The three firms observed are all well-established, successful organizations: a large, heavy manufacturing concern, a medium-sized construction firm, and a medium- large manufacturing and retailing concern. Each of the firms gave the research group full access to files and to the activities of the organization. The decisions and the studies were made during 1953-1956. Three basic techniques of observation were used: (1) detailed analysis of memoranda, letters, and other written file material, (2) intensive interviews with participants in the decisions, and (3) direct observation of the decision process. The first two techniques were used in every case. All pertinent documents (all those relating in any way to the decision being studied) in the companies’ files were examined. All participating members of the organization were interviewed at least once; key members were interviewed repeatedly. In two cases (the second and fourth below), an observer from the research team was present virtually full-time in the organization during the time the decision was being made. He was attached directly to a staff member in the organization and attended staff meetings. In the fourth case, the observer was permitted, in addition, to tape record important meetings.

The data on the decisions are, therefore, as complete as the limits of memory (both organizational and personal), interview technique, and observer ability permitted.

Since those limits can be surprisingly restrictive, some questions of detail could not be answered. Nevertheless, the case studies described below are based on substantial information, direct and indirect. For purposes of presentation they have been condensed considerably, and emphasis has been placed on one aspect of the situation -the role of expectations. We are well aware of the dangers in such an abstraction, and we scarcely hope that four case studies, however detailed, will allay the skepticism of critical readers. The justification lies in our belief that the key propositions we want to make are conspicuous in the data and in our hope that the data will provide a start for empirical research in an area of extensive ad hoc theory.

1. Decision 1: a problem in accelerated renovation of old equipment

The first decision problem we shall analyze arose in a branch plant of a heavy manufacturing corporation employing several thousand workers and divided into semiautonomous operating divisions — seven major and several smaller divisions. Auxiliary service departments (such as safety) reported to the plant manager and his assistants, but most such departments had liaison personnel assigned to the operating division.

An important goal of management was to achieve a better safety record than other plants in the corporation and in the industry. Particular stress was placed on eliminating fatal accidents and on achieving annual reductions in the frequency of lost-time injuries. Making the plant as safe a place to work as possible was more than a plant goal; it was a personal objective of most members of top management in the firm.

All the large divisions and most of the small ones made extensive use of overhead cranes, and the movement of most cranes was governed by an old type of controller. Most cranemen and supervisors preferred magnetic controllers, a newer type that had been installed on many cranes in the plant. Because magnetic controllers operated on low-voltage control circuits, there was less danger of severe shock or of “flash” — visible arcing of current across contact points — than with the old type, which operated on full-line voltage. Magnetic controllers also allowed operators to direct crane movements more precisely — there was less danger of “drift” or unanticipated movements. Since they used less cab space than some older controllers, they offered the craneman better visibility and more work space. They were also supposedly cooler and less fatiguing to operate, as well as easier to maintain.

The actual safety benefits that would accrue from the replacement of old-type controllers with magnetic controllers were hard to estimate. Burns, shocks, and eye injuries resulted from “flash” in the older controller circuits, but they were infrequent and were not often disabling. Injuries caused by movements of cranes were more frequently attributable to human error by cranemen or ground crews than to mechanical failure of the controllers or to drift.

Changeovers to magnetic controllers were being made only as the older controllers wore out, until a fatal accident in the plant triggered recommendations for an accelerated replacement program. A worker was killed when the unexpected movement of a crane load pinned him against a wall. Investigation by top management and by the safety department led to recommendations for a general review of the problems of crane safety.

The plant manager appointed a special committee to recommend steps that could be taken to improve a craneman’s view of his working areas and to give him better control over crane movements. The committee consisted of the director of safety, the superintendents of two operating divisions, and a man from the plant engineering department.

At the initial investigation of the accident, the craneman had been asked the type of controller with which the crane was equipped, but no links had been suggested between type of controller and the accident. Blame was assigned to the victim for standing in an unsafe position, to the craneman for moving a lift when his view was obscured, and to management for improper stacking of materials on the floor.

The special crane-safety committee did not mention magnetic controllers in its first report of recommendations for the division where the accident had occured. Not until their seventh meeting several weeks after the accident, while investigating conditions in a second division, did the committee discuss a suggestion for accelerated changeover of magnetic controllers. The change would “save space in the crane cab” and provide better control levers, but the committee feared initially that “the cost would be excessive.”

Apparently the committee changed its evaluation of the costs of the change, although minutes of the meetings do not report any further discussion. In its final report to the plant manager, the committee recommended as one of several changes that the controllers then in use “be replaced by magnetic controllers as quickly as feasible.” The plant manager circulated the entire list of recommendations without change to the division superintendents and asked that they all be adopted and implemented promptly.

After the order for implementation, specific questions of cost were raised and searches for information were initiated. Most division superintendents individually made quick estimates of the minimum cash outlays required for purchase and installation of the new controllers and checked with the plant manager to see if these expenditures would be approved. Their estimates ranged from $27,000 to $50,000 per division and were described by the safety director as “an absolute minimum” since they did not cover all expected costs of installation.

To supplement the divisional estimates and to fit the accelerated replacement program into operating budgets, the plant manager asked the chief engineer to make a plant-wide survey of requirements and installation costs. Four months after the accident the chief engineer asked the special crane-safety committee to draw up detailed plans for the replacement program and suggested that the program be included in the following year’s budget. He wrote, “It may be an expenditure between $150,000 and $200,000.”

Seven months later, in another memorandum to division superintendents, the chief engineer was still asking for an itemized list of cranes that required the new controllers and of the number of replacements each such crane would need. At this time he described the program as a five-year job with budgeted expenditures of $100,000 a year.

The chief engineer was not the only one to explore the costs and benefits of the program. In the meantime one of the division superintendents had announced the program to a plant-wide conference of management personnel. He said that the installation of magnetic controllers would “virtually eliminate” injuries to cranemen from flashes and burns. Several other division superintendents prepared a memorandum summarizing their objections to the old-type controllers. The chief industrial engineer reported to management that, for the new magnetic controllers, “any increased costs in operation will be negligible.” He mentioned the old-type controllers as a “cause” of the fatality that had initiated the program. 6

Early in the second year of the program the plant manager asked the superintendent of maintenance to coordinate the replacement program over the next several years. By the ninetieth week after the accident, the superintendent of maintenance had developed a revised plan for replacements. The estimated number of replacements had been decreased from 344 to 250, the estimated total cost increased from

$500,000 to $600,000, and the estimated time for completion of the program increased from five to six or seven years. He reported costs in terms of the program’s encroachment on men and facilities needed for other projects to which the maintenance division was committed. This was the first time in the written memoranda on the program that an estimate of available manpower to install the controllers was cited as a limit to the completion of the program.

Initially, then, the program for accelerated replacement of controllers had been judged expensive but feasible. The original recommendation for the program had been promulgated along with a number of other suggestions for increasing crane safety that could be implemented less expensively in the short run.

The first eighteen months after the program was approved by the plant manager were used to explore the scope of the decision and to plan for its implementation. Specific estimates of cost quadrupled in that time (rising from $150,000 to over

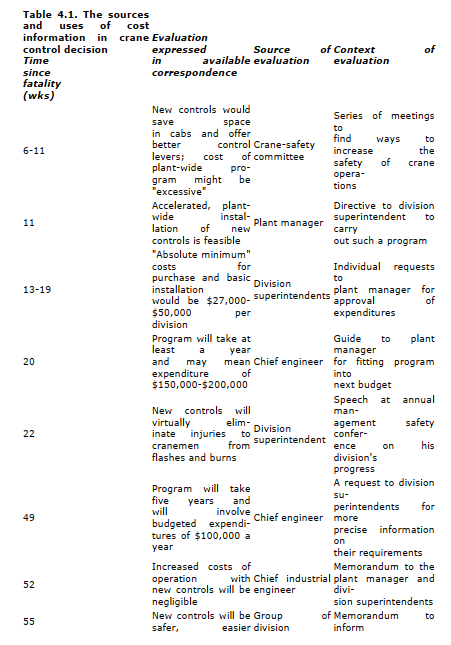

$600,000), and the estimated time for completion changed from about two years to seven or more. Apparently the firm’s commitment to an accelerated replacement program was made before the cost of new installations and the impact of the project on other commitments for maintenance and expansion were fully known. The development of cost information is summarized in Table 4.1.

In the end the commitment proved vulnerable — not to revised estimates of cost but to short-run declines in available resources. At the end of two years two divisions stopped work on the program because a decline in operations had reduced their funds. One year later almost all divisions had reverted, for similar reasons, to the policy they were following before the accident; they were installing magnetic controllers only as the older control systems wore out.Three major features of this decision process are especially interesting from the point of view of the place of expectations in a theory of business decision making:

- It is clear that search behavior by the firm was apparently initiated by an exogenous event, was severely constrained, and was distinguished by “local” rather than “general” scanning procedures.

- The noncomparability of cost expectations and expected returns led to estimates that were vague or easily changed and made the decision exceptionally susceptible to the factors of attention focus and available organizational slack.

- The firm considered resources as fixed and imposed feasibility, rather than optimality, tests on the proposed expenditure.

The search behavior is difficult to interpret. The apparent sequence is quite simple: accident, concern for safety, and focus (among other foci) on magnetic controllers. As a view of top management, such a sequence seems to be reasonably accurate. Underlying this sequence, however, are a number of factors that make too simple a theory of organizational search unwarranted. Most conspicuous is the fact that the connection between the stimulus (fatal accident) and the organizational reaction (new controllers) is remote. There is no evidence that the fatal accident depended on the type of controller used on the crane. At the same time, there is little doubt that the accident had made members of management give greater priority to any device that would improve crane safety and that the possibility of new controllers was well known to parts of the organization. Thus, organization search for safety alternatives at the level of top management can be viewed at lower levels as the promotion of favored projects under the impetus of a crisis. The alternative of magnetic controllers was discovered not so much because the organization at this time searched everywhere for solutions to a problem but because some parts of the organization were already (for whatever reason) predisposed toward the project and (1) thought of it as relevant and (2) were able to present it as relevant to the perceived problem in safety.

The decentralized characteristics of information gathering in this case are particularly striking in the pursuit of cost information. Cost information was not readily available, especially to the men who were charged with investigating crane safety. Each knew something about the costs of a single installation since some of these had already been made, but none of the four had the information needed for even a rough approximation of the over-all costs of an accelerated replacement program. Furthermore, as later searches showed, many people and much time would have been needed to gather such information. Even after the decision to make the plant-wide installations, when detailed cost and return data were sought, every new group brought in costs and advantages that other groups had not considered (see Table 4.1).

One of the reasons why detailed information on costs seems to play such an insignificant role in all but the final stages of the process is that at no time did the organization make a conscious calculation of costs and return in comparable figures. This feature of the decision is conspicuous in Table 4.1. Information about costs was not necessary to persuade members of management to order the installation of the controllers. All members of management apparently favored the new controls, and they were supported by noncompany technical literature. They had been putting the new controllers in as the old systems wore out. Statements made by the division superintendents indicated that they were placing strong positive emphasis on the safety advantages of the new controls. These gains were usually expressed in absolute rather than relative terms. None of the safety advantages and few of the operating advantages were ever formally expressed in dollar terms. There was consensus that the program would be beneficial and evidence that the benefits — whatever their size — would apply in several departments: safety, maintenance, and operating divisions.

Under these conditions it is not surprising that the early cost estimates were too optimistic (at least if we can assume later ones were more accurate). It is also not surprising to discover that variations in cost expectations had little impact on the basic decision until the focus on safety became less intense and free funds became scarce.

Measurable expectations entered in the decision only in the feasibility test. Do we have money for the controls? Initially, agreement by various groups in management that the step was a good one and an estimate that costs — although unknown — would not be unreasonable were apparently sufficient to carry the decision. For costs to be reasonable under the usual theory of investment, they must be better (relative to the gain) than other available alternatives. This was not, however, how the issue was formulated here. Rather, the question of “reasonableness” hinged on whether the expenditure could be made without appreciably affecting existing organizational arrangements adversely (e.g., profits, dividends, wages, output).

As long as estimated costs were modest and output high, the costs were reasonable. As the costs grew and business activity declined, accelerated installation of the magnetic controllers became less “reasonable.” This was obviously not because they became suboptimal whereas they had previously been optimal but simply because the supply of uncommitted resources (one form of organizational slack — see Chapter 3) had been substantially reduced. The later stages of the decision were dominated by the necessity for making specific provisions for the program in the plant budgets and for preparing tentative time schedules for installation. When, at this stage, there was not enough money for all of the approved projects, some comparisons of the relative merits were made. At that time the hierarchy of preferred projects seemed to reflect such considerations as the tangibility of their expected return, the importance of their major supporters, and the conspicuousness of the problem for which they were designed. It is, of course, possible that such a process also generates the optimum set of investments. We will note only that the explicit decisions made by two divisions to abandon the program corresponded in time with declines in their level of operations. When it became apparent that cash would not be available to meet more than the bare minimum of repair and maintenance commitments, the two divisions stopped work on the accelerated program completely and returned to preaccident policies.

2. Decision 2: a problem of new working quarters for a department with a doubtful future

The second decision was an attempt in a medium-sized construction firm to find new working and storage quarters for its home specialties department, which held a unique and somewhat insecure position in the firm. Its customers were not often shared by other departments. Like other departments of the firm but unlike most of its competitors, it used union labor; therefore, its labor costs were too high to enable it to bid successfully on many projects. Its labor costs and changes in style and technology in the construction industry were causing the department’s market to shrink, though it had shared with other departments in the growth from new construction activity during and after the Korean War. Top management expected its sales to decline, and its members outside the Home Specialties Department had negative feelings toward the department for two reasons:

- The head of the department was a senior man in the firm and his earnings under a profit-sharing contract were higher than the earnings of almost all other department heads.

- Other departments were also expanding, and some of these were anxious to take over space being used by Home Specialties.

The problem of making a decision about the long-run importance of Home Specialties operations and of providing plant facilities to accommodate expanded operations had been current for at least two years.

Management had long been aware of the need for some kind of action. However, there was no consensus on the critical problem nor on a satisfactory alternative. The president, who believed centralized operations were most efficient, initially viewed the problem as one of finding a way to expand facilities at (or in the immediate vicinity of) the current site. The head of the Home Specialties Department wanted to move the department to a new location, where it would not be in conflict with the operations of other units. Some members of general management thought that the department should be dropped from the firm in order to release working capital for units that had a brighter future. The president and the branch manager had talked of maintaining the department but limiting it to a size that fitted the existing site, reducing the share of profits going to departmental personnel, and forcing the head of the department to take a cut in earnings. Some years earlier, a few men had almost managed to force the department manager out of the firm.

The president’s show of interest when a local plot of land became available, coupled with continuing pressure from departmental management to investigate possible new sites, resulted in a decision to concentrate on the search for a new site. Study of the feasibility of moving the department may have seemed timely, too, because of the president’s independent decision to renegotiate profit-sharing contracts with departmental management. Since the department manager and his assistant wanted to move, a decision to support their search for a new location might have been regarded as an inducement to them to accept a cut in earnings. In addition, the move might make it easier to follow the cut in earnings with a later decision to curtail departmental operations or to ease the department out of the firm.

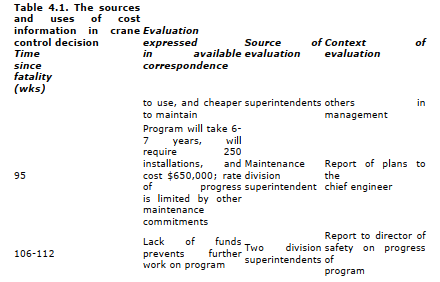

Requirements for the new site were set forth in a conference attended by the branch manager, the department head for Home Specialties, his assistant, and a specialist in estimating building alteration costs. The pressures on current facilities, at least, were not expected to increase greatly over the next year or two; in fact, the space requirements of Home Specialties were expected to decline. The Home Specialties facilities were probably not grossly unsuited to their operations; in defining the requirements for a new site, the head men in the department were merely trying, on most measures, to find something that would be equivalent to what they already had. The assistant head of the Home Specialties Department initiated most suggestions for site requirements; he worked from a memorandum he had prepared earlier. The final set of requirements was drafted by the branch manager after the meeting. The key specifications are set forth in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2. Selected site characteristics: aspirations vs. actions

The conference was notable for the absence of real debate about or explicit consideration of the relative importance of different kinds of requirements. The discussion was oriented towards ensuring that the new site would offer the same facilities as the old one at no greater cash outlay for rent, rather than toward determining what would be a “most efficient” site for the Home Specialties Department. The most intensive discussion with respect to several requirements centered on reaching an agreement as to what facilities the department had in its current location. The question of the flexibility of various requirements was hardly raised, although it was unreasonable to expect to find a site that corresponded to all of the committee’s specifications.

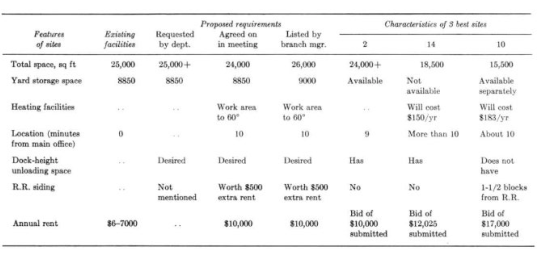

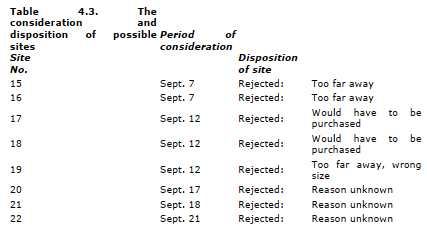

An intensive search for sites that lasted for four months followed the conference. The evaluation of each site about which information was received was a three-phase process. First, the branch manager or another member of the central management group looked at the initial information that was available from advertisements, phone calls, or cursory visits to the site to decide whether the site was worth further inspection. As Table 4.3 indicates, at least 18 sites were rejected at this stage because they failed to meet one of a small set of requirements. The most important considerations at this stage were (1) whether the site could be rented (the company did not want to purchase), (2) whether the site was located near the company’s existing facilities (something within 10 minutes’ driving distance was preferred), and (3) whether the site was approximately the right size (sites with 15,000 to 25,000 sq ft were preferred). One or more of these three factors underlay the rejection of 11 of the 18 sites in this early phase. (Of the remaining seven, one was rejected because of problems of access, one because of an unsatisfactory layout, and five for unknown reasons.)The second phase consisted of a more detailed evaluation of the site’s potentialities. Four sites were given detailed consideration. Members of the home specialties department staff estimated the expenditures required to make the necessary heating, lighting, and ventilating installations. One of the four sites was rejected after detailed inspection because the branch manager found it liable to frequent flood damage and because the company would have had to buy other leases on the property.There were, then, three sites that management thought worth preparing bids on. Looking at the major criteria of space, price, and nearness to existing facilities, we note in Table 4.3 that management relaxed its requirements as time went on. Site 2, the first one for which a bid was prepared, had an area about the same as the specifications required, but sites 10 and 14 were both smaller. Site 10 was at and site 14 was beyond the distance limits set by management. Management expected to acquire site 2 with a bid of $10,000-$15,000 for 24,000 sq ft of space; the bid on site 14 was $12,000 for 18,500 sq ft. On site 10, the third one for which a bid was prepared, management considered offering $17,000 for 15,500 sq ft of space (excluding yard space, which had to be obtained separately).The bids on sites 2 and 14 were turned down by the agents for the properties, but the bid on site 10 was never submitted. The president refused to approve the bid because he thought it offered too much money for too little space. The search for a new site for the home specialties department apparently ended with the president’s refusal to approve a bid for site 10.Why were other sites not considered? Among the reasons for ending the search, the following were perhaps most important:

- The branch manager and the others who had been most active in the search felt that they had explored most of the available possibilities. They had even resorted to driving around the neighborhood looking for “for rent” signs.

- The earnings contracts of the departmental managers had been renegotiated — most of them Use of the search for a new location as an inducement to counteract the negative effects of renegotiation was no longer of any importance, and, with renegotiation completed, one point of friction between Home Specialties and other departments had been eliminated.

Contrary to expectations, Home Specialties had continued to maintain a fairly high level of operations over the summer, while its most direct competitor for work space had suffered a decline in business.

The decision-making process in this case has some significant similarities to that connected with the purchase of automatic controllers. As before, search activity represented a response to some specific events rather than a form of continued planning. Second, detailed expectation data entered into the decision relatively late, after a conditional commitment to secure space had been made. Finally, most of the tests were primarily feasibility tests rather than checks on optimality.From the present point of view, perhaps the most interesting aspect of this study is the fact that the organization focused on the problem of outside space for the department. Although the decision was contingent (and was in fact never executed because bids were rejected), it represented a commitment to a course of action; yet the commitment was made not because it was shown to have the best return (in terms of organization goals) of a number of alternatives. Quite the contrary, the decision to find new quarters was made because a number of important parts of the organization, for apparently different reasons, viewed such a step as desirable. Had there been agreement, for example, between the Home Specialties Department and other departments about the probable long-run consequences of this step, one or the other of those groups would probably have opposed the move. Since this was an important aspect of the decision situation, some of the more important expectations were not discussed in open meetings. The role of ambiguity of expectations in securing agreement where there is a conflict of interests has previously been noted with respect to political and labor-management decision making. 8 There is some suggestion here that it is also important for the formation of business policy.Once the decision to secure additional space had been made, data on alternatives were organized around a set of more or less independent criteria. These criteria are interesting in two respects:

- They represent for the most part a simple statement of current facilities. The adequacy of some aspects of these facilities was discussed, but the general question of what would constitute an ideal site was not raised.

- With one or two exceptions (e.g., an attempt to place a rental value on the existence of a railroad siding), the specifications represented a check list. Sites that were unsatisfactory on one or more of the major criteria were rejected immediately. Only among the more or less “satisfactory” alternatives was there an attempt at comparison with a different dimension; and even at that point this comparison was somewhat halting and not always easily understood. Some of the sites rejected at an early stage might have been considered more thoroughly later, after management’s aspirations declined.

In one conspicuous feature the site purchase decision was different from the decision to purchase new automatic controllers. The search for alternative sites was much more exhaustive than the search for alternatives in the first case; the organization had no ready-made site alternative. Although it is conceivable that the organization did not discover all the alternatives that were within 10 minutes of the central office, it seems unlikely that they missed any that would have been suitable. To be sure, the use of the 10-minute criterion as a device for defining the range within which one would search made that criterion into an absolute one, in the sense in which the others (e.g., the size requirement) were not. However, the difference between the number of alternatives considered in this instance and in the crane case is substantial. Similarly, the specific cost estimates reflected in proposed bids for sites and the decisions on whether to make the bids, seem, in this case, to be more attempts to determine the intrinsic worth of the property to the organization and less a function of available resources than they were in the previous case.

3. Decision 3: selection of a consulting firm

The third decision is part of a larger decision regarding the installation of an electronic data-processing system. It relates specifically to the selection of a consulting firm. The company, a medium-large manufacturing concern, had made some preliminary investigation of the problem and decided that a consultant was necessary. At the beginning of the process of deciding which firm should be chosen, there was no clear program as to how many firms would be evaluated. A list of possible consultants was prepared, but a series of chance circumstances led to a meeting with Alpha, a relatively new consulting firm specializing in the design of electronic data-processing systems.

On February 21 consultants from Alpha and people from the company discussed the problem of improving business methods. By March 23 Alpha had submitted a step- by-step program that would survey and analyze the company’s operations and data- processing procedures. Alpha stated that the objective of this program would be (1) the estimation of savings that could be realized through the use of electronic equipment and (2) the specification of the price class and characteristics of equipment required. The fee expected for this work was stated as $180 per man-day (i.e., $3600 per month assuming one man works a 20-day month). The initial consulting task was to be limited to 100 man-days, and consequently the fee was limited to $18,000. Traveling expenses of some $4000 would also be charged.

The report was well received by company officials, who generally agreed that Alpha would be retained until the question of investigating other alternatives was raised. As will be obvious, this was a crucial point in the process, but it is not clear what prompted the suggestion for additional search effort. The suggestion was rather quickly accepted, and a list of about a dozen potential consultants, which had been prepared earlier by a staff member, was presented. The controller decided that only one more firm, Beta, should be asked to submit a proposal. Beta was more widely known, older, and larger than Alpha, although it did not specialize in electronic data- processing feasibility studies.

Following analysis of the problem, Beta submitted a contract proposal covering an investigation of the company’s problems. The stated objectives were two: (1) to reduce the costs of the accounting and clerical operation and (2) to improve the quality of information available for accounting and control. Beta stated in the contract proposal that employing electronic data-handling equipment was to be considered as a possible means of attaining these objectives. This contract outlined service charges that would not exceed $5000 a month. The initial study was to be completed and a report submitted three to four months after active work began.

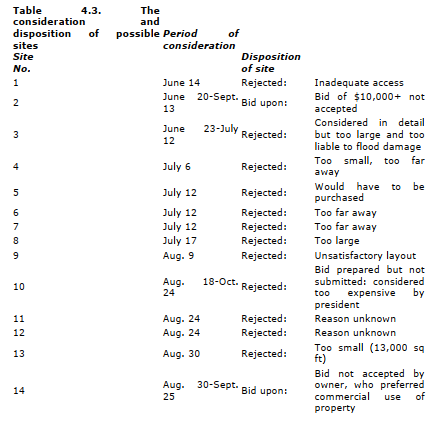

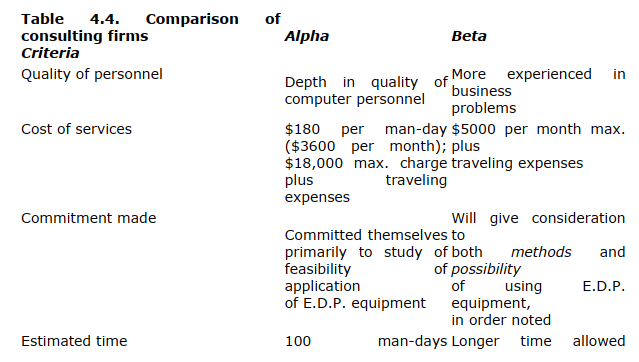

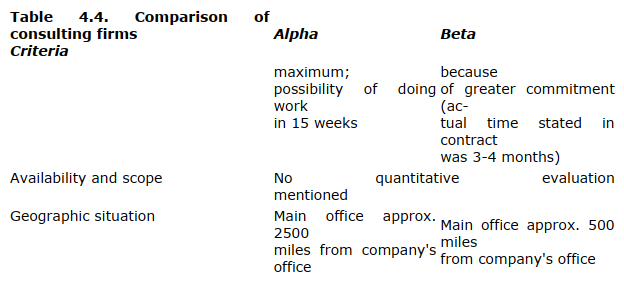

After Beta had submitted a report, it became necessary to choose between the two firms. At the request of the controller a staff member wrote a memorandum that listed the criteria on which the decision should be based and also evaluated the two firms on each of the criteria. The results of this memorandum are summarized in Table 4.4.

The staff member who wrote the memorandum believed that as far as quality of personnel, cost of services, and estimated time were concerned, the two firms were equal or could be made equal by negotiation. Regarding the other criteria — commitment made, availability and scope, and geographic situation — he felt Beta had an advantage. He was supported in this opinion by an academician who had previously served as a consultant to the company. Analysis of the memorandum seems to show, however, that the only advantage that can objectively be given to Beta is its geographic situation. Even here, aside from availability, it is difficult to see any advantage; the only possibility would be higher traveling expenses for Alpha, but presumably this would mean a reduction in some part of the fee. Again it should have been possible to negotiate on availability and scope, assuming that geographic proximity is divorced from availability. It is quite obvious that the commitment could have been negotiated because Alpha, as a new organization in the field, was open to suggestion with respect to the kind of commitments it should make.

On the cost side (ignoring possible negotiation) there was some ambiguity. The approximate monthly charges were $1400 less for Alpha than for Beta. The total charge for Beta to the company varied according to the length of time it would take. The estimated length of time for Beta was three to four months, which would mean a price between $15,000 and $20,000. Alpha, on the other hand, had a maximum price of $18,000. Exact price comparisons under the circumstances were difficult to make. Since Alpha gave a maximum total price whereas Beta used only a maximum monthly charge and no upper limit on the time, what advantage there was in the cost situation was probably in Alpha’s favor. However, the costs were close enough and the circumstances blurred enough so that relative cost was difficult to evaluate.

This fact was recognized by the staff members involved, who proposed that the decision be made on collateral grounds (e.g., geographic proximity, possible future uses). As noted above, the grounds specified seemed to favor Beta, and this preference of the staff was apparent almost from the moment that the decision to expand the search to Beta was made. That is, the staff members most closely involved seemed to view Alpha as a reasonable solution until the suggestion for further search was made. There is some suggestion that they interpreted the instruction to expand their search to include Beta and only Beta as a preference for Beta by their supervisors. The controller and assistant controller, on the other hand, felt that the final decision was based on the independent recommendations of their staff members and did not acknowledge the possibility that such an outcome was implicit in the decision not to accept Alpha until further investigation. The firm decided to hire Beta.

How did expectations with respect to cost and return enter the decision to hire Beta? First, the methods of search resulted in casual consideration of about a dozen possible firms, intensive consideration of two. Second, a comparison of the two firms finally considered was difficult. Expected costs and expected return were measured in a number of dimensions (e.g., fee, quality of personnel, convenience) that were not readily reduced to a single index. Third, given the difficulties of evaluation, there appears to have been substantial interaction between expectations and desires and between desires and perceptions of others’ desires.

As in the case of the search for a new site for the Home Specialties Department, there was some attempt here to be reasonably inclusive in searching for potential firms. Presumably, if that original scanning had uncovered a firm that was conspicuously more appropriate than all others, that fact would have been noted. Since there were no conspicuous alternatives, it is not surprising to discover that not many were evaluated in detail and that the factors affecting the choice of firms to consider in large part determined which firm would be selected. Alpha was considered because it was exceptionally visible to a key staff member when the organization needed a detailed proposal. Beta was conspicuous to the controller because it was well known in the business community and had apparently been considered as a potential consultant on other occasions.

In evaluating the proposal by Alpha and later in comparing it with the one made by Beta, the people involved in the decision seemed to have done two things: (1) They asked whether the charges were within the range of what it was reasonable for the organization to pay for the services offered. There does not appear to have been any significant problem on this score. (2) They asked which of the two proposals offered the better return on investment. As the description of the two firms indicates, this was by no means an easy job. The simple comparison of the two consulting firms in Table 4.4 has some interesting features. Perhaps most conspicuous is the fact that the conclusion to be drawn from the comparison is not at all clear. Reasonable men could quite easily disagree as to its implications. It was not that part of the return was in the form of intangibles; all of the factors explicitly considered were reasonably tangible. The problem was that they were not reducible to a single dimension (or at least were not reduced to one) and that neither firm was better on all dimensions.

The ambiguity in expectations that arose from the difficulty of making objective rankings of Alpha and Beta resulted in a decision process that seemed to be dominated in large part by nonexpectational factors. The final staff memorandum on the decision clearly recommended Beta. This recommendation was accepted by the controller. As he put it, “I asked the boys to set down the pros and cons. The decision was Beta. It was entirely their decision.”

The staff members involved, on the other hand, seemed to have felt that the decision to search further rather than hire Alpha immediately reflected some bias in favor of Beta on the part of top management, and this was probably reinforced by the fact that the controller specified that Beta and only Beta would be asked to make a proposal. Since the differences between the two firms were not particularly striking, it is not surprising that these plausible assumptions about the attitudes of others were consistent with subsequent perceptions of the alternatives and the final recommendation.

4. Decision 4: choosing a data- processing system

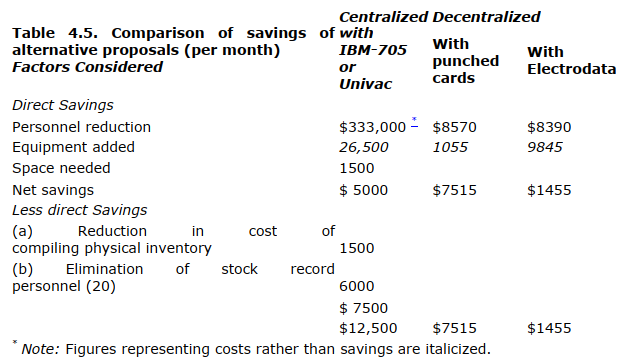

In November, six months after the original contract had been signed, Beta submitted a report which outlined some alternative proposals designed to improve the company’s accounting and merchandising procedures. Essentially three alternatives were discussed in the report: (1) a centralized electronic data-processing center employing an IBM 705 or a RemingtonRand Univac, (2) an improvement on the current procedures requiring the addition of some Electrodata equipment, and (3) an improvement on the current procedures requiring the use of punched-card electronic equipment instead of Electrodata equipment. These alternatives were differentiated on the basis of projected savings and improved management control. In each, savings were to accrue from the elimination of personnel. Management control was to be increased by additional reports, which would be more complete and more readily available.

The report shows a breakdown of the savings and reports provided under each system. A comparison of the savings for the three alternatives is shown in Table 4.5. The three alternatives have several significant differences. (1) The decentralized system with punched-card equipment has a larger projected direct savings than either of the other alternatives ($7515 savings for this system as opposed to $5000 savings, and $1455 additional cost for the other systems). (2) Only when the less direct savings of $7500 per month are added to the centralized system does this system become more attractive in price than the punched-card program. (3) The centralized system gives management six reports not provided by the other alternatives. On the other hand, the two decentralized alternatives give management four reports that are not provided by the centralized system. The centralized system has some additional advantage in that some of its reports are prepared daily. The other two systems require more time in the preparation of reports. Over all, there is a net advantage of two reports with the centralized system.

The savings of $7500 a month for the centralized system noted in Table 4.5 are estimates for the time when the inventory is put on the machine. Since the estimates were rough and the time for converting the inventory was indefinite, no specific discounting factors were used. The consultants originally drafted a report that showed equal savings for a system using a computer and a system that was basically a revision of the company’s current practices with the addition of electronic equipment. When it was pointed out to the consultants that a recommendation was expected from them, the additional savings from converting inventory were added and the centralized system was recommended.

The implication of the foregoing should not be that cost and savings estimates were unimportant. During the six months of the consultants’ investigations, cost estimates played a prominent role in the analysis. For example, time and motion studies were made to derive time estimates, and the resulting estimates were closely scrutinized. Some time estimates were revised as many as three times. In the meeting of the management committee where the formal decision was made, the questions pertained primarily to costs. There was concern for the break-even point of the investment and the pay-back period.

Despite their explicit importance, however, costs entered into the decision in a way somewhat different from that anticipated by traditional theory. As in the previous cases, the first question apparently asked was whether the computer installation or the other new installations studied would be economically feasible. The original report of the consultants as well as the analysis by management indicated that two of the three systems studied were feasible and preferable to the existing system. Given this basic conclusion, the use of cost data and the attitude toward that data became much more flexible than they probably would have been otherwise. Since two of the systems were defensible as replacements for the existing system, the choice between them seems to have depended less on an objective effort to assign meaningful values to intangible or uncertain advantages than on important individual preferences. Thus the controller was interested in a system that produced more information faster and with better control. He, and others, felt that the computer might become an important general managerial tool. Although they obviously felt the necessity of justifying the installation on comparative cost-savings grounds, their attitude toward the hypothetical savings of $7500 was undoubtedly generous. Their attitude would have been different had they not been favorably inclined toward a computer nor persuaded that straightforward, tangible benefits made the centralized system an “acceptable” solution.

In addition, the relation between the consulting firm and the organization points up some interesting features of the role of expectations. In this case, the organization relied on an outside source for information, but some of the behavior of the ambiguous situation in the third case also occurred here. The consultants made a detailed, careful, and responsible analysis of the proposed installations. Nevertheless, when asked to make a specific recommendation, they were able to change the summary figures on cost savings from a set that indicated indifference between two major alternatives to a set that indicated the clear superiority of the computer. The point is not that the consultants falsified their data. They clearly would have refused to do this, and the organization would not have countenanced it. However, they had to make a judgment as to which uncertain costs and savings should be counted, and this judgment was almost certainly affected, as had been the earlier judgments of staff members within the organization, by their perception of management’s attitudes and predilections.

In each of these case studies we have seen the interaction among the problem situation, the data collected, and the expectations formed. In addition, in at least three of the cases, information gathering is clearly decentralized. Special subunits gather information and provide it to other parts of the organization. Thus, before attempting to examine the implications of these studies, we need to consider the special features of information transmission within a decision system in which conflict is only partially resolved.

Source: Skyttner Lars (2006), General Systems Theory: Problems, Perspectives, Practice, Wspc, 2nd Edition.