The early classical economists believed that profits would eventually decline.

The Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) viewed the growth rate of capital accumulation (which took place at a rate higher than total output) as the cause.

The English economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) argued that a decline in the general rate of profit was caused by the diminishing marginal productivity of land.

The German political economist Karl Marx (1818-1883) believed that the rate of profit was influenced by the growth of competition between capitalists.

Source:

A Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (London, 1776);

D Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (London, 1817);

K Marx, Capital, i-ni (Harmondsworth, ,1976-81)

Competitive and contestable markets

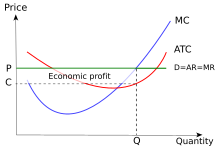

Only in the short run can a firm in a perfectly competitive market make an economic profit.

Economic profit does not occur in a perfectly competitive market once it has reached a long run equilibrium. If an economic profit was available, there would be an incentive for new firms to enter the industry, aided by a lack of barriers to entry, until it no longer existed.[4] When new firms enter the market, the overall supply increases. Furthermore, these intruders are forced to offer their product at a lower price to entice consumers to buy the additional supply they have created and to compete with the incumbent firms (see Monopoly profit § Persistence).[7][8][9][10] As the incumbent firms within the industry face losing their existing customers to the new entrants, they are also forced to reduce their prices.

An individual firm can only produce at its aggregate production function. Which is a calculation of possible outputs and given inputs; such as capital and labour. New firms will continue to enter the market until the price of the product is lowered to equal the average cost of producing the product.[7][8] Once this has occurred a perfect competition exists and economic profit is no longer available.[11] When this occurs, economic agents outside the industry find no advantage to entering the market, as there is no economic profit to be gained. Therefore, the supply of the product stops increasing, and the price charged for the product stabilizes, settling into an equilibrium.[7][8][9]

The same is likewise true of the long run equilibria of monopolistically competitive industries, and more generally any market which is held to be contestable. Normally, a firm that introduces a differentiated product can initially secure temporary market power for a short while (See Monopoly Profit § Persistence). At this stage, the initial price the consumer must pay for the product is high, and the demand for, as well as the availability of the product in the market, will be limited. In the long run however, when the profitability of the product is well established, and because there are few barriers to entry,[7][8][9] the number of firms that produce this product will increase. Eventually, the supply of the product will become relatively large, and the price of the product will reduce to the level of the average cost of production. When this finally occurs, all economic profit associated with producing and selling the product disappears, and the initial monopoly turns into a competitive industry.[7][8][9] In the case of contestable markets, the cycle is often ended with the departure of the former “hit and run” entrants to the market, returning the industry to its previous state, just with a lower price and no economic profit for the incumbent firms.

Economic profit can, however, occur in competitive and contestable markets in the short run, as a result of firms jostling for market position. Once risk is accounted for, long-lasting economic profit in a competitive market is thus viewed as the result of constant cost-cutting and performance improvement ahead of industry competitors, allowing costs to be below the market-set price.

Uncompetitive markets

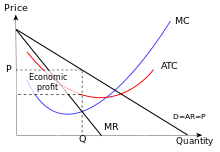

A monopolist can set a price in excess of costs, making an economic profit (shaded). The above picture shows a monopolist (only one firm in the industry/market) that obtains a (monopoly) economic profit. An oligopoly usually has “economic profit” also, but usually faces an industry/market with more than just one firm (they must share available demand at the market price).

Economic profit is much more prevalent in uncompetitive markets such as in a perfect monopoly or oligopoly situation. In these scenarios, individual firms have some element of market power. Although monopolists are constrained by consumer demand, they are not price takers, but instead either price or quantity setters. This allows the firm to set a price which is higher than that which would be found in a similar but more competitive industry, allowing the firms to maintain an economic profit in both the short and long run.[7][8]

The existence of economic profits depends on the prevalence of barriers to entry: these stop other firms from entering into the industry and sapping away profits,[10] like they would in a more competitive market. To understand the barriers, see them as certain fixed cost a firm must pay to enter into the market. Other examples of barriers include; patents, land rights and certain zoning laws.[2] These barriers allow firms to maintain a large portion of market share as new entrants are unable to obtain the necessary requirements or pay the initial costs of entry.

An Oligopoly is a case where barriers are present, but more than one firm is able to maintain the majority of the market share. In an Oligopoly firms are able to collude and their limit production, thereby restricting supply and maintaining a constant economic profit.[7][10][1] An extreme case of an uncompetitive market is a monopoly, where only one firm has the ability to supply a good which has no close substitutes.[2] In this case, the monopolist can set its price at any level it desires, maintaining a substantial economic profit. In both scenarios firms are able to maintain an economic profit by setting prices well above the costs of production, receiving an income that is significantly more than its implicit and explicit costs.

Government intervention

The existence of uncompetitive markets such as; monopolies and oligopolies, puts consumers at risk of paying substantially higher prices for a lower quality product.[12] As Monopolists and Oligopolists hold large portions of the market share, there is a smaller significance placed consumer demands when compared to a perfectly competitive market, especially if the good provided has an inelastic demand. Due to this, governments must intervene in uncompetitive markets, in an attempt to raise the number of firms in the industry, and therefore reduce prices and increase the overall quality for consumers.

In a regulated industry, the government examines firms’ marginal cost structure and allows them to charge a price that is no greater than this marginal cost. This does not necessarily ensure zero economic profit for the firm, but eliminates a monopoly profit.

Competition laws were created to prevent powerful firms from using their economic power to artificially create barriers to entry in an attempt to protect their economic profits.[8][9][10] This includes the use of predatory pricing toward smaller competitors.[7][10][1] For example, in the United States, Microsoft Corporation was initially convicted of breaking Anti-Trust Law and engaging in anti-competitive behaviour in order to form one such barrier in United States v. Microsoft. After a successful appeal on technical grounds, Microsoft agreed to a settlement with the Department of Justice in which they were faced with stringent oversight procedures and explicit requirements[13] designed to prevent this predatory behaviour. With lower barriers, new firms can enter into the market again, making the long run equilibrium much more like that of a competitive industry, with no economic profit for firms and more reasonable prices for consumers.

On the other hand, if a government feels it is impractical to have a competitive market – such as in the case of a natural monopoly – it will allow a monopolistic market to occur. The government will regulate the existing uncompetitive market and control the price the firms charge for their product.[8][9] For example, the old AT&T (regulated) monopoly, which existed before the courts ordered its breakup, had to get government approval to raise its prices. The government examined the monopoly’s costs, and determined whether or not the monopoly should be able raise its price. If the government felt that the cost did not justify a higher price, it rejected the monopoly’s application for a higher price. Though a regulated firm will not have an economic profit as large as it would in an unregulated situation, it can still make profits well above a competitive firm in a truly competitive market.

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all of us you really know what you’re talking about! Bookmarked. Please also visit my web site =). We could have a link exchange contract between us!

Hello! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My weblog looks weird when viewing from my apple iphone. I’m trying to find a template or plugin that might be able to correct this issue. If you have any recommendations, please share. Thanks!

Its like you read my thoughts! You appear to grasp a lot about this, like you wrote the ebook in it or something. I think that you simply can do with some p.c. to force the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this is great blog. A fantastic read. I’ll certainly be back.|

Very good information. Lucky me I ran across your blog by chance (stumbleupon). I’ve book marked it for later!