The two food organizations also differed in the extent to which they met the determinants of effective resolution of interdepartmental conflict. In beginning a discussion of these differences, we should re-emphasize the point made in the last chapter, that the low-performing food organization was rapidly improving its performance. As we compare it here with the high- performing organization, we shall see some evidence that progress was also being made in developing more effective practices for handling interdepartmental conflict.

1. Integrating Devices

One step that had recently been taken to improve the reso- lution of interdepartmental conflict in the low-performing or- ganization was the establishment of an integrating department. The members of this unit were charged with integrating the product-innovation efforts of the production, sales, marketing, and research departments. In the high-performing organization no integrating department had been established. Instead, individual integrators in the research and marketing departments had formal responsibility for reaching joint decisions. In addition, this organization placed a great deal of reliance on direct contact among the various unit managers. As we shall see, these integrating devices in the high-performing organization were more effective than those in the low performer, but managers in the less successful organization’s integrating unit were learning to perform their function and seemed to be improving their abilities to handle disagreements.

2. Determinants of Effective Conflict Resolution

In this discussion we want first to examine the factors that were directly related to the behavior of only the integrators in these two organizations. In both organizations these men | had relatively balanced orientations and ways of thinking. U- They were concerned not only with the important market factors in decisions, but also, to an almost equal extent, with the scientific and techno-economic factors. Their time orientations were also balanced between the relatively short-term concerns of production and sales and the longer- term orienta- [ tion of research and marketing personnel. In both organizations these integrators also felt that they were being rewarded most importantly for the performance of the product group with which they were associated. Thus in these two determinants of effective conflict resolution there were no meaningful differences between the managers primarily involved in integration.

Managers in the high-performing organization saw the in- dividual integrators as having more influence on interdepart- mental decisions than their departmental colleagues in research and marketing. In the low-performing organization members of the integrating department were seen as having influence equal to that of the members of the research and marketing units. The basis of this influence did, however, differ somewhat in these two organizations, and this factor seemed to affect the relative ability of the integrators to resolve conflicts. In the high- performing organization the influence of these integrators was seen as stemming directly from their ability and knowledge. Comments such as the following were typical:

When I come up with a product, I take it over to [an in- tegrator] and say, “Look here, taste it,’’ and I pray that he is going to like it. I don’t know what good [product] tastes like, and I have come to the conclusion that nobody else in the company knows what it tastes like. However, fortunately we have a guy like [integrator] who is a 30-year expert, and who can judge what this thing should taste like. If he says it is mushy, it is mushy, and I go back and work some more, but hell, I couldn’t identify what mushy was from anything else.

The basis of influence of the integrating department in the low- performing organization was not so clear. Some members of the organization seemed to feel that the influence of the integrators was derived from their close proximity to the chief executive. As one manager put it:

I think it is important to recognize that the [integrating] department here is an extension of the president, and it really helps him to do a lot of things he wants to do. . . .

Other managers seemed to feel that the integrating group’s influence stemmed from the competence of its members. As a member of the marketing department said:

That [integrating] group, their influence goes far beyond the description in the organization chart. [The unit’s man- ager] by nature is a hell of a good marketing man and very experienced in the food business. Consequently, the influ- ence of him and his group extends way beyond the normal boundary.

A comment from a production manager indicates the view that was perhaps most typical. He indicated that he and his colleagues were gaining confidence in the ability of the integrating group:

All of us in production are steamed up by the reorganiza- tion of this [integrating unit] and feel we needed this reor- ganization. We just completed the best year in our history, and I think much of it stems from that fact.

The conclusion we drew from these data was that, while at its inception the integrating group was seen as deriving its in-fluence from its proximity to the chief executive, gradually, as it achieved some success in tying together the efforts of other units, its members were beginning to develop a reputation for their expertise. To the extent that the other managers still felt that their influence was derived from their positions, their effectiveness at resolving interdepartmental conflict was somewhat limited, but this situation was improving.

Turning to the determinants affecting the ability of all the members of the organization to handle conflict effectively, we shall first examine the relative influence of the basic departments in each organization. In both organizations we found that the marketing and research groups had significantly higher influence than production (Table V—4). This was consistent with the dominant issue of innovation, which required that the inputs from the market and scientific sectors be combined to develop successful new products. In the high-performing organization, however, members of both of these units had significantly higher influence than their opposite numbers in the competing organization.

Thus it is not surprising that the total influence in the high- performing organization was significantly higher than in the low-performing organization (Table V-5). To interpret this difference in total influence properly, we must first examine another factor that affected their relative capacity for dealing with interdepartmental disputes.

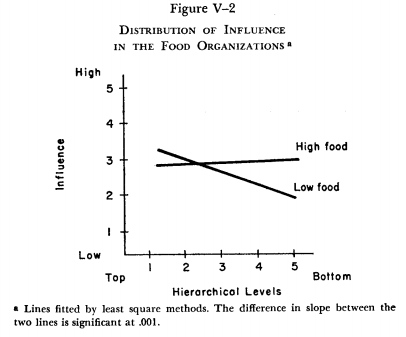

The two organizations differed in respect to the level at which influence was concentrated (Figure V-2). As we have pointed out, given the uncertainty of knowledge, particularly in the market and scientific sectors of this environment, it seemed necessary for influence to be spread throughout all managerial levels if the managers who were attempting to resolve interdepartmental conflict were to have the knowledge required to do so. In the low- performing organization influence was not evenly spread, but was concentrated in the higher levels. This was especially true at the top of the research hierarchy. Research scientists expressed considerable concern about this fact, indicating that it reduced their ability to become involved in settling interdepartmental problems.

One research scientist expressed this widespread concern:

In many ways I think this is very frustrating. The scientist calls all the development shots until he comes up with an interesting project. Then you lose touch. All of a sudden the thing is taken out of your hands, and you really don’t know what is going on in terms of the meaningful decisions that affect the thing you are working on. A lot of decisions are made which affect your work. For instance, on the concept of advertising. However, you only get this information by faith.

You are not tied in. The information is going much higher up, even above the research group manager. I think we should certainly be included in the communication. Now many times the information doesn’t filter down to us — information which vitally affects our work.

Not only did this influence pattern create frustration for the working scientists, but it also meant that the research managers involved in decisions did not have available the detailed knowledge they needed. This same difficulty was evident to a lesser extent in the marketing function. Here too influence was concentrated at a level higher than the managers who had the detailed knowledge of markets required for decisions. As we have seen in looking at the organizations in other environments, this lack of congruence between knowledge and influence increased the difficulties involved in re-solving interdepartmental conflicts. It suggests again that the differences in total influence mentioned above are another manifestation of the lack of congruence between knowledge and influence. We might point out that the top managers in the low- performing organization were aware of this situation and were working to find methods of spreading the decision making throughout the organization.

Once more the final determinant of effective conflict resolution that we shall examine is the typical mode of behavior used to resolve conflict. Confrontation was more typical in the low- performing organization than in the more successful one (Table V-6). In the other modes of handling conflict the two organizations were similar. Although confrontation was more typical in the low performer, the high-performing organization was doing as much confronting and problem solving as the most effective plastics and container organizations. Since both food organizations compared favorably with all the other organizations in the study, this suggests that the reliance on confrontation should have facilitated the resolution of conflict in both organizations.

While both organizations met this determinant, the differences in the other factors mentioned affected their relative capacity to resolve conflicts and reach interdepartmental decisions. The influence of integrators in the high-performing organization was more clearly based on their competence and expertise than that of the integrators in the low performer. Members of the two functional departments most centrally involved in product innovation (marketing and research) had more influence in the high-performing organization than in the low performer. Finally, the hierarchical pattern of influence was less steep in the high-performing organization than in the low performer. This meant that in the more effective organization managers who had the influence to make decisions and resolve conflicting points of view also had the detailed knowledge of market, scientific, and technical factors required. This was not so clearly the case in the low-performing organization.

Again we have found that the differences in the extent to which two organizations met the determinants for effective conflict resolution help us to understand why the high-performing organization was achieving states of differentiation and integration that more nearly met the demands of its environment than those of its rival. The high-performing food organization, because its managers were dealing with conflict in a way that was consistent with the demands of the environment, was able to achieve both more effective integration and a higher degree of differentiation than its less successful competitor.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.