The grouping of positions and units is not simply a convenience for the sake of creating an organigram, a handy way of keeping track of who works in the organization. Rather, grouping is a fundamental means, to coordinate work in the organization. Grouping can have at least four important effects:

- Perhaps most important, grouping establishes a system of common supervision among positions and units. A manager is named for each unit, a single individual responsible for all its actions. And it is the linking of all these managers into a superstructure that creates the system of for- mal authority. Thus, unit grouping is the design parameter by which the coordinating mechanism of direct supervision is built into the structure.

- Grouping typically requires positions and units to share common The members or subunits of a unit share, at the very least, a common budget, and often are expected to share common facilities and equipment as well.

- Grouping typically creates common measures of performance. To the extent that the members or subunits of a unit share common resources, the costs of their activities can be measured jointly. Moreover, to the extent that they contribute to the production of the same products or services, their outputs can also be measured jointly. Joint performance measures further encourage them to coordinate their activities.

- Finally, grouping encourages mutual adjustment. In order to share resources and to facilitate their direct supervision, the members of a unit are often forced to share common facilities, thereby being brought into close physical proximity. This, in turn, encourages frequent informal con- tacts among them, which in turn encourages coordination by mutual adjustment.

Thus, grouping can stimulate to an important degree two important coordinating mechanisms—direct supervision and mutual adjustment— and can form the basis for a third—standardization of outputs—by providing common measures of performance. Unit grouping is, as a re- sult, one of the most powerful of the design parameters. (A prime charac- teristic of the two other coordinating mechanisms—standardization of work processes and of skills—is that they provide for the automatic coordi- nation of the work of individuals; as a result, they can be used indepen- dently of the ways in which positions are grouped.)

But for the same reason that grouping encourages strong coordina- tion within a unit, it creates problems of coordination between units. As we have seen, the communication is focused within the unit, thereby isolating the members of different units from each other. In the terms of Lawrence and Lorsch (1967), units become differentiated in their various orientations— in their goals, time perspectives, interpersonal styles of interaction, and degrees of formalization of their structures. For example, a production department might be oriented toward the goal of efficiency as opposed to that of creativity, have a short time perspective, exhibit an orientation to getting the job done rather than to the feelings of those who do it, and have a highly bureaucratic structure. In contrast, a research department may exhibit exactly the opposite characteristics on all four dimensions. Some- times this differentiation is reinforced by special languages used in the different departments; there are times when personnel in production and in research simply cannot understand each other.

The result of all this is that each unit develops a propensity to focus ever more narrowly on its own problems while separating itself ever more sharply from the problems of the rest of the organization. Unit grouping encourages intragroup coordination at the expense of intergroup coordi- nation. The management school that adopts a departmental structure soon finds that its finance professors are interacting more closely with each other but are seeing less of the policy and marketing professors, and all become more parochial in their outlook. Of course, this can also work to the advantage of the organization, allowing each unit to give particular attention to its own special problems. Earlier, we saw the example of the new venture team isolated from the rest of a bureaucratic structure so that it can function organically and therefore be more creative.

1. Bases for grouping

On what basis does the organization group positions into units and units into large ones? Six bases are perhaps most commonly considered:

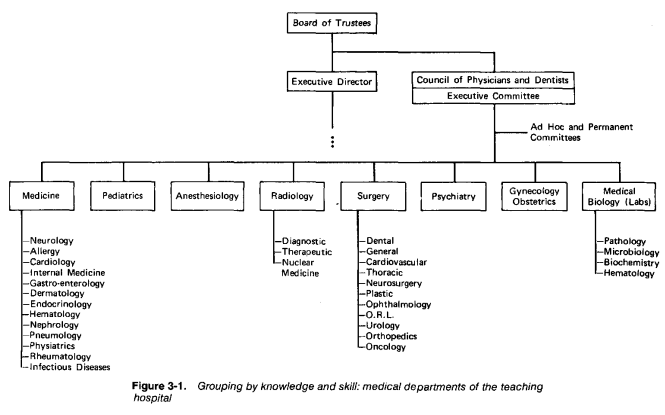

- Grouping by Knowledge and Skill. Positions may be grouped ac- cording to the specialized knowledge and skills that members bring to the Hospitals, for example, group surgeons in one department, anesthe- tists in another, psychiatrists in a third. Figure 3-1 shows the organigram for the medical component of a Quebec teaching hospital, with the physi- cians grouped by knowledge and skill in two tiers. Grouping may also be based on level of knowledge or skill; for example, different units may be created to house craftsmen, journeymen, and apprentices, or simply skilled and unskilled workers.

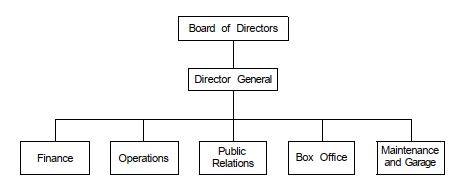

- Grouping by Work Process and Units may be based on the process or activity used by the worker. For example, a manufacturing firm may distinguish casting, welding, and machining shops, and a football team may divide into a line unit and a backfield unit for practice. Often, the technical system is the basis for process grouping, as in a printing shop that sets up separate letterpress and offset departments, two different processes to produce the same outputs. Work may also be grouped accord- ing to its basic function in the organization—to purchase supplies, raise capital, generate research, produce food in the cafeteria, or whatever. Per- haps the most common example of this is grouping by “business func- tion”—manufacturing, marketing, engineering, finance, and so on, some of these groups being line and others staff. (Indeed, the grouping of line units into one cluster and staff units into another—a common practice—is another example of grouping by work function.) Figure 3-2 shows the organigram for a cultural center, where the grouping is based on work process and function.

- Grouping by Groups may also be formed according to when the work is done. Different units do the same work in the same way but at different times, as in the case of different shifts in a factory.

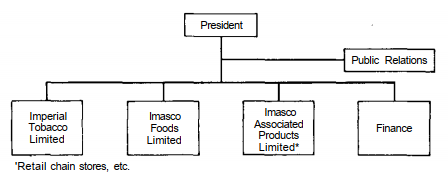

- Grouping by Output. Here, the units are formed on the basis of the products they make or the services they render. A large manufacturing company may have separate divisions for each of its product lines—one for chinaware, another for bulldozers, and so on. A restaurant may separate organizationally as well as spatially its bar from its dining facilities. Figure 3-3 shows the product grouping by divisions in Imasco, a Canadian con-glomerate firm (with two units—public relations and finance—based on function).

Figure 3-2. Grouping by work process and function: a cul- tural center

- Grouping by Client. Groups may also be formed to deal with differ- ent types of clients. An insurance firm may have separate sales depart- ments for individual and group policies; similarly, hospitals in some coun- tries have different wards for public and private patients.

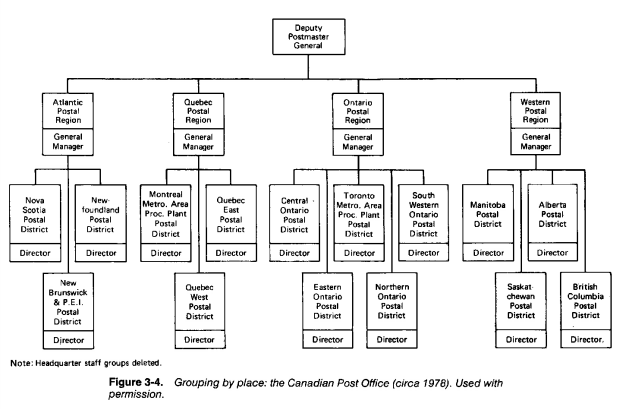

- Grouping by Place. Groups may be formed according to the geo- graphical regions in which the organization In May 1942, the U.S. War Department was organized in terms of seven “theaters”—North American, African Middle Eastern, European, Asiatic, Pacific, Southwest Pacific, and Latin American. On a less global scale, a bread company may have the same baking facility duplicated in twenty different population areas to ensure fresh daily delivery in each. Figure 3-4 shows another example of geographical grouping—in this case two-tier—in the super- structure of the Canadian Post Office. A very different basis for grouping by place relates to the specific location (within a geographic area) where the work is actually carried out. Football players are differentiated according to where they stand on the field relative to the ball (linemen, backfielders, ends); aircraft construction crews are distinguished by the part of the air- plane on which they work (wing; tail); and some medical specialists are grouped according to the part of the body on which they work (the head in psychiatry, the heart in cardiology).

Figure 3-3. Grouping by output: Imasco Limited (circa 1975). Used by permission.

Of course, like all nice, neat categorization schemes, this one has its own gray areas. Psychiatry was purposely included in two examples—one in grouping by place, the other in grouping by knowledge and skill—to illustrate this point. Consider, for example, the medical specialties of sur- gery and obstetrics. These are defined in the Random House Dictionary as follows:

- Surgery: the act, practice, or work of treating diseases, injuries, or deformities by manual operation or instrumental appliances.

- Obstetrics: the branch of medical science concerned with childbirth and caring for and treating women in or in connection with childbirth.

These definitions are not consistent in our terms. Obstetrics is de- fined according to client; surgery is defined according to work processes. A closer look indicates that even within a medical specialty, the basis for specialization can be ambiguous. Obstetricians may deal with particular clients, but they also use particular work processes, and their outputs are also unique to their grouping (namely, delivered babies); surgeons treat special kinds of patients and they also have their own distinct outputs (removed or replaced organs). In the same vein, so to speak, Herbert Simon points out that “an education department may be viewed as a purpose (to educate) organization, or a clientele (children) organization; the Forest Service as a purpose (forest conservation), process (forest man- agement), clientele (lumbermen and cattlemen utilizing public forests), or area (publicly owned forest lands) organization” (1957:30, 31).

The notion of grouping by process, people, place, or purpose (out- put) is, in fact, one of the pillars of the classical literature on organization design, and Simon devotes some of his sharpest criticism of the classical principles to it (pp. 28-35). He is especially severe on the “ambiguities” of the terms, arguing, as in the quotation above, that the same group can often be perceived in different ways.

A typist moves her fingers in order to type; types in order to reproduce a letter; reproduces a letter in order that an inquiry may be answered. Writing a letter is then the purpose for which the typing is performed; while writing a letter is also the process whereby the purpose of replying to an inquiry is achieved. It follows that the same activity may be described as purpose or process, (p. 30)

Simon’s basic point is that process and purpose are linked in a hierarchy of organizational means and ends, each activity being a process for a higher- order goal (typing a letter to answer an inquiry, manufacturing products to satisfy customers), and a purpose for a lower-order one (moving fingers to type a letter, buying machines to manufacture a product). In the same sense, the whole organization can be viewed as a process in society—police departments for protection so that the citizens can live in peace, food companies to supply nourishment so that people can sustain themselves.

It is interesting to note that Simon’s illustrations of ambiguities be- tween process and purpose in specific departments all come from organi- zations in which the operators are professionals. So, too, does our example of surgery and obstetrics. In fact, it so happens that their training differ- entiates the professionals by their knowledge and skills as well as by the work processes they use, which leads them to be grouped on these two bases concurrently. In professional organizations, clients select the profes- sionals on these bases as well. One does not visit a cardiologist for an ingrown toenail; students interested in becoming chemists do not register in the business school. In other words, in professional organizations such as hospitals, accounting firms, and school systems, where professional operators serve their own clients directly, grouping the operators by knowledge, skill, work process, and client all amount to the same thing.

But is that true in other organizations? The purchasing department in a manufacturing firm is far removed from the clients; it merely performs one of the functions that eventually leads to the products’ sale to the clients. Thus, it cannot be considered to be a client-based or output-based group. Of course, in Simon’s sense, it does have its own outputs and its own clients—purchased items supplied to the manufacturing department. But this example shows how we can clarify the ambiguity Simon raises: simply by making the context clear. Specifically, we can define output, client, and place only in terms of the entire organization. In other words, in our context, purpose is defined in terms of the purpose of the organization vis-a-vis its clients or markets, not in terms of intermediate steps to get it to the point of servicing clients and markets, nor in terms of the needs of the larger society in which the organization is embedded.

In fact, we shall compress all the bases for grouping discussed above to two essential ones: market grouping, comprising the bases of output, client, and place,1 and functional grouping, comprising the bases of knowl-edge, skill, work process, and function. (Grouping by time can be consid- ered to fall into either category.) In effect, we have the fundamental dis- tinction between grouping activities by ends, by the characteristics of the ultimate markets served by the organization—the products and services it markets, the customers it supplies, the places where it supplies them—or by the means, the functions (including work processes, skills, and knowl- edge) it uses to produce its products and services.

Each of these two bases for grouping merits detailed attention. But to better understand them, we must first consider some of the criteria organi- zations can use to group positions and units.

2. Criteria for grouping

We can isolate four basic criteria that organizations are able to use to select the bases for grouping positions and units: interdependencies related to the work flow, the work process, the scale of the work, and the social relationships around the work.

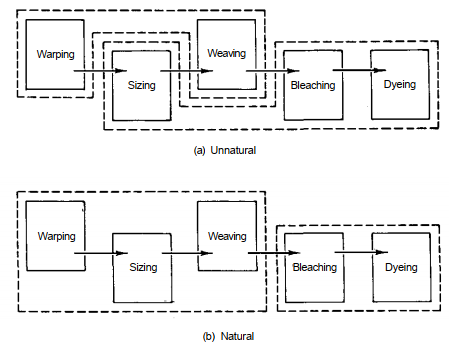

1. Work-Flow Interdependencies. A number of studies that have focused on the relationships among specific operating tasks stress one conclusion: grouping of operating tasks should reflect natural work-flow interdependencies. In Figure 3-5, for example, we have one writer’s view of “natural” and “unnatural” grouping in a sequential manufacturing pro- cess in an Indian weaving mill. Grouping on the basis of work-flow inter- dependencies creates what some researchers call a “psychologically com- plete task.” In the market-based grouping, the members of a single unit have a sense of territorial integrity; they control a well-defined organiza- tional process; most of the problems that arise in the course of their work can be solved simply, through their mutual adjustment; and many of the rest, which must be referred up the hierarchy, can still be handled within the unit, by that single manager in charge of the work flow. In contrast, when well-defined work flows, such as mining a coal face or producing a purchase order, are divided among different units, coordination becomes much more difficult. Workers and managers with different allegiances are called upon to cooperate. Since they often cannot, problems must be han- dled higher up in the hierarchy, by managers removed from the work flow. James Thompson puts some nice flesh on the bones of these con- cepts, describing how organizations account for various kinds of interde- pendencies between tasks. Thompson discusses three basic kinds of inter- dependence: pooled, involving only the sharing of resources; sequential, where the work is fed from one task to the next; and reciprocal, where the work is passed back and forth between tasks. Thompson claims that orga- nizations try to group tasks so as to minimize coordination and commu-nication costs. Since reciprocal interdependence is the most complex and hence the most costly, followed by sequential, Thompson concludes:

The basic units are formed to handle reciprocal interdependence, if any. If there is none, then the basic units are shaped according to sequential interde- pendence, if any. If neither of the more complicated types of interdepen- dence exists, the basic units are shaped according to common processes [to facilitate the handling of pooled interdependence]. (1967: 59)’

Figure 3-5. “Natural” and “unnatural” grouping in a weaving mill according to work flow (from Miller, 1959:257)

The question of grouping does not, however, end there, because “residual” interdependencies typically remain: one grouping cannot con- tain all the interdependency. This must be picked up in higher-order groupings, thus necessitating the construction of a hierarchy. And so, “The question is not which criterion to use for grouping, but rather in which priority are the several criteria to be exercised” (p. 51). Thompson’s answer is, of course, that the organization designs the lowest-level groups to contain the major reciprocal interdependencies; higher-order groups are then formed to handle the remaining sequential interdependencies, and the final groups, if necessary, are formed to handle any remaining pooled interdependencies.

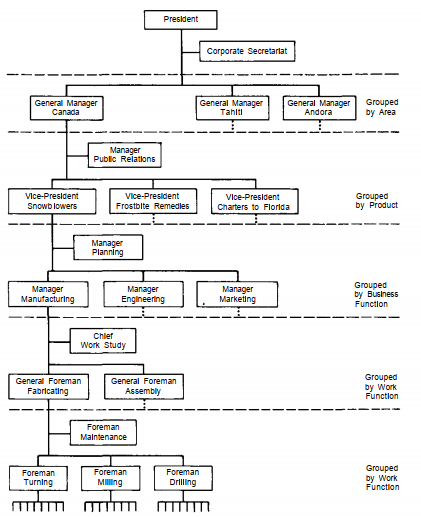

Figure 3-6 illustrates this with a five-tier hierarchy of an apocryphal international manufacturing company. The first and second groupings are by work process, the third by business function, the fourth by output (product), and the top one by place (country). (Staff groups are also shown at each level; these will be discussed later in the chapter.) The tightest interdependencies, reciprocal in nature, would be between the turning, milling, and drilling departments in the factory. The next level contains the sequential interdependencies from fabricating to assembly. Similarly, the level above that, largely concerned with product development, contains important sequential interdependencies. In mass production, typically, the products are first designed in the engineering department, then produced in the manufacturing department, and finally marketed by the marketing department. Above this, the interdependencies are basically pooled: For the most part, the product divisions and the national subsidiaries are inde- pendent of each other except that they share common financial resources and certain staff support services.

2. Process Interdependencies. Work-flow interdependencies are not, of course, the only ones to be taken into consideration by the designer of organization structure. A second important class of interdependence re- lates to the processes used in the work flow. For example, one lathe operator may have to consult another, working on a different product line (that is, in a different work flow), about what cutting tool to use on a certain job.

In effect, we have interdependencies related to specialization, which favor functional grouping. Positions may have to be grouped to encourage process interactions, even at the expense of work-flow coordination. When like specialists are grouped together, they learn from each other and be- come more adept at their specialized work. They also feel more comfort- able “among their own,” with their work judged by peers and by manag-ers expert in the same field.

3. Scale Interdependencies. The third criterion for grouping relates to economies of scale. Groups may have to be formed to reach sizes large enough to function efficiently. For example, every department in the fac- tory requires maintenance. But that does not necessarily justify attaching one maintenance man to each department—in effect, grouping him by work flow. There may not be enough work for each maintenance man. So a central maintenance department may be set up for the whole factory.

This, of course, encourages process specialization: whereas the main- tenance man in each department would have to be a jack of all trades, the one among many in a maintenance department can specialize, for exam- ple, in preventive maintenance. Similarly, it may make economic sense to have only one data-processing department for the entire company, so that it can use a large, efficient computer; data-processing departments in each division might have to use smaller, less efficient ones.

Figure 3-6. Multiple levels of grouping in a multinational firm

This issue—essentially of the concentration or dispersal of services— arises in a great many contexts in the organization. Should secretaries be grouped into typing pools or assigned to individual users; should the university have a central library or a series of satellite ones attached to each faculty; should the corporation have a single strategic planning group at headquarters or one attached to each division (or both); should there be a central telephone switchboard or a centrex system, allowing the public to dial directly inside the organization? The issue lends itself well to mathe- matical formulation and has been so treated in some of the literature (for example, Kochen and Deutsch, 1973). We shall return to this issue shortly.

4. Social Interdependencies. A fourth criterion for grouping relates not to the work done but to the social relationships that accompany it. One study in coal mines (Trist and Bamforth, 1951) showed clearly the impor- tance of these social factors. Workers had to form groups to facilitate mutu- al support in a dangerous environment. To use a favorite term of the well- known British Tavistock Institute, the system was sociotechnical.

Other social factors can enter into the design of units. For example, the Hawthorne studies suggested that when the work is dull, the workers should be close together, to facilitate social interaction and so avoid boredom. Personalities enter the picture as well, often as a major factor in organizational design. People prefer to be grouped on the basis of “getting along.” As a result, the design of every superstructure ends up as a com- promise between the “objective” factors of work flow, process, and scale interdependency, and the “subjective” factors of personality and social need. Organigrams may be conceived on paper, but they must function with flesh-and-blood human beings. “Sure, the sales manager should re- port to the area superintendent. But the fact is that they’re not on speaking terms, so we show him reporting to the head of purchasing instead. It may seem screwy, but we had no choice.” How often have we heard such statements? Scratch any structure of real people and you will find it loaded with such compromises.

In many cases, “getting along” encourages process specialization. Specialists get along best with their own kind, in part because their work makes them think alike, but also, perhaps more importantly, because in many cases it was common personality factors that caused them to choose their specialties in the first place. The extroverts seek out marketing or public relations, the analytic types end up in the technostructure. Some- times it is best to keep them apart, at least on the organigram.

These four criteria—work flow, process, scale, and social interdepen- dencies—constitute the prime criteria organizations use to design units. Now let us see how these apply to the functional and market bases for grouping.

3. Grouping by function

Grouping by function—by knowledge, skill, work process, or work func- tion—reflects an overriding concern for process and scale interdependen- cies (and perhaps secondarily for social interdependencies), generally at the expense of those of the work flow. By grouping on a functional basis, the organization can pool human and material resources across different work flows. Functional structure also encourages specialization—for exam- ple, by establishing career paths for specialists within their own area of expertise, by enabling them to be supervised by one of their own, and by bringing them together to encourage social interaction. Thus, one re- searcher found in a detailed study of thirty-eight firms working on U.S. government R&D contracts that “while the existence of project [market- based] teams increased the likelihood of meeting cost and time targets, the presence of a strong functional base was associated with higher technical excellence as rated by both managers and clients” (Knight, 1976:115-16).

But these same characteristics indicate the chief weaknesses of the functional structure. The emphasis on narrow specialty detracts from at- tention to broader output. Individuals focus on their own means, not the organization’s broader ends. Moreover, performance cannot easily be mea- sured in the functional structure. When sales drop, who is at fault: market- ing for not pushing hard enough, or manufacturing for shoddy workman- ship? One will blame the other, with nobody taking responsibility for the overall result. Someone up above is supposed to take care of all that.

In effect, the functional structure lacks a built-in mechanism for coordinating the work flow. Unlike the market structures that contain the work-flow interdependencies within single units, functional structures im- pede both mutual adjustment among different specialists and direct super- vision at the unit level by the management. The structure is incomplete; additional means of coordination must be found.

The natural tendency is to let coordination problems rise to higher- level units in the hierarchy, until they arrive at a level where the different functions in question meet. The trouble with this, however, is that the level may be too far removed from the problem. In our Figure 3-6, for example, a problem involving the functions of both drilling and selling (perhaps a request by a customer to have a special hole drilling on his snowblowers for rear-view mirrors) would have to rise three levels to the vice-president in charge of snowblowers, the first person whose responsibilities involve both functions.

Of course, functional structures need not rely on direct supervision for coordination. These are specialized structures; where their jobs are unskilled, they can rely on formalization to achieve coordination. Thus, we can conclude that the functional structures—notably, where the operating work is unskilled—tend to be the more bureaucratic ones. Their work tends to be more formalized, and that requires a more elaborate admin- istrative structure—more analysts to formalize the work, and higher up the hierarchy, more managers to coordinate the work across the functional units. So some of the gains made by the better balancing of human and machine resources are lost in the need for more personnel to achieve coordination.

To put this issue the other way around, bureaucratic structures (with unskilled operators) rely more extensively on the functional bases for grouping. That is, they tend to be organized by the function performed rather than the market served. (And where there are many levels of group- ing, they tend to be organized on functional bases at higher levels in the hierarchy.) In seeking, above all, to rationalize their structures, such bu- reaucracies prefer to group according to the work processes used and then to coordinate by the formalization of work, involving the proliferation of rules. This way, on paper at least, all relationships are rationalized and coherent.

4. Grouping by market

Lawrence and Lorsch provide us with an interesting illustration of the advantages of market grouping. They reproduce a memo from an advertis- ing agency executive to his staff describing the rationale for a conversion from a functional structure (based on copy, art, and TV departments) to one of the market groups:

Formation of the “total creative” department completely tears down the walls between art, copy, and television people. Behind this move is the realization that for best results all creative people, regardless of their particular specialty, must work together under the most intimate relationship as total advertising people, trying to solve creative problems together from start to finish.

The new department will be broken into five groups reporting to the senior vice president and creative director, each under the direction of an associate creative director. Each group will be responsible for art, television, and copy in their accounts. (1967:37)

In this case, market-based grouping is used to set up relatively self- contained units to deal with particular work flows. Ideally, these units contain all the important sequential and reciprocal interdependencies, so that only the pooled ones remain: each unit draws its resources and per- haps certain support services from the common structure and in turn con- tributes its surpluses or profits back to it. And because each unit performs all the functions for a given set of products, services, clients, or places, it tends to identify directly with them, and so its performance can easily be measured in these terms. Markets, not processes, get the employees’ un- divided attention. And, of course, with the necessary mutual adjustment and direct supervision contained right inside the unit, the organization need rely less on formalization for coordination, and so tends to emerge as less bureaucratic.

But with the focus on coordination across specialties, there is, of course, less process specialization. Compare, for example, these two bases for grouping in a retail company, say, in hardware. The company can build one large downtown store that sells everything imaginable, organizing itself on the basis of specialist departments. In contrast, it can set itself up as a retail chain, a market-based structure with small stores throughout the city. In search of special items for his nail sculptures, the customer in the large, specialized store would simply find the nail department and seek out a salesperson there who could tell him if copper roofing nails with crosshatched heads were available in the five-centimeter size or only in the seven-centimeter size. Should the nail sculptor find himself in the smaller branch store, almost certainly more conveniently located, he would proba- bly find no copper nails of any kind in stock—or any salesperson who could distinguish copper nails from brass-plated ones. But the salesperson in the chain store could better tell him where to find a hammer.

In general, the market structure is a less machinelike structure, less able to do a specialized or repetitive task well. But it can do more tasks and change tasks more easily, its essential flexibility deriving from the fact that its units are relatively independent of each other. New units can easily be added and old ones deleted. Any one store in a retail chain can easily be closed down, usually with little effect on the others. But closing down one specialized department in a large store may bankrupt it. There are chain stores that sell only bread or cheese, but there is no supermarket that can afford to dispense with either.

The market basis for grouping is, however, no panacea for the prob- lems of organizational design. We can see this most clearly in a study by Kover (1963-64). He, too, looked at an advertising agency that re- organized, in virtually the same way as the one cited earlier. But Kover found effects not mentioned above: Specialists had much less communica- tion with colleagues in their own functions and even with the clients (com- munication with them now being restricted largely to the managers of the market units); their sense of professional worth diminished, in part be- cause their work was judged by general managers instead of their specialist peers. Those who saw themselves as craftsmen became increasingly dissat- isfied with their work and alienated from the firm; many, in fact, left within a year of the reorganization. In effect, the market-based structure detracted from an emphasis on specialization, apparently with a resulting decrease in the quality of the specialized work.

The market structure is also more wasteful of resources than the functional one—at the lowest unit level if not in the administrative hier- archy—since it must duplicate personnel and equipment or else lose the advantages of specialization.

.. . if the organization has two projects, each requiring one half-time elec- tronics engineer and one half-time electromechanical engineer, the pure proj- ect [market] organization must either hire two electrical engineers—and re- duce specialization—or hire four engineers (two electronics and two electromechanical)—and incur duplication costs. (Galbraith; 1971:30)

Moreover, the market structure,_ because of less functional specializa- tion, cannot take advantage of economies of scale the way the functional structure can. The large hardware store can perhaps afford a lift truck at its unloading dock, whereas the small one cannot. Also, there may be waste- ful competition within the market structure, as, for example, when stores in the same chain compete for the same customers.

What all this comes down to is that by choosing the market basis for grouping, the organization opts for work-flow coordination at the ex- pense of process and scale specialization. Thus, if the work-flow interde- pendences are the significant ones and if they cannot easily be contained by standardization, the organization should try to contain them in a mar- ket-based grouping to facilitate direct supervision and mutual adjust- ment. However, if the work flow is irregular (as in a job shop), if standardization can easily contain work-flow interdependences, or if the process and scale interdependences are the significant ones (as in the case of organizations with sophisticated machinery), then the organization should seek the advantages of specialization and choose the functional basis for grouping instead.

5. Grouping in different parts of the organization

At this point it is useful to distinguish the first-order grouping—that is, individual positions into units—from higher-order grouping—units into larger units. The former, of course, pertains to the grouping of operators, analysts, and support staffers as individuals into their basic working units, and the latter pertains to the grouping of managers in order to build the formal hierarchy.

A characteristic of the first-order groupings is that operators, ana- lysts, and support staffers tend to be grouped into their own respective units in the first instance. That is, operators tend to form units with other operators, analysts with other analysts, and staff support personnel with other staff support personnel. (Obviously, this assumes that the organiza- tion is large enough to have a number of positions of each. An important exception to this—to be discussed later—is the case where a staff member is assigned as an individual to a line group, as for example when an accountant reports directly to a factory manager.) It is typically when the higher-order groups are formed that different operators, analysts, and sup- port staffers come together under common supervision. We shall elaborate on this point in our discussion of each of these groups.

The examples cited in this chapter have shown that positions in the operating core can be grouped on a functional or a market basis, depend- ing primarily on the importance of process and scale interdependences as opposed to those of the work flow. Assembly lines are market-based groups, organized according to the work flow, whereas job shops, because of irregular work flows or the need for expensive machinery, group their positions by work process and so represent functional groupings. And as we noted earlier, in operating cores manned by professionals, the func- tional and market bases for grouping are often achieved concurrently: The professionals are grouped according to their knowledge and skills and the work processes they use, but since their clients select them on these bases, the groups become, in effect, market-based as well.

Which basis for grouping is more common in the operating core? The research provides no definite answer on this question. But ours is a society of specialists, and that is most clearly manifested in our formal organiza- tions, particularly in their operating cores and staff structures. Thus, we should expect to find the functional basis for grouping the most common in the operating core.

There is, by definition, only one level of grouping in the operating; core—the operators grouped into units managed by the first-line super- visors. From there on, grouping brings line managers together and so builds the administrative superstructure of the middle line.

In designing this superstructure, we meet squarely the question that Thompson posed: not which basis of grouping, but rather in which order of priority? Much as fires are built by stacking logs first one way and then the other, so organizations are often built by varying the bases for group- ing units. For example, in Figure 3-6, the first grouping within the middle line is based on work process (fabricating and assembling), the next above on business function (engineering, manufacturing, and marketing), the one above that on market (snowblowers, and so on), and the last one on place (Canada, and so on). The presence of market-based groups in the upper region of the administrative hierarchy is probably indicative: anec- dotal evidence (published organigrams, and the like) suggests that the market basis for grouping is more common at the higher levels of the middle line than at the lower ones, particularly in large organizations.

As a final note on the administrative superstructure, it should be pointed out that, by definition, there is only one grouping at the strategic apex, and that encompasses the entire organization—all its functions and markets. From the organization’s point of view, this can be thought of as a market group, although from society’s point of view, the whole organiza- tion can also be considered as performing some particular function (deliv- ering the mail in the case of the post office, or supplying fuel in the case of an oil company).

Staff personnel—both analysts and support staff—seem, like wolves, to move in packs, or homogeneous clusters, according to the function they perform in the organization. To put this another way, staff members are not often found in the structure as individuals reporting with operators or different staffers directly to line managers of market units they serve. In- stead, they tend in the first instance to report to managers of their own specialty—the accountant to a controller, the work-study analyst to the manager of industrial engineering, the scientist to the chief of the research laboratory, the chef to the manager of the plant cafeteria. This in large part reflects the need to encourage specialization in their knowledge and skills, as well as to balance their use efficiently across the whole organization. For example, the need for specialization as well as its high cost dictate that there be only one research laboratory in many organizations.

Sometimes, in fact, an individual analyst, such as an accountant, is placed within a market unit, ostensibly reporting to its line manager. But he is there to exercise control over the behavior of the line unit (and its manager), and whether de facto or de jure, his allegiance runs straight back to his specialized unit in the technostructure.

But at some point—for staff units if not for staff individuals—the question arises as to where they should be placed in the superstructure. Should they be dispersed in small units to the departments they are to serve—often market-based units—or should they be concentrated into larger ones at a central location to serve the entire organization? And how high up in the superstructure should they be placed; that is, to line manag- ers at what level should they report?

As for level, the decision depends on the staffers’ interactions. A unit of financial experts who work with the chief executive officer would natu- rally report to him, and one of work-study analysts might report to the manager at the plant level. As for concentration or dispersal, the decision reflects all the factors discussed above, especially the tradeoff between work-flow interdependencies (namely, the interactions with the users) and the need for specialization and economies of scale. For example, in the case of secretaries, the creation of a pool allows for specialization (one secretary can type manuscripts, another letters, and so on) and the better balancing of personnel, whereas individual assignment allows for a closer rapport with the user (I cannot imagine every member of a typing pool learning to read my handwriting!). Thus, in universities, where the professors’ needs are varied and the secretarial costs low relative to those of the professors, secretarial services are generally widely dispersed. In contrast, university swimming pools, which are expensive, are concentrated, and libraries may go either way, depending on the location and specific needs of the various users.

Referring back to Figure 3-6, we find staff units at all levels of the hierarchy, some concentrated at the top, others dispersed to the market divisions and functional departments. The corporate secretariat serves the whole organization and links closely with the top management; thus, it reports directly to the strategic apex. The other units are dispersed to serve more or less local needs. One level down, public relations is attached to each of the national general managers so that, for example, each subsidiary can combat political resistance at the national level. Planning is dispersed to the next level, the product divisions, because of their conglomerate nature; each must plan independently for its own distinct product lines. Other staff units, such as work study, are dispersed to the next, functional level, where they can serve their respective factories. (We also find our ubiquitous cafeteria here—one for each plant.) Finally, the maintenance department is dispersed down to the general-foreman level, to serve fabri- cating or assembly.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.