Yoga (/ˈjoʊ.ɡə/ (![]() listen);[1] Sanskrit: योग, lit. ‘yoke’ or ‘union’ pronounced [joːɡɐ]) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated in ancient India, aimed at controlling (‘yoking’) and stilling the mind, and recognizing the detached ‘witness-consciousness’ as untouched by the activities of the mind (Citta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There are a broad variety of the schools of yoga, practices, and goals[2] in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism,[3][4][5] and traditional forms and modern methods of yoga are practiced worldwide.[6]

listen);[1] Sanskrit: योग, lit. ‘yoke’ or ‘union’ pronounced [joːɡɐ]) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated in ancient India, aimed at controlling (‘yoking’) and stilling the mind, and recognizing the detached ‘witness-consciousness’ as untouched by the activities of the mind (Citta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There are a broad variety of the schools of yoga, practices, and goals[2] in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism,[3][4][5] and traditional forms and modern methods of yoga are practiced worldwide.[6]

There are broadly two kinds of theories on the origins of yoga. The linear model argues that yoga has Aryan origins, as reflected in the Vedic textual corpus, and influenced Buddhism; according to Crangle, this model is mainly supported by Hindu scholars. The synthesis model argues that yoga is a synthesis of indigenous, non-Aryan practices with Aryan elements; this model is favoured in western scholarship.[7]

Yoga is first mentioned in the Rigveda and also referenced in many Upanishads.[8][9][10] The first known formal appearance of the word “yoga”, with the same meaning as the modern term, is in the Katha Upanishad,[11][12] probably composed between the fifth and third century BCE.[13][14] Yoga continued to develop as a systematic study and practice during the 5th and 6th centuries BCE, in ancient India’s ascetic, and Śramaṇa movements.[15] The most comprehensive text on Yoga, Yoga Sutras of Patanjali date to the early centuries CE,[16][17][note 1] while Yoga philosophy came to be marked as one of the six orthodox philosophical schools of Hinduism in the second half of the first millennium.[18][web 1] Hatha yoga texts began to emerge between the 9th and 11th century with origins in tantra.[19][20]

The term “yoga” in the Western world often denotes a modern form of hatha yoga and a posture-based physical fitness, stress-relief and relaxation technique,[21] consisting largely of the asanas,[22] in contrast with traditional yoga, which focuses on meditation and release from worldly attachments.[21][23] It was introduced by gurus from India, following the success of Vivekananda’s adaptation of yoga without asanas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,[24] who introduced the Yoga Sutras to the west. The Yoga Sutras gained prominence in the 20th century following the success of hatha yoga.[

Etymology

A statue of Patañjali, the author of the core text Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, meditating in Padmasana.

The Sanskrit noun योग yoga is derived from the Sanskrit root yuj (युज्) “to attach, join, harness, yoke”.[26] The word yoga is cognate with English “yoke”.[27] According to Burley, the first use of the root of the word “yoga” is in hymn 5.81.1 of the Rig Veda, a dedication to the rising Sun-god in the morning (Savitri), where it has been interpreted as “yoke” or “yogically control”.[28][29][note 2]

According to Pāṇini (4th c. BCE), the term yoga can be derived from either of two roots, yujir yoga (to yoke) or yuj samādhau (“to concentrate”).[31] In the context of the Yoga Sutras, the root yuj samādhau (to concentrate) is considered by traditional commentators as the correct etymology.[32]

In accordance with Pāṇini, Vyasa who wrote the first commentary on the Yoga Sutras,[33] states that yoga means samādhi (concentration).[34] The term kriyāyoga has a technical meaning in the Yoga Sutras (2.1), designating the “practical” aspects of the philosophy, i.e. the “union with the supreme” through performance of duties in everyday life.[35]

Someone who practices yoga or follows the yoga philosophy with a high level of commitment is called a yogi (may be applied to a man or a woman) or yogini (a woman).[36]

Definition in classic Indian texts

The term Yoga has been defined in various ways in the many different Indian philosophical and religious traditions.

Goals

The ultimate goal of Yoga is stilling the mind and gaining insight, resting in detached awareness, released Moksha from Saṃsāra and Duḥkha. A process or discipline leading to oneness (Aikyam) with the Divine (Brahman) or with one’s Self (Atman).[41] The formulation of this goal varies with the philosophical or theological system with which it is conjugated. In the classical Astanga yoga system, the ultimate goal of yoga practice is to achieve the state of Samadhi and abide in that state as pure awareness.

According to Jacobsen, Yoga has five principal traditional meanings:[42]

- A disciplined method for attaining a goal.

- Techniques of controlling the body and the mind.

- A name of a school or system of philosophy (darśana).

- With prefixes such as “hatha-, mantra-, and laya-, traditions specialising in particular techniques of yoga.

- The goal of Yoga practice.[43]

According to David Gordon White, from the 5th century CE onward, the core principles of “yoga” were more or less in place, and variations of these principles developed in various forms over time:[44]

- A meditative means of discovering dysfunctional perception and cognition, as well as overcoming it to release any suffering, find inner peace, and salvation. Illustration of this principle is found in Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and Yogasutras, in a number of Buddhist Mahāyāna works, as well as Jain texts.[45]

- The raising and expansion of consciousness from oneself to being coextensive with everyone and everything. These are discussed in sources such as in Hinduism Vedic literature and its Epic Mahābhārata, Jainism Praśamaratiprakarana, and Buddhist Nikaya texts.[46]

- A path to omniscience and enlightened consciousness enabling one to comprehend the impermanent (illusive, delusive) and permanent (true, transcendent) reality. Examples of this are found in Hinduism Nyaya and Vaisesika school texts as well as Buddhism Mādhyamaka texts, but in different ways.[47]

- A technique for entering into other bodies, generating multiple bodies, and the attainment of other supernatural accomplishments. These are, states White, described in Tantric literature of Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Buddhist Sāmaññaphalasutta.[48] James Mallinson, however, disagrees and suggests that such fringe practices are far removed from the mainstream Yoga’s goal as meditation-driven means to liberation in Indian religions.[49]

White clarifies that the last principle relates to legendary goals of “yogi practice”, different from practical goals of “yoga practice,” as they are viewed in South Asian thought and practice since the beginning of the Common Era, in the various Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophical schools.[50]

History

There is no consensus on its chronology or origins, other than that yoga developed in ancient India. There are broadly two kinds of theories on the origins of yoga. The linear model argues that yoga has Aryan origins, as reflected in the Vedic textual corpus, and influenced Buddhism; this model is mainly supported by Hindu scholars.[7] The synthesis model argues that yoga is a synthesis of indigenous, non-Aryan practices with Aryan elements; this model is favoured in western scholarship.[7]

Pre-philosophical speculations of yoga began to emerge in the early Upanishads of the first half of the first millennium BCE. Expositions appear in Jain, Buddhist and proto-orthodox texts of c. 500 – c. 200 BCE. Between 200 BCE and 500 CE, “technical traditions of Indian philosophy (Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain) were taking form, collecting their teachings in sutra-collections, and a coherent philosophical system of “Patanjaliyogasastra” began to emerge.[51] The Middle Ages saw the development of many satellite traditions of yoga. Yoga came to the attention of an educated western public in the mid 19th century along with other topics of Indian philosophy.

Origins

Linear model

According to Crangle, Hindu researchers have favoured a linear theory, which attempts “to interpret the origin and early development of Indian contemplative practices as a sequential growth from an Aryan genesis”,[52][note 3] just like traditional Hinduism regards the Vedas to be the ultimate source of all spiritual knowledge.[54][note 4] According to Bryant, authors who tend to support Indigenous Aryanism also tend to support the linear model.[57]

Synthetic model

Heinrich Zimmer was a notable exponent of the synthesis-model,[54] arguing for non-Vedic Eastern states of India.[58] According to Zimmer, Yoga philosophy is reckoned to be part of the non-Vedic system, which also includes the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy, Jainism and Buddhism:[58] “[Jainism] does not derive from Brahman-Aryan sources, but reflects the cosmology and anthropology of a much older pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India [Bihar] – being rooted in the same subsoil of archaic metaphysical speculation as Yoga, Sankhya, and Buddhism, the other non-Vedic Indian systems.”[59][note 5] More recently, Gombrich[62] and Samuel[63] have argued that the śramaṇa movement originated in non-Vedic Greater Magadha.[62][63]

Thomas McEvilley favors a composite model where pre-Aryan yoga prototype existed in the pre-Vedic period and its refinement began in the Vedic period.[64] According to Flood, the argument that the Upanishads differ fundamentally from the Vedic ritual tradition, indicating non-Vedic influences, is compelling.[65] Yet, continuities may exist between those various traditions:

[T]his dichotomization is too simplistic, for continuities can undoubtedly be found between renunciation and vedic Brahmanism, while elements from non-Brahmanical, Sramana traditions also played an important part in the formation of the renunciate ideal.[66][note 6]

A common notion is that the ascetic traditions of the eastern Ganges plain drew from a common body of related practices and philosophies,[68][69][70] with proto-samkhya enumerations, and it’s notion of purusha and prakriti, as a common denominator.[71][70]

Indus Valley Civilisation

Some scholars of Yoga — Werner, McEvilley, Eliade — have argued the central figure of the (so-called) Pashupati seal to depict an asana posture.[11] Thus, the roots of yoga are traced back to IVC.[72]

However, this yogic identification is rejected by recent scholars — Geoffrey Samuel, Andrea R. Jain, Wendy Doniger et al. — as anachronistic unsubstantiated speculation; it is argued that the meaning of the figure will remain unknown until Harappan script is deciphered and the roots of Yoga can’t be tied with IVC.[72][73][note 7]

Earliest textual references (1000–500 BCE)

The Vedas, the only texts preserved from the early Vedic period and codified between c. 1200 and 900 BCE, contain references to yogic-like practices. These are mostly related to ascetics on the fringes of the Brahmanical order.[76][77]

The Nasadiya Sukta of the Rig Veda suggests the presence of an early Brahmanic contemplative tradition.[note 8] Techniques for controlling breath and vital energies are mentioned in the Atharvaveda and in the Brahmanas (the second layer of the Vedas, composed c. 1000–800 BCE).[76][80][81]

Flood states that “[t]he Samhitas [the mantras of the Vedas] contain some references […] to ascetics, namely the Munis or Keśins and the Vratyas.”[82] According to Werner (1977), the Rigveda does not describe yoga, and there is little evidence as to what the practices were.[77] The earliest description of “an outsider who does not belong to the Brahminic establishment” is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda, the youngest book or mandala of the Rigveda, which was codified around 1000 BCE.[77] According to Werner, there existed

…individuals who were active outside the trend of Vedic mythological creativity and the Brahminic religious orthodoxy and therefore little evidence of their existence, practices and achievements has survived. And such evidence as is available in the Vedas themselves is scanty and indirect. Nevertheless the indirect evidence is strong enough not to allow any doubt about the existence of spiritually highly advanced wanderers.[77]

According to Whicher (1998), scholarship frequently fails to see the connection between contemplative practices of the rishis and later yoga-practices.[83] Whicher states that “the proto-Yoga of the Vedic rishis is an early form of sacrificial mysticism and contains many elements characteristic of later Yoga that include: concentration, meditative observation, ascetic forms of practice (tapas), breath control practiced in conjunction with the recitation of sacred hymns during the ritual, the notion of self-sacrifice, impeccably accurate recitation of sacred words (prefiguring mantra-yoga), mystical experience, and the engagement with a reality far greater than our psychological identity or the ego.”[83]

According to Jacobsen (2018), “Bodily postures are closely related to the tradition of (tapas), ascetic practices in the Vedic tradition,” and ascetic practices used by Vedic priests “in their preparations for the performance of the sacrifice” may be precursors to Yoga.[76] Yet, “the ecstatic practice of enigmatic longhaired muni in Rgveda 10.136 and the ascetic performance of the vratya-s in the Atharvaveda outside of or on the fringe of the Brahmanical ritual order, have probably contributed more to the ascetic practices of yoga.”[76]

According to Bryant, it is in the Upanishads, composed in the late Vedic period, that practices recognizable as classical yoga first appear.[68] Alexander Wynne observes that formless meditation and elemental meditation might have originated in the Upanishadic tradition.[84] An early reference to meditation is made in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the earliest Hindu Upanishad.[82] The Chandogya Upanishad describes the five kinds of vital energies (prana). Concepts used later in many yoga traditions such as internal sound and veins (nadis) are also described in the Upanishad.[85] The practice of pranayama (consciously regulating breath) is mentioned in hymn 1.5.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (c. 900 BCE).[86] The practice of pratyahara (concentrating all of one’s senses on self) is mentioned in hymn 8.15 of Chandogya Upanishad (c. 800–700 BCE).[86][note 9] The Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana (th c. BCE) teaches mantra repetition and control of the breath.[88] Taittiriya Upanishad (6th c. BCE) defines yoga as the mastery of body and senses.[89] According to Flood, “[t]he actual term yoga first appears in the Katha Upanishad,[12] dated fifth [90] to first centuries BCE.[91]

Second urbanisation (500–200 BCE)

Systematic yoga concepts begin to emerge in the texts of c. 500–200 BCE such as the Early Buddhist texts, the middle Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata.[92][note 10]

Buddhism and śramaṇa movement

Prince Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) shaves his hair and becomes a sramana (a wandering ascetic or seeker). Borobudur, 8th century

The āsana in which the Jain Mahavira is said to have attained omniscience

According to Geoffrey Samuel, our “best evidence to date” suggests that yogic practices “developed in the same ascetic circles as the early śramaṇa movements (Buddhists, Jainas and Ajivikas), probably in around the sixth and fifth centuries BCE.” This occurred during what is called the ‘Second Urbanisation’ period.[15] According to Mallinson and Singleton, these traditions were the first to use psychophysical techniques, mainly known as dhyana and tapas. but later described as yoga, to strive for the goal of liberation (moksha, nirvana) from samsara (the round of rebirth).[95]

Werner states, “The Buddha was the founder of his [Yoga] system, even though, admittedly, he made use of some of the experiences he had previously gained under various Yoga teachers of his time.”[96] He notes:[97]

But it is only with Buddhism itself as expounded in the Pali Canon that we can speak about a systematic and comprehensive or even integral school of Yoga practice, which is thus the first and oldest to have been preserved for us in its entirety.[97]

The early Buddhist texts describe yogic and meditative practices, some of which the Buddha borrowed from the śramaṇa tradition.[98][99] The Pali canon contains three passages in which the Buddha describes pressing the tongue against the palate for the purposes of controlling hunger or the mind, depending on the passage.[100] However, there is no mention of the tongue being inserted into the nasopharynx as in true khecarī mudrā. The Buddha used a posture where pressure is put on the perineum with the heel, similar to even modern postures used to stimulate Kundalini.[101] Some of the major suttas that discuss yogic practice include the Satipatthana sutta (Four foundations of mindfulness sutta) and the Anapanasati sutta (Mindfulness of breathing sutta).

The chronology of completion of these yoga-related Early Buddhist Texts, however, is unclear, just like ancient Hindu texts.[102][103] Early known Buddhist sources like the Majjhima Nikāya mention meditation, while the Anguttara Nikāya describes Jhāyins (meditators) that resemble early Hindu descriptions of Muni, Kesins and meditating ascetics,[104] but these meditation-practices are not called yoga in these texts.[105] The earliest known specific discussion of yoga in the Buddhist literature, as understood in modern context are from the later Buddhist Yogācāra and Theravada schools.[105]

A yoga system that predated the Buddhist school is Jain yoga. But since Jain sources postdate Buddhist ones, it is difficult to distinguish between the nature of the early Jain school and elements derived from other schools.[106] Most of the other contemporary yoga systems alluded in the Upanishads and some Buddhist texts are lost to time.[107][108][note 11]

Upanishads

The Upanishads, composed in the late Vedic period, contain the first references to practices recognizable as classical yoga.[68] The first known appearance of the word “yoga”, with the same meaning as the modern term, is in the Katha Upanishad,[11][12] probably composed between the fifth and third century BCE,[13][14] where it is defined as the steady control of the senses, which along with cessation of mental activity, leading to a supreme state.[82][note 12] Katha Upanishad integrates the monism of early Upanishads with concepts of samkhya and yoga. It defines various levels of existence according to their proximity to the innermost being Ātman. Yoga is therefore seen as a process of interiorization or ascent of consciousness.[111][112] It is the earliest literary work that highlights the fundamentals of yoga. White states:

The earliest extant systematic account of yoga and a bridge from the earlier Vedic uses of the term is found in the Hindu Katha Upanisad (Ku), a scripture dating from about the third century BCE[…] [I]t describes the hierarchy of mind-body constituents—the senses, mind, intellect, etc.—that comprise the foundational categories of Sāmkhya philosophy, whose metaphysical system grounds the yoga of the Yogasutras, Bhagavad Gita, and other texts and schools (Ku3.10–11; 6.7–8).[113]

The hymns in Book 2 of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, another late first millennium BCE text, states a procedure in which the body is held in upright posture, the breath is restrained and mind is meditatively focussed, preferably inside a cave or a place that is simple, plain, of silence or gently flowing water, with no noises nor harsh winds.[114][115][112]

The Maitrayaniya Upanishad, likely composed in a later century than Katha and Shvetashvatara Upanishads but before Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, mentions sixfold yoga method – breath control (pranayama), introspective withdrawal of senses (pratyahara), meditation (dhyana), mind concentration (dharana), philosophical inquiry/creative reasoning (tarka), and absorption/intense spiritual union (samadhi).[11][112][116]

In addition to the Yoga discussion in above Principal Upanishads, twenty Yoga Upanishads as well as related texts such as Yoga Vasistha, composed in 1st and 2nd millennium CE, discuss Yoga methods.[9][10]

Macedonian historical texts

Alexander the Great reached India in the 4th century BCE. Along with his army, he took Greek academics with him who later wrote memoirs about geography, people and customs they saw. One of Alexander’s companion was Onesicritus, quoted in Book 15, Sections 63–65 by Strabo, who describes yogins of India.[117] Onesicritus claims those Indian yogins (Mandanis ) practiced aloofness and “different postures – standing or sitting or lying naked – and motionless”.[118]

Onesicritus also mentions his colleague Calanus trying to meet them, who is initially denied audience, but later invited because he was sent by a “king curious of wisdom and philosophy”.[118] Onesicritus and Calanus learn that the yogins consider the best doctrine of life as “rid the spirit of not only pain, but also pleasure”, that “man trains the body for toil in order that his opinions may be strengthened”, that “there is no shame in life on frugal fare”, and that “the best place to inhabit is one with scantiest equipment or outfit”.[117][118] These principles are significant to the history of spiritual side of yoga.[117] These may reflect the ancient roots of “undisturbed calmness” and “mindfulness through balance” in later works of Hindu Patanjali and Buddhist Buddhaghosa respectively, states Charles Rockwell Lanman;[117] as well as the principle of Aparigraha (non-possessiveness, non-craving, simple living) and asceticism discussed in later Hinduism and Jainism.[citation needed]

Mahabharata and Bhagavad Gita

Description of an early form of yoga called nirodhayoga (yoga of cessation) is contained in the Mokshadharma section of the 12th chapter (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata (third century BCE).[119] Nirodhayoga emphasizes progressive withdrawal from the contents of empirical consciousness such as thoughts, sensations etc. until purusha (Self) is realized. Terms like vichara (subtle reflection), viveka (discrimination) and others which are similar to Patanjali’s terminology are mentioned, but not described.[120] There is no uniform goal of yoga mentioned in the Mahabharata. Separation of self from matter, perceiving Brahman everywhere, entering into Brahman etc. are all described as goals of yoga. Samkhya and yoga are conflated together and some verses describe them as being identical.[121] Mokshadharma also describes an early practice of elemental meditation.[122] Mahabharata defines the purpose of yoga as the experience of uniting the individual ātman with the universal Brahman that pervades all things.[121]

Krishna narrating the Gita to Arjuna

The Bhagavad Gita (‘Song of the Lord’) is part of the Mahabharata and also contains extensive teachings on Yoga. According to Mallinson and Singleton, the Gita “seeks to appropriate yoga from the renunciate milieu in which it originated, teaching that it is compatible with worldly activity carried out according to one’s caste and life stage; it is only the fruits of one’s actions that are to be renounced.”[119] In addition to an entire chapter (ch. 6) dedicated to traditional yoga practice, including meditation,[123] it introduces three prominent types of yoga:[124]

- Karma yoga: The yoga of action.[125]

- Bhakti yoga: The yoga of devotion.[125]

- Jnana yoga: The yoga of knowledge.[126][127]

The Gita consists of 18 chapters and 700 shlokas (verses),[128] with each chapter named as a different yoga, thus delineating eighteen different yogas.[128][129][130] Some scholars divide the Gita into three sections, with the first six chapters with 280 shlokas dealing with Karma yoga, the middle six containing 209 shlokas with Bhakti yoga, and the last six chapters with 211 shlokas as Jnana yoga; however, this is rough because elements of karma, bhakti and jnana are found in all chapters.[128]

Philosophical sutras

Yoga is discussed in the ancient foundational Sutras of Hindu philosophy. The Vaiśeṣika Sūtra of the Vaisheshika school of Hinduism, dated to have been composed sometime between 6th and 2nd century BCE discusses Yoga.[note 13] According to Johannes Bronkhorst, an Indologist known for his studies on early Buddhism and Hinduism and a professor at the University of Lausanne, Vaiśeṣika Sūtra describes Yoga as “a state where the mind resides only in the Self and therefore not in the senses”.[131] This is equivalent to pratyahara or withdrawal of the senses, and the ancient Sutra asserts that this leads to an absence of sukha (happiness) and dukkha (suffering), then describes additional yogic meditation steps in the journey towards the state of spiritual liberation.[131]

Similarly, Brahma sutras – the foundational text of the Vedanta school of Hinduism, discusses yoga in its sutra 2.1.3, 2.1.223 and others.[132] Brahma sutras are estimated to have been complete in the surviving form sometime between 450 BCE to 200 CE,[133][134] and its sutras assert that yoga is a means to gain “subtlety of body” and other powers.[132] The Nyaya sutras – the foundational text of the Nyaya school, variously estimated to have been composed between the 6th-century BCE and 2nd-century CE,[135][136] discusses yoga in sutras 4.2.38–50. This ancient text of the Nyaya school includes a discussion of yogic ethics, dhyana (meditation), samadhi, and among other things remarks that debate and philosophy is a form of yoga.[137][138][139]

Classical era (200 BCE – 500 CE)

During the period between the Mauryan and the Gupta eras (c. 200 BCE–500 CE) the Indic traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism were taking form and coherent systems of yoga began to emerge.[51] This period witnessed many new texts from these traditions discussing and systematically compiling yoga methods and practices. Some key works of this era include the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali, the Yoga-Yājñavalkya, the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra and the Visuddhimagga.

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Traditional Hindu depiction of Patanjali as an avatar of the divine serpent Shesha

One of the best known early expressions of Brahmanical Yoga thought is the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (early centuries CE[16][17][note 1]), the original name of which may have been the Pātañjalayogaśāstra-sāṃkhya-pravacana (c. sometime between 325 – 425) which some scholars now believe included both the sutras and a commentary.[140] As the name suggests, the metaphysical basis for this text is the Indian philosophy termed Sāṃkhya. This atheistic school is mentioned in Kauṭilya’s Arthashastra as one of the three categories of anviksikis (philosophies) along with Yoga and Cārvāka.[141][142] The two schools have some differences as well. Yoga accepted the conception of “personal god”, while Samkhya developed as a rationalist, non-theistic/atheistic system of Hindu philosophy.[143][144][145] Sometimes Patanjali’s system is referred to as Seshvara Samkhya in contradistinction to Kapila’s Nirivara Samkhya.[146] The parallels between Yoga and Samkhya were so close that Max Müller says that “the two philosophies were in popular parlance distinguished from each other as Samkhya with and Samkhya without a Lord.”[147]

Karel Werner argued that the process of systematization of yoga which began in the middle and early Yoga Upanishads culminated with the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[note 14]

The Yoga Sutras are also influenced by the Sramana traditions of Buddhism and Jainism, and may represent a further Brahmanical attempt to adopt yoga from the Sramana traditions.[140] As noted by Larson, there are numerous parallels in the concepts in ancient Samkhya, Yoga and Abhidharma Buddhist schools of thought, particularly from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century AD.[150] Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras is a synthesis of these three traditions. From Samkhya, the Yoga Sutras adopt the “reflective discernment” (adhyavasaya) of prakrti and purusa (dualism), its metaphysical rationalism, as well its three epistemic methods of gaining reliable knowledge.[150] From Abhidharma Buddhism’s idea of nirodhasamadhi, suggests Larson, Yoga Sutras adopt the pursuit of altered state of awareness, but unlike Buddhism’s concept of no self nor soul, Yoga is physicalist and realist like Samkhya in believing that each individual has a Self (Atma).[150] The third concept Yoga Sutras synthesize into its philosophy is the ancient ascetic traditions of meditation and introspection, as well as the yoga ideas from middle Upanishads such as Katha, Shvetashvatara and Maitri.[150]

Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are widely regarded as the first compilation of the formal yoga philosophy.[note 15] The verses of the Yoga Sutras are terse. Many later Indian scholars studied them and published their commentaries, such as the Vyasa Bhashya (c. 350–450 CE).[151] Patanjali defines the word “yoga” in his second sutra:

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः

(yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ)

– Yoga Sutras 1.2

This terse definition hinges on the meaning of three Sanskrit terms. I. K. Taimni translates it as “Yoga is the inhibition (nirodhaḥ) of the modifications (vṛtti) of the mind (citta)”.[152]Swami Vivekananda translates the sutra as “Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis).”[153] Edwin Bryant explains that, to Patanjali, “Yoga essentially consists of meditative practices culminating in attaining a state of consciousness free from all modes of active or discursive thought, and of eventually attaining a state where consciousness is unaware of any object external to itself, that is, is only aware of its own nature as consciousness unmixed with any other object.”[154][155][156]

If the meaning of yoga is understood as the practice of nirodha (mental control), then its goal is “the unqualified state of niruddha (the perfection of that process)”,[157] according to Baba Hari Dass. In that context, “yoga (union) implies duality (as in joining of two things or principles); the result of yoga is the nondual state”, and “as the union of the lower self and higher Self. The nondual state is characterized by the absence of individuality; it can be described as eternal peace, pure love, Self-realization, or liberation.”[157]

Patanjali’s writing defined an Ashtanga or “Eight-Limbed” Yoga in Yoga Sutras 2.29. They are:

- Yama (The five “abstentions”): Ahimsa (Non-violence, non-harming other living beings),[158] Satya (truthfulness, non-falsehood),[159] Asteya (non-stealing),[160] Brahmacharya (celibacy, fidelity to one’s partner),[160] and Aparigraha (non-avarice, non-possessiveness).[159]

- Niyama (The five “observances”): Śauca (purity, clearness of mind, speech and body),[161] Santosha (contentment, acceptance of others and of one’s circumstances),[162] Tapas (persistent meditation, perseverance, austerity),[163] Svādhyāya (study of self, self-reflection, study of Vedas),[164] and Ishvara-Pranidhana (contemplation of God/Supreme Being/True Self).[162]

- Asana: Literally means “seat”, and in Patanjali’s Sutras refers to the seated position used for meditation.

- Pranayama (“Breath exercises”): Prāna, breath, “āyāma”, to “stretch, extend, restrain, stop”.

- Pratyahara (“Abstraction”): Withdrawal of the sense organs from external objects.

- Dharana (“Concentration”): Fixing the attention on a single object.

- Dhyana (“Meditation”): Intense contemplation of the nature of the object of meditation.

- Samadhi (“Liberation”): merging consciousness with the object of meditation.

In later Hindu scholasticism (12th century onwards), yoga became the name of one of the six orthodox philosophical schools (darsanas), which refers to traditions that accept the testimony of Vedas.[note 16][note 17][165]

Yoga and Vedanta

Yoga and Vedanta are the two largest surviving schools of Hindu traditions. They share many thematic principles, concepts, and beliefs in Self (Atman), but diverge in degree, style, and some of their methods. Epistemologically, Yoga school accepts three means to reliable knowledge, while Advaita Vedanta accepts six ways.[166] Yoga disputes the monism of Advaita Vedanta.[167] Yoga school believes that in the state of moksha, each individual discovers the blissful, liberating sense of himself or herself as an independent identity; Advaita Vedanta, in contrast, believes that in the state of moksha, each individual discovers the blissful, liberating sense of himself or herself as part of Oneness with everything, everyone and the Universal Self. They both hold that the free conscience is aloof yet transcendent, liberated and self-aware. Further, Advaita Vedanta school enjoins the use of Patanjali’s yoga practices and the reading of Upanishads for those seeking the supreme good, ultimate freedom and jivanmukti.[167]

संयोगो योग इत्युक्तो जीवात्मपरमात्मनोः॥

saṁyogo yoga ityukto jīvātma-paramātmanoḥ॥

Yoga is union of the individual self (jivātma) with the supreme self (paramātma).

—Yoga Yajnavalkya[168]

The Yoga Yajnavalkya is a classical treatise on yoga attributed to the Vedic sage Yajnavalkya. It takes the form of a dialogue between Yajnavalkya and Gargi, a renowned philosopher.[169] The text contains 12 chapters and its origin has been traced to the period between the second century BCE and fourth century CE.[170] Many yoga texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Yoga Kundalini and the Yoga Tattva Upanishads have borrowed verses from or make frequent references to the Yoga Yajnavalkya.[171] The Yoga Yajnavalkya discusses eight yoga Asanas – Swastika, Gomukha, Padma, Vira, Simha, Bhadra, Mukta and Mayura,[172] numerous breathing exercises for body cleansing,[173] and meditation.[174]

Buddhist Abhidharma and Yogacara

Asanga, a 4th-century CE scholar and a co-founder of the Yogacara (“Yoga practice”) school of Mahayana Buddhism.[175]

The Buddhist tradition of Abhidharma developed various treatises which further expanded teachings on Buddhist phenomenological theory and yogic techniques. These had a profound influence on Buddhist traditions such as the Mahayana and the Theravada.

During the Gupta period (4th to 5th centuries), a movement of northern Mahāyāna Buddhism termed Yogācāra began to be systematized with the writings of the Buddhist scholars Asanga and Vasubandhu. Yogācāra Buddhism received the name as it provided a “yoga,” a systematic framework for engaging in the practices that lead through the path of the bodhisattva towards awakening and full Buddhahood.[176] Its teachings can be found in the comprehensive and encyclopedic work, the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (Treatise on the Foundation for Yoga Practitioners), which was also translated into Tibetan and Chinese and thus exerted a profound influence on the East Asian Buddhist and Tibetan Buddhist traditions.[177] According to Mallinson and Singleton, the study of Yogācāra Buddhism is essential for the understanding of yoga’s early history, and its teachings influenced the text of the Pātañjalayogaśāstra.[178]

Like the northern tradition, the south India and Sri Lankan based Theravada school also developed manuals for yogic and meditative training, mainly the Vimuttimagga and the Visuddhimagga.

Jainism

According to Tattvarthasutra, 2nd century CE Jain text, yoga is the sum of all the activities of mind, speech and body.[5] Umasvati calls yoga the cause of “asrava” or karmic influx[179] as well as one of the essentials—samyak caritra—in the path to liberation.[179] In his Niyamasara, Acarya Kundakunda, describes yoga bhakti—devotion to the path to liberation—as the highest form of devotion.[180] Acarya Haribhadra and Acarya Hemacandra mention the five major vows of ascetics and 12 minor vows of laity under yoga. This has led certain Indologists like Prof. Robert J. Zydenbos to call Jainism, essentially, a system of yogic thinking that grew into a full-fledged religion.[181] The five yamas or the constraints of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali bear a resemblance to the five major vows of Jainism, indicating a history of strong cross-fertilization between these traditions.[181][note 18]

Mainstream Hinduism’s influence on Jain yoga can be see in Haribhadra’s Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya which outlines an eightfold yoga influenced by Patanjali’s eightfold yoga.[183]

Middle Ages (500–1500 CE)

Middle Ages saw the development of many satellite traditions of yoga. Hatha yoga emerged in this period.[184]

Bhakti movement

The Bhakti movement was a development in medieval Hinduism which advocated the concept of a personal God (or “Supreme Personality of Godhead”). The movement was initiated by the Alvars of South India in the 6th to 9th centuries, and it started gaining influence throughout India by the 12th to 15th centuries.[185] Shaiva and Vaishnava bhakti traditions integrated aspects of Yoga Sutras, such as the practical meditative exercises, with devotion.[186] Bhagavata Purana elucidates the practice of a form of yoga called viraha (separation) bhakti. Viraha bhakti emphasizes one pointed concentration on Krishna.[187]

Hindu Tantra

Tantra is a range of esoteric traditions that began to arise in India no later than the 5th century CE.[188][note 19] George Samuel states, “Tantra” is a contested term, but may be considered as a school whose practices appeared in mostly complete form in Buddhist and Hindu texts by about 10th century CE.[190] Tantric yoga developed complex visualizations which included meditation on the body as a microcosm of the cosmos. They included also the use of mantras, pranayama, and the manipulation of the subtle body, including its nadis and cakras. These teachings on cakras and Kundalini would become central to later forms of Indian Yoga.[191]

Over its history, some ideas of Tantra school influenced the Hindu, Bon, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. Elements of Tantric yoga rituals were adopted by and influenced state functions in medieval Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms in East and Southeast Asia.[192] By the turn of the first millennium, hatha yoga emerged from tantra.[19][193]

Vajrayana and Tibetan Buddhism

Vajrayana is also known as Tantric Buddhism and Tantrayāna. Its texts were compiled starting with 7th century and Tibetan translations were completed in the 8th century CE. These tantra yoga texts were the main source of Buddhist knowledge that was imported into Tibet.[194] They were later translated into Chinese and other Asian languages, helping spread ideas of Tantric Buddhism. The Buddhist text Hevajra Tantra and Caryāgiti introduced hierarchies of chakras.[195] Yoga is a significant practice in Tantric Buddhism.[196][197][198]

The tantra yoga practices include asanas and breathing exercises. The Nyingma tradition practices Yantra yoga (Tib. “Trul khor”), a discipline that includes breath work (or pranayama), meditative contemplation and other exercises.[199] In the Nyingma tradition, the path of meditation practice is divided into further stages,[200] such as Kriya yoga, Upa yoga, Yoga yana, Mahā yoga, Anu yoga and Ati yoga.[201] The Sarma traditions also include Kriya, Upa (called “Charya”), and Yoga, with the Anuttara yoga class substituting for Mahayoga and Atiyoga.[202]

Zen Buddhism

Zen, the name of which derives from the Sanskrit “dhyāna” via the Chinese “ch’an”[note 20] is a form of Mahayana Buddhism. Yoga practices integrally exist within the Zen Buddhist school.[204]

Hatha Yoga

A sculpture of Gorakshanath, a celebrated 11th century yogi of Nath tradition and a major proponent of Hatha yoga[205]

The earliest references to hatha yoga are in Buddhist works dating from the eighth century.[206] The earliest definition of hatha yoga is found in the 11th century Buddhist text Vimalaprabha, which defines it in relation to the center channel, bindu etc.[207] Hatha yoga synthesizes elements of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras with posture and breathing exercises.[208] It marks the development of asanas (plural) into the full body ‘postures’ now in popular usage[193] and, along with its many modern variations, is the style that many people associate with the word yoga today.[209]

Sikhism

Various yogic groups had become prominent in Punjab in the 15th and 16th century, when Sikhism was in its nascent stage. Compositions of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, describe many dialogues he had with Jogis, a Hindu community which practiced yoga. Guru Nanak rejected the austerities, rites and rituals connected with Hatha Yoga. He propounded the path of Sahaja yoga or Nama yoga (meditation on the name) instead.[210] The Guru Granth Sahib states:

Listen “O Yogi, Nanak tells nothing but the truth. You must discipline your mind. The devotee must meditate on the Word Divine. It is His grace which brings about the union. He understands, he also sees. Good deeds help one merge into Divination.”[211]

Modern revival

Swami Vivekananda in London in 1896

Introduction in the west

Yoga came to the attention of an educated western public in the mid-19th century along with other topics of Indian philosophy. In the context of this budding interest, N. C. Paul published his Treatise on Yoga Philosophy in 1851.[212]

The first Hindu teacher to actively advocate and disseminate aspects of yoga, not including asanas, to a western audience, Swami Vivekananda, toured Europe and the United States in the 1890s.[213] The reception which Swami Vivekananda received built on the active interest of intellectuals, in particular the New England Transcendentalists, among them Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), who drew on German Romanticism and philosophers and scholars like G. W. F. Hegel (1770–1831), the brothers August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767–1845) and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829), Max Mueller (1823–1900), Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), and others who had (to varying degrees) interests in things Indian.[214][215]

Theosophists including Madame Blavatsky also had a large influence on the Western public’s view of Yoga.[216] Esoteric views current at the end of the 19th century provided a further basis for the reception of Vedanta and of Yoga with its theory and practice of correspondence between the spiritual and the physical.[217] The reception of Yoga and of Vedanta thus entwined with each other and with the (mostly Neoplatonism-based) currents of religious and philosophical reform and transformation throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Mircea Eliade brought a new element into the reception of Yoga with the strong emphasis on Tantric Yoga in his seminal book: Yoga: Immortality and Freedom.[218] With the introduction of the Tantra traditions and philosophy of Yoga, the conception of the “transcendent” to be attained by Yogic practice shifted from experiencing the “transcendent” (“Atman-Brahman” in Advaitic theory) in the mind to the body itself.[219]

Yoga as a physical practice

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting largely of asanas, often connected by flowing sequences called vinyasas, sometimes accompanied by the breathing exercises of pranayama, and usually ending with a period of relaxation or meditation. It is often known simply as yoga,[220] despite the existence of multiple older traditions of yoga within Hinduism where asanas played little or no part, some dating back to the Yoga Sutras, and despite the fact that in no tradition was the practice of asanas central.[221]

Yoga as exercise was created in what has been called the Modern Yoga Renaissance[222] by the blending of Western styles of gymnastics with postures from Haṭha yoga in India in the 20th century, pioneered by Shri Yogendra and Swami Kuvalayananda.[223] Before 1900 there were few standing poses in Haṭha yoga. The flowing sequences of salute to the Sun, Surya Namaskar, were pioneered by the Rajah of Aundh, Bhawanrao Shrinivasrao Pant Pratinidhi, in the 1920s.[224] Many standing poses used in gymnastics were incorporated into yoga by Krishnamacharya in Mysore from the 1930s to the 1950s.[225] Several of his students went on to found influential schools of yoga: Pattabhi Jois created Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga,[226] which in turn led to Power Yoga;[227] B. K. S. Iyengar created Iyengar Yoga, and systematised the canon of asanas in his 1966 book Light on Yoga;[228] Indra Devi taught yoga to many film stars in Hollywood; and Krishnamacharya’s son T. K. V. Desikachar founded the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandalam in Chennai.[229][230][231] Other major schools founded in the 20th century include Bikram Choudhury’s Bikram Yoga and Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh’s Sivananda Vedanta Schools of Yoga. Modern yoga spread across America and Europe, and then the rest of the world.[232][233]

The number of asanas used in yoga as exercise has increased rapidly from a nominal 84 in 1830, as illustrated in Joga Pradipika, to some 200 in Light on Yoga and over 900 performed by Dharma Mittra by 1984. At the same time, the goals of Haṭha yoga, namely spiritual liberation (moksha) through the raising of kundalini energy, were largely replaced by the goals of fitness and relaxation, while many of Haṭha yoga’s components like the shatkarmas (purifications), mudras (seals or gestures including the bandhas, locks to restrain the prana or vital principle), and pranayama were much reduced or removed entirely.[234] The term “hatha yoga” is also in use with a different meaning, a gentle unbranded yoga practice, independent of the major schools, sometimes mainly for women.[235]

International Day of Yoga in New Delhi, 2016

Yoga has developed into a worldwide multi-billion dollar business, involving classes, certification of teachers, clothing, books, videos, equipment, and holidays.[236] The ancient cross-legged sitting asanas like lotus pose (Padmasana) and Siddhasana are widely recognised symbols of yoga.[237]

The United Nations General Assembly established 21 June as “International Day of Yoga”,[238][239][240] celebrated annually in India and around the world from 2015.[241][242] On 1 December 2016, yoga was listed by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage.[243]

The impact of postural yoga on physical and mental health has been a topic of systematic studies, with evidence that regular yoga practice yields benefits for low back pain and stress.[244][245] In 2017, a Cochrane review found low‐ to moderate‐certainty evidence that yoga improved back function compared to non-exercise.[246]

Traditions

Yoga is practised with a variety of methods by all Indian religions. In Hinduism, practices include Jnana Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Karma Yoga, Laya Yoga and Hatha Yoga.

Jain yoga

Jain yoga has been a central practice in Jainism. Jain spirituality is based on a strict code of nonviolence or ahimsa (which includes vegetarianism), almsgiving (dāna), right faith in the three jewels, the practice of austerities (tapas) such as fasting, and yogic practices.[247][248] Jain yoga aims at the liberation and purification of the Self (atma) or individual Self (jiva) from the forces of karma, which keep all Selfs bound to the cycle of transmigration. Like Yoga and Sankhya, Jainism believes in a multiplicity of individual Selfs which bound by their individual karma.[249] Only through the reduction of karmic influxes and the exhaustion of one’s collected karma can a Self become purified and released, at which point one becomes an omniscient being who has reaches “absolute knowledge” (kevala jnana).[250]

The early practice of Jain yoga seems to have been divided into several types, including meditation (dhyāna), abandonment of the body (kāyotsarga), contemplation (anuprekṣā), and reflection (bhāvanā).[251] Some of the earliest sources for Jain yoga are the Uttarādhyayana-sūtra, the Āvaśyaka-sūtra, the Sthananga Sutra (c. 2nd century BCE). Later works include Kundakunda’s Vārassa-aṇuvekkhā (“Twelve Contemplations”, c. 1st century BCE to 1st century CE), Haribhadra’s Yogadṛṣṭisamuccya (8th century) and the Yogaśāstra of Hemachandra (12th century). Later forms of Jain yoga adopted Hindu influences, such as ideas from Patanjali’s yoga and later Tantric yoga (in the works of Haribhadra and Hemachandra respectively). The Jains also developed a progressive path to liberation through yogic praxis, outlining several levels of virtue called gunasthanas.

In the modern era, new forms of Jain meditation have also been developed. One of the most influential ones is the prekṣā system of Ācārya Mahāprajña which is eclectic and includes the use of mantra, breath control, mudras, bandhas, and so on.

Buddhist yoga

Sakyamuni Buddha in seated meditation with the dhyāna mudrā (meditation mudra), Gal Vihara, Sri Lanka.

Buddhist yoga encompasses an extensive variety of methods that aim to develop key virtues or qualities known as the 37 aids to awakening. The ultimate goal of Buddhist yoga is bodhi (awakening) or nirvana (cessation), which is traditionally seen as the permanent end of suffering (dukkha) and rebirth.[note 21] Buddhist texts use numerous terms for spiritual praxis besides yoga, such as bhāvanā (“development”)[note 22] and jhāna/dhyāna.[note 23]

In early Buddhism, various yogic practices were taught including:

- the four dhyānas (four meditations or mental absorptions),

- the four satipatthanas (foundations or establishments of mindfulness),

- anapanasati (mindfulness of breath),

- the four immaterial dwellings (supranormal states of mind),

- the brahmavihārās (divine abodes).

- Anussati (contemplations, recollections)

These meditations were seen as being supported by the other elements of the eightfold path, such as the practice of ethics, right exertion, sense restraint and right view.[252] Two mental qualities are said to be indispensable for yogic practice in Buddhism, samatha (calm, stability) and vipassanā (insight, clear seeing).[253] Samatha is the quality of a stable, relaxed and calm mind. It is also associated with samadhi (mental unification, focus) and dhyana (a state of meditative absorption). Vipassanā meanwhile, is a kind of insight or penetrative understanding into the true nature of phenomena. It is also defined as “seeing things as they truly are” (yathābhūtaṃ darśanam). The true nature of things is defined and explained in different ways, but an important and unique feature of classical Buddhism is its understanding of all phenomena (dhammas) as being empty of a self (atman) or inherent essence, a doctrine termed Anatta (“not-self”) and Śūnyatā (emptiness).[254][255] This is in sharp contrast with most other Indian traditions, whose goals are founded either on the idea of an individual Self (atman, jiva, purusha) or a universal monistic consciousness ( Brahman). Vipassanā also requires an understanding of suffering or dukkha (and thus the four noble truths), impermanence (anicca) and interdependent origination.

Later developments in the various Buddhist traditions led to new innovations in yogic practices. The Theravada school, while remaining relatively conservative, still developed new ideas on meditation and yogic phenomenology in their later works, the most influential of which is the Visuddhimagga. The Indic meditation teachings of Mahayana Buddhism can be seen in influential texts like the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (compiled c. 4th century). Mahayana meditation practices also developed and adopted new yogic methods, such as the use of mantra and dharani, pure land practices which aimed at rebirth in a pure land or buddhafield, and visualization methods. Chinese Buddhism developed its own methods, such as the Chan practice of Koan introspection and Hua Tou. Likewise, Tantric Buddhism (also Mantrayana, Vajrayana) developed and adopted tantric methods, which remain the basis of the Tibetan Buddhist yogic systems, including the deity yoga, guru yoga, the six yogas of Naropa, Kalacakra, Mahamudra and Dzogchen.[256]

Classical yoga

What is often referred to as Classical Yoga, Astanga (Yoga of eight limbs), or Raja Yoga is mainly the type of Yoga outlined in the highly influential Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[257] The origins of the Classical Yoga tradition are unclear, though early discussions of the term appear in the Upanishads.[150] The name “Rāja yoga” (yoga of kings) originally denoted the ultimate goal of yoga, samadhi,[258] but was popularised by Vivekananda as a common name for Ashtanga Yoga,[note 24] the eight limbs to be practised to attain samadhi, as described in the Yoga Sutras.[259][257] Yoga philosophy came to be regarded as a distinct orthodox philosophical schools (darsanas) of Hinduism (those which accept the Vedas as source of knowledge) in the second half of the first millennium CE.[18][web 1]

Classical yoga incorporates epistemology, metaphysics, ethical practices, systematic exercises and self-development techniques for body, mind and spirit.[154] Its epistemology (pramana) and metaphysics is similar to that of the Sāṅkhya school. The metaphysics of Classical Yoga, like Sāṅkhya, is mainly dualistic, positing that there are two distinct realities. These are prakriti (nature), which is the eternal and active unconscious source of the material world and is composed of three gunas, and the puruṣas (persons), the plural consciousnesses which are the intelligent principles of the world, and are multiple, inactive and eternal witnesses. Each person has an individual puruṣa, which is their true self, the witness and the enjoyer, and that which is liberated. This metaphysical system holds that puruṣas undergo cycles of reincarnation through its interaction and identification with prakirti. Liberation, the goal of this system, results from the isolation (kaivalya) of puruṣa from prakirti, and is achieved through a meditation which detaches oneself from the different forms (tattvas) of prakirti.[260] This is done by stilling one’s thought waves (citta vritti) and resting in pure awareness of puruṣa.

Unlike the Sāṅkhya school of Hinduism, which pursues a non-theistic/atheistic rationalist approach,[143][261] the Yoga school of Hinduism accepts the concept of a “personal, yet essentially inactive, deity” or “personal god” (Ishvara).[262][263]

In Advaita Vedanta

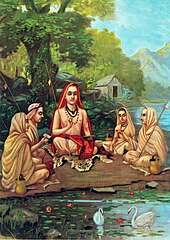

Adi Shankara with Disciples, by Raja Ravi Varma (1904). Studying Vedic scripture with a guru is central to the Jñāna yoga of Advaita Vedanta.

Vedanta is a varied tradition with numerous sub-schools and philosophical views. Vedanta focuses on the study of the Upanishads, and one of its early texts, the Brahma sutras. Regarding yoga or meditation, the Brahma sutras focuses on gaining spiritual knowledge of Brahman, the unchanging absolute reality or Self.[264]

One of the earliest and most influential sub-traditions of Vedanta, is Advaita Vedanta, which posits non-dualistic monism. This tradition emphasizes Jñāna yoga (yoga of knowledge), which is aimed at realizing the identity of one’s atman (Self, individual consciousness) with Brahman (the Absolute consciousness).[265][266] The most influential thinker of this school is Adi Shankara (8th century), who wrote various commentaries and original works which teach Jñāna yoga. In Advaita Vedanta, Jñāna is attained on the basis of scripture (sruti) and one’s guru and through a process of listening (sravana) to teachings, thinking and reflecting on them (manana) and finally meditating on these teachings (nididhyāsana) in order to realize their truth.[267] It is also important to develop qualities such as discrimination (viveka), renunciation (virāga), tranquility, temperance, dispassion, endurance, faith, attention and a longing for knowledge and freedom (‘mumukṣutva).’[268] Yoga in Advaita is ultimately a “meditative exercise of withdrawal from the particular and identification with the universal, leading to contemplation of oneself as the most universal, namely, Consciousness”.[269]

An influential text which teaches yoga from an Advaita perspective of nondualistic idealism is the Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha.[270] This work uses numerous short stories and anecdotes to illustrate its main ideas. It teaches seven stages or bhumis of yogic practice. It was a major reference for medieval Advaita Vedanta yoga scholars and before the 12th century, it was one of the most popular texts on Hindu yoga.[271]

Another text which teaches yoga with an Advaita point of view is the Yoga-Yājñavalkya.[272] This work contains extensive teachings on ten Yamas (ethical rules) and ten Niyamas (duties), and eight asanas. It also discusses a theory of nadis and prana (vital breath), and follows this with instructions on pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (sense withdrawal), meditation on mantras, meditative visualizations and Kundalini.

Tantric yoga

Samuel states that Tantrism is a contested concept.[190] Tantra yoga may be described, according to Samuel, as practices in 9th to 10th century Buddhist and Hindu (Saiva, Shakti) texts, which included yogic practices with elaborate deity visualizations using geometrical arrays and drawings (mandala), fierce male and particularly female deities, transgressive life stage related rituals, extensive use of chakras and mantras, and sexual techniques, all aimed to help one’s health, long life and liberation.[190][273]

Hatha yoga

Viparītakaraṇī, a posture used both as an asana and as a mudra[274]

Hatha yoga, also called hatha vidyā, is a kind of yoga focusing on physical and mental strength building exercises and postures described primarily in three texts of Hinduism:[275][276][277]

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Svātmārāma (15th century)

- Shiva Samhita, author unknown (1500[278] or late 17th century)

- Gheranda Samhita by Gheranda (late 17th century)

Many scholars would include the Goraksha Samhita by Gorakshanath of the 11th century in this list.[275] Gorakshanath is widely considered to have been responsible for popularizing hatha yoga as we know it today.[279][280][281] Other hatha yoga texts include the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati, the Hatha Ratnavali, the Joga Pradīpikā, and the Sritattvanidhi.

Vajrayana Buddhism, founded by the Indian Mahasiddhas,[282] has a series of asanas and pranayamas, such as tummo (Sanskrit caṇḍālī)[196] and trul khor which parallel hatha yoga.

Laya yoga and kundalini yoga

Laya and kundalini yoga are closely associated with Hatha yoga but are often presented as being independent approaches.[35]

According to Georg Feuerstein, laya yoga (yoga of dissolution or merging) “makes meditative absorption (laya) its focus. The laya-yogin seeks to transcend all memory traces and sensory experiences by dissolving the microcosm, the mind, in the transcendental Self-Consciousness.”[283] There are various forms and techniques of Laya yoga, including listening to the “inner sound” (nada), practicing various mudras like Khechari mudra and Shambhavi mudra as well as techniques meant to awaken a spiritual energy in the body (kundalini).[284]

The practice of awakening the coiled energy in the body is sometimes specifically called Kundalini yoga. It is based on Indian theories of the subtle body and uses various pranayamas (breath techniques) and mudras (bodily techniques) to awaken the energy known as kundalini (the coiled one) or shakti. In various Shaiva and Shakta traditions of yoga and tantra, yogic techniques or yuktis are used to unite kundalini-shakti, the divine conscious force or energy, with Shiva, universal consciousness.[285] A common way of teaching this method is to awaken the kundalini residing at the lowest chakra and to guide it through the central channel to unite with the absolute consciousness at the highest chakra (in the top of the head).[286]

Reception in other religions

Christianity

Some Christians integrate physical aspects of yoga, stripped from the spiritual roots of Hinduism, and other aspects of Eastern spirituality with prayer, meditation and Jesus-centric affirmations.[287][288] The practice also includes renaming poses in English (rather than using the original Sanskrit terms), and abandoning involved Hindu mantras as well as the philosophy of Yoga; Yoga is associated and reframed into Christianity.[288] This has drawn charges of cultural appropriation from various Hindu groups;[288][289] scholars remain skeptical.[290] Previously, the Roman Catholic Church, and some other Christian organizations have expressed concerns and disapproval with respect to some eastern and New Age practices that include yoga and meditation.[291][292][293]

In 1989 and 2003, the Vatican issued two documents: Aspects of Christian meditation and “A Christian reflection on the New Age,” that were mostly critical of eastern and New Age practices. The 2003 document was published as a 90-page handbook detailing the Vatican’s position.[294] The Vatican warned that concentration on the physical aspects of meditation “can degenerate into a cult of the body” and that equating bodily states with mysticism “could also lead to psychic disturbance and, at times, to moral deviations.” Such has been compared to the early days of Christianity, when the church opposed the gnostics’ belief that salvation came not through faith but through a mystical inner knowledge.[287] The letter also says, “one can see if and how [prayer] might be enriched by meditation methods developed in other religions and cultures”[295] but maintains the idea that “there must be some fit between the nature of [other approaches to] prayer and Christian beliefs about ultimate reality.”[287] Some[which?] fundamentalist Christian organizations consider yoga to be incompatible with their religious background, considering it a part of the New Age movement inconsistent with Christianity.[296]

Islam

In the early 11th century, the Persian scholar Al Biruni visited India, lived with Hindus for 16 years, and with their help translated several significant Sanskrit works into Arabic and Persian languages. One of these was Patanjali’s Yogasutras.[297][298] Al Biruni’s translation preserved many of the core themes of Patañjali ‘s Yoga philosophy, but certain sutras and analytical commentaries were restated making it more consistent with Islamic monotheistic theology.[297][299] Al Biruni’s version of Yoga Sutras reached Persia and Arabian peninsula by about 1050 AD. Later, in the 16th century, the hath yoga text Amritakunda was translated into Arabic and then Persian.[300] Yoga was, however, not accepted by mainstream Sunni and Shia Islam. Minority Islamic sects such as the mystic Sufi movement, particularly in South Asia, adopted Indian yoga practises, including postures and breath control.[301][302] Muhammad Ghawth, a Shattari Sufi and one of the translators of yoga text in the 16th century, drew controversy for his interest in yoga and was persecuted for his Sufi beliefs.[303]

Malaysia’s top Islamic body in 2008 passed a fatwa, prohibiting Muslims from practicing yoga, saying it had elements of Hinduism and that its practice was blasphemy, therefore haraam.[304] Some Muslims in Malaysia who had been practicing yoga for years, criticized the decision as “insulting.”[305] Sisters in Islam, a women’s rights group in Malaysia, also expressed disappointment and said yoga was just a form of exercise.[306] This fatwa is legally enforceable.[307] However, Malaysia’s prime minister clarified that yoga as physical exercise is permissible, but the chanting of religious mantras is prohibited.[308]

In 2009, the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), an Islamic body in Indonesia, passed a fatwa banning yoga on the grounds that it contains Hindu elements.[309] These fatwas have, in turn, been criticized by Darul Uloom Deoband, a Deobandi Islamic seminary in India.[310] Similar fatwas banning yoga, for its link to Hinduism, were issued by the Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa in Egypt in 2004, and by Islamic clerics in Singapore earlier.[311][312]

In Iran, as of May 2014, according to its Yoga Association, there were approximately 200 yoga centres in the country, a quarter of them in the capital Tehran, where groups can often be seen practising in parks. This has been met by opposition among conservatives.[313] In May 2009, Turkey’s head of the Directorate of Religious Affairs, Ali Bardakoğlu, discounted personal development techniques such as reiki and yoga as commercial ventures that could lead to extremism. His comments were made in the context of reiki and yoga possibly being a form of proselytization at the expense of Islam.[314] In 2017, Nouf Marwaai is the yoga instructor who bought yoga to Saudi Arabia for the first time and contributed to making yoga legal and get official recognition in Saudi Arabia, despite being allegedly threatened by her community who considers yoga to be “un-Islamic”.[315]

You have remarked very interesting details! ps nice internet site.