Theory of divided legislative power.

Government and legislation are best divided between a federal state and its constituent states, departments, or areas.

Such division of power is normally regulated by a written constitution, with a supreme or constitutional court to adjudicate in disputes between the overall federal states and the separate component states.

Source:

K Sawer, Modern Federalism (London, 1969)

The terms “federalism” and “confederalism” both have a root in the Latin word foedus, meaning “treaty, pact or covenant”. Their common meaning until the late eighteenth century was a simple league or inter-governmental relationship among sovereign states based upon a treaty. They were therefore initially synonyms. It was in this sense that James Madison in Federalist 39 had referred to the new US Constitution as “neither a national nor a federal Constitution, but a composition of both” (i.e. as constituting neither a single large unitary state nor a league/confederation among several small states, but a hybrid of the two).[7] In the course of the nineteenth century the meaning of federalism would come to shift, strengthening to refer uniquely to the novel compound political form established at Philadelphia, while the meaning of confederalism would remain at a league of states.[8] Thus, this article relates to the modern usage of the word “federalism”.

Modern federalism is a system based upon democratic rules and institutions in which the power to govern is shared between national and provincial/state governments. The term federalist describes several political beliefs around the world depending on context. Since the term federalization also describes distinctive political processes, its use as well depends on the context.[9]

In political theory, two main types of federalization are recognized:

- integrative,[10] or aggregative federalization,[11] designating various processes like: integration of non-federated political subjects by creating a new federation, accession of non-federated subjects into an existing federation, or transformation of a confederation into a federation

- devolutive,[10] or dis-aggregative federalization:[12] transformation of a unitary state into a federation

Federalism is sometimes viewed in the context of international negotiation as “the best system for integrating diverse nations, ethnic groups, or combatant parties, all of whom may have cause to fear control by an overly powerful center.”[13] However, in some countries, those skeptical of federal prescriptions believe that increased regional autonomy is likely to lead to secession or dissolution of the nation.[13] In Syria, federalization proposals have failed in part because “Syrians fear that these borders could turn out to be the same as the ones that the fighting parties have currently carved out.”[13]

Federations such as Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia collapsed as soon as it was possible to put the model to the test.[14]

Early origins

An early historical example of federalism is the Achaean League in Hellenistic Greece. Unlike the Greek city states of Classical Greece, each of which insisted on keeping its complete independence, changing conditions in the Hellenistic period drove many city states to band together even at the cost of losing part of their sovereignty – similar to the process leading to the formation of later federations.

Explanations for adoption

According to Daniel Ziblatt’s Structuring the State, there are four competing theoretical explanations in the academic literature for the adoption of federal systems:

- Ideational theories, which hold that a greater degree of ideological commitment to decentralist ideas in society makes federalism more likely to be adopted.

- Cultural-historical theories, which hold that federal institutions are more likely to be adopted in societies with culturally or ethnically fragmented populations.

- “Social contract” theories, which hold that federalism emerges as a bargain between a center and a periphery where the center is not powerful enough to dominate the periphery and the periphery is not powerful enough to secede from the center.

- “Infrastructural power” theories, which hold that federalism is likely to emerge when the subunits of a potential federation already have highly developed infrastructures (e.g. they are already constitutional, parliamentary, and administratively modernized states).[15]

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant was an advocate of federalism, noting that “the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils” so long as they possess an appropriate constitution which pits opposing factions against each other with a system of checks and balances. In particular individual states required a federation as a safeguard against the possibility of war.[16]

Examples

Europe vs. the United States

In Europe, “Federalist” is sometimes used to describe those who favor a common federal government, with distributed power at regional, national and supranational levels. Most European federalists want this development to continue within the European Union.[17] European federalism originated in post-war Europe; one of the more important initiatives was Winston Churchill’s speech in Zürich in 1946.[18]

In the United States, federalism originally referred to belief in a stronger central government. When the U.S. Constitution was being drafted, the Federalist Party supported a stronger central government, while “Anti-Federalists” wanted a weaker central government. This is very different from the modern usage of “federalism” in Europe and the United States. The distinction stems from the fact that “federalism” is situated in the middle of the political spectrum between a confederacy and a unitary state. The U.S. Constitution was written as a reaction to the Articles of Confederation, under which the United States was a loose confederation with a weak central government.

In contrast, Europe has a greater history of unitary states than North America, thus European “federalism” argues for a weaker central government, relative to a unitary state. The modern American usage of the word is much closer to the European sense. As the power of the Federal government has increased, some people[who?] have perceived a much more unitary state than they believe the Founding Fathers intended. Most people politically advocating “federalism” in the United States argue in favor of limiting the powers of the federal government, especially the judiciary (see Federalist Society, New Federalism).

In Canada, federalism typically implies opposition to sovereigntist movements (most commonly Quebec separatism).

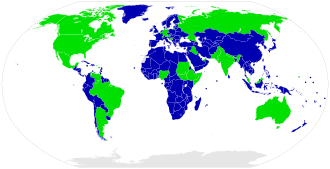

The governments of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, India, and Mexico, among others, are also organized along federalist principles.

Federalism may encompass as few as two or three internal divisions, as is the case in Belgium or Bosnia and Herzegovina. In general, two extremes of federalism can be distinguished: at one extreme, the strong federal state is almost completely unitary, with few powers reserved for local governments; while at the other extreme, the national government may be a federal state in name only, being a confederation in actuality.

In 1999, the Government of Canada established the Forum of Federations as an international network for exchange of best practices among federal and federalizing countries. Headquartered in Ottawa, the Forum of Federations partner governments include Australia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan and Switzerland.

Anarchism

Anarchists are against the state, but they are not against political organization or “governance”, so long as it is self-governance utilizing direct democracy. The mode of political organization preferred by anarchists, in general, is federalism or confederalism. However, the anarchist definition of federalism tends to differ from the definition of federalism assumed by pro-state political scientists. The following is a brief description of federalism from section I.5 of An Anarchist FAQ:

- “The social and political structure of anarchy is similar to that of the economic structure, i.e., it is based on a voluntary federation of decentralized, directly democratic policy-making bodies. These are the neighborhood and community assemblies and their confederations. In these grassroots political units, the concept of “self-management” becomes that of “self-government”, a form of municipal organisation in which people take back control of their living places from the bureaucratic state and the capitalist class whose interests it serves.

- […]

- The key to that change, from the anarchist standpoint, is the creation of a network of participatory communities based on self-government through direct, face-to-face democracy in grassroots neighborhood and community assemblies [meetings for discussion, debate, and decision making].

- […]

- Since not all issues are local, the neighborhood and community assemblies will also elect mandated and re-callable delegates to the larger-scale units of self-government in order to address issues affecting larger areas, such as urban districts, the city or town as a whole, the county, the bio-region, and ultimately the entire planet. Thus the assemblies will confederate at several levels in order to develop and co-ordinate common policies to deal with common problems.

- […]

- This need for co-operation does not imply a centralized body. To exercise your autonomy by joining self-managing organisations and, therefore, agreeing to abide by the decisions you help make is not a denial of that autonomy (unlike joining a hierarchical structure, where you forsake autonomy within the organisation). In a centralized system, we must stress, power rests at the top and the role of those below is simply to obey (it matters not if those with the power are elected or not, the principle is the same). In a federal system, power is not delegated into the hands of a few (obviously a “federal” government or state is a centralized system). Decisions in a federal system are made at the base of the organisation and flow upwards so ensuring that power remains decentralized in the hands of all. Working together to solve common problems and organize common efforts to reach common goals is not centralization and those who confuse the two make a serious error – they fail to understand the different relations of authority each generates and confuse obedience with co-operation.

Very interesting info !Perfect just what I was looking for! “To see what is right, and not to do it, is want of courage or of principle.” by Lisa Alther.

I have read so many articles or reviews on the topic of the blogger lovers except this paragraph is truly a nice post, keep it up.|

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again very soon!