The firm recognizes three different pricing situations: normal, sales, and mark-down pricing. The first two situations occur at regularly planned times. The third is a contingent situation, produced by failure or anticipated failure with respect to organizational goals. In each pricing situation the basic procedure is the same, the application of a mark-up to a cost to determine an appropriate price (subject to some rounding to provide convenient prices).

The bulk of sales occur at prices set by either normal or sales pricing procedures. Mark-down pricing is one of the main strategies considered when search is stimulated. During the time period we observed, the demand was strong enough to permit fairly consistent achievement of the department’s pricing goal — an average realized mark-up in the neighborhood of 40 per cent. As a result, we did not observe actual situations in which the pressure to reduce prices stemming from inventory feedback conflicted with the pressure to maintain or raise mark-up stemming from over-all mark-up feedback.

1. Normal pricing

Normal pricing is used when new output is accepted by the department for sale. As we have already observed, the problem of pricing is simplified considerably by the practice of price lining. In effect, the retail price is determined first and then output that can be priced (with the appropriate mark-up) at that price is obtained. Since manufacturers are aware of the standard price lines, their products are also standardized at appropriate costs.

For each product group in the firm there is a normal mark-up. Like the seasonal advance order fraction, mark-up is probably subject to long-run learning. For example, it varies in a general way from product group to product group according to the apparent risks involved, the costs of promotion or handling, the extent of competition, and the price elasticity. However, in any short run the normal mark-up is remarkably stable. The statement is frequently made in the industry that mark- ups have remained the same for the last 40 or 50 years.

Standard items. In the department under study, normal mark-up is 40 per cent. By industry practice, standard costs (wholesale prices) ordinarily end in $.75. By firm policy, standard prices (retail prices) ordinarily end in $.95. Thus, all but two of the price levels are in accord with the following rule:

Divide each cost by 0.6 (1 – mark-up) and move the result to the nearest $.95. The results of this rule and the effective mark-ups are shown in Table 7.1.

Exclusive items. In some cases, the department obtains items that are not made available to competition. For such products and especially where quality is difficult to measure, the prices are set higher than the standard. The pricing rule is as follows:

When merchandise is received on an exclusive basis, calculate the standard price from the cost, then use the next highest price on the standard schedule.

Import items. Presumably because they are frequently exclusive items, because of somewhat greater risks associated with foreign suppliers, and because of the generally lower costs of items of foreign manufacture for equal quality, the department increases the mark-up for imported items. For the product class studied the standard accepted mark-up is 50 per cent greater than normal mark-up (which gives a target mark-up of 60 per cent). This leads to the following rule for pricing imports:

Divide the cost by 0.4 (i.e., 1 — mark-up) and move the result to the nearest standard price. If this necessitates a change of more than $.50, create a new price at the nearest appropriate ending (that is, $.95 or $.00).

2. Regular sale pricing

We can distinguish two situations in which normal pricing is not used; one is during the regular sales held by the firm a few times during the year, the other when the department concludes that a mark-down is needed to stimulate purchases or to reduce inventory levels. In this section we consider the first case. As in the case of normal pricing, sales pricing depends on a series of relatively simple rules. In almost all cases sales pricing is a direct function of either the normal price (i.e., there is a standard sales reduction in price) or the cost (i.e., there is a sales mark-up rule). Both the figures on reduction and the sales mark-up are conventional, subject perhaps to long-run learning but invariant during our observations. The general pricing rules for sales operate within a series of constraints that serve to enforce minor changes either to ensure consistency within the pricing (e.g., maintain price differentials between items, maintain price consistency across departments), or to provide attractive price endings (e.g., do not use standard price endings, if feasible use an “alliterative” price). General constraints. The department prices for sales within a set of five policy constraints. These constraints have not changed in recent years and are viewed by the organization as basic firm policy. They are subject to review rarely.

- If normal price falls at one of the following lines, the corresponding sale price will be used:

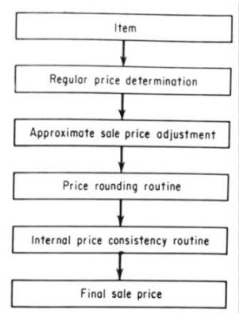

Figure 7.3 Major subroutines of sale pricing decision.

- For all other merchandise, there must be a reduction of at least 15 per cent on items retailing regularly for $3.00 or less and at least 16⅔ per cent on higher- priced items.

- All sales prices must end with 0 or 5.

- No sale retails are allowed to fall on price lines normal for the product group concerned

- Whenever there is a choice between an ending of 0.85 and 0.90, the latter ending will prevail.

Departmental decision rules. Subject to the general policy constraints, the department is allowed a relatively free hand. Since the policy constraints do not uniquely define sales pricing, it is necessary to determine the departmental decision rules. These rules are indicated in detail in the flow charts in Figs. 7.3 and 7.4.

3. Mark-down pricing

In our earlier discussions of organizational decision making, we suggested that a general model of pricing and output determination must distinguish between the ordinary procedures (that account for most of the decisions made) and the special search procedures that are triggered by special circumstances. We have already seen how such procedures enter into the determination of output in the present case. We turn now to search and “emergency” behavior on the price side. Price is the major adaptive device open to the department in its efforts to meet its mark-up goal, maintain sales, maintain inventory control, and in general meet the demands of other parts of the organization. We have already indicated how an increase in mark- up (e.g., on imports and special items) is used by the department. We turn now to mark-downs.

The department has two decisions to make on mark-downs: when, and how much? In a general sense, the answer to the first question — the question of timing — is simple. The organization reduces price when feedback indicates an unsatisfactory sales or inventory position. The indicators include the inventory records, sales records, physical inventory, reports on competitive prices, and the open-to-buy report. Mark-downs because of product properties (e.g., defects) are of secondary importance. With respect to the amount of mark-down, the organization has a set of standard rules.

Figure 7.4 Flow chart for sale pricing decision.

These have developed over time in such a way that their rationale can only be inferred in most cases, but a general characteristic of the rules is the avoidance of pricing below cost except as a last resort.Timing of mark-downs. Occasions for mark- downs are primarily determined by feedback on sales performance. There are three general overstock situations that account for the majority of the mark-downs:

- Normal remnants. These are the odd sizes, less popular colors, and less favored styles remaining from the total assortment of an item that sold satisfactorily during the season.

- Overstocked merchandise.This category includes items that have experienced a satisfactory sales rate but about which the buyer was overly optimistic in his orders. As a result, the season ends with a significant inventory that is well balanced and includes many acceptable items.

- Unaccepted merchandise. This category represents merchandise that has had unsatisfactory sales. The sales personnel try to determine during the season whether the lack of acceptance is due to overpricing or to poor style, color, and so forth. The distinction is usually made by determining whether the item has been ignored. If it has, the latter causes are usually inferred. It the item gets attention but low sales, the inference is that the price is wrong.

In addition, there are a number of quantitatively less important reasons for considering mark-downs. For example, the firm will meet competition on price (if a check indicates the competitor’s price is not a mistake). If a customer seeks an adjustment because of defects in the merchandise, a mark-down will be taken. If special sale merchandise is depleted during a sale, regular merchandise will be reduced in price to fill the demand. If wholesale cost is reduced during the season, price will be reduced correspondingly. If nonreturnable merchandise is substandard on arrival, it will be reduced.

Most of the merchandise that becomes excess (especially for the reasons outlined above) will be mentally transferred to an “availability pool.” When a specific opportunity arises or when certain conditions develop that necessitate a mark-down, items are drawn out of this pool and marked down for the occasion involved. Store- wide clearances are scheduled by the merchandise manager on nonrecurring dates throughout the year (except during the pre-Fourth-of-July period and the after- Christmas period) to provide all departments with an opportunity to clear out their excess stocks.

However, there may be times during the year when the department cannot wait for the next scheduled clearance for reasons of limited space or limited funds. If, for example, the department is expecting a shipment of new merchandise at a time when display and storage facilities are inade-quate to accommodate the new shipment, it is necessary to reduce inventory by means of mark-downs.

The department may take mark-downs when its open-to-buy is unsatisfactory. (Whenever the open-to-buy falls to the -$15,000 level, it would be judged to be in unsatisfactory condition.) The department will not necessarily take mark-downs as the principal means of rectifying this state of affairs per se but will attempt instead to cancel merchandise on order or to charge back merchandise already received. These steps will not be taken if the department expects relief from an increased sales rate within the immediate future or if the present average mark-up is low. However, if the department has an urgent need to purchase additional merchandise and the open-to- buy at the time is in the red to the extent that the division merchandise manager will not approve any additional orders, the department will then take mark-downs for the amount necessary to permit the desired purchase to take place.

Amount of mark-down. The complete model for predicting actual mark-down prices is given in Fig. 7.5. The general rule for first mark-downs is to reduce the retail price by 1/3 and carry the result down to the nearest mark-down ending (i.e., to the nearest $.85). There are some exceptions. Where the ending constraint forces too great a deviation from the 1/3 rule (e.g., where the regular price is $5.00 or less), ad hoc procedures are occasionally adopted. On higher-priced items, a 40 per cent markdown is taken. On a few items manufacturers maintain price control. Occasionally, items represent a closeout of a manufacturer’s line and a greater mark- down is taken.

Although the department did not seem to follow any specific explicit rule with second or greater mark-downs, the higher the first mark-down value the greater tended to be the reduction to the succeeding mark-down price. In fact, this relationship seemed to follow the top half of the parabolic curve

![]()

where Y = succeeding mark-down price X = initial mark-down price

Accordingly, the following empirically derived rule seems to work well with second or higher mark-downs:

Insert the value of the initial mark-down price in the parabolic formula and carry the result down to the nearest $.85 ($.90).

As a description of process, this rule is obviously deficient. However, in view of the limited number of cases involved and the inability of the department to articulate the rules, we have used this rough surrogate.

Figure 7.5 Flow chart for ![]() mark-down routine.

mark-down routine.

Source: Skyttner Lars (2006), General Systems Theory: Problems, Perspectives, Practice, Wspc, 2nd Edition.