1. Integrative Devices

Only the low-performing container organization had a formal integrating unit. This department, which reported to the general manager, had as its assigned function the integration of sales requirements and production capacity at the organization’s several plants. In addition, the responsibility for scheduling decisions involving any one plant had been assigned to the individual plant managers and their counterparts in the sales department (the regional sales managers). As the reader may well suspect, these arrangements led to considerable confusion about where conflicts were to be resolved. We shall shortly explore this problem in more detail.

In the high-performing container organization all integration was carried out through the managerial hierarchy. No special departments, teams, or roles, other than a scheduling clerk, had been established to facilitate the process of conflict resolution. In this sense this company approached the proto-type of the classical organizational model, where all decisions should be made through the formal hierarchy. As we examine the determinants of effective conflict resolution in these two organizations, we shall see how this particular model fitted the requirements of this relatively stable and homogeneous environment.

2. The Determinants of Effective Conflict Resolution

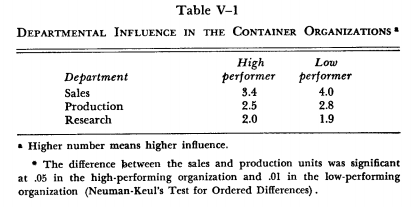

The first factor that seemed to determine each of these or- ganization’s capacity to handle interdepartmental conflict was the relative influence of the various departments. In both companies the sales and production departments apparently had the highest influence, and the former was significantly more influential than the latter (Table V-l) .* Generally this was consistent with the demands of the environment since both departments had to be involved in the crucial scheduling decisions and since it was the sales department that had close contact with the customer and had to initiate scheduling demands on production. We predicted, however, that if this inequity in influence became too large, the production people might feel that their point of view was not being given sufficient attention. If this happened, conflicts would be more difficult to resolve constructively.

In the high-performing organization, where this inequity was smaller than in the low performer, the production managers indicated that they felt their problems of plant scheduling were given sufficient attention. This may have been partially because, as we shall see, most of these decisions were made by upper management, who were seen as knowledgeable in both plant and markets matters.

In the low-performing organization, however, the imbalance of influence between production and sales was larger, and production managers indicated a dissatisfaction with their ability to influence decisions.* Two quotations from production managers will illustrate this point:

Scheduling is now a nip-and-tuck game with sales, and as far as I am concerned sales runs the plant. For example, if they want their items next week, we just have to do it; that’s the way the game is played around here.

* * * * *

I believe more time should be spent by salesmen in the plant and in the office. I think they ought to make regular visits to see our problems. They don’t appreciate our prob- lems. Of course, the salesman’s job is to take care of the customer, so they do everything they can to see that the product is made and put in stock, so the customer can get it whenever he wants it. However, they don’t seem to realize the problems this creates in the plants. More visits and more contact would improve this greatly.

As these comments suggest, production managers in the low- performing organization felt that they had too little influence over decisions. This imbalance in influence seemed to reduce the effectiveness of integration between the two units which had the knowledge needed to resolve the important in- terdepartmental conflicts around issues of customer service.

The second determinant of effective conflict resolution that we explored was the total influence of all members of the or- ganization. Based on our findings in the plastics industry, we would expect that the total influence would be greater in the high- performing organization than in the low-performing one, but this turned out not to be the case (Table V-2) . The managers in the low-performing organization actually felt that they had significantly more influence on decisions than did those in the high-performing company.

According to our earlier findings, this high total influence would suggest that the managers in the low-performing container organization should be able to work more effectively together in resolving interdepartmental conflicts. However, in extrapolating this conclusion from the plastics organizations to the container industry, we are generalizing about the one best organizational form without recognizing the differences in environmental demands in the two industries. In the plastics organizations the middle-level and lower-level managers had the knowledge required to make effective decisions, but in the container industry much of the required knowledge rested only at the upper levels of the three basic departments. While the managers in the low- performing container organization may have felt that they had important influence over decisions, they did not have the knowledge nec-essary to participate effectively in resolving conflicts and reaching these decisions.

The reader will recall that in discussing this matter of total influence in the plastics companies we offered two possible reasons why high total influence could contribute to effective conflict resolution and performance: by improving managerial motivation, or by improving the quality of decisions as the relevant knowledge was brought to bear. Now the evidence from the container companies would indicate that the latter explanation is the more valid. Having the knowledgeable people exert the influence seems to contribute to the quality of conflict resolution, even though it depresses the total influence. This is not to say that it might not also have a lesser side effect in depressing motivation. More will be said about this below.

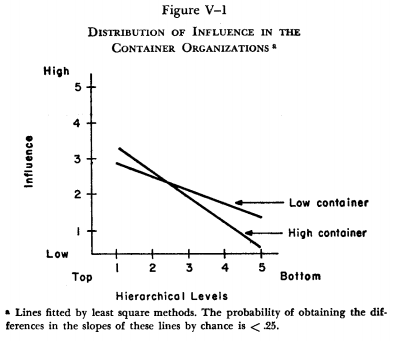

A clearer understanding of the influence pattern in these two organizations can be gathered from our findings about another determinant of effective conflict resolution—the management level at which influence to resolve conflict was concentrated. In the high-performing container organization the influence seemed to be more concentrated near the top of the hierarchy (Figure V— 1). Although the difference in the slope of the lines was not statistically significant, in the low-performing organization the influence line tended to be less steep and influence seemed to be somewhat more evenly distributed. This finding, together with the data on total influence, suggests that while the managers in the high-performing organization generally felt that they had less influence to resolve conflicts, those executives who were seen as having high influence were the top managers, who had the requisite knowledge to make decisions. We are not suggesting that the lower and middle managers in the high-performing container organization were not involved in any decisions. Our interviews indicated that they were particularly concerned with resolving technical and quality problems. So the data suggest that they did have some influence in resolving conflicts, though less than their counterparts in the low- performing organization.

These differences between the two organizations are even ! more dramatically illustrated by the tone of comments from managers about the level at which conflicts were resolved. In I the low-performing organization there had been a systematic attempt, as we have mentioned, to get lower and middle man- agers involved in making decisions about scheduling and other customer-service issues. While this apparently gave them more feeling of having influence over these decisions than managers had in the high-performing organization, it also left them with a feeling of frustration because they were not able to achieve any clear resolution. As one production manager said:

Presently there are thousands of guys involved in the scheduling process around here. It just doesn’t work with so many cooks in the stew What happens now is that when an order comes in it is my decision to take care of it and to schedule it into the first available production space and then give some other orders a later production date. This date usually goes back to the sales office, and they aren t happy, and they will start for the regional manager or the [integrating department] in headquarters to try to get this date improved. Consequently, the [integrating] guys are al- ways dabbling with us about the schedule. This really gets frantic sometimes. On the other hand, there has to be a bit of this in the situation we are in. Hell, I don’t know all the facts out here [in an outlying plant]. It is just an order, and we don’t know what’s behind it or how important it is to the company. This, I think, also accounts for a lot of meddling in the scheduling.

This manager was pointing to the central problem in his organization. The middle-level managers, who were being asked to get involved in resolving scheduling conflicts, did not know enough about plant capacities and customer requirements to make these interdepartmental decisions. As a consequence, the decisions of the regional and plant managers were frequently reversed by the integrating department or, more often, by higher headquarters management. The comment of one salesman describes the dilemma of the regional manager:

My boss, the regional manager, is doing an impossible task. And in fact, what he has been turned into is a production scheduler. He is so swamped with these petty problems that he hasn’t made a call with us on customers in weeks. What really happens is that we get one direction from the regional manager and another from the home office, and when we ask the regional manager about it, all he is able to say is that they double-crossed him. . . .

Although this salesman did not know who finally made these decisions, there was little doubt among the managers at the organization’s headquarters that conflicts were eventually resolved by the top departmental managers and the general manager. Even though the middle executives began by trying to resolve the conflicts and make decisions, they found that they were not effective because of a lack of information about the total situation. Thus conflicts were sent up the organizational ladder, past the integrating department, to the upper echelon, where adequate knowledge to make decisions was available. The managers at the middle levels were frustrated by their inability to handle these conflicts as they had been led to believe they should, and the problems intensified and festered as they were passed upward.

In contrast to this situation, interviews with managers in-dicated, as the influence data (Figure V-l) suggested, that in the high-performing organization the influence to resolve conflict was more concentrated at the upper levels. From talking to the managers at all levels in the organization, we could clearly see who made crucial interdepartmental scheduling decisions. It was the chief executive officer, with the help of other principal officers. These men had the required knowledge about the total situation, and they maintained almost complete control over all scheduling decisions. A production executive described the chief executive’s involvement in this way:

In actuality, of course, in this business we are dealing with a balance so delicate that you must be in a high position to appreciate all the factors involved [The chief executive officer] does all the scheduling in his head, and then tells us what to do. He has scheduling meetings weekly, and then others sit in as a data source. Scheduling is definitely regarded in the sales area. It is not a production thing, and this is a primary consideration. Almost no decisions in this area are production decisions. They don’t give production considéra-tion unless you can’t produce something they want to do. This is not to say, though, that sales is unconscious of pro- duction problems. Production doesn’t sit in on the meetings, though. However, most people who are there are aware of the problems of producing containers and of the plant ca- pacities, so the production interests are not absent, even if the people are not there.

We should also note that this manager and his production department colleagues felt that their interests were well rep- resented in the resolution of conflict by the top executives. This is related to the point made earlier about the relative influence of the sales and production departments in this organization.

One of the top sales executives, who was directly involved in the scheduling decisions, described the process by which they were reached:

The assignment of the machine schedules is worked out by myself, the sales vice president and [the chief executive], who will sit down to figure this out. We do this at least once a week. What we work at is to recap every item we know of at the present time by product and customer. We sit down to do this once on Mondays, and then throughout the week, as something arises, we will make changes. All day long this is going on, and [the chief executive] is in and out of here all day long. We keep him advised. He is usually talking to me at least two or three times a day.

A salesman’s comments provide another perspective on the chief executive’s role in the resolution of conflict:

On new customers the sales vice president tells me whether we can do the business. However, the real person is the chief executive, because he wants to be updated immediately on everything. He wants to be kept up to date on everything, and he does get himself involved in everything. He runs this place completely. And he gets fancy if something happens that he wasn’t aware of and wasn’t involved in. . . .

I thought at first when I came here this was meddling. However, now, as I think about it, at least you have a guy who is going to give you decisions. If I want answers quickly, I’ll go directly to him, keeping the other people tied in as I go. . . .

This salesman is also reflecting the common attitude among this organization’s personnel about the chief executive’s extreme control of decisions. While a few managers indicated that they were unhappy because of their own lack of involvement, the vast majority saw the situation as necessary and conducive to their effectively performing their own jobs. When conflicts arose, they knew that they would get them resolved by the top managers, who had both the knowledge of the environment and the influence required.

All these data, then, suggest that one important determinant of the high-performing organization’s ability to resolve conflict effectively was the centralization of influence. In the low- performing organization total influence was greater, and more managers felt that they were involved in trying to resolve conflicts. Since they lacked the knowledge to make decisions, however, their involvement in this process led primarily to frustration and increased conflict.

One other related factor that affected the conflict-resolving capacity of the high-performing organization was the basis of the influence of the chief executive and his top aides. While one might at first glance suspect that their high influence was based solely on their positions and the fact that they held the purse strings, this was not entirely the case. In interview after interview we heard unsolicited comments describing the chief executive as “a brilliant man”; “a man who knows more about this industry than anyone else”; etc. Similar comments were made about the other principal officers. These remarks, along with some cited earlier, which recognized top management’s unique position to have overall knowledge about industry conditions, suggest that the influence of top management was not derived from position alone, but also from knowledge and competence in dealing with industry problems. Although there is no evidence that the top executives in the low-performing organization did not seem competent to their subordinates, it is clear that they did not command the broad respect based on ability that the top management in the high- performing organization did. The fact that the chief executive and his management colleagues in the high-performing organization were seen as being so competent seemed to result in their decisions’ being accepted as sound by all parties to conflicts.

This matter of influence based on knowledge and competence was also connected to the relative ineffectiveness of the integrating unit in the low-performing organization. While managers in this unit seemed to have the balanced orientations required for them to be effective integrators, they, like the other middle-level managers, often lacked the necessary knowledge. Beyond this, they also lacked influence. As a manager in the integrating department put it:

The traditional method of resolving conflict in this com- pany is by taking it upstairs. This often cuts the legs off our own work. It spoils the effort we are making to create an impartial image as a referee. We are not the final authority. Either party can take the matter up further. We don’t have the authority to solve these problems at the lower levels.

If this integrating unit had been privy to the information required to make these decisions, and if it had, in the eyes of the functional managers, strong knowledge-based influence, it might have played a useful role. But these are big “if’s.” In fact, the unit was able to do little more than add further confusion to an already hectic situation.

A final factor related to our present discussion is the mode of behavior used to resolve conflict. In the high-performing organization there was significantly more confrontation than in the low-performing competitor (Table V-3). Judging from the pattern of hierarchical influence discussed above, much of the confrontation in the high-performing organization was apparently at the upper organizational levels. As we have suggested, however, many technical and quality problems were resolved at lower levels, again through the use of confrontation. These managers were apparently solving their conflicts and reaching decisions by openly examining different points of views. This difference between the high- and low-performing container organizations is consistent with our earlier findings in the plastics industry about the importance of confrontation of conflict for effective decision making.

In the high-performing container company (unlike the high- performing plastics organizations), we found less forcing and more smoothing than in the less successful competitor. However, the relatively large amount of smoothing in this high-performing organization is consistent with the point made earlier—that top executives did not appear to subordinates as capriciously using the power of their position to force compliance, but rather as competent persons using their knowledge to reach decisions. In fact, they seemed to be using smoothing as their back-up mode of handling conflict, perhaps as a way of maintaining good relations when they reached decisions that were particularly unpopular with any one functional unit. Contrary to what we saw in the plastics organizations, smoothing in this case may have been a useful secondary mode. The low-performing organization relied more on forcing. This, too, is consistent with our earlier discussion, which suggested that decisions were passed to higher levels of management, because these executives could reverse a decision that one lower functional manager considered unattractive, even though others saw it as desirable.

From the foregoing comparison we can understand how the high-performing organization was able to achieve better integration (although the same state of differentiation) than its less effective competitor. The more successful company had a better balance of influence between its sales and production units than the low performer. The pattern of hierarchical influence in the high- performing organization was also more consistent with the environmental demands than that in the low performer. Executives at the top of the high- performing organization had both the influence and the knowledge necessary to resolve conflicts, which was not the case in the low performer. We also found that the influence of the top managers in the high-performing organization was at least partially derived from their expertise and knowledge. While to some extent this may have been true in the case of the upper-level managers, in the low-performing organization it clearly was not true for the members of the integrating unit. As a result of their lack of influence and incomplete knowledge, these integrators were not effective in helping to resolve interdepartmental conflict. This suggests that in a stable environment when there is little differentiation among departments, special integrating units are not only redundant, but may actually add confusion. Finally, we found that in the high-performing organization managers were relying more on confrontation and problem-solving behavior as a way of handling conflict than were the managers in the other organization. As we suggested at the outset of this discussion, the high-performing organization fit the classical organizational model, with the influence to make integrating decisions resting heavily on the top managers. Now, however, we can see why this pattern of influence seemed to fit the demands of this fairly stable and homogeneous environment. The attempts to decentralize” influence in the low performer did not serve these particular environmental conditions so well.

We should, at this point, add a few words about some of the risks and costs associated with adopting this classical or- ganizational form. One important problem, about which the managers in the high-performing organization were concerned, is the matter of managerial succession. What happens when the chief executive retires or is away? Even given the fact that there were other capable managers in this organization, removing a manager with this omnipotence and omniscience would require a period of radical adjustment.

Second, as we suggested earlier, some managers in this or- ganization were concerned about their inability to influence decisions. While this was not a serious problem, it raises the important issue of the personality characteristics of managers who are attracted to this type of organization and can find satisfaction in it. We did not attempt systematically to study this issue, but it is worth noting that the reason that the low- performing organization had attempted to spread influence throughout the organization was so that its managers, particularly the younger ones, would be more involved in decisions. The top executives hoped that this would develop their managerial capacity and would make the company a more attractive place to work. Since this effort to decentralize decision making did not fit the organization’s environmental requirements, we might at least speculate whether the real problem in the low performer was the attempt to attract managers whose motivational and other personality characteristics did not fit the demands of the jobs available. While this study cannot provide answers to this sort of issue, this brief discus-sion does remind us of the necessity to consider not only the fit between the organization’s structure and its environment, but also the match between the structure and the predispositions of the members.

Source: Lawrence Paul R., Lorsch Jay W. (1967), Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Harvard Business School.