerboard city may happen in the real world. This seems to be the only reason why we think that the possible ways in which the individual mechanisms interact in the model may be considered as possibilities for the real world.

The similarity between the chequerboard model and the real world is limited to some familiar individual mechanisms in isolation from others. We know that these mechanisms exist. We know that individuals have a tendency to avoid an extreme minority status. The chequerboard model alerts us to a possible aggregate mechanism: a possible way in which those individual mechanisms may interact in bringing about residential segregation. It is because of our knowledge of, and our familiarity with, these individual mechanisms that we consider the chequerboard model similar to the real world. The novelty of the chequerboard model comes from showing how these individual mechanisms may interact. Yet we cannot ac- cept the model, merely because it represents certain tendencies that we know about. The chequerboard model may be plausible and interesting, yet it does not tell us whether mild discriminatory preferences bring about segregation in the real world. It is just a thought experiment to illustrate the plausibility of this hy- pothesis.

Sugden (2000: 25) has one more suggestion about credibility: ‘Credibility in models is, I think, rather like credibility in “realistic” novels.’ Sugden is right here, at least to the extent that the model gives the account of the successive stages to explain the generation of the phenomenon in hand. Especially if the model is trying to explain the emergence or the origin of a phenomenon, credibility of a realistic novel might be required from an explanation. Gallie gives a very nice account and an example of this:

To follow a story – or a conversation, or a game, or the development and execution of a policy – involves for one thing some vague appreciation of its drift or direction, a vague sense of its alternative possible outcomes: but much more important for our purpose, it involves a relatively clear appreciation of certain relations of dependence of the sort that characteristically historical explanations serve to articulate [. . .] Consider, e.g., what we do when a child complains that he cannot follow the story we read aloud to him [. . .]. We re-read to the child the earlier stages of the story, or re-tell them in simpler language so as to emphasize those incidents which give sense or context to the present, puzzling episode. But in doing this we do not try to show that the present episode was a predictable consequence of earlier events, else the story would have been not un-followable, but unbearably dull as a story.

(Gallie 1955: 395)

If we consider Schelling’s account of the emergence of segregation as a story, we should appreciate its full credibility because simple but familiar behavioural rules bring about a surprising result: residential segregation emerges because of people who are trying to avoid a minority status. Moreover, successive stages of the story are clear and comprehensible, but not dull. Moreover, it encourages us to conjecture about other scenarios in order to see other possibilities. That is, we may grant Schelling’s model the status of a good story. This, of course, adds to its credibility but the main reason why we feel that the story may have some relevance for the real world is our familiarity with the suggested mechanisms. We conceive the states of the chequerboard model as possible states of the real world because of this familiarity. It is, in this sense, that Schelling’s explanation is cred- ible like a realistic novel. Moreover, because it examines the interaction of some known mechanisms, it is more than a ‘conceptual exploration’ (Sugden 2000: 11, cf. Hausman 1992). Despite its deficiencies, it is a theoretical explanation that alerts us to certain possibilities in the real world. More properly, it is a partial potential theoretical explanation.

3. Explanatory breath

Note that some authors suggest that ‘Schelling is presenting a critique of a com- monly held view that segregation must be the product either of deliberate public policy or of strongly segregationist [i.e., discriminatory] preferences’ (Sugden 2000: 9). Of course, Schelling’s model might be able to convince us about the weakness of the explanations that explain segregation either by organised action or by strong discriminatory preferences. However, Schelling thinks that there might be several different causes of residential segregation. But he does not focus on these aspects of segregation, rather he shows another possibility. In fact, the chequerboard model does not seem to contradict other theories about residential segregation; it is consistent and coherent with the existing body of knowledge about residential segregation. To see this, let us assume that we have a meta-mod- el or theory (i.e. a collection of models) of residential segregation that combines Schelling’s model and the other models (or explanations) of residential segrega- tion. According to this meta-model, near to complete segregation will emerge if the following conditions exist separately or in different combinations:

- If agents have strong (or milder) discriminatory preferences and if they collectively or separately intend to prevent a mixed neighbourhood.

- If agents have strong (or milder) discriminatory preferences (about the neighbourhood or about their immediate neighbours) and if they intend to live in a place where they can be content, but have no intention to change the mixture of the neighbourhood.

- If there are other forces (e.g. economic) preventing the two different groups to live in (move to, etc.) close places.

It is generally accepted that other things being equal, we should prefer a model that explains more than the alternative hypotheses (e.g. Thagard 1992: 74). Con- sider the meta-model before Schelling. It asserts that strong discriminatory prefer- ences, organised action and economic processes are the main causes of residential segregation. Schelling’s contributions change the existing meta-model by adding one more explanatory factor to it. Thus, Schelling’s contribution improves the explanatory breadth of the meta-model. Or to put it differently, the new meta- model has more applicability. Schelling’s model extends our understanding of residential segregation and gives us extra tools to explain particular instances of residential segregation. Thus, we may interpret Schelling as stating that ‘if you want to explain residential segregation in Rotterdam, you should search for organised action, economic factors (such as welfare differences among different ethnic groups) and mild segregationist preferences. Then you should use the ap- propriate tools to see whether any of these causes exist in Rotterdam.’ The good thing about Schelling’s model is that it makes us aware of the fact that any of these causes (or any combination of these causes) may lead to residential segregation. The chequerboard model does not readily improve our understanding of particu- lar cases of segregation, yet opens our eyes to a new explanatory factor which may explain segregation. Moreover, even in cases where economic factors and/ or organised action are the main causes of segregation, the mechanisms proposed by Schelling may have some relevance. For example, suppose that individuals with strong discriminatory preferences are organised in a way to prevent mixed neighbourhoods. Some As are intentionally forming isolated neighbourhoods. Yet not everyone in the city would be likely to join this organised action. Some of them would have weaker discriminatory preferences. Yet when the number of As in their neighbourhood decreases to a level they would not tolerate, they may consider moving out. In this example, the mechanisms proposed by Schelling are not the main explanatory factors in explaining the resulting residential segrega- tion, yet if we can confirm the existence of these mechanisms they would provide a deeper understanding of this case.

To understand how Schelling’s models changed our understanding, we can also think in the following way: previous theories of segregation assumed a linear relation between segregation and the strength of the discriminatory preferences. Schelling argued that the relation is not linear. For example, up to a point within the range of possible preferences – from no discriminatory preferences to mild discriminatory preferences (e.g. tolerant to 25 per cent minority status) – we do not observe segregation. However, after that point – from mild discriminatory preferences to very strong ones – segregation emerges, that is, there is a transi- tion.13 Thus, Schelling’s models, without any contradictory statements about the causes of segregation, improves upon previous models by incorporating a wider range of possible types of preferences.

Source: Aydinonat N. Emrah (2008), The Invisible Hand in Economics: How Economists Explain Unintended Social Consequences, Routledge; 1st edition.