Ernesto Guevara was born in Argentina on June 14, 1928.

Ernesto Guevara was born in Argentina on June 14, 1928.

He became an Argentine-born Marxist revolutionary and Cuban guerrilla leader. “Che” is an Argentine expression for calling someone’s attention, and in some other parts of Latin America, a slang for someone from Argentina.

In 1951, Ernesto set off from his home town of Córdoba on a motorcycle tour of Central and South America along with his friend Alberto Granado. He went as far as Caracas, Venezuela, travelling by motorcycle, airplane, foot, boat and a raft, a journey recounted in his book The Motorcycle Diaries.

The poverty he observed during this trip led him to intensify his study of Marxist ideologies. Following his graduation from the University of Buenos Aires medical school in 1953, he travelled to Guatemala where a populist leader, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, had recently been elected president. Ernesto met several followers of Fidel Castro who were in exile there. When the CIA sponsored an overthrow of Arbenz’s rule, Ernesto volunteered to fight. Arbenz told his supporters to leave the country, and Ernesto briefly took refuge in the Argentine consulate. After moving to Mexico City, he renewed his friendship with Castro’s associates. Ernesto met Castro when the latter arrived in the Mexican capital after being amnestied from political prison in Cuba, and joined his 26th of July Movement dedicated to the overthrow of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista.

Castro, Che and 80 other insurgents departed Tuxpan, Mexico aboard the cabin cruiser “Granma” in November 1956 to invade Cuba and start the revolution. The boat had been owned by an American, so the name most likely meant Grandma, as a tribute to the previous owner’s grandmother. Shortly after disembarking in a swampy area near Niquero in Southeast Cuba, the expeditionaries were attacked by Batista’s forces. Only 12 rebels survived. Che, the group’s physician, laid down his knapsack containing medical supplies in order to pick up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, a moment which he later recalled as marking his transition from doctor to combatant. Within months he rose to the highest rank, Comandante (Major), in the revolutionary army. His march on Santa Clara in late 1958, where his column derailed an armored train filled with Batista’s troops and took over the city, was the final straw that forced Batista to flee the country.

His execution of informers, insubordinates, deserters and spies in the revolutionary army has led some to consider Guevara a ruthless leader. He personally executed Eutimio Guerra, a suspected Batista informant, with one shot from his .32 pistol. On another occasion he had planned on shooting a group of fellow guerillas who had gone on a hunger strike because of bad food, but Castro intervened and calmed Guevara down. Another guerrilla who dared to question Che was ordered into battle without a weapon.

Those persons executed by Guevara or on his orders were condemned for the usual crimes punishable by death at times of war or in its aftermath: desertion, treason or crimes such as rape, torture or murder although none of these persons punished by Guevara had the formality of a trial or general court marshal proceedings.

In contrast to this picture of Guevara as ruthless, when his column had captured enemy soldiers who had not committed crimes against the public such as rape and torture, he would simply take their ammunition and release them.

In 1959, Che Guevara was appointed commander of the La Cabana Fortress prison. During his term as commander of the fortress from 1959-1963, he oversaw the execution of what some estimate to be approximately 500 political prisoners and regime opponents. Many individuals imprisoned at La Cabana, such as poet and human rights activist Armando Valladares, allege that Guevara took particular and personal interest in the interrogation, torture, and execution of some prisoners.

Prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis, Guevara was part of a Cuban delegation to Moscow in early 1962 with Raúl Castro where he endorsed the planned placement of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Guevara believed that the placement of Soviet missiles would protect Cuba from any direct military action against it from the United States. Jon Lee Anderson reports that after the crisis Guevara told Sam Russell, a British correspondent for the socialist Daily Worker, that if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them off in a first strike.

Unlike other leaders, he gave up all the trappings of privilege and power in Cuba in order to return to the revolutionary battlefield and ultimately, to die. He persuaded Castro to back him in the first, covert Cuban involvement in Africa. Guevara desired to first work with the Simba (aka “Lumumbaist”) movement in the former Belgian Congo (later Zaire and currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo), with the goal of overthrowing the government and installing a Communist regime.

Che was only 35 at that time and had never any military training (his asthma prevented him from going to military service in Argentina, and he was proud of it). He had only his few experiences in the Cuban revolution and what he had read in books. As a consequence, every military operation planned by him failed. U.S. Army Special Forces advisors working with the Congolese army were able to monitor Che’s communications, arrange to ambush the rebels and the Cubans whenever they attempted to attack, and interdict Guevara’s supply lines. Guevara proved unable to supplant the native Simba leadership, and in fact was forced to place his troops under Simba command. Late that same year, ill, humiliated and with only a few survivors of the force he had brought into the country, Guevara left the Congo.

Following a lengthy recuperation in Cuba, traveling on a false passport Guevara entered Bolivia in November of 1966, again with the idea of organizing a revolt, toppling Bolivia’s pro-U.S. military government and installing a communist government there. A parcel of jungle land in Nancahazu was purchased by native communists and turned over to him for use as a training area. The evidence suggests that this training was more hazardous than combat to Guevara and the Cubans accompanying him. Little was accomplished in the way of building a guerrilla army. On learning of his presence in Bolivia, President Rene Barrientos is alleged to have expressed the desire to see Che’s head displayed on a pike in downtown La Paz. He ordered the Bolivian Army to hunt Guevara and his followers down.

Guevara’s hope of fomenting revolution in Bolivia appear to have been predicated upon a number of misconceptions. He had expected to deal only with an oppressive national government. However, there was an American presence in Bolivia. After the U.S. government learned of his location, CIA operatives were sent into Bolivia to aid the anti-insurrection effort. He had expected to deal with a poorly trained and equipped national army. Instead, the Bolivian Army was being trained by US Army Special Forces advisors, including a recently organized elite battalion of Rangers trained in jungle warfare. Che had expected assistance and cooperation from the local dissidents when he undertook his journey. Fidel had told him that the Communist Party in Bolivia would aid him in the insurrection. In the event, they did not.

Che and his associates found themselves hamstrung in Bolivia by the American aid and military trainers to the Bolivian government and a lack of assistance from his allies. In addition, the CIA also helped anti-Castro Cuban exiles to set up interrogation houses for those Bolivians thought to be assisting Che Guevara and/or his guerillas, which were often used for torture of these individuals.

The Bolivians were notified of the location of Guevara’s guerilla encampment by a deserter. On October 8th, 1967 the encampment was encircled and Che was captured while leading a patrol in the vicinity of La Higuera, Bolivia. His surrender was offered after being wounded in the legs and having his rifle destroyed by a bullet. According to soldiers present at the capture, during the skirmish as soldiers approached Guevara he shouted, “Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead.” Barrientos ordered his execution immediately upon being informed of Guevara’s capture. Guevara was summarily executed; he was taken to an old schoolhouse and bound by his hands to a board. Supposedly, Ernesto Guevara did have some last words before his death; he allegedly said to his executioner, “Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man,” after which he was shot in the heart.

A CIA agent and veteran of the US invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, Felix Rodriguez, heard of Guevara’s capture and relayed the information to the CIA. He has said on multiple occasions that he was the one that shot Guevara. (This is generally thought to be untrue.) After the execution, Rodriguez took Che’s Rolex watch, often proudly showing it to reporters during the ensuing years.

Guevara died on October 9th. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the vicinity of the execution site after the CIA had removed his hands to send to different parts of the world to verify his identity.

Also removed was Guevara’s diary, which outlined the guerrilla war being fought in Bolivia. It tells of the group being forced to begin operations due to discovery by the Bolivian Army, the eventual split of the group, and the general failure of the guerrillas. It shows the split between Guevara and the Bolivian Communist Party that resulted in Guevara having significantly fewer soldiers than originally anticipated. It shows that Guevara had a great deal of difficulty recruiting from the local populace, due mainly to the fact that the guerrilla group had learned quechua and not the local language. As the campaign drew to an unexpected close, Guevara became increasingly ill. He suffered from asthma, and most of his last offensives were carried out to obtain medicine.

The Bolivian Diary was quickly and crudely translated by Ramparts magazine and circulated around the world. Fidel Castro has denied involvement with this.

From the group of 27 guerrillas that set out on February 1, 1967, only 3 survived after October 9, 1967. They crossed the Andes Mountains into Chile. There, they were met by Salvador Allende, who granted them asylum and helped them return to Cuba.

In 1999, the skeletal remains of Guevara’s body were exhumed, positively identified by DNA matching and returned to Cuba, where he is revered as a heroic revolutionary leader. This reverence owes more to good PR in the years following his death (or ‘martyrdom,’ as some would have it) than to his actual achievements.

Che’s book, Guerrilla Warfare, was seen for a time as the definitive philosophy for fighting irregular wars. However, with his death in Bolivia his “Cuban Style” of revolution outlined in the book was thought by some to be ineffective. Guevara believed that a small group (foco) of guerrillas, by violently targeting the government, could actively ferment revolutionary feelings among the general populace, so that it was not necessary to build broad organizations and advance the revolutionary struggle in measured steps before launching armed insurrection.

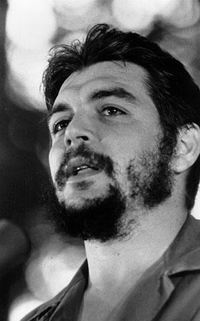

In the late 1960s, he became a popular icon for revolution and youthful political ideals in Western culture. A dramatic photograph of Che taken by photographer Alberto Korda in 1960 soon became one of the century’s most recognizable images, and the portrait was simplified and reproduced on a vast array of merchandise, such as T-shirts, posters, and baseball caps.

Major works of Che Guevara

– Guerrilla warfare

– On Vietnam and world revolution

– Che Guevara speaks; selected speeches and writings – Edited by George Lavan

– Open new fronts to aid Vietnam!

– Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War

– The diary of Che in Bolivia, November 7, 1966 – October 7, 1967\

– Episodes of the Revolutionary War

– The speeches and writings of Ernesto Che Guevara – Edited, annotated, and with an introd. by John Gerassi

– Socialism and man in Cuba

Great post but I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Thank you!

Wspaniałe pomysły kosztuja grosze. Bezcenni sa ludzie, ktorzy je urzeczywistniaja. Twoj blog jest tego wspaniałym przykładem…