The importance of the macro-political developments and their likely effect on the futures of power in organizations is that the futures of power will be largely depen- dent on the magnitude of the changes that are affecting and will affect the orga- nizational world over the next few decades. In this book we have constantly put forward the socio-historical dimension of the genesis and of the dynamics of power as a concept and as a sociological and political condition of everybody’s life in contemporary organizations. Put differently, whether the agenda for change will be minimalist, redistributive, developmental or even structuralist, to take March and Olsen’s four (1995) conceptions of the political agenda at the level of societies, the nature and culture of power will be durably affected. Minimalist power is rela- tively indifferent to substantive outcomes and the construction of identities; it is more used to minimize the costs of political battles. Redistributive power is used to limit inequalities in both the polity and the power of the elite. Developmental power is used to generate shared cultures and educate the people in so far as it con- stitutes a political community. Structural power is used in the engineering of spe- cific institutions aiming to shape and control the demands of the polity (1995: 242–5). In Table 13.1 we sketch what this might imply for the concept and use of power.

Power is likely to be increasingly institutionalized in the organizational world as the futures of power in organizations revolve around two major issues:

Table 13.1 A framework with which to think about the institutional futures of power

- How will organizations preserve and enhance individual freedom and initiative while relentlessly engineering new managerial institutions that strengthen narrow circles of powerful individuals monitoring the organization from the top? How will they combine a structural and a minimalist agenda?

- How are organizational leaders going to embody the growing societal and polit-ical dimensions of their activity? Put differently, the transformation of leader- ship from a set of managerial practices and rules to a set of institutional capacities implies that we think about power in organizations as a means to edu- cate, to socialize individuals, to create and sustain identities – and to consider the role of elites as governing institutions instead of merely managing organizations.

We can also draw from the works of four major figures of this book, Weber, Simmel, Durkheim, and Foucault, not only to highlight different perspectives, which has already been done in the previous chapters, but to envisage a possible combination of their views to think through the conceptual futures of power, as shown in Table 13.2. Given the stakes of the present period and the analysis that we have made of them, it goes without saying that we argue that organization studies should not merely shift from an efficiency-oriented perspective to one that is explicitly politically oriented. To comply with a managerial directive is to accede to a moral or political agenda that one does not necessarily share. The role of political power is to invent and engineer powerful institutions that create the necessary obedience-generative constraints and legitimacies inside organizations and societies. One of the most pressing questions posed by a perspective based on a political agenda is that of moral disagreement. The dispersion of individuals and values around the globe in the present context of global ‘organizational sprawling’ emphasizes the discrepancies between decisions made in some circles of power and the perceptions and interpretations of individuals; put another way, the question of how to manage the common affairs of people who dis- agree about moral and non-moral matters but live together in the same society/orga- nization should be stressed. The urgent research question posed by the current growingly important ‘social agenda’ of organizations involves a series of topics. What will be the ways of binding the changing political commitment of individuals to new demands of power and of political communities in organizations that both colonize an increasing amount of their lifeworld and offer a diminishing sense of security? What will be the power of moral ‘things’ in the design of political structures and in the production of political leaders for organizations in the future? What will be the new balance between directive and soft power? How will organizations act as increas- ingly political subjects in a world where the changing relations between states and markets increasingly empower non-state actors and disempower individual con- sumers bewildered by the confusions of alleged choice?

1. Resistance, political apathy, and transfers of power

One can agree with the idea that the traditional elements of the old European order, resting on kinship, social class, religion, local communities, monarchy (Nisbet 1993), were scrambled by the forces of democracy. No longer as sharp and clear, they form an omelet; in some countries the monarchy has been removed from the mix, in others the church has been separated from the state, and so on. Traditions live on in some places like a nightmare in the brain of the living, as Marx once put it. One might think of the noble titles, for instance, which decorate the boards of business organizations. But they are tangled up in new circuits of celebrity, where porn stars are indistinguishable from heiresses and heiresses from porn stars, where celebrity is an end in itself, where people are famous for being famous.

Table 13.2 The conceptual futures of power

The ideological signification of democracy in the organizational world is not only related to a kind of moral utterance. It is also the work of power, since democ- racy in economic institutions is antagonistic to oligarchic and bureaucratic prac- tices and values. It is not only power in the mechanical sense of ‘force applied to a people by external government in the pursuit of its own objectives, but power regarded as arising from the people, transmitted by libertarian, egalitarian and rationalist ends so that it becomes, in effect, not power but only the exercise of the people’s own will’ (Nisbet 1993: 40). The question arising from this quotation concerns not merely how far organizations can be truly democratic but the pecu- liar interconnections between democracy, power and morality. As Nisbet (1993) puts it, power without morality is despotism, while morality without power is sterile. Scholars must therefore think through the combination of democracy, power and morality. So far, we have barely begun to do this in the contemporary practices of organizations. How can we reconcile the parameters of a Habermasian ideal speech situation as the form of democracy that respects the humanity of people with the functional necessities of divided, specialized labor and centralized administration? Can the political imagination usher in changes correlative with the new distributed forms of technology that are now available? The pen and the typewriter gave us bureaucracy; can virtuality give us democracy?

We think that future regimes of power will be deeply characterized by their capacity to build credible combinations between these three elements. This is why we consider resistance as an outdated topic in the study of power. The tensions and competition between different combinations of identity are much more interesting than the never-ending description of the always possible or potential resistance of actors, imagined as if they were puppets waiting the old scripts of solidarity to ani- mate them, forever cast in their workerist identities. Today, the solidarities are more likely to be ethically nationalistic or religiously fundamental or both, and the con- sequences not so much liberatory but terrible. If nineteenth- and twentieth- century organizations might have had many occasions to fear their employees qua workers – because of the power of organized labor – the twenty-first century has more to fear from the anonymous terrorist or the barely recognized ethnic and reli- gious tensions that simmer in their remote branch plant’s or supply chain’s hinter- land, brought into the organization by those whom they employ or subcontract.

Contemporary conditions of political action in organizations lead us not so much to consider questions of solidaristic consciousness as to emphasize the ques- tion of transfers of power. What is relevant is to study pivotal moments in the life of organizations and individuals, dates that are durably resilient in organizations’ and individuals’ memories. For instance, power scholars could be inspired by stud- ies on regime changes (Linz 1978) to identify the existence of common patterns in the process leading to changes in political structures, not only in states but also in organizations more generally. Studying the prerequisites for political stability is an all the more important topic in so far as, today, we are experiencing a brutal shift from postwar optimism about the durability of democratic regimes to a more pragmatic and short-term regional perspective on political stability. We do not mean that the period of coup d’état is vanishing in states, as the emergence of democratic or quasi-democratic regimes becomes more and more pervasive. In the past, such regime changes have been at the center of political analysis.

As far as organizations are concerned, the study of radical changes of the social and political structure is unlikely to shape the core of the power agenda for orga- nizational analysts, in terms of the macro-impact of state change. However, in terms of the more immediate effects of often hostile takeovers within commercial organizations, when we see the violent end of top management team careers associ- ated with particular organizations, there is great scope for research. Contemporary violence is no longer essentially political but is shifting to the realm of interpersonal and hierarchical relations, especially as they are contingent on stock-market raids and coups.

Within organizations, it is particularly interesting to decipher the signification of the supposed increase in psychological and moral forms of harassment as con- temporary figures of obtrusive forms of oppression. The question is whether the threshold of tolerance (the ‘zone of indifference’) for direct oppressive forms of power is decreasing, while the threshold of tolerance for remote, implicit and soft forms of power and domination is increasing. From this perspective political apathy implies that the perception of political violence in contemporary organiza- tions would be founded on a shared acceptance of the social division existing between elites and non-elites. As Michels (1962) prophesied, the fate of organiza- tions is largely dependent on the fragmentation between competent governors and those who are pragmatically and obediently governed. Such a political division of work implies that the governors establish new forms of control and surveillance on a more and more remote and indifferent polity. That is where the combination between soft forms of power and the political centralization of organizations is worth studying, for instance through the emergence of ‘soft bureaucracies’ (Courpasson 2000). Power will be shaped in the complex intricacies between the ‘absence’ of readable power mechanisms (the soft part of the structure) and the constant ‘pres- ence’ of the organizational machinery (its instruments, ratios and overwhelming ‘pressure-generating’ systems of control).

When a member of an organization faces a novel and morally charged situation s/he does more than merely apply a formulaic model or process, the organizational machinery, in order to decide on a course of action. In practice there will always be room for interpretation as various ethical models and calculations are used in rela- tion to the activities of organizing and managing. Thus, organizational members have to make choices to apply, interpret and make sense of various competing models of practice (including ethical ones) in specific situations. Such ethical work does not suggest a total ‘free play’ but implies that moral choice proposes an oscil- lation between possibilities, where these possibilities are determined situationally (Derrida 1988). Ethics are at stake when norms, rules or systems of ethics clash, and no third meta-rule can be applied to resolve the dilemma. We cannot avoid being moral beings that make choices ‘with the knowledge (or at least a suspicion in case efforts are made to suppress or deny that knowledge) that they are but choices. Society engraves the pattern of ethics upon the raw and pliable stuff of morality. Ethics is a social product because morality is not’ (Bauman, in Bauman and Tester 2001: 45). And if ethics cannot be articulated, it is invariably because power arbi- trates on, overrules, and otherwise struggles to fix meanings.

Ethical codes, norms and models have important implications for organizational members. They are resources that skilful and knowledgeable members use freely in everyday management. As Foucault suggests, ‘what is ethics, if not the practice of freedom, the conscious practice of freedom?’ (1997: 284). The moral agent, from a power perspective, is one who enacts agency rather than one whose actions are considered to be wholly determined structurally (see Lukes 1974; 2005). One may agree or disagree with particular ethical dictates, but it is what one does in relation to them that determines the practice of ethics.

A concrete example, at the heart of debates about power, and one that we have addressed earlier, makes the point clearly. Despite sustained claims regarding the unjust treatment of women in the workforce, and their relative lack of access to relations that are powerful, equal employment opportunity (EEO) legislation has not been sufficient to gain women equal status in organizations (Blackburn et al. 2000). A simplistic view would suggest that this should not have been the case; the rules should be implemented and complied with so as to produce the desired effects, including the realization of a more ethical and just state of affairs. In prac- tice, discrimination remains enacted through the tacit cultural micro-practices of everyday organizational life (see Martin and Meyerson 1998; Meyerson and Fletcher 2003). Such practices emerge from the relation between explicit EEO pronounce- ments, the enactment of gender in organizations, and the power and agency of those many people who interact in order to produce gender inequality.

When formal systems of ethics such as codes of conduct are present, following Meyer and Rowan (1977), they can be expected to function as ceremonially adopted myths used to gain legitimacy, resources, and stability, and to enhance sur- vival prospects. The practice of the system far exceeds its explicit statements. Thus, to maintain ceremonial conformity, ‘organizations that reflect institutional rules tend to buffer their formal structures from the uncertainties of technical activities by becoming loosely coupled, building gaps between their formal structures and actual work activities’ (1977: 340). In their search for legitimacy, organizations use codes of conduct as standards to justify what they do (Brunsson et al. 2000) as well as to fulfill a narcissistic obsession with looking ‘good’ (Roberts 2003). In this sense, codes of conduct become a ‘public relations exercise’ (Munro 1992: 98). Goffman (1961: 30) had their meaning nailed when he wrote about the partial reversal of transformation rules in encounters where ‘minor courtesies’ are displayed to ‘women and children in our society’ by men, honoring the youngest or weakest ‘as a ceremonial reversal of ordinary practice’. The point he makes is that codes of con- duct are not constructed out of a sense of esteeming and identifying with another who is like you but are instead an impersonal and productive convenience to secure selfish aims.

Take the example of Enron, a company that won prizes for its ‘ethics program’, a program designed more for impression management than ethical thoughtfulness (Sims and Brinkmann 2003). Such impression management practices might con- tribute to organizational legitimacy (Suchmann 1995) but not necessarily to the form of deliberation, decision, and exercise of freedom that characterizes ethically charged organizational problems. Should we analyze organizations in terms of what they say they do in their formal documentation or should we study what they actually do? Clearly, we should do both, while acknowledging that rhetoric has its own practice and it is the relations between the practices, the situations in which they occur, and the audiences they invite, that are important (Corbett and Connors 1999; Cheney et al. 2004; Suddaby and Greenwood 2005).

What needs to be investigated is how people adhere to, violate, ignore or cre- atively interpret formally ethical precepts. Organizational members engage with such formulations as a potential instrument of power that can be used to legitimize and delegitimize standpoints in power relations. As we saw in Chapter 6, with the cases of the total institutions, compliance can lead to ethically questionable out- comes. If there were guarantees of the ethics produced by following rules then the Eichmann defense would not have the notoriety that it has (Arendt 1994). Therefore, interpreting and adapting rules and maxims according to local circumstances, including sometimes even contravening them, might be deemed ethically sound. Rules are resources to legitimize and to negotiate organizational realities and their application will always be an occurrence of power/knowledge relations. Different versions of these generate conflicting visions of society.

2. Conflicting visions of society: the emergence of internal ‘social movements’?

Organization theory in the broadest sense of the term is very well suited to construct a convincing political theory of contemporary corporations. Actually, an extensive body of literature for decades has been analyzing the conditions of embeddedness of organizational politics in the social structure of corporations (Useem 1984; Ocasio 1994; Gouldner 1956). In Chapter 12 we stressed that the corporate elite is neither as parochial nor as fragmented as pluralist theories suppose, nor is it as unified and cohesive as elitist theories suppose (Davis and Thompson 1994). Rather, a social movement perspective can help to better grasp the current and forthcoming dynamics of power generation and maintenance in organizations. The existence of conflicting visions of organizations and society is likely to be the cornerstone of many studies of organizational dynamics, as current events suggest that collective forms of action and mobilization do not derive from a simple calculus of incentive, but rather depend on a number of uncertain and always questionable organized alliances and coalitions between actors.

Once again, we argue here that one of the most prominent questions for power scholars will continue to be that of who comes to dominate power relations. The main approach to this never-ending issue has, for a long time, been an exchange-based perspective (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). Based on a presumption of managerial control, internal power struggles, conditioned by specific environmental factors, determine who controls the resources that bestow the power to govern. Yet, one cannot assume that managerial control is still the rule.

Class-based perspectives (Zeitlin 1974), premised on a view of corporate owners and managers living in a relative harmony of interests, do not say much about the effects on this harmony of recent hostile takeovers, of the corporate upheavals of the 1980s, and of the subsequent political maneuverings by corporate managers, let alone are able to address the irruption of the pre-modern world in the post- modern society. Drawing from social movement analysis may enable one to inter- pret which processes and which common values future collective actors are likely to design as the political face of organizations. How actors translate shared inter- ests into common values is at the heart of current stakes in organizations (Tilly 1978). One of the most germane insights of these studies is that collective mobilization does not derive mostly from a certain level of grievances; an effective social organization among actors is more explicative of potential social movements and organizational turmoil than a given level of incentive, as Mann’s (1986) notion of organizational outflanking recommends. One fascinating issue would be to analyze how far current social agendas for organizational leaders (corporate social responsibility and sus- tainability issues, in particular) will challenge the actual decision-making processes and power distribution, by including new experts in the political process of decision making, and by enhancing the rise of unexpected challengers whose interests are not presently considered in the political structure.

How far do incumbent leaders have an interest in bringing morality back into business discourses and practices, and what risk do they take in doing so of facili- tating the emergence of new collective actors? The underlying question is that of the dynamics of corporate elites as a genuinely efficient social movement. If we accept the framework of Tilly (1978), pertaining to the politics of control, we can infer that, with regard to:

- Group interests, numerous studies suggest that corporate elites act as a relatively cohesive network through permanent interactions. Interlocks, for instance, can serve as platforms for social action.

- Social infrastructure, numerous studies, not least those of Bourdieu, remark that the degree of common identities and social backgrounds linking corporate elite members remains high.

- Mobilization, the ‘process by which a group acquires collective control over resources needed for collective action’ (Davis and Thompson 1994: 156), seems to be a relational skill that is still frequently exercised. Most corporate upheavals and changes are a demonstration of the capacity of corporate elites to gather individuals, skills, expertise and money to achieve a given purpose.

- Political opportunity structure, the probability of successful political ‘insurgen-cies’ (McAdam 1982), continues to arise out of periods of instability and incumbent elites’ challenges.

If we analyze political action as a combination of these four components, we suggest it might be of utmost interest to investigate the potential dynamics encom- passed in two contemporary phenomena:

- The current changes of corporate elite (see Chapter 12), as for instance the way internal competition between would-be leaders diminishes the chances of elites acting as a true ‘ruling class’ or, put differently, how the cut-throat struggles for scarce positions of power affect elite and subelite cohesion.

- The current emergence of new corporate professional actors, such as new types of professions (project managers, business unit managers, the profession of middle management as a whole). Here the investigation could focus on how power structures might be endangered and modified by a collegial type of col- lective action enhanced by the generation of a kind of ‘insurgent consciousness’ within the professional niches of the corporation (McAdam 1982: 49).

It remains an open question as to whether potential new political actors might influence structural power (i.e. the rules of the game), or ‘only’ wrest open redis- tributive and minimalist forms of power. We put forward the hypothesis that the future power structures of organizations will be largely shaped by the capacity of ruling corporate elites to rejuvenate the pillars of their legitimacy, and by the simul- taneous capacity of professional subelites both to be allegiant and to influence the governance of departmental and local subunits. These subelites might act as ‘orga- nizational activists’ so to speak, working to engineer a new structural differentia- tion between the center and the periphery.

3. The specter of ‘ lost power’

As Tocqueville put it a long time ago:

In our days, men see that the constituted powers are crumbling down on every side; they see all ancient authority dying out, all ancient barriers tottering to their fall, and the judgment of the wisest is troubled at the sight … If they look at the final conse- quences of this revolution, their fears would perhaps assume a different shape. For myself, I confess that I put no trust in the spirit of freedom which appears to animate my contemporaries. I see well enough that the nations of this age are turbulent, but I do not clearly perceive that they are liberal; and I fear lest, at the close of those perturba- tions, which rock the base of thrones, the dominion of sovereigns may prove more powerful than it was ever. (1945: 314)

A similar statement could have been uttered by any analyst of our days. We have argued on numerous occasions in this book that new types of power, more encom- passing and penetrating than ever before in history, are emerging out of the ashes of modern institutions. Power will be less and less submerged in the ethos of well- delineated communities, where the power of the elite could seem to the governed little different from the power exercised by familiar and sometimes reassuring figures such as the father, the priest, or the master. Power is no longer an ‘undifferentiated aspect of the social order’ (Nisbet 1993: 108). The fragmentation and terror of the risk society as the essence of the postmodern condition are only the most heightened aspects of this state of affairs.

Nisbet explains compellingly that when individuals become separated from institutions, ‘there arises … the specter of lost authority’ (1993: 108). One might hypothesize that, in the organizational realm, given the ceaseless fragmentation and individualization of the social body, what is likely is a form of disintegration of the idea of power and, in parallel, a magnification of political power vested (nev- ertheless) precariously in remote and uncontrollable entities and principles (ethics, the environment, the pension funds, etc.). The increasing looseness of most insti- tutions in our times, and the diffusion of a ‘culture of precariousness’ amidst the state of insecurity, seem to require a growing concentration of political action, aimed at withstanding the current dislocation of the social foundations of organi- zations by all the shock troops of the global world, including for instance not only jihad but also fierce competitiveness as new arenas, such as China and India, enter the global scene, as well as increasing insecurity about the impact of the ecology on organizational action and of organizational action on the ecology.

We need to remember the seminal distinction between social authority and polit- ical power, the realm of rationality and centralization. Today’s organizations are characterized by the fact that power is, so to speak, not fused in the wider society. Deference is no longer shown to or expected by elders and betters. Organizations cannot simply rely on staffing their command with high-status males and expecting the subaltern ranks to obey unquestioningly. The social order is no longer mediated by clear-cut figures and organizational institutions supporting masculinity, author- ity, or religious or ethnic supremacy. It is wavering from one individual to another, from endogenous actors and groups to external constraints, and thus power is not generating individual security and beliefs in the relative unity of organizations as centers of power. Simultaneously, while the idea of power is dislocated, organiza- tions relentlessly produce alternative managerial instrumentations of, and discourses about, performance, that play the role of political devices of control, mediating the invisible power of the invisible center, reshaping the body politic. Following Tocqueville once again, the contemporary evolution of power can be sketched as moving from a situation where the power of a small number of persons prevailed to one where there is the ‘weakness of the whole community’, which now is being superseded by the antagonistic powers of dispersed and fragmented communities. Order in organizations, as our forebears knew it, even as late as the 1970s and 1980s, can no longer rely on the multiplier effect of an ordered society where ethnicities, genders, age cohorts, and classes knew – and kept – their place. All the past’s seeming social solidity has melted into air, and where once there was the illusion of an order that few questioned, now we can see only the effects of repressive tolerance; as long as the elites were mimicked, obeyed and reproduced in the masses’ behavior they would be tolerated. Acceptance was contingent on obedience.

There have been attempts by leaders, elites and others positioned as celebrities in the media circuits of power to remake a center that can hold, such as G8 and Live8. The current endeavor of organizational leaders and their delegates to seize upon ethical and environmental topics can be interpreted as an attempt to combine political and moral power in a single figure. Put differently, if the idea of power is dislocating, it is doing so in a period particularly suited for fusing into a single institution (the business corporation) the two faces of power: the rational and cen- tralized, the power-generating performance; and the traditional and diffuse, the power-generating legitimacy, and normative obedience. The joint dynamic of the two forces is all the more interesting and striking in that it contradicts the dynam- ics Weber foresaw, namely the antagonism between the moral objective of democ- racy, rule by the people, and the rational side of this objective, bureaucracy.

Behind the endless discourses on corporate social responsibility, one can see the politicization of moral values providing power with a new consistency, which was proposed by Durkheim. Power is moral life, because it is through ‘the practice of moral values we develop the capacity to govern’ (Durkheim 1961: 46). But power is also plural, by definition, according to Durkheim; it is manifested in the diverse spheres of social life, communities, webs of kinship, professions, school, unions, etc. Organizations endeavor to restore the consistency of a powerful social group, by gripping more firmly the individuals, by generating constantly new reasons to bind them to the corporate future, to make them believe they act for the sake of a socially useful and fruitful entity, to give a greater significance to individual actions, as Durkheim put it. Of course, twentieth-century neo-Durkheimians, such as Mayo, were well aware of this function of organic solidarity, a form of corpo- ratism writ small.

Durkheim expected anomie where the social bonds did not cohere. In the nine-teenth century anomic suicide was the favored escape attempt. One might interpret today’s striking consumption of soft drugs in the workplace as the twenty-first century’s substitute for suicide. The causes are partly the same: social atomization, moral emptiness, uncertainty and the specter of ‘lost power’. The combined dynamics of the political and moral sides of the business and organizational realm might be likely to supply the ‘social substance’ now lacking in fragmented individ- ual lives. As Nisbet puts it wittily, ‘new forms of social organization must be devised to escape the contradiction involved presently in a horde of individuals whose lives are regulated but not really ruled by the distant, remote, and impersonal state’ (1993: 156). Business corporations, because they are de facto intrusive, must be potent, to avoid the Durkheimian prophecy of governance:

[I]nflated and hypertrophied in order to obtain a firm enough grip upon individuals, but without succeeding, the latter, without mutual relationships, tumble over one another like so many liquid molecules, encountering no central energy to retain, fix and organize (1951: 389)

The possible peculiarity of present times is that, as we suggested earlier through the idea of ‘organizational activism’, the overwhelming hypertrophy of the business world in today’s societies does not necessarily go hand in hand with the atrophy of other identity-generative kinds of social groups. The current moral wave might be carrying the promises of a joint development. But still, it is out of the agonistic tensions between these forces that a new consistent social order will arise.

4. From subordination to new forms of oppression?

The question posed by the current plethora of political discourse about the environment, society, sustainability, and responsibility might resemble the kind of emerging political identities that Laclau and Mouffe identified in their landmark Hegemony and socialist strategy (1985). We suggest that the current period might be favorable to the emergence of new social movements from the post-Enlightenment space, championing issues of environment, ethics, and even, to some extent, a return-to-simple-life discourse and values.27 Such movements are intriguing for several reasons.

The political identities emerging from this movement are far from being clear; nobody really knows who are the active behind-the-scene ‘messengers’ and what are the political struggles and coalitions maneuvering to bring these ideas to the front of the scene. A fuzzy community of politicians, humanitarian activists, jour- nalists, intellectuals, and so on has generated a common agenda to which corporate leaders have more or less recently turned to legitimate new sources of performance. We think that the type of ‘democratic revolution’, using Tocqueville’s expres- sion, which is represented by these new mass forms of mobilization around specific issues, is likely to produce a slight shift in the name of a newly designed common good, that of the planet and other generalities. In this sphere it is the non- governmental organizations, such as Greenpeace and World Vision, moral organi- zations staffed by moral actors, which are decisive. Organizational leaders have already seized upon some of the arguments emanating from these organizations to help them turn some new tricks in their repertoire of corporate discourse, such as the ‘triple bottom line’.

One could draw from Laclau’s idea that all hegemonically constructed order entails ‘ethical investments’; ‘hegemony entails the unending interplay of “contin- gent decisions” between the “ethical” (“ought”) and the “normative” (“is”)’ (Townshend 2004: 277). Current attempts to construct a new democratic and eth- ical order, which occur in nearly every business discourse or media utterance con- cerning business, can be analyzed as democratic attempts constituting ‘the only form of hegemony that permanently shows the contingency of its own founda- tions’ (Laclau 1990: 86, quoted by Townshend 2004: 277). It remains to be seen how far these pro-democratic and pro-ethics movements are anti-capitalist – and thus true to their origins. What is relatively clear is that the debate is located not inside the capitalist world and the organizational realm, but on its fringe. At the same time what is particularly striking is that organizations, while seizing upon the soci- etal political discourse, do not allow the formation of other types of forces likely to become other hegemonies, without striving to control them. In particular, this is the case with ethical movements, as they pertain to one of the major pillars of the organizational political structure. The legitimacy of corporate elites, and specifi- cally that of their right to act in the name of a common good which is supposed to be a common will, is exemplified by Bill Gates appearing with Bono and Bob Geldof on stage at Live8. Adorned with new ‘ethical outfits’, the corporate elite is prone to build a new discourse of performance that is all the more decisive as it concerns making organizations true political subjects.

5. Extending organization power

Power was always a reciprocal matter – not only of its relations and its exercise but also of its anticipation and normative shaping on the part of those subject to it. Today it is a much more instrumentally mediated relationship than one of face- to-face imperative coordination. If the calculus of power continues to be the model for face-to-face organization, and immediate imperative coordination, then power will increasingly seem to be missing in action. Yet, its traces are more pervasive the more mediated they become, and the more the mediations enchant, charm and captivate us; as we have been at pains to argue, seduction may be sensual but is still a form of power. The aspirants to the corporate elites in thrall to their BlackBerries are as mediated in being effects of power as is any lowly checkout worker moni- tored by the speed of her or his transactions. Of course, the one form of mediation is experienced more seductively and pleasurably than the other. Yet, in either case, the captive checkout operative in less than a square meter of space, or the executive globally roaming, both are held in mediated power relations.

One of the behind-the-scene ideas encompassed in the notion of ‘power disper-sion’ is that in the large and sprawling structures (physical and non-physical) of contemporary organizations, power operates (mostly) indirectly, without face- to-face interactions, in activity systems outside the boundaries of a face-to-face setting. As Goffman (1972) suggests, multisituated game-like activities, such as the ‘newspaper game’ or the ‘banking game’, involving occupational communities with motives and positions generated and realizable within the community, can also be analyzed in these terms.

Within the organizations that these games compose and recompose, according to contemporary consulting practice, hierarchies are supposed to flatten and the chains of command are constantly stretching out their tentacles further. While policies are elaborated by a small number of ‘informed’ power and knowledge holders, their implementation will be carried out by a number of people many levels below. Societal and organizational dynamics are possible because invisible and anonymous people act, react and incorporate their effects and aftermaths. Of course, organiza- tional theorists have long recognized and analyzed the way power extends through hierarchical systems; they have long written about ‘determinate hierarchy’ (Simon 1976: 22) or declared that ‘everyone must be subordinate to someone’ (Barnard 1938: 176). Today, nevertheless, the nature of this extension is different.

The ‘iconic’ dyadic approach to power relations long restricted organization the- orists to reciprocal intervention of A and B (Dahl 1957: 202–3; Lukes 1974: 34), as if a connection between the two was a necessary condition for any power relation; but what was left unspecified was how to analyze ‘power beyond adjacencies’, or ‘power at a distance’, to use Willer’s (2003: 97) expressions. Indeed, taking their cue from the community power debate many theorists would follow Dahl (1957) in insisting that there can be no power at a distance (see the discussion in Clegg 1989: Chapter 2).

We have argued in this book that the development of substructures of power is one of the most likely transformations of the political structures of organizations, if the latter are to extend and refine their democratic side. Strong power substructures are the condition of the development of democratic, polyarchic kinds of organizations. To know whether such arrangements are a desirable objective is another matter, a matter of judgment, of value. But the Weberian distinction between ‘feudal hierar- chies’ and what we have termed ‘polyarchic hierarchies’ still requires investigation, especially as to how internal ‘social movements’ are likely to emerge in polyarchic settings, and how far the extension of power relations facilitates or discourages the generation of strong endogenous substructures of power.

We should not forget those who are squeezed by flatter structures – the excluded, or at least diminished, middle. Middle managers occupy highly uncertain and threatening positions, which, while organizationally ‘superordinate’ in Simmelian terms, ‘are squeezed between high power superiors and a subordinate not weak- ened by exclusion’ (Willer 2003: 1324). One can imagine that the subleaders of political substructures will strive to develop alternative means for achieving their goals and imposing their views other than classical dyadic interaction, for instance by using parallel networks of influence, or gatekeeper’s positions. The current development of corporate professions through parallel ‘private–public’ personal endeavors by certain individuals might be seen as part of these attempts to generate power outside of the softly locked power circles of the organization.

Once again, the constant contemporary mobilization of ethical and envi- ronmental rhetoric is merely an extension of political ordering, seeking external arguments and faraway actors as determining, at least partially, the internal decision-making systems. New stakeholders have their uses. Furthermore, in the investigation of power at a distance, while it analyzes the effects of new political conditions on elite stability and legitimacy, it is highly likely that the extension of political webs will imply greater legitimacy from, and for, power holders; in that sense, the pillars of legitimacy, since they are no longer essentially founded on face- to-face interactions and ‘on the spot’ legitimization processes, are shifting to the complex combination outlined in Chapter 11 between meritocratic and hereditary aspects of elite stability. We summarize these reflections in Figure 13.1.

We have suggested in this book that, through the use of social movement theory, newly emerging dynamics entail that contestation is clearly considered as a possi- ble political action. The creation of strong substructures, as well as the mobiliza- tion of exogenous rhetorical opportunities, act as a trigger for collective action inside the organization. That is where the never-ending apparent contradiction between the hard power of contestation patterns and authoritarian settings (if we admit organizations are authoritarian settings, not in the sense of dictatorial and totalitarian regimes, but in the sense of non-democratic decision-making systems) and the soft power of governmental rationalities takes on a new sense.

6. Soft and hard power

The debate over the respective merits and mechanisms of hard and soft forms of power is centuries old. We find it behind the scenes in the fundamental opposition between Hobbesian and Machiavellian versions of politics as the struggle against adversaries, as the vision of sovereignty and the social construction of strategies are at the heart of these versions (see Clegg 1989). At first sight, in the sovereign version there is no need to struggle, as there are neither credible nor powerful enough adversaries; in the strategic version diverse ingredients have to be mobi- lized to vanquish mobile and hardly controllable adversaries. Put differently, soft and hard versions of power might well be the most structuring conceptual and empirical antagonism in the study and understanding of power.

Figure 13.1 New dynamics entailed by the extension of power relations

The debate has intensified recently, perhaps as a result of 9/11. The field of inter- national politics enables us better to grasp the futures of political dynamics in the organizational realm, because it has to deal with the same types of turmoil and political violence (notwithstanding the effects in terms of casualties). On one side, certain thinkers and politicians are constantly declaring soft power irrelevant, as the battle against enemies (of the US in this case) supposes that the only possible response to terror is to engage in coercive strategies, unleash overwhelming vio- lence in tactics of shock and awe, and not to attract and seduce individuals and groups (the terrorists) who, by definition, are repelled by the symbols and sover- eign power of America, and the Western world in general. On the other side, another fringe of political scientists, led by Joseph Nye in particular, in the US, claim that it is when hatred is at its peak that soft power should be used. The language of attraction and diplomacy should replace the language of coercion.

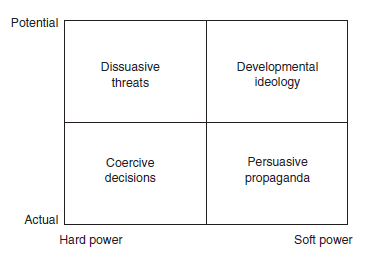

Soft power is the ability to get what you want by persuading others to adopt your goals. We are right in the middle of the Lukesian third dimension of power and those positive visions of power familiar from Follett, Luhmann, Parsons, Arendt, or Foucault, power that grows out of a political community and a political culture strong enough to avoid using force and coercion. We recall the old distinction, of which Aron (1972) reminds us, between actual power and potential power. The power of leaders derives from shrewd articulation between concrete actions (of power) and uncertain potentialities of exercising power. In Figure 13.2 we elabo- rate a grid with which to analyze the emergence of specific forms of power in orga- nizations. At the crossroads between a soft/hard and an actual/potential continuum of forms of power we suggest there are four major forms interacting to produce the actual mechanisms of power in organizations.

Figure 13.2 Four archetypes of power

In both archetypes founded on hard power, power holders are clearly definable. Actions and threats come from a specific and clear-cut source. One can assume that power holders know what they are doing when they decide (in a first-dimensional kind of approach) to use political resources to overcome resistance or to force alle- giance. In both archetypes founded on soft power, matters are blurred. The per- suasive propagandists believe they know what they are doing; they are composed of different sets of actors and instruments (media, technology, discourses) among which the inner circle is barely definable. The idea of developmental ideology is even more complex. It is a form of power defining the nature of exchange and promises, creating an implicit social pact between governors and governed. Moreover, it is a form of power implicitly shaping situations in which actors will be enshrined, in the name of a well-structured and well-defined common good (which, for instance, takes the shape of ethics and societal responsibility). From the common good it is supposed that allegiance will stem. But the common good can never be captured in a mode of domination, in a vision imposed on the others, in a claim based on any pretext of managerial fiat or real ownership over and above those of the managed and non-owning:

The ‘human essence’ lying forever in the future, the pool of human possibilities remaining forever unexhausted, and the future itself being unknown and unknowable, impossible to adumbrate (‘the absolute other’ in Levinas’ vocabulary). Such a view of human modality breathes tolerance, offers the benefit of the doubt, teaches modesty and self-restraint.

If you know exactly what the good society is like, any cruelty you commit in its name is justified and absolved. But we can be good to each other and abstain from cruelty only when we are unsure of our wisdom and admit a possibility of error. (Bauman, in Bauman and Tester 2001: 47)

The peculiarity of the developmental archetype that sees leaders leading those whom they dominate, however softly, however benevolently, is twofold. First, it assumes that there are no fundamental disagreements between leaders and led about the pathways to the future. Both sides of the political hierarchy share a sim- ilar awareness of the stakes and the hurdles to overcome in order to manage to build up a common future, ‘together’. A common pragmatism might lead to the disappearance of divergences, building a constrained political community in Arendt’s terms. Leaders do not exist on the fringes of the organization but are nec- essarily nested inside a community which is itself hierarchically structured. Second, this pragmatic common shaping of a political community does not mask the unawareness of both sides, leaders and led, of the underlying structure of power constructing, de facto, the conditions of political action.

The developmental ideology archetype is a way of combining and fusing the two major political dynamics that we have suggested characterize contemporary orga- nizations: the political community move, and the turn to organizational activism. Between these apparently opposite dynamics (one driving integration, the other driving resistance and fragmentation), new developmental forms of power are act- ing to fuse the subsequent effects of these dynamics. The supreme exercise of power would be to make organizational activists work for the establishment and main- tenance of a true political community, while being unaware that they are being used that way, and thus not really paying attention to it. Needless to say, as far as the fundamentalisms are concerned, the prospects for achieving this seem remote indeed.

7. Contestation in soft authoritarian organizations and value-based leadership

As we have already suggested earlier in the book, organizations are not an easy place to develop and implement democratic principles and practices. Organizations, and specifically business organizations, are among the least democratic institutions of modern times. Their attachment to hierarchy as an organizing principle is remark- able, as we have suggested. Such proclivities do not mean that most organizations are coercion-based regimes but assert that they are not designed to distribute power equally among members, that power holders are not elected by members, that cru- cial decisions will be made in small circles of power without necessarily seeking members’ opinions, and so forth. Even at their best they are oligarchies based, sometimes, on some notions of merit.

The question of contestation takes interesting shape if we view contemporary organizations as soft authoritarian systems (Courpasson 2006). Following Tilly (1978), we suggest that two general paths are likely to drive forms of contestation: political opportunity and threat. Opportunity will be defined as ‘the likelihood that challengers will enhance their interests or external existing benefits if they act collectively … threat denotes the probability that existing benefits will be taken away or new harms inflicted if challenging groups fail to act collectively’ (Almeida 2003: 347). The question of what might drive collective action within organiza- tional settings that are softly coercive invites several answers; for a start we would nominate a collective fear of losing rights and safety, such as holiday entitlements and safety and penalty clauses in workplace agreements; the expansion and exten- sion of new demands designed to preserve old powers, such as enhanced share options for senior management teams; and fear of the unanticipated consequences of those strategies of self-preservation that elites routinely enact, such as the infla- tion of book-based stock values in the here-and-now through systematic under- investment in the future. Of course, these are not just dysfunctions of private sector organizations; they are only too evident in government and public sector organi- zations, especially where they are wedded to the neoliberalism of new public sector management, and accounting mechanisms that insist on year-end balanced budgets. It is always easy to balance today’s budget if you do not spend for tomorrow’s needs. It is also highly irresponsible; today’s managers are custodians of tomorrow’s life chances. Where they manage as if they were Vikings, pillaging the future, they betray those whose inheritance they have created.

It is by no means sure that subgroups have a chance to enhance their interests and to gain advantage by acting collectively. If, as we contend, organizations are still based on strong central structures of power, the formation of challenging sub- structures requires important cognitive attributions, clearly defined shared inter- ests and organizational resources. For instance, the mobilization of specific internal networks will be required. As Almeida (2003) puts it, in any authoritarian and non- democratic environment, organizational infrastructures are necessary for any actor to link previously unconnected communities.

Following Tilly (1978), once again, three different forms of threat are likely to have an impact on power structures:

- Economic tensions, which can be attributed either to environmental factors or, more locally, to management causes rather than those that are generalized and generic.

- The erosion of the rights of organizational members, which means, in the organizational context, that the growing distance between individuals and decision-taking arenas makes people feel as if they are working in less trust- worthy environments.

- Organization repression and violence, action which might generate sufficiently significant moral shocks and collectively shared emotions to boost group protest activities (on the ‘too much is too much’ mode). The articulations of this with the perceived threats that emanate from the state of insecurity will be significant; the violence may come from either the state or private sector organizations.

We suggest a specific conjunction of these three elements is at hand in contempo- rary organizations. If the existence of fuzzily attributable economic difficulties is not sufficient to account for the emergence of contention and contestation, the conjunction of the erosion of rights and the sophistication of coercive methods in organizations (especially through new digital technologies of surveillance and the concertative discipline of teams) is likely to foster, within the organizational polity, new forms of protest and expression. The point is to decipher the reciprocal influ- ences of the public organizational and private spheres in framing individual decisions to contest. What is at issue here is the future of legitimacy.

8. The future of legitimacy

Many contemporary questions surround the future of legitimacy, but they are not the classic questions derived from the Marxist canon of collective consciousness challenging system legitimation (Habermas 1976). An example of the kind of con- temporary challenge to legitimacy is given by the massive emotional gatherings that occurred in France following the death of Pope John Paul II. While the exist- ing circles of elites (both political and intellectual) were discussing the legitimacy of flying the national flag at half-mast, thousands of people, particularly the young, were heading to Paris in specially chartered trains and coaches, while other gather- ings occurred in scattered places in France to share common meetings, create spon- taneous communities, and reflect on the significance of the event. Whatever one thinks the significance of these events to be, the point is that on this occasion, the elites had lost control of the people’s wills and preferences. And that is probably why these elites so harshly and somewhat uselessly focused their critique on the tri- color and the role of the state in that affair, as something whose separation seemed questioned by this undisciplining of civil society. A similar spectacle was observed at the funeral of Princess Diana (see Clegg 2000). A further example would be the defeat of the elite-sponsored referendum in favor of affirming the European con- stitution that occurred in France on May 27, 2005. The masses did not do as the elites would prefer.

Spectaculars may be the only means capable of mobilizing sufficient energy and social vibrations to foster collective social dynamics in future. The power of private emotions in the triggering of contest waves in organizations or in social and emo- tional collective action is a long way from the dyadic nature of power and micro- social approaches to power and obedience. As Satow (1975) has long suggested, completing the Weberian types of authority might prove more necessary than ever. If, as we have clearly argued, contestation might arise from unexpected events, the power of value-rational forms of social action à la Weber is worth exploring, to shed light on the still absent value-rational forms of leadership. To go back to the question of organizational social movements, we suggest one of the missing links between the ethical and environmental realms of legitimization and the subse- quent potential transformation of political structures resides in the absence of a coherent model of leadership. Following Willer, a value-based model of leadership would be founded on ‘faith in the absolute value of a rationalized set of norms’ (1967: 235). Obedience (of the governors as well as the governed) may be due to an ideology proffering legitimacy such that those in dominant relations of power derive their mandate directly from their exemplary relationship to the goals of that ideology.

The problem with the theory of the ideal type of legitimacy is that value-based leaders are expected to take decisions, regardless of the consequences of those deci- sions on the organization, from the moment when the decisions are ‘aligned’ with the goals of the ideology. It is naturally not the case in business organizations, except if we accept the hypothesis of the emergence of global corporate elites, taking decisions in remote circles of power, defending first and foremost the interests of the global cor- porate village, regardless of the consequences of these decisions on more parochial aspects and subleaders. An uncertain political regime, defending otherworldly objec- tives, but monitoring simultaneously the necessary adaptations of the concrete orga- nizations in order to survive, would emerge where such events occur.

Source: Clegg Stewart, Courpasson David, Phillips Nelson X. (2006), Power and Organizations, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1st edition.