Recall that structure involves two fundamental requirements—the division of labor into distinct tasks, and the achievement of coordination among these tasks. In Ms. Raku’s Ceramico, the division of labor—wedging, form-ing, tooling, glazing, firing—was dictated largely by the job to be done and the technical system available to do it. Coordination, however, proved to be a more complicated affair, involving various means. These can be re- ferred to as coordinating mechanisms, although it should be noted that they are as much concerned with control and communication as with coordi- nation.

Five coordinating mechanisms seem to explain the fundamental ways in which organization coordinate their work: mutual adjustment, direct supervision, standardization of work processes, standardization of work outputs, and standardization of worker skills. These should be considered the most basic elements of structure, the glue that holds or- ganizations together. Let us look at each of them briefly.

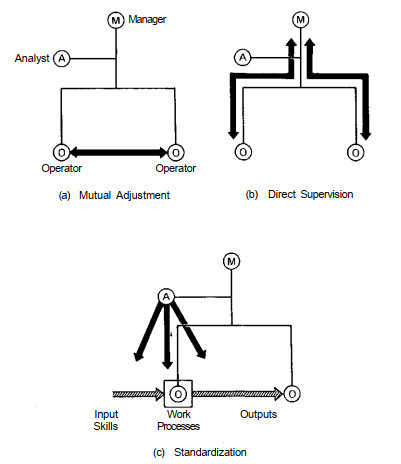

- Mutual adjustment achieves the coordination of work by the simple process of informal communication. Under mutual adjustment, control of the work rests in the hands of the doers, as shown in Figure l-l(a). Be- cause it is such a simple coordinating mechanism, mutual adjustment is naturally used in the very simplest of organizations—for example, by two people in a canoe or a few in a pottery studio. Paradoxically, it is also used in the most complicated. Consider the organization charged with putting a man on the moon for the first time. Such an activity requires an incredibly elaborate division of labor, with thousands of specialists doing all kinds of specific jobs. But at the outset, no one can be sure exactly what needs to be That knowledge develops as the work unfolds. So in the final analy- sis, despite the use of other coordinating mechanisms, the success of the undertaking depends primarily on the ability of the specialists to adapt to each other along their uncharted route, not altogether unlike the two peo- ple in the canoe.

- As an organization outgrows its simplest state—more than five or six people at work in a pottery studio, fifteen people paddling a war ca- noe—it tends to turn to a second coordinating (Direct supervi- sion achieves coordination by having one person take responsibility for” the work of others, issuing instructions to them and monitoring their actions, as indicated in Figure l-l(b). In effect, one brain coordinates sev- eral hands, as in the case of the supervisor of the pottery studio or the caller of the stroke in the war canoe. Consider the structure of an American football team. Here the division of labor is quite sharp: eleven players are distinguished by the work they do, its location on the field, and even its physical requirements. The slim halfback stands behind the line of scrim- mage and carries the ball; the squat tackle stands on the line and blocks. Mutual adjustments do not suffice to coordinate their work, so a field leader, called the quarterback, is named, and he coordinates their work by calling the plays.

Figure 1-1. The five coordinating mechanisms

Work can also be coordinated without mutual adjustment or direct supervision. It can be standardized. Coordination is achieved on the draw- ing board, so to speak, before the work is undertaken. The workers on the automobile assembly line and the surgeons in the hospital operating room need not worry about coordinating with their colleagues under ordinary circumstances—they know exactly what to expect of them and proceed accordingly. Figure l-l(c) shows three basic ways to achieve standardiza- tion in organizations. The work processes themselves, the outputs of the work, or the inputs to the work—the skills (and knowledge) of the people who do the work—can be designed to meet predetermined standards.

- Work processes are standardized when the contents of the work are specified, or programmed. An example that comes to mind involves the assembly instructions provided with a child’s Here, the manufacturer in effect standardizes the work process of the parent. (“Take the two-inch round-head Phillips screw and insert it into hole BX, attaching this to part XB with the lock washer and hexagonal nut, at the same time hold- ing “) Standardization can be carried to great lengths in organizations, as in the four assembly lines in Ceramics Limited, or the pie filler I once observed in a bakery who dipped a ladle into a vat of pie filling literally thousands of times every day—cherry, blueberry, or apple, it made no difference to him—and emptied the contents into a pie crust that came around on a turntable. Coordination of his work was accomplished by whoever designed that turntable. Of course, other work standards leave more room to maneuver: the purchasing agent may be required to get at least three bids on all orders over $10,000 but is otherwise left free to do his work as he sees fit.

- Outputs are standardized when the results of the work—for exam- ple, the dimensions of the product or the performance—are specified. Taxi drivers are not told how to drive or what route to take; they are merely informed where to deliver their The wedger is not told how to prepare the clay, only to do so in four-pound lumps; the thrower on the wheel knows that those lumps will produce pots of a certain size (his own output standard). With outputs standardized, the coordination among tasks is predetermined, as in the book bindery that knows that the pages it receives from one place will fit perfectly into the covers it receives from another. Similarly, all the chiefs of the Ceramico divisions coordinated with headquarters in terms of performance standards. They were expected to produce certain profit and growth levels every quarter; how they did this was their own business.

- Sometimes neither the work nor its outputs can be standardized, yet coordination by standardization may still be required. The solution—used by Ms. Raku to hire assistants in the pottery studio—is to standardize the worker who comes to the work, if not the work itself or its outputs. Skills (and knowledge) are standardized when the kind of training required to perform the work is specified. Commonly, the worker is trained even before joining the organization. Ms. Raku hired potters from school, just as hospitals engage doctors. These institutions build right into the workers- to-be the work programs, as well as the bases of coordination. On the job, the workers appear to be acting autonomously, just as the good actor on the stage seems to be speaking extemporaneously. But in fact both have learned their lines well. So standardization of skills achieves indirectly what standardization of work processes or of work outputs does directly: it controls and coordinates the work. When an anesthesiologist and a sur- geon meet in the operating room to remove an appendix, they need hardly communicate; by virtue of their training, they know exactly what to expect of each other. Their standardized skills take care of most of the coordination.

These are our five coordinating mechanisms, and they seem to fall into a rough order. As organizational work becomes more complicated, the favored means of coordination seems to shift from mutual adjustment to direct supervision to standardization, preferably of work processes, otherwise of outputs, or else of skills, finally reverting back to mutual adjustment.

A person working alone has no great need for any of the mecha- nisms—coordination takes place simply, in one brain. Add a second per- son, however, and the situation changes significantly. Now coordination must be achieved across brains. Generally, people working side by side in small groups adapt to each other informally; mutual adjustment becomes the favored means of coordination. As the group gets larger, however, it becomes less able to coordinate informally. A need for leadership arises. Control of the work of the group passes to a single individual—in effect, back to a single brain that now regulates others; direct supervision be- comes the favored coordinating mechanism.

As the work becomes more involved, another major transition tends to occur—toward standardization.’When the tasks are simple and routine, the organization is tempted to rely on the standardization of the work processes themselves. But more complex work may preclude this, forcing the organization to turn to standardization of the outputs—specifying the results of the work but leaving the choice of process to the worker. In very complex work, on the other hand, the outputs often cannot be standard- ized either, and so the organization must settle for standardizing the skills of the worker, if possible. Should, however, the divided tasks of the orga- nization prove impossible to standardize, it may be forced to return full cycle, to favor the simplest yet most adaptable coordinating mechanism— mutual adjustment. As noted earlier, sophisticated problem solvers facing extremely complicated situations must communicate informally if they are to accomplish their work.

Our discussion up to this point implies that under specific conditions, an organization will favor one coordinating mechanism over the others. It also suggests that the five are somewhat substitutable; the organization can replace one with another. These suggestions should not, however, be taken to mean that any organization can rely on a single coordinating mechanism. Most, in fact, mix all five. At the very least, a certain amount of direct supervision and mutual adjustment is always required, no matter what the reliance on standardization. Contemporary organizations simply cannot exist without leadership and informal communication, even if only to override the rigidities of standardization. In the most automated (that is, fully standardized) factory, machines break down, employees fail to show up for work, schedules must be changed at the last minute. Supervisors must intervene, and workers must be free to deal with unexpected problems.

This favoring and mixing of the coordinating mechanisms is also reflected in the literature of management across this century. The early literature focused on formal structure, the documented, official relationship among members of the organization. Two schools of thought dominated the literature until the 1950s, one preoccupied with direct supervision, the other with standardization.

The “principles of management” school, fathered by Henri Fayol, who first recorded his ideas in 1916, and popularized in the English-speak- ing world by Luther Gulick and Lyndall Urwick, was concerned primarily with formal authority—in effect, with the role of direct supervision in the organization. These writers popularized such terms as unity of command (the notion that a “subordinate” should have only a single “superior”), scalar chain (the direct line of this command from chief executive through successive superiors and subordinates to the workers), and span of control (the number of subordinates reporting to a single superior).

The second school really includes two groups that, from our point of view, promoted the same issue—the standardization of work throughout the organization. Both groups were established at the turn of the century by outstanding researchers, one on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. In America, Frederick Taylor led the “Scientific Management” movement, whose main preoccupation was the programming of the contents of oper- ating work—that of pig-iron handlers, coal shovelers, and the like. In Germany, Max Weber wrote of machinelike, or “bureaucratic” structures where activities were formalized by rules, job descriptions, and training.

And so for about half this century, organization structure meant a set of official, standardized work relationships built around a tight system of formal authority.

With the publication in 1939 of Roethlisberger and Dickson’s in- terpretation of a series of experiments carried out on workers at the West- ern Electric Hawthorne plant came the realization that other things were going on in organizational structures. Specifically, their observations about the presence of informal structure—unofficial relationships within the work group—constituted the simple realization that mutual adjustment serves as an important coordinating mechanism in all organizations. This led to the establishment of a third school of thought in the 1950s and 1960s, originally called “human relations,” whose proponents sought to demon- strate by empirical research that reliance on formal structure—specifically, on the mechanisms of direct supervision and standardization—was at best misguided, at worst dangerous to the psychological health of the worker. More recent research has shifted away from these two extreme posi- tions. In the last decade, there has been a tendency to look at structure more comprehensively; to study, for example, the relationships between the formal and informal, between direct supervision and standardization on the one hand and mutual adjustment on the other. These studies have demonstrated that formal and informal structures are intertwined and often indistinguishable. Some have shown, for example, how direct su- pervision and standardization have sometimes been used as informal de- vices to gain power, and conversely, how devices to enhance mutual ad- justment have been designed into the formal structure. They have also conveyed the important message that formal structure often reflects official recognition of naturally occurring behavior patterns. Formal structures evolve in organizations much as roads do in forests—along well-trodden paths.

Source: Mintzberg Henry (1992), Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations, Pearson; 1st edition.